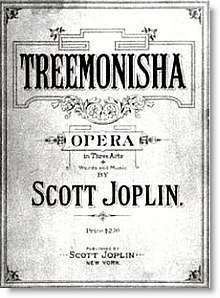

Treemonisha

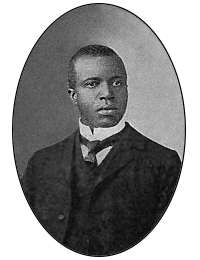

Treemonisha (1911) is an opera by American ragtime composer Scott Joplin. Though it encompasses a wide range of musical styles other than ragtime, and Joplin did not refer to it as such,[1] it is sometimes referred to as a "ragtime opera". The music of Treemonisha includes an overture and prelude, along with various recitatives, choruses, small ensemble pieces, a ballet, and a few arias.[2]

The opera was largely unknown before its first complete performance in 1972. Joplin was posthumously awarded the Pulitzer Prize for music in 1976 for Treemonisha[3]. The performance was called a "semimiracle" by music historian Gilbert Chase, who said Treemonisha "bestowed its creative vitality and moral message upon many thousands of delighted listeners and viewers" when it was recreated.[4] The musical style of the opera is the popular romantic one of the early 20th century. It has been described as "charming and piquant and ... deeply moving",[2] with elements of black folk songs and dances, including a kind of pre-blues music, spirituals, and a call-and-response style scene featuring a preacher and congregation.[5]

The opera celebrates African-American music and culture while stressing that education is the salvation of African Americans. The heroine and symbolic educator is Treemonisha, who runs into trouble with a local band of conjurers, who kidnap her.[2]

History

Joplin completed Treemonisha in 1910, and paid for a piano-vocal score to be published in 1911.[6] At the time of the publication, he sent a copy of the score to the American Musician and Art Journal. Treemonisha received a glowing, full-page review in the June issue.[7] The review said it was an "entirely new phase of musical art and... a thoroughly American opera (style)."[6] this affirmed Joplin's goal of creating a distinctive form of African-American opera.[7]

Despite this endorsement, the opera was never fully staged during his lifetime. Its sole performance was a concert read-through in 1915 with Joplin at the piano, at the Lincoln Theater in Harlem, New York, paid for by Joplin.[1] One of Joplin's friends, Sam Patterson, described this performance as "thin and unconvincing, little better than a rehearsal... its special quality (would have been) lost on the typical Harlem audience (that was) sophisticated enough to reject their folk past but not sufficiently so to relish a return to it".[8]

Aside from a concert-style performance in 1915 of the ballet Frolic of the Bears from Act II, by the Martin-Smith Music School,[9] the opera was forgotten until 1970, when the score was rediscovered. On October 22, 1971, excerpts from Treemonisha were presented in concert form at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, with musical performances by William Bolcom, Joshua Rifkin and Mary Lou Williams supporting a group of singers.[10]

The world premiere took place on January 27, 1972, as a joint production of the music department of Morehouse College and the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra in Atlanta, Georgia, using the orchestration by T. J. Anderson. The performance was directed by Katherine Dunham, former head of a noted African-American dance company in her own name, and conducted by Robert Shaw. He is one of the first major American conductors to hire both black and white singers for his chorale. The production was well received by both audiences and critics.[2]

The orchestration notes for Treemonisha have been completely lost, as has Joplin's first opera A Guest of Honor (1903). Subsequent performances have been produced using orchestrations created by a variety of composers, including T. J. Anderson, Gunther Schuller, and most recently, Rick Benjamin. Since its premiere, Treemonisha has been performed all over the United States, at venues such as the Houston Grand Opera (twice, once with Schuller's 1982 orchestration), the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., and in 1975 at the Uris Theatre on Broadway, to overwhelming critical and public acclaim. Opera historian Elise Kirk noted that

"the opera slumbered in oblivion for more than half a century before making a triumphant Broadway debut. It was also recorded commercially in its entirety – the earliest African American opera to achieve that distinction and the earliest to receive widespread modern recognition and performance."[11]

Inspiration

Joplin's ambition was for Treemonisha to be both a serious opera in the European tradition and an entertaining piece of music. He drew on the ragtime idiom only in the dance episodes.[4]

Historians have speculated that Joplin's second wife, Freddie Alexander, may have inspired the opera.[12] Like the title character, she was educated, well-read, and known to be a proponent of women's rights and African-American culture.[13] Joplin set the work in September 1884, the month and year of Alexander's birth, which contributes to that theory.[14]

Joplin biographer Edward A. Berlin has said that Treemonisha may have expressed other aspects of Joplin's life. Berlin said that the opera was "a tribute to [Freddie, his second wife] the woman he loved, a woman other biographers never even mentioned."[15] He also notes that in the opera, the title character receives her education in a white woman's home. Berlin and other music historians, along with Joplin's widow, have noted similarities between this element of the opera's story and Joplin's own childhood music and other lessons with Julius Weiss. Treemonisha, the protagonist of the opera, is a black teenager who was educated by a white woman, "just as Joplin received his education from a white music teacher".[16] Historian Larry Wolz agrees, noting that the "influence of mid-nineteenth-century German operatic style" is quite obvious in Treemonisha, which he attributes to Joplin learning from Weiss.[17]

Berlin notes that Lottie Joplin (the composer's third wife) saw a connection between the character Treemonisha's wish to lead her people out of ignorance, and a similar desire in the composer. Lottie Joplin also describes Treemonisha as a spirit who would speak to him while Scott Joplin played the piano, and she would "shape" the composition. "She'd tell him secrets. She'd tell him the past and the future," said Lottie Joplin.[15] Treemonisha was an entity present while the piece was being created and was part of the process.[15]

At the time of the opera's publication in 1911, the American Musician and Art Journal praised it as "an entirely new form of operatic art".[18] Later critics have also praised the opera as occupying a special place in American history, with its heroine "a startlingly early voice for modern civil rights causes, notably the importance of education and knowledge to African American advancement."[19] Curtis's conclusion is similar: "In the end, Treemonisha offered a celebration of literacy, learning, hard work, and community solidarity as the best formula for advancing the race."[20] Berlin describes it as a "fine opera, certainly more interesting than most operas then being written in the United States". By contrast, he says that Joplin's libretto showed the composer "was not a competent dramatist" and that the libretto was not of the same quality as the music.[21]

Plot synopsis

Treemonisha takes place in September 1884 on a former slave plantation in an isolated forest, between Texarkana, Texas (Joplin's childhood town) and the Red River in Arkansas. Treemonisha is a young freedwoman. After being taught to read by a white woman, she leads her community against the influence of conjurers, who are shown as preying on ignorance and superstition. Treemonisha is abducted and is about to be thrown into a wasps' nest when her friend Remus rescues her. The community realizes the value of education and the liability of their ignorance before choosing her as their teacher and leader.[20][22][23]

The opera opens with Zodzetrick, a conjurer, attempting to sell a bag of luck to Monisha ("The Bag of Luck"). However, her husband, Ned, wards him off. As Zodzetrick slinks away, Treemonisha and Remus hear the folks singing and excitedly prepare for the day ("The Corn Huskers"). Treemonisha then asks if they would like a ring play before they worked. They accept, and Andy leads the folks in a song and dance ("We're Goin' Around"). When the folks have finished dancing, Treemonisha notices that the women wear wreaths on their heads, and she herself tries to acquire one from a tree ("The Wreath"). However, Monisha stops her in her tracks, and tells her of how this certain tree is sacred. Monisha performs an aria, talking of Treemonisha's discovery under the tree ("The Sacred Tree"). Treemonisha is distraught to learn Monisha and Ned aren't her true parents and laments over it ("Surprised"). Monisha then tells of how Treemonisha was brought up and educated ("Treemonisha's Bringing Up"). Parson Alltalk then arrives in a wagon, talking to the neighborhood and confirming their belief in superstition. Whilst he distracts the folks, the conjurers kidnap Treemonisha ("Good Advice"). Once Alltalk leaves, the neighborhood realizes Treemonisha is gone ("Confusion"). Remus sets out to rescue Treemonisha.

Act 2 opens with Simon, another conjurer, singing of superstition ("Superstition"). Zodzetrick, Luddud and Cephus then debate on Treemonisha's punishment for foiling their plans earlier in the day ("Treemonisha in Peril"). Whilst Treemonisha is bound, strange creatures perform a dance number about her ("Frolic of the Bears"). Simon and Cephus then take Treemonisha to be thrown in a giant wasps' nest ("The Wasp Nest"), but Remus arrives just in time, masquerading as the devil, scaring the conjurers away ("The Rescue"). The next scene opens on another plantation, where four laborers perform a quartet about having a break ("We Will Rest Awhile / Song of the Cotton Pickers"). Treemonisha and Remus then arrive, and ask for directions to the John Smith plantation. Once they have left, the workers hear a horn, and celebrate that their work is finished for the day ("Aunt Dinah has Blowed de Horn").

The third act opens with a prelude ("Prelude to Act 3") in an abandoned plantation. Back in the neighborhood, Monisha and Ned mourn about Treemonisha's disappearance ("I Want to See My Child"). When Remus and Treemonisha return, the neighborhood celebrate, and show that they have captured two of the conjurers, Zodzetrick and Luddud ("Treemonisha's Return"). Remus then lectures about good and evil ("Wrong is Never Right (A Lecture)"). Andy still wants to punish the conjurers, and riles up the neighborhood to attack them ("Abuse"). Ned then lectures the conjurers about their own nature ("When Villains Ramble Far and Near (A Lecture)"). Treemonisha persuades Andy to forgive the conjurers ("Conjurers Forgiven"), and sets them both free. Luddud decides to abandon conjuring, but Zodzetrick insists that he will never change his ways. The neighborhood then elect Treemonisha as their new leader ("We Will Trust You As Our Leader"), and they celebrate with a closing dance ("A Real Slow Drag").

Characters

- Andy, friend of Treemonisha – tenor

- Cephus, a conjurer – tenor

- Lucy, friend of Treemonisha – mezzo-soprano

- Luddud, a conjurer – baritone

- Monisha, Treemonisha's supposed mother – contralto

- Ned, Treemonisha's father – bass

- Parson Alltalk, a preacher – baritone

- Remus, friend of Treemonisha – tenor

- Simon, a conjurer – bass

- Treemonisha, a young, educated freed slave – soprano

- Zodzetrick, a conjurer – baritone

Original cast

1972 Atlanta World Premiere[1]

- Alpha Floyd (Treemonisha)

- Louise Parker (Monisha)

- Seth McCoy (Remus)

- Simon Estes (Ned)

Musical numbers

Act 1

- Overture

- The Bag of Luck – Zodzetrick, Monisha, Ned, Treemonisha, Remus

- The Corn Huskers – Chorus, Treemonisha, Remus

- We're Goin' Around (A Ring Play) – Andy, Chorus

- The Wreath – Treemonisha, Lucy, Monisha, Chorus

- The Sacred Tree – Monisha

- Surprised – Treemonisha, Chorus

- Treemonisha's Bringing Up – Monisha, Treemonisha, Chorus

- Good Advice – Parson Alltalk, Chorus

- Confusion – Monisha, Chorus, Lucy, Ned, Remus

Act 2

- Superstition – Simon, Chorus

- Treemonisha in Peril – Simon, Chorus, Zodzetrick, Luddud, Cephus

- Frolic of the Bears

- The Wasp Nest – Simon, Chorus, Cephus

- The Rescue – Treemonisha, Remus

- We Will Rest Awhile / Song of the Cotton Pickers – Chorus

- Going Home – Treemonisha, Remus, Chorus

- Aunt Dinah Has Blowed de Horn – Chorus

Act 3

- Prelude to Act 3

- I Want To See My Child – Monisha, Ned

- Treemonisha's Return – Monisha, Ned, Remus, Treemonisha, Chorus, Andy, Zodzetrick, Luddud

- Wrong is Never Right (A Lecture) – Remus, Chorus

- Abuse – Andy, Chorus, Treemonisha

- When Villains Ramble Far and Near (A Lecture) – Ned

- Conjurors Forgiven – Treemonisha, Andy, Chorus

- We Will Trust You As Our Leader – Treemonisha, Chorus

- A Real Slow Drag – Treemonisha, Lucy, Chorus

Critical appraisal

Joplin wrote both the score and the libretto for the opera, which largely follows the form of European opera with many conventional arias, ensembles and choruses. In addition the themes of superstition and mysticism, which are evident in Treemonisha, are common in the operatic tradition. Certain aspects of the plot are similar to devices in the work of the German composer Richard Wagner (of which Joplin was aware); a sacred tree under which Treemonisha is found recalls the tree from which Siegmund takes his enchanted sword in Die Walküre. The recounting of the heroine's origins echos aspects of the opera Siegfried. African-American folk tales also influence the story; for instance, the wasp nest incident is similar to the story of Br'er Rabbit and the briar patch.[24]

Treemonisha is not a ragtime opera. Joplin used the styles of ragtime and other black music sparingly, to convey "racial character"; but he composed more music that reflected that of his childhood at the end of the 19th century. The opera has been seen as a valuable record of such rural Southern black music from the 1870s–1890s, re-created by a "skilled and sensitive participant".[25]

Joplin was posthumously awarded the Pulitzer Prize in music in 1976 for Treemonisha.

Staged versions

North America

Atlanta Symphony and Morehouse Glee Club

The world premiere of Treemonisha was presented in 1972 by the Atlanta Symphony,[26] under Robert Shaw, and the Morehouse Glee Club, under Wendell Whalum, the production's musical director.[27] Katherine Dunham was stage director.[28]

Houston Grand Opera

In 1976 the Houston Grand Opera first staged Treemonisha under music director Chris Nance and stage director Frank Corsaro. In 1982 the company revived that staging and produced a video of the production for television by Sidney Smith. This used the Schuller orchestration and starred Carmen Balthrop as Treemonisha, Delores Ivory as Monisha, and Obba Babatundé as Zodzetrick. Deutsche Grammophon had previously released the audio version of this production on LPs in 1976.

The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

A fully orchestrated and costumed production of Treemonisha was staged in February 1991 at the Krannert Center for the Performing Arts at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.[29]

Opera Theatre of Saint Louis

In 2000, Opera Theatre of Saint Louis presented a production of Treemonisha directed by Rhoda Levine, conducted by Jeffrey Huard, and choreographed by Dianne McIntyre. The cast included Christina Clark (Treemonisha), Geraldine McMillian (Monisha), Nathan Granner (Remus), and Kevin Short (singer) (Ned).[30] Unlike the 1976 Houston Grand Opera production and recording, this production used Joplin's original dialect.[31]

The Paragon Ragtime Orchestra

In June 2003 Rick Benjamin and the Paragon Ragtime Orchestra premiered their version of Scott Joplin's opera Treemonisha at the Stern Grove Festival in San Francisco. An extensively annotated 204-page book and two-CD recording of Benjamin's orchestration was released in 2011.[32][33]

Europe

Europe saw staged versions in Venice (Italy), Helsinki (Finland) and Gießen (Germany). After the German premiere at the Stadttheater Gießen in 1984,[34] Germany saw another stage version at the Staatsschauspiel Dresden in April 2015.[35] There were four performances in August 2019 at the Arcola Theatre, London (UK) as part of the Grimeborn Festival. [36]

Adaptations

In 1997, Aaron Robinson conducted Treemonisha: The Concert Version at the Rockport Opera House in Rockport, Maine, with a new libretto by Judith Kurtz Bogdanove.[37]

A performance of three songs from Treemonisha (Nos. 4, 27, and 18) took place at the Berlin University of the Arts on June 17, 2009. A new arrangement for singers and brass band (4 trumpets, 4 trombones, French horn, tuba) had been commissioned from German composer Stefan Beyer.[38] In April 2010, a production was mounted in Paris, France, at the Théâtre du Châtelet.[39]

In June 2008 Sue Keller produced and arranged an abridged orchestral-choral rendition of Treemonisha. The production was commissioned by the Scott Joplin International Ragtime Foundation,[40] which hosts the week-long ragtime piano extravaganza held annually in Sedalia, Missouri. The original piano-vocal music book published by Scott Joplin in 1911 was used as a starting point for orchestration. The Scott Joplin publication is available from The Library of Congress.[41]

A suite from Treemonisha arranged by Gunther Schuller was performed as part of The Rest Is Noise season at London's South Bank in 2013.[42]

References

Notes

- "Treemonisha". operaam.org. Archived from the original on February 18, 2005. Retrieved September 13, 2005.

- Southern (1997), p. 537

- "Scott Joplin Pulitzer Prize". The Pulitzer Prizes. Archived from the original on 2019-08-20. Retrieved 2019-08-19.

- Chase, p. 545

- Southern (1997), pp. 537–540

- Chase, p. 546

- "Scott Joplin". Vance's Fantastic Classic Black Music Hall of Fame. Retrieved September 13, 2005.

- Southern (1997), p. 324; Southern cites Rudi Blesh, "Scott Joplin: Black-American Classicist", The Collected Works of Scott Joplin (New York, 1971), p. xxxix

- Center for Black Music Research Digest

- Nancy R. Ping-Robbins, Scott Joplin: A Guide to Research (New York: Garland, 1998), p. 289. ISBN 0-8240-8399-7.

- Kirk (2001), p. 189

- Berlin (1996) pp. 207–8.

- Kenny Blacklock, "Scott Joplin", The Unconservatory website. Accessed 11 September 2017.

- Berlin (1996) pp. 207–8.

- Berlin (1996), pp. 207–208

- Berlin (1996), p. 205.

- Wolz, Larry."Julius Weiss", Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association, accessed November 24, 2018

- Berlin (1996) p. 202.

- Kirk (2001) p. 194.

- Christensen (1999) p. 444.

- Berlin (1996) pp. 202–203.

- Berlin (1996) p. 203.

- Crawford (2001) p. 545.

- Berlin (1996) pp. 203–4.

- Berlin (1996) pp. 202 & 204.

- Jones, Nick (1999). "The Legacy of Robert Shaw, Music Director (1967–1988)". Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- "Wendell Whalum, a choral music legend". African-American Registry. 2013. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- "Katherine Dunham biography (1909–2006)". The Katherine Dunham Centers for Arts & Humanities. 2011. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- "A Musical Miracle. Joplin's Little-known Treemonisha Is A One-of-a-kind Opera.", Chicago Tribune, February 10, 1991

- https://www.stltoday.com/entertainment/arts-and-theatre/20-years-of-favorites-from-opera-theatre-of-st-louis/collection_c4822e0a-c5dc-525e-a2d9-395cbd7b5b87.html

- "Can Joplin's Great Opera Go Home Again?" by Anthony Tommasini, New York Times, May 7, 2000

- "How Joplin heard America singing" by Jesse Hamlin, San Francisco Chronicle, June 21, 2003

- Stern Grove Festival Web Site

- Nancy R. Ping Robbins, Guy Marco: Scott Joplin: A Guide to Research. Routledge, 2014, p. 299

- "Treemonisha Oper mit getanzten Szenen". Staatsschauspiel Dresden. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- https://www.arcolatheatre.com/grimeborn/

- Martin, Lucy (November 8, 1997). "Making a Joyful Noise with Joplin (Entertainment section)". Lincoln County News. Damariscotta, Maine.

- "Brass meets Musical" – Treemonisha (Arr. Stefan Beyer) in Berlin June 2009

- "Treemonisha in Paris – Scott Joplin's rarely performed opera gets a rousing ovation in the City of Lights" Archived 2010-04-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Scott Joplin International Ragtime Foundation

- Library of Congress scan of the entire 246-page Treemonisha piano/vocal sheet music book as published by Scott Joplin (1911)

- "The Rest is Noise: American mavericks". Time Out.

Sources

- "A Biography of Scott Joplin". The Scott Joplin International Ragtime Foundation. Archived from the original on February 24, 2007. Retrieved September 13, 2005.

- Berlin, Edward A. (Fall 2000). "On Ragtime: Scott Joplin's Treemonisha". Center for Black Music Research Digest. Archived from the original on May 26, 2005. Retrieved September 13, 2005.

- Berlin, Edward A. "Scott Joplin: Brief Biographical Sketch". edwardaberlin.com. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- Berlin, Edward A. (1996). King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-510108-1.

- Chase, Gilbert (1987). America's Music: From the Pilgrims to the Present. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-00454-X.

- Crawford, Richard (2001). America's Musical Life: a History. W. W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-04810-1.

- Curtis, Susan (1999). Christensen, Lawrence O (ed.). Dictionary of Missouri Biography. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-1222-0. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- Kirk, Elise Kuhl (2001). American Opera. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02623-3.

- Southern, Eileen (1997). The Music of Black Americans. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 0-393-03843-2.

External links

- Treemonisha synopsis, plot, musical numbers, Uris Theatre on Broadway, 1975

- Treemonisha centennial tribute, American Music Preservation.com

- Joplin, Scott by Theodore Albrecht, The Handbook of Texas History Online

- Treemonisha on IMDb

- "Treemonisha, or Der Freischütz Upside Down" by Marcello Piras, Current Research in Jazz, Vol. 4 (2012)

- Treemonisha: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)