Troilus

Troilus[1] (English: /ˈtrɔɪləs/ or /ˈtroʊələs/; Ancient Greek: Τρωΐλος, romanized: Troïlos; Latin: Troilus) is a legendary character associated with the story of the Trojan War. The first surviving reference to him is in Homer's Iliad, which some scholars theorize was composed by bards and sung in the late 9th or 8th century BC.[2]

In Greek mythology, Troilus is a young Trojan prince, one of the sons of King Priam (or Apollo) and Hecuba. Prophecies link Troilus' fate to that of Troy and so he is ambushed and murdered by Achilles. Sophocles was one of the writers to tell this tale. It was also a popular theme among artists of the time. Ancient writers treated Troilus as the epitome of a dead child mourned by his parents. He was also regarded as a paragon of youthful male beauty.

In Western European medieval and Renaissance versions of the legend, Troilus is the youngest of Priam's five legitimate sons by Hecuba. Despite his youth he is one of the main Trojan war leaders. He dies in battle at Achilles' hands. In a popular addition to the story, originating in the 12th century, Troilus falls in love with Cressida, whose father Calchas has defected to the Greeks. Cressida pledges her love to Troilus but she soon switches her affections to the Greek hero Diomedes when sent to her father in a hostage exchange. Chaucer and Shakespeare are among the authors who wrote works telling the story of Troilus and Cressida. Within the medieval tradition, Troilus was regarded as a paragon of the faithful courtly lover and also of the virtuous pagan knight. Once the custom of courtly love had faded, his fate was regarded less sympathetically.

Little attention was paid to the character during the 18th and 19th centuries. However, Troilus has reappeared in 20th and 21st century retellings of the Trojan War by authors who have chosen elements from both the classical and medieval versions of his story.

The story in the ancient world

For the ancient Greeks, the tale of the Trojan War and the surrounding events appeared in its most definitive form in the Epic Cycle of eight narrative poems[3] from the archaic period in Greece (750 BC – 480 BC). The story of Troilus is one of a number of incidents that helped provide structure to a narrative that extended over several decades and 77 books from the beginning of the Cypria to the end of the Telegony. The character's death early in the war and the prophecies surrounding him demonstrated that all Trojan efforts to defend their home would be in vain. His symbolic significance is evidenced by linguistic analysis of his Greek name "Troilos". It can be interpreted as an elision of the names of Tros and Ilos, the legendary founders of Troy, as a diminutive or pet name "little Tros" or as an elision of Troië (Troy) and lyo (to destroy). These multiple possibilities emphasise the link between the fates of Troilus and of the city where he lived.[4] On another level, Troilus' fate can also be seen as foreshadowing the subsequent deaths of his murderer Achilles, and of his nephew Astyanax and sister Polyxena, who, like Troilus, die at the altar in at least some versions of their stories.[5]

Given this, it is unfortunate that the Cypria—the part of the Epic Cycle that covers the period of the Trojan War of Troilus' death—does not survive. Indeed, no complete narrative of his story remains from archaic times or the subsequent classical period (479–323 BC). Most of the literary sources from before the Hellenistic age (323–30 BC) that even referred to the character are lost or survive only in fragments or summary. The surviving ancient and medieval sources, whether literary or scholarly, contradict each other, and many do not tally with the form of the myth that scholars now believe to have existed in the archaic and classical periods.

Partially compensating for the missing texts are the physical artifacts that remain from the archaic and classical periods. The story of the circumstances around Troilus' death was a popular theme among pottery painters. (The Beazley Archive website lists 108 items of Attic pottery alone from the 6th to 4th centuries BC containing images of the character.[6]) Troilus also features on other works of art and decorated objects from those times. It is a common practice for those writing about the story of Troilus as it existed in ancient times to use both literary sources and artifacts to build up an understanding of what seems to have been the most standard form of the myth and its variants.[7] The brutality of this standard form of the myth is highlighted by commentators such as Alan Sommerstein, an expert on ancient Greek drama, who describes it as "horrific" and "[p]erhaps the most vicious of all the actions traditionally attributed to Achilles."[8]

The standard myth: the beautiful youth murdered

Troilus is an adolescent boy or ephebe, the son of Hecuba, queen of Troy. As he is so beautiful, Troilus is taken to be the son of the god Apollo. However, Hecuba's husband, King Priam, treats him as his own much-loved child.

A prophecy says that Troy will not fall if Troilus lives into adulthood. So the goddess Athena encourages the Greek warrior Achilles to seek him out early in the Trojan War. The youth is known to take great delight in his horses. Achilles ambushes him and his sister Polyxena when he has ridden with her for water from a well in the Thymbra – an area outside Troy where there is a temple of Apollo.

It is the fleeing Troilus whom swift-footed[9] Achilles catches, dragging him by the hair from his horse. The young prince takes refuge in the nearby temple. But the warrior follows him in, and beheads him at the altar before help can arrive. The murderer then mutilates the boy's body. The mourning of the Trojans at Troilus' death is great.

This sacrilege leads to Achilles’ own death, when Apollo avenges himself by helping Paris strike Achilles with the arrow that pierces his heel.

Ancient literary sources supporting the standard myth

Homer and the missing texts of the archaic and classical periods

The earliest surviving literary reference to Troilus is in Homer's Iliad, which formed one part of the Epic Cycle. It is believed that Troilus' name was not invented by Homer and that a version of his story was already in existence.[10] Late in the poem, Priam berates his surviving sons, and compares them unfavourably to their dead brothers including Trôïlon hippiocharmên.[11] The interpretation of hippiocharmên is controversial but the root hipp- implies a connection with horses. For the purpose of the version of the myth given above, the word has been taken as meaning "delighting in horses".[12] Sommerstein believes that Homer wishes to imply in this reference that Troilus was killed in battle, but argues that Priam's later description of Achilles as andros paidophonoio ("boy-slaying man")[13] indicates that Homer was aware of the story of Troilus as a murdered child; Sommerstein believes that Homer is playing here on the ambiguity of the root paido- meaning boy in both the sense of a young male and of a son.[14]

| Author | Work | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Full length descriptions in mythological literature | ||

| Stasinus of Cyprus? | Cypria | late 7th century BC (lost) |

| Phrynichus | Troilos | 6th–5th century BC (lost) |

| Sophocles | Troilos | 5th century BC (lost) |

| Strattis | Troilos | 5th–4th century BC (lost) |

| Dares Phrygius | de excidio Trojae historia | parts written 1st–6th century? |

| Briefer references in mythological literature | ||

| Homer | Iliad | 8th–7th century BC |

| Stesichorus | possibly in Iliupersis | 7th–6th century BC (lost) |

| Ibycus | unknown text of which only a few words survive | late 6th century BC |

| Sophocles | Polyxene | 5th century BC (lost) |

| Lycophron | Alexandra | 3rd century BC? |

| Virgil | Aeneid | 29–19 BC |

| Seneca the Younger | Agamemnon | 1st century |

| Dictys Cretensis | Ephemeridos belli Trojani | 1st–3rd century |

| Ausonius | Epitaphs | 4th century |

| Quintus of Smyrna | Posthomerica | Late 4th century? |

| Literary allusions to Troilus | ||

| Ibycus | Polycrates poem | late 6th century BC |

| Callimachus | Epigrams | 3rd century BC |

| Plautus | Bacchides | 3rd–2nd century BC |

| Cicero | Tusculanae Quaestiones | c.45 BC |

| Horace | Odes Book 2 | 23 BC |

| Statius | Silvae | Late 1st century |

| Dio Chrysostom | Discourses | 1st–2nd centuries |

| "Clement" | Clementine Homilies | 2nd century? |

| Ancient and medieval academic commentaries on and summaries of ancient literature. | ||

| Various anonymous authors | Scholia to the Iliad | 5th century BC to 9th century? |

| Hyginus | Fabulae | 1st century BC – 1st century AD |

| The "Pseudo-Apollodorus" | Library | 1st–2nd century |

| Eutychius Proclus? | Chrestomathy | 2nd century? |

| Servius | Scholia to the Aeneid | Late 4th century |

| First Vatican Mythographer | Mythography | 9th–11th century? |

| Eustathius of Thessalonica | Scholia to the Iliad | 12th century |

| John Tzetzes | Scholia to the Alexandra | 12th century |

Troilus' death was also described in the Cypria, one of the parts of the Epic Cycle that is no longer extant. The poem covered the events preceding the Trojan War and the first part of the war itself up to the events of the Iliad. Although the Cypria does not survive, most of an ancient summary of the contents, thought to be by Eutychius Proclus, remains. Fragment 1 mentions that Achilles killed Troilus, but provides no more detail.[15] However, Sommerstein takes the verb used to describe the killing (phoneuei) as meaning that Achilles murders Troilus.[16]

In Athens, the early tragedians Phrynicus and Sophocles both wrote plays called Troilos and the comic playwright Strattis wrote a parody of the same name. Of the esteemed Nine lyric poets of the archaic and classical periods, Stesichorus may have referred to Troilus' story in his Iliupersis and Ibycus may have written in detail about the character. With the exception of these authors, no other pre-Hellenistic written source is known to have considered Troilus at any length.[17]

Unfortunately, all that remains of these texts are the smallest fragments or summaries and references to them by other authors. What does survive can be in the form of papyrus fragments, plot summaries by later authors or quotations by other authors. In many cases these are just odd words in lexicons or grammar books with an attribution to the original author.[18] Reconstructions of the texts are necessarily speculative and should be viewed with "wary but sympathetic scepticism".[19] In Ibycus' case all that remains is a parchment fragment containing a mere six or seven words of verse accompanied with a few lines of scholia. Troilus is described in the poem as godlike and is killed outside Troy. From the scholia, he is clearly a boy. The scholia also refer to a sister, someone "watching out" and a murder in the sanctuary of Thymbrian Apollo. While acknowledging that these details may have been reports of other later sources, Sommerstein thinks it probable that Ibycus told the full ambush story and is thus the earliest identifiable source for it.[20] Of Phrynicus, one fragment remains considered to refer to Troilus. This speaks of "the light of love glowing on his reddening cheeks".[21]

Of all these fragmentary pre-Hellenistic sources, the most is known of Sophocles Troilos. Even so, only 54 words have been identified as coming from the play.[22] Fragment 619 refers to Troilus as an andropais, a man-boy. Fragment 621 indicates that Troilus was going to a spring with a companion to fetch water or to water his horses.[23] A scholion to the Iliad[24] states that Sophocles has Troilus ambushed by Achilles while exercising his horses in the Thymbra. Fragment 623 indicates that Achilles mutilated Troilus' corpse by a method known as maschalismos. This involved preventing the ghost of a murder victim from returning to haunt their killer by cutting off the corpse's extremities and stringing them under its armpits.[25] Sophocles is thought to have also referred to the maschalismos of Troilus in a fragment taken to be from an earlier play Polyxene.[26]

Sommerstein attempts a reconstruction of the plot of the Troilos, in which the title character is incestuously in love with Polyxena and tries to discourage the interest in marrying her shown by both Achilles and Sarpedon, a Trojan ally and son of Zeus. Sommerstein argues that Troilus is accompanied on his fateful journey to his death, not by Polyxena, but by his tutor, a eunuch Greek slave.[27] Certainly there is a speaking role for a eunuch who reports being castrated by Hecuba[28] and someone reports the loss of their adolescent master.[29] The incestuous love is deduced by Sommerstein from a fragment of Strattis' parody, assumed to partially quote Sophocles, and from his understanding that the Sophocles play intends to contrast barbarian customs, including incest, with Greek ones. Sommerstein also sees this as solving what he considers the need for an explanation of Achilles' treatment of Troilus' corpse, the latter being assumed to have insulted Achilles in the process of warning him off Polyxena.[30] Italian professor of English and expert on Troilus, Piero Boitani, on the other hand, considers Troilus' rejection of Achilles' sexual advances towards him as sufficient motive for the mutilation.[31]

The Alexandra

The first surviving text with more than the briefest mention of Troilus is a Hellenistic poem dating from no earlier than the 3rd century BC: the Alexandra by the tragedian Lycophron or a namesake of his. The poem consists of the obscure prophetic ravings of Cassandra:[32]

Ay! me, for thee fair-fostered flower, too, I groan, O lion whelp, sweet darling of thy kindred, who didst smite with fiery charm of shafts the fierce dragon and seize for a little loveless while in unescapable noose him that was smitten, thyself unwounded by thy victim: thou shalt forfeit thy head and stain thy father’s altar-tomb with thy blood.[33]

This passage is explained in the Byzantine writer John Tzetzes' scholia as a reference to Troilus seeking to avoid the unwanted sexual advances of Achilles by taking refuge in his father Apollo's temple. When he refuses to come out, Achilles goes in and kills him on the altar.[34] Lycophron's scholiast also says that Apollo started to plan Achilles' death after the murder.[35] This begins to build up the elements of the version of Troilus' story given above: he is young, much loved and beautiful; he has divine ancestry, is beheaded by his rejected Greek lover and, we know from Homer, had something to do with horses. The reference to Troilus as a "lion whelp" hints at his having the potential to be a great hero, but there is no explicit reference to a prophecy linking the possibility of Troilus reaching adulthood and Troy then surviving.

Other written sources

No other extended passage about Troilus exists from before the Augustan Age by which time other versions of the character's story have emerged. The remaining sources compatible with the standard myth are considered below by theme.

- Parentage

- The Apollodorus responsible for the Library lists Troilus last of Priam and Hecuba's sons – a detail adopted in the later tradition – but then adds that it is said that the boy was fathered by Apollo.[36] On the other hand, Hyginus includes Troilus in the middle of a list of Priam's sons without further comment.[37] In the early Christian writings the Clementine Homilies, it is suggested that Apollo was Troilus' lover rather than his father.[38]

- Youthfulness

- Horace emphasises Troilus' youth by calling him inpubes ("unhairy", i.e. pre-pubescent or, figuratively, not old enough to bear arms).[39] Dio Chrysostom derides Achilles in his Trojan discourse, complaining that all that the supposed hero achieved before Homer was the capture of Troilus who was still a boy.[40]

- Prophecies

- The First Vatican Mythographer reports a prophecy that Troy will not fall if Troilus reaches the age of twenty and gives that as a reason for Achilles' ambush.[41] In Plautus, Troilus' death is given as one of three conditions that must be met before Troy would fall.[42]

- Beauty

- Ibycus, in seeking to praise his patron, compares him to Troilus, the most beautiful of the Greeks and the Trojans.[43] Dio Chrysostom refers to Troilus as one of many examples of different kinds of beauty.[44] Statius compares a beautiful dead slave missed by his master to Troilus.[45]

- Object of pederastic love

- Servius, in his scholia to the passage from Virgil discussed below, says that Achilles lures Troilus to him with a gift of doves. Troilus then dies in the Greek's embrace. Robert Graves[46] interprets this as evidence of the vigour of Achilles' love-making but Timothy Gantz[47] considers that the "how or why" of Servius' version of Troilus' death is unclear.[48] Sommerstein favours Graves's interpretation saying that murder was not a part of ancient pederastic relations and that nothing in Servius suggests an intentional killing.[49]

- Location of ambush and death

- A number of reports have come down of Troilus' death variously mentioning water, exercising horses and the Thymbra, though they do not necessarily build into a coherent whole: the First Vatican Mythographer reports that Troilus was exercising outside Troy when Achilles attacked him;[41] a commentator on Ibycus says that Troilus was slain by Achilles in the Thymbrian precinct outside Troy;[50] Eustathius of Thessalonica's commentary on the Iliad says that Troilus was exercising his horses there;[51] Apollodorus says that Achilles ambushed Troilus inside the temple of Thymbrian Apollo;[52] finally, Statius[45] reports that Troilus was speared to death as he fled around Apollo's walls.[53] Gantz struggles to make sense of what he sees as contradictory material, feeling that Achilles' running down of Troilus' horse makes no sense if Troilus was just fleeing to the nearby temple building. He speculates that the ambush at the well and the sacrifice in the temple could be two different versions of the story or, alternatively, that Achilles takes Troilus to the temple to sacrifice him as an insult to Apollo.[54]

- Mourning

- Trojan and, especially, Troilus' own family's mourning at his death seems to have epitomised grief at the loss of a child in classical civilization. Horace,[39] Callimachus[55] and Cicero[56] all refer to Troilus in this way.

Ancient art and artifact sources

Ancient Greek art, as found in pottery and other remains, frequently depicts scenes associated with Troilus' death: the ambush, the pursuit, the murder itself and the fight over his body.[57] Depictions of Troilus in other contexts are unusual. One such exception, a red-figure vase painting from Apulia c.340BC, shows Troilus as a child with Priam.[58]

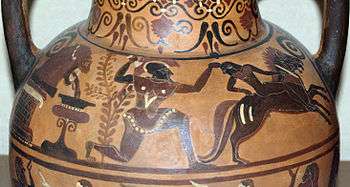

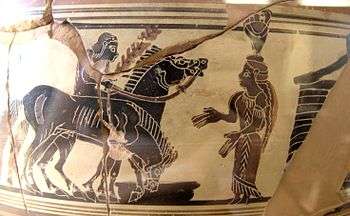

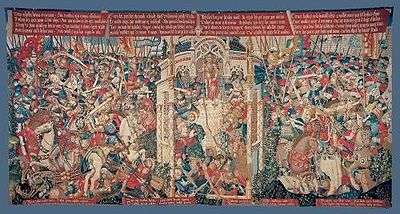

In the ambush, Troilus and Polyxena approach a fountain where Achilles lies in wait. This scene was familiar enough in the ancient world for a parody to exist from c.400BC showing a dumpy Troilus leading a mule to the fountain.[59] In most serious depictions of the scene, Troilus rides a horse, normally with a second next to him.[60] He is usually, but not always, portrayed as a beardless youth. He is often shown naked; otherwise he wears a cloak or tunic. Achilles is always armed and armoured. Occasionally, as on the vase picture at , or the fresco from the Tomb of the Bulls shown at the head of this article, either Troilus or Polyxena is absent, indicating how the ambush is linked to each of their stories. In the earliest definitely identified version of this scene, (a Corinthian vase c.580BC), Troilus is bearded and Priam is also present. Both these features are unusual.[61] More common is a bird sitting on the fountain; normally a raven, symbol of Apollo and his prophetic powers and thus a final warning to Troilus of his doom;[62] sometimes a cock, a common love gift suggesting that Achilles attempted to seduce Troilus.[63] In some versions, for example an Attic amphora in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston dating from c.530BC (seen here ) Troilus has a dog running with him. On one Etruscan vase from the 6th century BC, doves are flying from Achilles to Troilus, suggestive of the love gift in Servius.[64] The fountain itself is conventionally decorated with a lion motif.

The earliest identified version of the pursuit or chase is from the third quarter of the 7th century BC.[59] Next chronologically is the best known[65] version on the François Vase by Kleitias.[66] The number of characters shown on pottery scenes varies with the size and shape of the space available.[67] The François Vase is decorated with several scenes in long narrow strips. This means that the Troilus frieze is heavily populated. In the centre, (which can be seen at the Perseus Project at ,) is the fleeing Troilus, riding one horse with the reins of the other in his hand. Below them is the vase—which Polyxena (partially missing), who is ahead of him, has dropped. Achilles is largely missing but it is clear that he is armoured. They are running towards Troy where Antenor gestures towards Priam. Hector and Polites, brothers of Troilus, emerge from the city walls in the hope of saving Troilus. Behind Achilles are a number of deities, Athena, Thetis (Achilles' mother), Hermes, and Apollo (just arriving). Two Trojans are also present, the woman gesturing to draw the attention of a youth filling his vase. As the deities appear only in pictorial versions of the scene, their role is subject to interpretation. Boitani sees Athena as urging Achilles on and Thetis as worried by the arrival of Apollo who, as Troilus' protector, represents a future threat to Achilles.[68] He does not indicate what he thinks Hermes may be talking to Thetis about. The classicist and art historian Professor Thomas H. Carpenter sees Hermes as a neutral observer, Athena and Thetis as urging Achilles on, and the arrival of Apollo as the artist's indication of the god's future role in Achilles' death.[61] As Athena is not traditionally a patron of Achilles, Sommerstein sees her presence in this and other portrayals of Troilus' death as evidence of the early standing of the prophetic link between Troilus' death and the fall of Troy, Athena being driven, above all, by her desire for the city's destruction.[69]

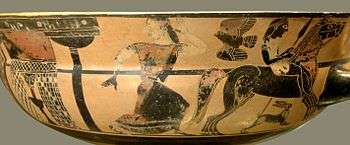

The standard elements in the pursuit scene are Troilus, Achilles, Polyxena, the two horses and the fallen vase. On two tripods, an amphora and a cup, Achilles already has Troilus by the hair.[70] A famous vase in the British Museum, which gave the Troilos Painter the name by which he is now known, shows the two Trojans looking back in fear, as the beautiful youth whips his horse on. This vase can be seen at the Perseus Project site . The water spilling from the shattered vase below Troilus' horse, symbolises the blood he is about to shed.[71]

The iconography of the eight legs and hooves of the horses can be used to identify Troilus on pottery where his name does not appear; for example, on a Corinthian vase where Troilus is shooting at his pursuers and on a peaceful scene on a Chalcidian krater where the couples Paris and Helen, Hector and Andromache are labelled, but the youth riding one of a pair of horses is not.[72]

A later Southern Italian interpretation of the story is on vases held respectively at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg. On the krater from c.380-70BC at Troilus can be seen with just one horse trying to defend himself with a throwing spear; on the hydria from c.325-320BC at , Achilles is pulling down the youth's horse.

The earliest known depictions of the death or murder of Troilus are on shield bands from the turn of the 7th into the 6th century BC found at Olympia. On these, a warrior with a sword is about to stab a naked youth at an altar. On one, Troilus clings to a tree (which Boitani takes for the laurel sacred to Apollo).[74] A crater contemporary with this shows Achilles at the altar holding the naked Troilus upside down while Hector, Aeneas and an otherwise unknown Trojan Deithynos arrive in the hope of saving the youth. In some depictions Troilus is begging for mercy. On an amphora, Achilles has the struggling Troilus slung over his shoulder as he goes to the altar.[75] Boitani, in his survey of the story of Troilus through the ages, considers it of significance that two artifacts (a vase and a sarcophagus) from different periods link Troilus' and Priam's death by showing them on the two sides of the same item, as if they were the beginning and end of the story of the fall of Troy.[76] Achilles is the father of Neoptolemus, who slays Priam at the altar during the sack of Troy. Thus the war opens with a father killing a son and closes with a son killing a father.

Some pottery shows Achilles, already having killed Troilus, using his victim's severed head as a weapon as Hector and his companions arrive too late to save him; some includes the watching Athena, occasionally with Hermes. At is one such picture showing Achilles fighting Hector over the altar. Troilus' body is slumped and the boy's head is either flying through the air, or stuck to the end of Achilles' spear. Athena and Hermes look on. Aeneas and Deithynos are behind Hector.

Sometimes details of the closely similar deaths of Troilus and Astyanax are exchanged.[77] shows one such image where it is unclear which murder is portrayed. The age of the victim is often an indicator of which story is being told and the relative small size here might point towards the death of Astyanax, but it is common to show even Troilus as much smaller than his murderer, (as is the case with the kylix pictured to the above right). Other factors in this case are the presence of Priam (suggesting Astyanax), that of Athena (suggesting Troilus) and the fact that the scene is set outside the walls of Troy (again suggesting Troilus).[78]

A variant myth: the boy-soldier overwhelmed

A different version of Troilus' death appears on a red-figure cup by Oltos. Troilus is on his knees, still in the process of drawing his sword when Achilles' spear has already stabbed him and Aeneas comes too late to save him. Troilus wears a helmet, but it is pushed up to reveal a beautiful young face. This is the only such depiction of Troilus' death in early figurative art.[79] However, this version of Troilus as a youth defeated in battle appears also in written sources.

Virgil and other Latin sources

This version of the story appears in Virgil's Aeneid,[80] in a passage describing a series of paintings decorating the walls of a temple of Juno. The painting immediately next to the one depicting Troilus shows the death of Rhesus, another character killed because of prophecies linked to the fall of Troy. Other pictures are similarly calamitous.

In a description whose pathos is heightened by the fact that it is seen through a compatriot's eyes,[81] Troilus is infelix puer ("unlucky boy") who has met Achilles in "unequal" combat. Troilus' horses flee while he, still holding their reins, hangs from the chariot, his head and hair trailing behind while the backward-pointing spear scribbles in the dust. (The First Vatican Mythographer[41] elaborates on this story, explaining that Troilus's body is dragged right to the walls of Troy.[82])

In his commentary on the Aeneid, Servius[48] considers this story as a deliberate departure from the "true" story, bowdlerized to make it more suitable for an epic poem. He interprets it as showing Troilus overpowered in a straight fight. Gantz,[83] however, argues that this might be a variation of the ambush story. For him, Troilus is unarmed because he went out not expecting combat and the backward pointing spear was what Troilus was using as a goad in a manner similar to characters elsewhere in the Aeneid. Sommerstein, on the other hand believes that the spear is Achilles' that has struck Troilus in the back. The youth is alive but mortally wounded as he is being dragged towards Troy.[84]

An issue here is the ambiguity of the word congressus ("met"). It often refers to meeting in a conventional combat but can have reference to other types of meetings too. A similar ambiguity appears in Seneca[85] and in Ausonius' 19th epitaph,[86] narrated by Troilus himself. The dead prince tells how he has been dragged by his horses after falling in unequal battle with Achilles. A reference in the epitaph comparing Troilus' death to Hector's suggests that Troilus dies later than in the traditional narrative, something that, according to Boitani,[87] also happens in Virgil.

Greek writers in the boy-soldier tradition

Quintus of Smyrna, in a passage whose atmosphere Boitani describes as sad and elegiac, retains what for Boitani are the two important issues of the ancient story, that Troilus is doomed by Fate and that his failure to continue his line symbolises Troy's fall.[88] In this case, there is no doubt that Troilus entered battle knowingly, for in the Posthomerica Troilus's armour is one of the funerary gifts after Achilles' own death. Quintus repeatedly emphasises Troilus's youth: he is beardless, virgin of a bride, childlike, beautiful, the most godlike of all Hecuba's children. Yet he was lured by Fate to war when he knew no fear and was struck down by Achilles' spear just as a flower or corn that has borne no seed is killed by the gardener.[89]

In the Ephemeridos belli Trojani (Journal of the Trojan War),[90] supposedly written by Dictys the Cretan during the Trojan War itself, Troilus is again a defeated warrior, but this time captured with his brother Lycaon. Achilles vindictively orders that their throats be slit in public, because he is angry that Priam has failed to advance talks over a possible marriage to Polyxena. Dictys' narrative is free from gods and prophecy but he preserves Troilus' loss as something to be greatly mourned:

The Trojans raised a cry of grief and, mourning loudly, bewailed the fact that Troilus had met so grievous a death, for they remembered how young he was, who being in the early years of his manhood, was the people's favourite, their darling, not only because of his modesty and honesty, but more especially because of his handsome appearance.[91]

The story in the medieval and Renaissance eras

In the sources considered so far, Troilus' only narrative function is his death.[92] The treatment of the character changes in two ways in the literature of the medieval and renaissance periods. First, he becomes an important and active protagonist in the pursuit of the Trojan War itself. Second, he becomes an active heterosexual lover, rather than the passive victim of Achilles' pederasty. By the time of John Dryden's neo-classical adaptation of Shakespeare's Troilus and Cressida it is the ultimate failure of his love affair that defines the character.

For medieval writers, the two most influential ancient sources on the Trojan War were the purported eye-witness accounts of Dares the Phrygian, and Dictys the Cretan, which both survive in Latin versions. In Western Europe the Trojan side of the war was favoured and therefore Dares was preferred over Dictys.[93] Although Dictys' account positions Troilus' death later in the war than was traditional, it conforms to antiquity's view of him as a minor warrior if one at all. Dares' De excidio Trojae historia (History of the Fall of Troy)[94] introduces the character as a hero who takes part in events beyond the story of his death.

Authors of the 12th and 13th centuries such as Joseph of Exeter and Albert of Stade continued to tell the legend of the Trojan War in Latin in a form that follows Dares' tale with Troilus remaining one of the most important warriors on the Trojan side. However, it was two of their contemporaries, Benoît de Sainte-Maure in his French verse romance and Guido delle Colonne in his Latin prose history, both also admirers of Dares, who were to define the tale of Troy for the remainder of the medieval period. The details of their narrative of the war were copied, for example, in the Laud and Lydgate Troy Books and also in Raoul Lefevre's Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye. Lefevre, through Caxton's 1474 printed translation, was in turn to become the best known retelling of the Troy story in Renaissance England and influenced Shakespeare among others. The story of Troilus as a lover, invented by Benoît and retold by Guido, generated a second line of influence. It was taken up as a tale that could be told in its own right by Boccaccio and then by Chaucer who established a tradition of retelling and elaborating the story in English-language literature, which was to be followed by Henryson and Shakespeare.

The second Hector, wall of Troy

As indicated above, it was through the writings of Dares the Phrygian that the portrayal of Troilus as an important warrior was transmitted to medieval times. However, some authors have argued that the tradition of Troilus as a warrior may be older. The passage from the Iliad described above is read by Boitani[95] as implying that Priam put Troilus on a par with the very best of his warrior sons. The description of him in that passage as hippiocharmên is rendered by some authorities as meaning a warrior charioteer rather than merely someone who delights in horses.[12] The many missing and partial literary sources might include such a hero. Yet only the one ancient vase shows Troilus as a warrior falling in a conventional battle.[79]

| Author | Work | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Followers of Dares | ||

| Joseph of Exeter | De bello Troiano | late 12th century |

| Albertus Stadensis | Troilus | finished 1249 |

| (Two other versions) | ||

| Followers of Dictys | ||

| (Eight largely in Greek) | ||

| Combining Dares and Dictys | ||

| Benoît de Sainte-Maure | Roman de Troie | finished c. 1184 |

| Followers of Benoît | ||

| Guido delle Colonne | Historia destructionis Troiae | published 1287 |

| (at least 19 other versions) | ||

| Followers of Guido | ||

| Giovanni Boccaccio | Il Filostrato | c. 1340 |

| Unknown | Laud Troy Book | c. 1400 |

| John Lydgate | Troy Book | commissioned 1412 |

| Raoul Lefevre | Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye | by 1464 |

| (at least 16 other versions) | ||

| Followers of Lefevre | ||

| William Caxton | printed translation of the Recuyell | c. 1474 |

| William Shakespeare | Troilus and Cressida | by 1603 |

| (Several other versions) | ||

Dares

In Dares, Troilus is the youngest of Priam's royal sons, bellicose when peace or truces are suggested and the equal of Hector in bravery, "large and most beautiful... brave and strong for his age, and eager for glory."[97] He slaughters many Greeks, wounds Achilles and Menelaus, routs the Myrmidons more than once before his horse falls and traps him and Achilles takes the opportunity to put an end to his life. Memnon rescues the body, something that didn't happen in many later versions of the tale. Troilus' death comes near the end of the war not at its beginning. He now outlives Hector and succeeds him as the Trojans' great leader in battle. Now it is in reaction to Troilus's death that Hecuba plots Achilles' murder.

As the tradition of Troilus the warrior advances through time, the weaponry and the form of combat change. Already in Dares he is a mounted warrior, not a charioteer or foot warrior, something anachronistic to epic narrative.[98] In later versions he is a knight with armour appropriate to the time of writing who fights against other knights and dukes. His expected conduct, including his romance, conforms to courtly or other values contemporary to the writing.

Description in medieval texts

The medieval texts follow Dares' structuring of the narrative in describing Troilus after his parents and four royal brothers Hector, Paris, Deiphobus and Helenus.

Joseph of Exeter, in his Daretis Phrygii Ilias De bello Troiano (The Iliad of Dares the Phrygian on the Trojan War), describes the character as follows:

The limbs of Troilus expand and fill his space.

In mind a giant, though a boy in years, he yields

to none in daring deeds with strength in all his parts

his greater glory shines throughout his countenance.[99]

Benoît de Sainte-Maure's description in Le Roman de Troie (The Romance of Troy) is too long to quote in full, but influenced the descriptions that follow. Benoît goes into details of character and facial appearance avoided by other writers. He tells that Troilus was "the fairest of the youths of Troy" with:

fair hair, very charming and naturally shining, eyes bright and full of gaiety... He was not insolent or haughty, but light of heart and gay and amorous. Well was he loved, and well did he love...[100]

Guido delle Colonne's Historia destructionis Troiae (History of the Destruction of Troy) says:

The fifth and last was named Troilus, a young man as courageous as possible in war, about whose valour there are many tales which the present history does not omit later on.[101]

The Laud Troy Book:

The youngest doughti Troylus

A doughtier man than he was on

Of hem alle was neuere non,-

Save Ector, that was his brother

There never was goten suche another.[102]

The boy who in the ancient texts was never Achilles' match has now become a young knight, a worthy opponent to the Greeks.

Knight and war leader

In the medieval and renaissance tradition, Troilus is one of those who argue most for war against the Greeks in Priam's council. In several texts, for example the Laud Troy Book, he says that those who disagree with him are better suited to be priests.[103] Guido, and writers who follow him, have Hector, knowing how headstrong his brother can be, counsel Troilus not to be reckless before the first battle.[104]

In the medieval texts, Troilus is a doughty knight throughout the war, taking over, as in Dares, after Hector's death as the main warrior on the Trojan side. Indeed he is named as a second Hector by Chaucer and Lydgate.[105] These two poets follow Boccaccio in reporting that Troilus kills thousands of Greeks.[106] However, the comparison with Hector can be seen as acknowledging Troilus' inferiority to his brother through the very need to mention him.[107]

In Joseph, Troilus is greater than Alexander, Hector, Tydeus, Bellona and even Mars, and kills seven Greeks with one blow of his club. He does not strike at opponents' legs because that would demean his victory. He only fights knights and nobles, and disdains facing the common warriors.

Albert of Stade saw Troilus as so important that he is the title character of his version of the Trojan War. He is "the wall of his homeland, Troy's protection, the rose of the military...."[108]

The list of Greek leaders Troilus wounds expands in the various re-tellings of the war from the two in Dares to also include Agamemnon, Diomedes and Menelaus. Guido, in keeping his promise to tell of all Troilus' valorous deeds, describes many incidents. Troilus is usually victorious but is captured in an early battle by Menestheus before his friends rescue him. This incident reappears in the imitators of Guido, such as Lefevre and the Laud and Lydgate Troy Books.[109]

Death

Within the medieval Trojan tradition, Achilles withdraws from fighting in the war because he is to marry Polyxena. Eventually, so many of his followers are killed that he decides to rejoin the battle leading to Troilus' death and, in turn, to Hecuba, Polyxena and Paris plotting Achilles' murder.

Albert and Joseph follow Dares in having Achilles behead Troilus as he tries to rise after his horse falls. In Guido and authors he influenced, Achilles specifically seeks out Troilus to avenge a previous encounter where Troilus has wounded him. He therefore instructs the Myrmidons to find Troilus, surround him and cut him off from rescue.

In the Laud Troy Book, this is because Achilles almost killed Troilus in the previous fight but the Trojan was rescued. Achilles wants to make sure that this does not happen again. This second combat is fought as a straight duel between the two with Achilles, the greater warrior, winning.

In Guido, Lefevre and Lydgate Troilus' killer's behaviour is very different, shorn of any honour. Achilles waits until his men have killed Troilus' horse and cut loose his armour. Only then

And when he sawe how Troilus nakid stod,

Of longe fightyng awaped and amaat

And from his folke alone disolat

- Lydgate, Troy Book, iv, 2756-8.

does Achilles attack and behead him.

In an echo of the Iliad, Achilles drags the corpse behind his horse. Thus, the comparison with the Homeric Hector is heightened and, at the same time, aspects of the classical Troilus's fate are echoed.

The lover

The last aspect of the character of Troilus to develop in the tradition has become the one for which he is best known. Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde and Shakespeare's Troilus and Cressida both focus on Troilus in his role as a lover. This theme is first introduced by Benoît de Sainte-Maure in the Roman de Troie and developed by Guido delle Colonne. Boccaccio's Il Filostrato is the first book to take the love-story as its main theme. Robert Henryson and John Dryden are other authors who dedicate works to it.

The story of Troilus' romance developed within the context of the male-centred conventions of courtly love and thus the focus of sympathy was to be Troilus and not his beloved.[111] As different authors recreated the romance, they would interpret it in ways affected both by the perspectives of their own times and their individual preoccupations. The story as it would later develop through the works of Boccaccio, Chaucer and Shakespeare is summarised below.

The story of Troilus and Cressida

Troilus used to mock the foolishness of other young men's love affairs. But one day he sees Cressida in the temple of Athena and falls in love with her. She is a young widow and daughter of the priest Calchas who has defected to the Greek camp.

Embarrassed at having become exactly the sort of person he used to ridicule, Troilus tries to keep his love secret. However, he pines for Cressida and becomes so withdrawn that his friend Pandarus asks why he is unhappy and eventually persuades Troilus to reveal his love.

Pandarus offers to act as a go-between, even though he is Cressida's relative and should be guarding her honour. Pandarus convinces Cressida to admit that she returns Troilus' love and, with Pandarus's help, the two are able to consummate their feelings for each other.

Their happiness together is brought to an end when Calchas persuades Agamemnon to arrange Cressida's return to him as part of a hostage exchange in which the captive Trojan Antenor is freed. The two lovers are distraught and even think of eloping together but they finally cooperate with the exchange. Despite Cressida's initial intention to remain faithful to Troilus, the Greek warrior Diomedes wins her heart. When Troilus learns of this, he seeks revenge on Diomedes and the Greeks and dies in battle. Just as Cressida betrayed Troilus, Antenor was later to betray Troy.

Benoît and Guido

In the Roman de Troie, the daughter of Calchas whom Troilus loves is called Briseis. Their relationship is first mentioned once the hostage exchange has been agreed:

Whoever had joy or gladness, Troilus suffered affliction and grief. That was for the daughter of Calchas, for he loved her deeply. He had set his whole heart on her; so mightily was he possessed by his love that he thought only of her. She had given herself to him, both her body and her love. Most men knew of that.[112]

In Guido, Troilus' and Diomedes' love is now called Briseida. His version (a history) is more moralistic and less touching, removing the psychological complexity of Benoît's (a romance) and the focus in his retelling of the love triangle is firmly shifted to the betrayal of Troilus by Briseida. Although Briseida and Diomedes are most negatively caricatured by Guido's moralising, even Troilus is subject to criticism as a "fatuous youth" prone, as in the following, to youthful faults.[113]

Troilus, however, after he had learned of his father's intention to go ahead and release Briseida and restore her to the Greeks, was overwhelmed and completely wracked by great grief, and almost entirely consumed by tears, anguished sighs, and laments, because he cherished her with the great fervour of youthful love and had been led by the excessive ardour of love into the intense longing of blazing passion. There was no one of his dear ones who could console him.[114]

Briseis, at least for now, is equally affected by the possibility of separation from her lover. Troilus goes to her room and they spend the night together, trying to comfort each other. Troilus is part of the escort to hand her over the next day. Once she is with the Greeks, Diomedes is immediately struck by her beauty. Although she is not hostile, she cannot accept him as her lover. Meanwhile Calchas tells her to accept for herself that the gods have decreed Troy's fall and that she is safer now she is with the Greeks.

A battle soon takes place and Diomedes unseats Troilus from his horse. The Greek sends it as a gift to Briseis/Briseida with an explanation that it had belonged to her old lover. In Benoît, Briseis complains at Diomedes' seeking to woo her by humbling Troilus, but in Guido all that remains of her long speech in Benoît is that she "cannot hold him in hatred who loves me with such purity of heart."[115]

Diomedes soon does win her heart. In Benoît, it is through his display of love and she gives him her glove as a token. Troilus seeks him out in battle and utterly defeats him. He saves Diomedes' life, only so that he can bring her a message of Troilus' contempt. In Guido, Briseida's change of heart comes after Troilus wounds Diomedes seriously. Briseida tends Diomedes and then decides to take him as her lover, because she does not know if she will ever meet Troilus again.

In later medieval tellings of the war, the episode of Troilus and Briseida/Cressida is acknowledged and often given as a reason for Diomedes and Troilus to seek each other out in battle. The love story also becomes one that is told separately.

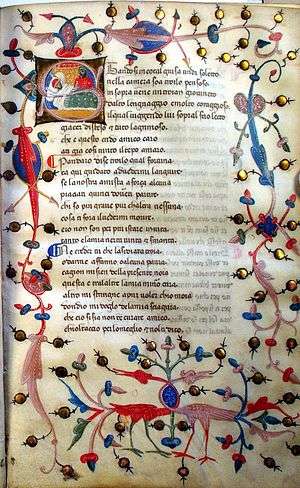

Boccaccio

The first major work to take the story of Troilus' failed love as its central theme is Giovanni Boccaccio's Il Filostrato.[116] The title means "the one struck down by love".[117] There is an overt purpose to the text. In the proem, Boccaccio himself is Filostrato and addresses his own love who has rejected him.[118]

Boccaccio introduces a number of features of the story that were to be taken up by Chaucer. Most obvious is that Troilus' love is now called Criseida or Cressida.[119] An innovation in the narrative is the introduction of the go-between Pandarus. Troilus is characterised as a young man who expresses whatever moods he has strongly, weeping when his love is unsuccessful, generous when it is.

Boccaccio fills in the history before the hostage exchange as follows. Troilus mocks the lovelorn glances of other men who put their trust in women before falling victim to love himself when he sees Cressida, here a young widow, in the Palladium, the temple of Athena. Troilus keeps his love secret and is made miserable by it. Pandarus, Troilus' best friend and Cressida's cousin in this version of the story, acts as go-between after persuading Troilus to explain his distress. In accordance with the conventions of courtly love, Troilus' love remains secret from all except Pandarus,[120] until Cassandra eventually divines the reason for Troilus' subsequent distress.

After the hostage exchange is agreed, Troilus suggests elopement, but Cressida argues that he should not abandon Troy and that she should protect her honour. Instead, she promises to meet him within ten days. Troilus spends much of the intervening time on the city walls, sighing in the direction where Cressida has gone. No horses or sleeves, as used by Guido or Benoît, are involved in Troilus' learning of Cressida's change of heart. Instead a dream hints at what has happened, and then the truth is confirmed when a brooch – previously a gift from Troilus to Cressida – is found on Diomedes' looted clothing. In the meantime, Cressida has kept up the pretence in their correspondence that she still loves Troilus. After Cressida's betrayal is confirmed, Troilus becomes ever fiercer in battle.

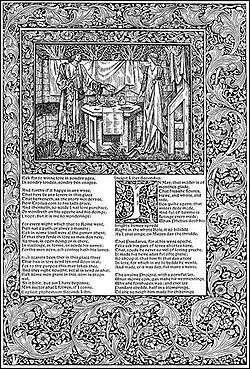

Chaucer and his successors

Geoffrey Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde[121] reflects a more humorous world-view than Boccaccio's poem. Chaucer does not have his own wounded love to display and therefore allows himself an ironic detachment from events and Criseyde is more sympathetically portrayed.[122] In contrast to Boccaccio's final canto, which returns to the poet's own situation, Chaucer's palinode has Troilus looking down laughing from heaven, finally aware of the meaninglessness of earthly emotions. About a third of the lines of the Troilus are adapted from the much shorter Il Filostrato, leaving room for a more detailed and characterised narrative.[123]

Chaucer's Criseyde is swayed by Diomedes playing on her fear. Pandarus is now her uncle, more worldly-wise and more active in what happens and so Troilus is more passive.[124] This passivity is given comic treatment when Troilus passes out in Criseyde's bedroom and is lifted into her bed by Pandarus. Troilus' repeated emotional paralysis is comparable to that of Hamlet who may have been based on him. It can be seen as driven by loyalty both to Criseyde and to his homeland, but has also been interpreted less kindly.[125]

Another difference in Troilus' characterisation from the Filostrato is that he is no longer misogynistic in the beginning. Instead of mocking lovers because of their putting trust in women, he mocks them because of how love affects them.[126] Troilus' vision of love is stark: total commitment offers total fulfilment; any form of failure means total rejection. He is unable to comprehend the subtleties and complexities that underlie Criseyde's vacillations and Pandarus' manoeuvrings.[127]

In his storytelling Chaucer links the fates of Troy and Troilus, the mutual downturn in fortune following the exchange of Criseyde for the treacherous Antenor being the most significant parallel.[128] Little has changed in the general sweep of the plot from Boccaccio. Things are just more detailed, with Pandarus, for example, involving Priam's middle son Deiphobus during his attempts to unite Troilus and Cressida. Another scene that Chaucer adds was to be reworked by Shakespeare. In it, Pandarus seeks to persuade Cressida of Troilus' virtues over those of Hector, before uncle and niece witness Troilus returning from battle to public acclaim with much damage to his helmet. Chaucer also includes details from the earlier narratives. So, reference is made not just to Boccaccio's brooch, but to the glove, the captured horse and the battles of the two lovers in Benoît and Guido.

Because of the great success of the Troilus, the love story was popular as a free standing tale to be retold by English-language writers throughout the 15th and 16th centuries and into the 17th century. The theme was treated either seriously or in burlesque. For many authors, true Troilus, false Cresseid and pandering Pandarus became ideal types eventually to be referred to together as such in Shakespeare.[129]

During the same period, English retellings of the broader theme of the Trojan War tended to avoid Boccaccio's and Chaucer's additions to the story, though their authors, including Caxton, commonly acknowledged Chaucer as a respected predecessor. John Lydgate's Troy Book is an exception.[130] Pandarus is one of the elements from Chaucer's poem that Lydgate incorporates, but Guido provides his overall narrative framework. As with other authors, Lydgate's treatment contrasts Troilus' steadfastness in all things with Cressida's fickleness. The events of the war and the love story are interwoven. Troilus' prowess in battle markedly increases once he becomes aware that Diomedes is beginning to win Cressida's heart, but it is not long after Diomedes final victory in love when Achilles and his Myrmidon's treacherously attack and kill Troilus and maltreat his corpse, concluding Lydgate's treatment of the character as an epic hero,[131] who is the purest of all those who appear in the Troy Book.[132]

Of all the treatments of the story of Troilus and, especially, Cressida in the period between Chaucer and Shakespeare, it is Robert Henryson's that receives the most attention from modern critics. His poem The Testament of Cresseid is described by the Middle English expert C. David Benson as the "only fifteenth century poem written in Great Britain that begins to rival the moral and artistic complexity of Chaucer's Troilus".[133] In the Testament the title-character is abandoned by Diomedes and then afflicted with leprosy so that she becomes unrecognizable to Troilus. He pities the lepers she is with and is generous to her because she reminds him of the idol of her in his mind, but he remains the virtuous pagan knight and does not achieve the redemption that she does. Even so, following Henryson Troilus was seen as a representation of generosity.[134]

Shakespeare and Dryden

Another approach to Troilus' love story in the centuries following Chaucer is to treat Troilus as a fool, something Shakespeare does in allusions to him in plays leading up to Troilus and Cressida.[135] In Shakespeare's "problem play"[136] there are elements of Troilus the fool. However, this can be excused by his age. He is an almost beardless youth, unable to fully understand the workings of his own emotions, in the middle of an adolescent infatuation, more in love with love and his image of Cressida than the real woman herself.[137] He displays a mixture of idealism about eternally faithful lovers and of realism, condemning Hector's "vice of mercy".[138] His concept of love involves both a desire for immediate sexual gratification and a belief in eternal faithfulness.[139] He also displays a mixture of constancy, (in love and supporting the continuation of war) and inconsistency (changing his mind twice in the first scene on whether to go to battle or not). More a Hamlet than a Romeo,[140] by the end of the play his illusions of love shattered and Hector dead, Troilus might show signs of maturing, recognising the nature of the world, rejecting Pandarus and focusing on revenge for his brother's death rather than for a broken heart or a stolen horse.[141] The novelist and academic Joyce Carol Oates, on the other hand, sees Troilus as beginning and ending the play in frenzies – of love and then hatred. For her, Troilus is unable to achieve the equilibrium of a tragic hero despite his learning experiences, because he remains a human-being who belongs to a banal world where love is compared to food and cooking and sublimity cannot be achieved.[142]

Troilus and Cressida's sources include Chaucer, Lydgate, Caxton and Homer,[143] but there are creations of Shakespeare's own too and his tone is very different. Shakespeare wrote at a time when the traditions of courtly love were dead and when England was undergoing political and social change.[144] Shakespeare's treatment of the theme of Troilus' love is much more cynical than Chaucer's, and the character of Pandarus is now grotesque. Indeed, all the heroes of the Trojan War are degraded and mocked.[145] Troilus' actions are subject to the gaze and commentary of both the venal Pandarus and of the cynical Thersites who tells us:

...That dissembling abominable varlet Diomed has got that same scurvy, doting, foolish knave's sleeve of Troy there in his helm. I would fain see them meet, that that same young Trojan ass, that loves the whore there, might send that Greekish whoremasterly villain with the sleeve back to the dissembling luxurious drab of a sleeveless errand...[146]

The action is compressed and truncated, beginning in medias res with Pandarus already working for Troilus and praising his virtues to Cressida over those of the other knights they see returning from battle, but comically mistaking him for Deiphobus. The Trojan lovers are together only one night before the hostage exchange takes place. They exchange a glove and a sleeve as love tokens, but the next night Ulysses takes Troilus to Calchas' tent, significantly near Menelaus' tent.[147] There they witness Diomedes successfully seducing Cressida after taking Troilus' sleeve from her. The young Trojan struggles with what his eyes and ears tell him, wishing not to believe it. Having previously considered abandoning the senselessness of war in favour of his role of lover and having then sought to reconcile love and knightly conduct, he is now left with war as his only role.[148]

Both the fights between Troilus and Diomedes from the traditional narrative of Benoît and Guido take place the next day in Shakespeare's retelling. Diomedes captures Troilus' horse in the first fight and sends it to Cressida. Then the Trojan triumphs in the second, though Diomedes escapes. But in a deviation from this narrative it is Hector, not Troilus, whom the Myrmidons surround in the climatic battle of the play and whose body is dragged behind Achilles' horse. Troilus himself is left alive vowing revenge for Hector's death and rejecting Pandarus. Troilus' story ends, as it began, in medias res with him and the remaining characters in his love-triangle remaining alive.

Some seventy years after Shakespeare's Troilus was first presented, John Dryden re-worked it as a tragedy, in his view strengthening Troilus' character and indeed the whole play, by removing many of the unresolved threads in the plot and ambiguities in Shakespeare's portrayal of the protagonist as a believable youth rather than a clear-cut and thoroughly sympathetic hero.[149] Dryden described this as "remov[ing] that heap of Rubbish, under which many excellent thoughts lay bury'd."[150] His Troilus is less passive on stage about the hostage exchange, arguing with Hector over the handing over of Cressida, who remains faithful. Her scene with Diomedes that Troilus witnesses is her attempt "to deceive deceivers".[151] She throws herself at her warring lovers' feet to protect Troilus and commits suicide to prove her loyalty. Unable to leave a still living Troilus on the stage, as Shakespeare did, Dryden restores his death at the hands of Achilles and the Myrmidons but only after Troilus has killed Diomedes. According to P. Boitani, Dryden goes to "the opposite extreme of Shakespeare's... solv[ing] all problems and therefore kill[ing] the tragedy".[152]

Modern versions

After Dryden's Shakespeare, Troilus is almost invisible in literature until the 20th century. Keats does refer to Troilus and Cressida in the context of the "sovereign power of love"[153] and Wordsworth translated some of Chaucer but, as a rule, love was portrayed in ways far different from how it is in the Troilus and Cressida story.[154] Boitani sees the two World Wars and the 20th century's engagement "in the recovery of all sorts of past myths"[155] as contributing to a rekindling of interest in Troilus as a human being destroyed by events beyond his control. Similarly Foakes sees the aftermath of one World War and the threat of a second as key elements for the successful revival of Shakespeare's Troilus in two productions in the first half of the 20th century,[156] and one of the authors discussed below names Barbara Tuchman's The March of Folly: From Troy to Vietnam as the trigger for his wish to retell the Trojan war.[157]

Boitani discusses the modern use of the character of Troilus in a chapter entitled Eros and Thanatos.[158] Love and death, the latter either as a tragedy in itself or as an epic symbol of Troy's own destruction, therefore, are the two core elements of the Troilus myth for the editor of the first book-length survey of it from ancient to modern times. He sees the character as incapable of transformation on a heroic scale in the manner of Ulysses and also blocked from the possibility of development as an archetypal figure of troubled youth by Hamlet. Troilus' appeal for the 20th and 21st century is his very humanity.[155]

Belief in the medieval tradition of the Trojan War that followed Dictys and Dares survived the Revival of Learning in the Renaissance and the advent of the first English translation of the Iliad in the form of Chapman's Homer. (Shakespeare used both Homer and Lefevre as sources for his Troilus.) However the two supposedly eye-witness accounts were finally discredited by Jacob Perizonius in the early years of the 18th century.[159] With the chief source for his portrayal as one of the most active warriors of the Trojan War undermined, Troilus has become an optional character in modern Trojan fiction, except for those that retell the love story itself. Lindsay Clarke and Phillip Parotti, for example, omit Troilus altogether. Hilary Bailey includes a character of that name in Cassandra: Princess of Troy but little remains of the classical or medieval versions except that he fights Diomedes. However, some of the over sixty re-tellings of the Trojan War since 1916[160] do feature the character.

Once more a man-boy

One consequence of the reassessment of sources is the reappearance of Troilus in his ancient form of andropais.[161] Troilus takes this form in Giraudoux's The Trojan War Will Not Take Place, his first successful reappearance in the 20th century.[162] Troilus is a fifteen-year-old boy whom Helen has noticed following her around. After turning down the opportunity to kiss her when she offers and when confronted by Paris, he eventually accepts the kiss at the end of the play just as Troy has committed to war. He is thus a symbol of the whole city's fatal fascination with Helen.[163]

Troilus, in one of his ancient manifestations as a boy-soldier overwhelmed, reappears both in works Boitani discusses and those he does not. Christa Wolf in her Kassandra features a seventeen-year-old Troilus, first to die of all the sons of Priam. The novel's treatment of the character's death has features of both medieval and ancient versions.[164] Troilus has just gained his first love, once more called Briseis. It is only after his death that she is to betray him. On the first day of the war, Achilles seeks Troilus out and forces him into battle with the help of the Myrmidons. Troilus tries to fight in the way he has been taught princes should do, but Achilles strikes the boy down and leaps on top of him, before attempting to throttle him. Troilus escapes and runs to the sanctuary of the temple of Apollo where he is helped to take his armour off. Then, in "some of the most powerful and hair-raising" words ever written on Troilus' death,[165] Wolf describes how Achilles enters the temple, caresses then half-throttles the terrified boy, who lies on the altar, before finally beheading him like a sacrificial victim. After his death, the Trojan council propose that Troilus be officially declared to have been twenty in the hope of avoiding the prophecy about him but Priam, in his grief, refuses as this would insult his dead son further. In "exploring the violent underside of sexuality and the sexual underside of violence",[166] Wolf revives a theme suggested by the ancient vases where an "erotic aura seems to pervade representations of a fully armed Achilles pursuing or butchering a naked, boyish Troilus".[167]

Colleen McCullough is another author who incorporates both the medieval Achilles' seeking Troilus out in battle and the ancient butchery at the altar. Her The Song of Troy includes two characters, Troilos and Ilios,[168] who are Priam's youngest children – both with prophecies attached and both specifically named for the city's founders. They are eight and seven respectively when Paris leaves for Greece and somewhere in their late teens when killed. Troilos is made Priam's heir after Hector's death, against the boy's will. Odysseus's spies learn of the prophecy that Troy will not fall if Troilos comes of age. Achilles therefore seeks him out in the next battle and kills him with a spear-cast to his throat. In a reference to the medieval concept of Troilus as the second Hector, Automedon observes that "with a few more years added, he might have made another Hektor."[169] Ilios is the last son of Priam to die, killed at the altar in front of his parents by Neoptolemos.

Marion Zimmer Bradley's The Firebrand features an even younger Troilus, just twelve when he becomes Hector's charioteer. (His brother wants to keep a protective eye on him now he is ready for war.) Troilus helps kill Patroclus. Although he manages to escape the immediate aftermath of Hector's death, he is wounded. After the Trojans witness Achilles' treatment of Hector's body, Troilus insists on rejoining the battle despite his wounds and Hecuba's attempts to stop him. Achilles kills him with an arrow. The mourning Hecuba comments that he did not want to live because he blamed himself for Hector's death.

Reinventing the love story

A feature already present in the treatments of the love story by Chaucer, Henryson, Shakespeare and Dryden is the repeated reinvention of its conclusion. Boitani sees this as a continuing struggle by authors to find a satisfying resolution to the love triangle. The major difficulty is the emotional dissatisfaction resulting from how the tale, as originally invented by Benoît, is embedded into the pre-existing narrative of the Trojan War with its demands for the characters to meet their traditional fates. This narrative has Troilus, the sympathetic protagonist of the love story, killed by Achilles, a character totally disconnected from the love triangle, Diomedes survive to return to Greece victorious, and Cressida disappear from consideration as soon as it is known that she has fallen for the Greek. Modern authors continue to invent their own resolutions.[170]

William Walton's Troilus and Cressida is the best known and most successful of a clutch of 20th-century operas on the subject after the composers of previous eras had ignored the possibility of setting the story.[171] Christopher Hassall's libretto blends elements of Chaucer and Shakespeare with inventions of its own arising from a wish to tighten and compress the plot, the desire to portray Cressida more sympathetically and the search for a satisfactory ending.[172] Antenor is, as usual, exchanged for Cressida but, in this version of the tale, his capture has taken place while he was on a mission for Troilus. Cressida agrees to marry Diomedes after she has not heard from Troilus. His apparent silence, however, is because his letters to her have been intercepted. Troilus arrives at the Greek camp just before the planned wedding. When faced with her two lovers, Cressida chooses Troilus. He is then killed by Calchas with a knife in the back. Diomedes sends his body back to Priam with Calchas in chains. It is now the Greeks who condemn "false Cressida" and seek to keep her but she commits suicide.

Before Cressida kills herself she sings to Troilus to

...turn on that cold river's brim

beyond the sun's far setting.

Look back from the silent stream

of sleep and long forgetting.

Turn and consider me

and all that was ours;

you shall no desert see

but pale unwithering flowers.[173]

This is one of three references in 20th century literature to Troilus on the banks of the River Styx that Boitani has identified. Louis MacNeice's long poem The Stygian Banks explicitly takes its name from Shakespeare who has Troilus compare himself to "a strange soul upon the Stygian banks" and call upon Pandarus to transport him "to those fields where I may wallow in the lily beds".[174] In MacNeice's poem the flowers have become children, a paradoxical use of the traditionally sterile Troilus[175] who

Patrols the Stygian banks, eager to cross,

But the value is not on the further side of the river,

The value lies in his eagerness. No communion

In sex or elsewhere can be reached and kept

Perfectly for ever. The closed window,

The river of Styx, the wall of limitation

Beyond which the word beyond loses its meaning,

Are the fertilising paradox, the grille

That, severing, joins, the end to make us begin

Again and again, the infinite dark that sanctions

Our growing flowers in the light, our having children...

The third reference to the Styx is in Christopher Morley's The Trojan Horse. A return to the romantic comedy of Chaucer is the solution that Boitani sees to the problem of how the love story can survive Shakespeare's handling of it.[176] Morley gives us such a treatment in a book that revels in its anachronism. Young Lieutenant (soon to be Captain) Troilus lives his life in 1185 BC where he has carefully timetabled everything from praying, to fighting, to examining his own mistakes. He falls for Cressida after seeing her, as ever, in the Temple of Athena where she wears black, as if mourning the defection of her father, the economist Dr Calchas. The flow of the plot follows the traditional story, but the ending is changed once again. Troilus' discovery of Cressida's change of heart happens just before Troy falls. (Morley uses Boccaccio's version of the story of a brooch, or in this case a pin, attached to a piece of Diomedes' armour as the evidence that convinces the Trojan.) Troilus kills Diomedes as he exits the Trojan Horse, stabbing him in the throat where the captured piece of armour should have been. Then Achilles kills Troilus. The book ends with an epilogue. The Trojan and Greek officers exercise together by the River Styx, all enmities forgotten. A new arrival (Cressida) sees Troilus and Diomedes and wonders why they seem familiar to her. What Boitani calls "a rather dull, if pleasant, ataraxic eternity" replaces Chaucer's Christian version of the afterlife.[177]

In Eric Shanower's graphic novel Age of Bronze, currently still being serialised, Troilus is youthful but not the youngest son of Priam and Hecuba. In the first two collected volumes of this version of the Trojan War, Shanower provides a total of six pages of sources covering the story elements of his work alone. These include most of the fictional works discussed above from Guido and Boccaccio down to Morley and Walton. Shanower begins Troilus' love story with the youth making fun of Polyxena's love for Hector and in the process accidentally knocking aside Cressida's veil. He follows the latter into the temple of Athena to gawp at her. Pandarus is the widow Cressida's uncle encouraging him. Cressida rejects Troilus' initial advances not because of wanting to act in a seemly manner, as in Chaucer or Shakespeare, but because she thinks of him as just a boy. However, her uncle persuades her to encourage his affection, in the hope that being close to a son of Priam will protect against the hostility of the Trojans to the family of the traitor Calchas. Troilus' unrequited love is used as comic relief in an otherwise serious retelling of the Trojan War cycle. The character is portrayed as often indecisive and ineffectual as on the second page of this episode sample at the official site . It remains to be seen how Shanower will further develop the story.

Troilus is rewarded a rare happy ending in the early Doctor Who story The Myth Makers.[178] The script was written by Donald Cotton who had previously adapted Greek tales for the BBC Third Programme.[179] The general tone is one of high comedy combined with a "genuine atmosphere of doom, danger and chaos" with the BBC website listing A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum as an inspiration together with Chaucer, Shakespeare, Homer and Virgil.[180] Troilus is again an andropais "seventeen next birthday"[181] described as "looking too young for the military garb".[182] Both "Cressida" and "Diomede" are the assumed names of the Doctor's companions. Thus Troilus' jealousy of Diomede, whom he believes also loves Cressida, is down to confusion about the real situation. In the end "Cressida" decides to leave the Doctor for Troilus and saves the latter from the fall of Troy by finding an excuse to get him away from the city. In a reversal of the usual story, he is able to avenge Hector by killing Achilles when they meet outside Troy. (The story was originally intended to end more conventionally, with "Cressida", despite her love for him, apparently abandoning him for "Diomede", but the producers declined to renew co-star Maureen O'Brien's contract, requiring that her character Vicki be written out.)

Notes and references

- Also spelled Troilos or Troylus.

- Pierre Vidal-Naquet, Le monde d'Homère, Perrin 2000, p19

- For simplicity's sake, the Iliad and the Odyssey are here treated as part of the Epic Cycle, though the term is often used to describe solely the non-Homeric works.

- Boitani, (1989: pp.4–5).

- Burgess (2001: pp.144–5).

- Beazley Archive databases accessible from . Link accessed 12-25-2007. Note: The databases are intended only for research and academic use.

- Examples of this practice are the section "Troilos and Lykaon" by Gantz (1993: pp.597–603) and the chapter "Antiquity and Beyond: The Death of Troilus" by Boitani (1989: pp.1–19).

- Sommerstein (2007: pp. 197,196).

- This Homeric epithet is picked out as applying to Achilles in this context both in March (1998: p.389) and Sommerstein (2007: p.197).

- Burgess (2001: p.64).

- Homer Iliad (XXIV, 257) The text for the whole passage in Greek, with hotlinks to parallel English translations, is available at . (Verified 1 August 2007.)

- Carpenter (1991: p.17), March (1998: p.389), Gantz (1993: p.597) and Lattimore's translation at "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-09-04. Retrieved 2007-08-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) (and maybe Woodford (1993: p.55) interpret hippiocharmên as horse-loving; Boitani (1989: p.1), who quotes Alexander Pope's translation of the Iliad and the Liddell and Scott lexicon and translations available at the Perseus Project (checked 1 August 2007) interpret the word as meaning chariot warrior. Sommerstein (2007) wavers between the two meanings giving each in different places in the same book (p.44, p.197). The confusion over the meaning dates back to ancient times. The Scholia D (available in Greek at "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2007-08-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) link checked 14 August 2007) says that the word can mean either a horse warrior or someone who takes delight in horses (p.579). Other scholia argue that Homer cannot have considered Troilus a boy, either because he is considered one of the best or because he is described as a horse-warrior. (Scholia S-I24257a and S-I24257b respectively, available in Greek at . Link checked 14 August 2007.)

- Homer Iliad 24.506.

- Sommerstein (2007: pp. 44, 197–8).

- The text is available at . (Verified 1 August 2007.)

- Sommerstein (2007: p.198).

- All these literary sources are discussed in Boitani (1989: p.16), Sommerstein (2007) and/or Gantz (1993: p597, p.601).

- Sommerstein (2007:pp. xviii–xx).

- Malcolm Health on page 111 of "Subject Reviews: Greek Literature", Greece & Rome Vol.54, No 1. (2007), pp.111–6, (link checked 1 August 2007). On pages 112–3 Heath reviews Sommerstein et al. (2007).

- Sommerstein (2007: pp.199–200).

- 3 fr 13 Sn, cited in Gantz (1993: p.597), Sommerstein (2007: p.201) and Boitani (1989: p.16).

- Text available with parallel translation in Sommerstein (2007 pp:218–27).

- Sophocles fragment 621. Text available in the Loeb edition or Sommerstein (2007).

- Scholia S-I24257a available in Greek at . Link checked 14 August 2007. Translated and discussed in Sommerstein (2007: p.203).

- Boitani (1989: p.15); Sommerstein (207: pp. 205–8).

- Sophocles Troilus Fragment 528. Text with translation Sommerstein (2007: pp.74–5); discussed Sommerstein (2007: p.83).

- Sommerstein (2007: pp.203–12).

- Sophocles Troilus (fr.620).

- Sophocles Troilus (fr.629).

- Sommerstein (2007: pp.204–8).

- Boitani (1989, p:18).

- Boitani (1989: p.16).

- Lycophron, Alexandra 307-13, translation by A. W. Mair, in edition available from Loeb Classical Library. A PDF of a Greek manuscript is available at . (Link verified 1 August 2007.)

- Tzetzes' comments are not readily available but are discussed by Gantz (1993: p.601) and Boitani (1989: p.17).

- Sommerstein (2007: p.201).

- Apollodorus Library(III.12.5). Greek text with link to parallel English text available at . Link checked 2 August 2007.

- Hyginus Fabulae 90. English translation at . Link checked 2 August 2007.

- Clementine Homilies v. xv. 145. English translation available at "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-08-08.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). Link checked 8/8/2007.

- Horace, Odes ii. ix. 13–16. Latin Text with link to translation available at . Link checked 2 August 2007.

- Dio Chrysostom Discourses (XI, 91)

- VM (I, 120). The text is not easily available but is cited by Gantz (1993: p.602) and Sommerstein (2007: p.200, p.202) among others.

- Plautus, Bacchides 953-4. Text available in Latin with link to English translation at . Link checked 2 August 2007.

- Ibycus Polycrates poem (l.41-5). Text available in Greek with parallel German translation at . Link checked 2 August 2007.

- Dio Chrysostom Or. 21.17

- Statius Silvae 2.6 32-3. Latin text available at . Checked 29 July 2007.

- Graves, (1955, 162.g).

- Gantz (1993: p.602).

- Servius' Latin text can be seen at . Link checked 2 August 2007.

- Sommerstein (2007: pp.200–1).

- Gantz (1993: p.597).

- Eustathius on Homer's Iliad XXIV 257, cited by J. G. Frazer in footnote 79 to his translation of Apollodorus' Library. Available at . (Link checked 2 August 2007). Eustathius follows Scholion S-I24257a, available in Greek at . (Link checked 14 August 2007).

- Apollodorus Epitome (3, 32) to the Library. The text in Greek with a link to the English translation is available at . Link checked 2 August 2007.