Tropicália

Tropicália (Portuguese pronunciation: [tɾopiˈkaʎɐ, tɾɔpiˈkaljɐ]), also known as Tropicalismo ([tɾopikɐˈlizmu, tɾɔpikaˈ-]), was a Brazilian artistic movement that arose in the late 1960s and formally ended in 1968. Though music was its chief expression, the movement was not solely expressed so, as it enveloped other art forms such as film, theatre, and poetry. Tropicália was characterized by the amalgamation of Brazilian genres—notably the union of the popular and the avant-garde, as well as the melding of Brazilian tradition and foreign traditions and styles.[2]

| Tropicália | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | Musical

Art

|

| Cultural origins | Late 1960s, Southeast Region, Brazil |

| Derivative forms | MPB,[1] pós-tropicalismo |

| Other topics | |

The term Tropicália (Tropicalismo) has multiple connotations in that it played on images of Brazil being that of a "tropical paradise."[3] Tropicalia was presented as a "field for reflection on social history."[4] Today, Tropicália is chiefly associated with the musical faction of the movement, which merged Brazilian and African rhythms with British and American psychedelia and pop rock.

The movement was begun by a group of musicians from Bahia notably Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, Gal Costa, Tom Zé,and the poet-lyricist Torquato Neto. Later the group moved from Salvador (the capital of Bahia) to São Paulo where they met with collaborators Os Mutantes and Rogério Duprat among others. They went on to produce the 1968 album Tropicália: ou Panis et Circencis, which served as the movement's manifesto.

Tropicália was not only an expression in analyzing and manipulating culture but also a mode of political expression. The Tropicália movement came to fruition at a time when Brazil's military dictatorship and left wing ideas held distinct but prominent amounts of power simultaneously. The Tropicalists' rejection of both sides' version of nationalism (conservative patriotism and ineffectual bourgeois anti-imperialism) was met with criticism and harassment.[5]

The movement officially ended in 1968. However the dissolution of the collective birthed a new wave of soloists and groups identifying as “post-tropicalist”. The movement has inspired many artists nationally and internationally. Additionally Tropicalia continues to be a main feature in the original Bahian group and their fellows’ work.[2]

Background

A dominant principle of Tropicália was antropofagia, a type of cultural "cannibalism" that encouraged the conflation of disparate influences, out of which could be created something unique. The idea was originally put forth by poet Oswald de Andrade in his Manifesto Antropófago, published in 1928, and was developed further by the tropicalistas in the 1960s.[2]

While concrete poets were not an initial influence upon the group's works, the two groups, particularly Veloso, Gil, and Augusto de Campos, would go on to share an intellectual partnership in São Paulo. This partnership would help the Tropicalistas to form connections with other artists around the city, most notably Rogério Duprat.[2]

Helio Oiticica’s 1967 work “Tropicalia” shares its name and aesthetic with the movement. The movement also utilized Carmen Miranda, a Brazilian/Portuguese international star, who in Brazil had come to be viewed as inauthentic. The use of Carmen Miranda's image and motifs became synonymous with the movement. Veloso in particular would imitate the icons gestures and mannerisms during performances. This usage was intentionally done as a means to address the concept of "authenticity". Miranda was seen as presenting a caricature of what true Brazilian-ness was by Brazilians while international audiences saw her as a representative of Brazil and its culture. This dichotomy provided the means by which the Tropicalistas could address the concept of authenticity in such a fashion that it was striking to their audiences.[2]

Musical movement

The 1968 album Tropicália: ou Panis et Circencis is regarded as the musical manifesto of the Tropicália movement. Although it was a collaborative project, the main creative forces behind the album were Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil. The album experimented with unusual time signatures and unorthodox song structures, and also mixed tradition with innovation. Politically, the album expressed criticism of the coup d'état of 1964. Key artists of the movement include Os Mutantes, Gilberto Gil, Gal Costa and Caetano Veloso. According to Maya Jaggi, "Gil was partly inspired by Jorge Ben Jor, a Rio musician on the fringes of the movement, who mixed urban samba and bossa nova with rhythm and blues, soul and funk."[6]

The anarchistic, anti-authoritarian musical and lyrical expressions of the Tropicalistas soon made them a target of censorship and repression by the military junta that ruled Brazil in this period, as did the fact some of the collective, including Veloso and Gil, also actively participated in anti-government demonstrations. The Tropicalistas' passionate interest in the new wave of American and British psychedelic music of the period - most notably the work of The Beatles - also put them at odds with Marxist-influenced students on Brazil's left, whose aesthetic agenda was strongly nationalistic, and oriented towards 'traditional' Brazilian musical forms. This leftist faction vigorously rejected anything - especially Tropicalismo - which they perceived as being tainted by the corrupting influences of Western capitalist popular culture. The politico-artistic tensions between leftist students and the Tropicalistas reached a climax in September 1968, with Caetano Veloso's watershed performances at the third International Song Festival, held in the auditorium of Rio's Catholic University, where the audience not surprisingly included a large contingent of left-wing students.

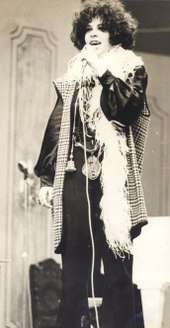

Veloso had won a major song prize at the previous year's Festival, when he was backed by an Argentinian rock band, and although his unconventional performance caused some initial consternation, he managed to win over the crowd and was feted as a new star of Brazilian popular music. By late 1968, however, Veloso was fully immersed in the Tropicalia experiment, and his performances, which were expressly intended as provocative art "happenings", caused a near-riot. In the first round of the competition on 12 September, Veloso was initially greeted by enthusiastic applause, but the mood quickly changed when the music started. Veloso came on dressed in a bright green plastic tunic, festooned with electrical wires and necklaces strung with animal teeth, and his backing band Os Mutantes were also dressed in similarly outlandish attire. The ensemble launched into a barrage of psychedelic music, played at high volume, and Veloso further outraged the students with his overtly sexual stage movements. The crowd reacted angrily, shouting abuse at the performers and booing loudly, and their fury was only exacerbated by the surprise appearance of an American pop singer, John Dandurand, who joined Veloso on stage and grunted incoherently into the microphone.

After such a powerful negative reaction, Veloso was unsure whether to appear in the second round on 15 September, but his manager convinced him to go on, and this chaotic performance was recorded live and later released as a single. The students in the audience began hissing as soon as Veloso's name was announced, even before he had even taken the stage. Wearing the same green costume (minus the wires and necklaces), Veloso came on with Os Mutantes amid a storm of catcalls, and the group launched into a provocative new song Veloso had written for the occasion, "É Proibido Proibir" ("It is Forbidden to Forbid"), the title of which he had taken from a photo of a Parisian protest poster, which he had seen reproduced in a local magazine. The booing and jeering was soon so loud that Veloso struggled to be heard over the din, and he again deliberately taunted the leftists with his sexualised stage actions. Within a short time the performers were being pelted with fruit, vegetables, eggs and a rain of paper balls, and a section of the audience expressed their disapproval by standing up and turning their backs to the performers, prompting Os Mutantes to respond in kind by turning their backs on the audience. Infuriated by the students' reaction, Veloso stopped singing and launched into a furious improvised monologue, haranguing the students for their behaviour and denouncing what he saw as their cultural conservatism. He was then joined by Gilberto Gil, who came on stage to show his support for Veloso, and as the tumult reached a crescendo, Veloso announced he was withdrawing from the competition, and after deliberately finishing the song out of tune, the Tropicalistas defiantly walked offstage, arm-in-arm.[3][7]

On December 27, 1968, Veloso and Gil were arrested and imprisoned by the military government over the political content of their work. After two months, the two were released and subsequently forced to seek exile in London, where they lived and resumed their musical careers until they were able to return to Brazil in 1972.

In 1993, Veloso and Gil released the album Tropicália 2, celebrating 25 years of the movement and commemorating their earlier musical experiments.[8]

Critiques

Tropicália's controversy can be traced to the uncertain and unfriendly relationship the members of the movement had with the mass media. The movement's emphasis on art clashed with the media's need for mass appeal and marketability. Tropicália additionally had an image of sensuality and flamboyance. This was a protest to the reinstated oppression of Brazil's military rule in the 1960s, and an additional cause for media pushback. In 1968, Tropicália events at clubs, music festivals, and television shows attracted media attention and aroused tension between Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil and their critics. This widespread attention attracted military attention and suspicion, who feared Tropicália's influence of protest in the cultural realm.

Near the end of 1968, Tropicália experienced a shift to a more overt association with international countercultures and movements, most notably that of African American Black Power in the United States. The movement was becoming increasingly leftist, and pushed for artistic output.[9] At a later Tropicália concert in the same year, during a performance by Caetano Veloso, a riot erupted in the auditorium between tropicalists and supporters of nationalist-participant music. The nationalists were primarily college students, and the uproar culminated with screams and hurling garbage at Veloso. The nationalist-participant group's resistance of the movement was nothing new, but this incident was the tipping point of their opposition. At the nightclub Sucata, Tropicália shows became increasingly resistant to Brazil's military-run society. Due to Veloso's refusal to censor the shows to government wishes, the military began to monitor Tropicália events. On December 27, 1968, at the peak of government repression, Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil were arrested, detained, and exiled to London for two and a half years.[2]

Modern critic Roberto Schwarz addresses Tropicália's hand in solidifying the idea of the absurd as a permanent evil of Brazil, and its issues with an ideological mentality. However, the approaches of the movement were ever-shifting and did not stick to one central idea.[10]

Influence

Throughout the 1940s until her death in 1955, the singer and actress Carmen Miranda made Hollywood musicals and performed live. Before first appearing on Broadway in 1939, she had a successful career in Brazil throughout the 1930s and was known as the "Queen of Samba." Yet after she gained international success in the United States, many Brazilians regarded her elaborate costume and performance as a caricature of Brazilian culture.[11] In Caetano Veloso's 1968 song "Tropicália," the musician references Carmen Miranda whose vulgar iconography were an inspiration. Caetano Veloso has said Carmen Miranda was a "culturally repulsive object" for his generation. Scholar Christopher Dunn says that by embracing Carmen, Veloso treats her as "an allegory of Brazilian culture and its reception abroad."[2]

Otherwise the singer Clara Nunes was more representative about real tropicalism that happened in Brazil. She made tour in Japan, Midem Festival (Cannes), Portugal, Germany.[12] Clara Nunes was a real brazilian syncretism woman artist in tropicalism era. Her songs was based in historical brazil, slavery, the ordinary life that was not simple but fill of complex detail that searching the beauty from of unknown. Clara Nunes, was a result of tropcalism moviment (1967 - 1969). Somehow post tropicalism helped create the social archetype to arise artists as Clara Nunes.

Many Tropicalistas have maintained a presence in Brazilian popular culture, specifically through MPB (Brazilian pop music). Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso are both respectively popular nationally and around the globe. Tom Zé, a Tropicalista who had largely faded into obscurity at the end of the movement, saw a resurgence of critical and commercial interest in the 1990s.[2]

Tropicalismo has been cited as an influence by rock musicians such as David Byrne, Beck, The Bird and the Bee, Arto Lindsay, Devendra Banhart, El Guincho, Of Montreal, and Nelly Furtado. In 1998, Beck released Mutations, the title of which is a tribute to Os Mutantes. Its hit single, "Tropicalia", reached number 21 on the Billboard Modern Rock singles chart.

Tropicália has morphed not only the Brazilian music scene itself but, the way Brazilian music is viewed. Tropicália expanded what Brazilians view as properly “authentic” and since the 90's broadened the way international audiences experienced and understood Brazilian music. Tropicália created a new precedent for artistic hybridization allowing for a diversity of sounds and styles in those who were inspired by the movement.[2]

Post Tropicália

Tropicalia introduced two very unusual movements to modern Brazil – antropofagia and concretism. In addition to this was pop music from abroad that helped inaugurate postmodernism in Brazil. In spite of the falling-outs and violence, there is a permanence of tradition in Oswald's antropofagia, who at one point of time conflicted with the idea of Romantic Indianism of the nineteenth century.[13] These ideas were and still are seen in theaters and people's notions that involved a relationship that tied back to a longer history of poetic creations.

Moreover, members of Tropicalia who were not arrested or tortured, voluntarily escaped into exile in order to get away from the strict and repressing authorities. Many continuously went back and forth between different countries and cities. Some were never able to settle down. People like Caetano, Gil, and Torquato Neto, spent time in places like London, New York, or Paris.[14] Some, but not all, were allowed to return to Brazil after years had passed. Others, still could only stay for short periods of time.

At the same time, underground magazines were expanding and this gave those who were overseas a chance to speak up about their experiences. Oiticica, for example, was one who moved to New York and published a magazine article titled, “Mario Montez, Tropicamp.”[15] The names for the titles that were used related to the risky and systematic aims during the times of Tropicalia. These magazines also told the stories of others who were in the United States and home in Brazil. By Tropicalia going underground, there was a unity of the members within the group because people like Oiticica sent these writing to Brazil so that the articles could circulate locally.

In 2002 Caetano Veloso published an account of the Tropicália movement, Tropical Truth: A Story of Music and Revolution in Brazil. The 1999 compilation Tropicália Essentials, featuring songs by Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso, Gal Costa, Tom Zé, and Os Mutantes, is an introduction to the style. Other compilations include The Tropicalia Style (1996), Tropicália 30 Anos (1997), Tropicalia: Millennium (1999), Tropicalia: Gold (2002), and Novo Millennium: Tropicalia (2005). Yet another compilation, Tropicalia: A Brazilian Revolution In Sound, was released to acclaim in 2006.[16]

A 2012 documentary film, Tropicália, was made on the subject and artists in general; directed by Brazilian filmmaker Marcelo Machado, where Fernando Meirelles served as one of its executive producers.[17]

Seminal albums

| Artist | Album | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Os Mutantes | Os Mutantes | 1968 |

| Various | Tropicália: ou Panis et Circencis | 1968 |

| Caetano Veloso | Caetano Veloso | 1968 |

| Gilberto Gil | Gilberto Gil | 1968 |

| Gal Costa | Gal Costa | 1969 |

See also

Further reading

- Paula, José Agrippino. "PanAmérica". 2001. Papagaio.

- McGowan, Chris and Pessanha, Ricardo. "The Brazilian Sound: Samba, Bossa Nova and the Popular Music of Brazil." Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998 ISBN 1-56639-545-3

- Dunn, Christopher. Brutality Garden: Tropicália and the Emergence of a Brazilian Counterculture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8078-4976-6

- (in Italian) Mei, Giancarlo. Canto Latino: Origine, Evoluzione e Protagonisti della Musica Popolare del Brasile. 2004. Stampa Alternativa-Nuovi Equilibri. Preface by Sergio Bardotti and postface by Milton Nascimento.

References

- Gildo De Stefano, Il popolo del samba. La vicenda e i protagonisti della storia della brazilian popular music, Préface by Chico Buarque de Holanda, Introduction by Gianni Minà, RAI Television Editions, Rome 2005, ISBN 8839713484

- "Tropicalia". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved November 7, 2015.

- Dunn, Christopher (October 15, 2001). Brutality Garden: Tropicalia and the Emergence of a Brazilian Counterculture. The University of North Carolina Press; 1st New edition edition (October 15, 2001). pp. 276. ISBN 0807849766.

- Veloso, Caetano, Barbara Einzig, and Isabel de Sena. 2003. Tropical truth: a story of music and revolution in Brazil.

- Perrone, Charles A. "Nationalism, Dissension, and Politics in Contemporary Brazilian Popular Music." Luso-Brazilian Review 39, no. 1 (2002): 65-78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3513834

- Perrone, Charles A. “Nationalism, Dissension, and Politics in Contemporary Brazilian Popular Music.” Luso-Brazilian Review 39.1 (2002): 65–78. Print.

- Jaggi, Maya (13 May 2006). "Blood on the Ground". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- Victoria Langland, "Il est Interdit d’Interdire: The Transnational Experience of 1968 in Brazil", Estudios Interdisciplinarios de América Latina y el Caribe, Vol. 17, No. 1 (2006)

- Béhague, Gerard, Gerard. (Spring–Summer 2006). "Rap, Reggae, Rock, or Samba: The Local and the Global in Brazilian Popular Music (1985–95)". Latin American Music Review. 27 (1): 79–90. doi:10.1353/lat.2006.0021.

- Harte, Colin (November 1, 2013). "Tropicália Film Review". Chasqui. 42 (2): 215–216.

- Béhague, Gerard (December 1980). "Brazilian Musical Values of the 1960s and 1970s: Popular Urban Music from Bossa Nova to Tropicalia". Popular Urban Music from Bossa Nova to Tropicalia. 14 (3): 437–452. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1980.1403_437.x.

- CARMEN MIRANDA: RIPE FOR IMITATION Indiana University

- Video Clara Nunes in Japan

- Brown, Timothy (2014). The Global Sixties in Sound and Vision. England: palgrave macmillan. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-137-37522-3.

- Harte, Colin (November 2013). "Tropicália". Chasqui: 215–216.

- Cruz, Max (September 2011). "TROPICAMP: PRE- and POST-TROPICLIA at Once: Some Contextual Notes on Hlio Oiticicas 1971 Text". Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry.

- Staff. "Tropicalia: A Brazilian Revolution In Sound". Metacritic. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1497880/