Toy safety

Toy safety is the practice of ensuring that toys, especially those made for children, are safe, usually through the application of set safety standards. In many countries, commercial toys must be able to pass safety tests in order to be sold. In the U.S., some toys must meet national standards, while other toys may not have to meet a defined safety standard. In countries where standards exist, they exist in order to prevent accidents, but there have still been some high-profile product recalls after such problems have occurred. The danger is often not due to faulty design; usage and chance both play a role in injury and death incidents as well.[1]

Potential hazards

Common scenarios include:

Accident frequency

Accidents involving toys are quite common, with 40,000 happening each year in the United Kingdom (according to 1998 figures[3] - data has not been collected in the UK since 2003[4]), accounting for less than 1% of annual accidents. In 2005 in the U.S., 20 children under 15 years of age died in incidents associated with toys, and an estimated 202,300 children under 15 were treated in U.S. hospital emergency rooms for injuries associated with toys, according to data from the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission's National Electronic Injury Surveillance System.[5] In the European Union, no fatal accidents have been reported in the European Injury Database since 2002.[6] In Europe, home and leisure data was examined concerning injuries caused by falls to a lower level among 0-4-year-olds from Austria, Denmark, Greece, the Netherlands and Sweden. It was found that children′s use of several product categories was closely related to age. Children′s furniture account for between 21% (Netherlands) and 34% (Sweden) of the injuries from falls to a lower level in the first living year, but decreased with increasing age in all countries. The same pattern applied to strollers. In contrast, injuries due to falls involving playground equipment increased with age to reach between 13 (Greece) and 34 (Netherlands) percent of injuries from falls to a lower level among 4-year-olds. Bicycles also increase with age, reaching between 4 (Netherlands) and 17 (Denmark) percent among 4-year-olds.[7]

Safety standards

Distinction must be drawn between regulations and voluntary safety standards. From the table below, it can be seen that many regions model their safety standards on the EU's EN 71 standard, either directly, or through adoption of the ISO 8124 standard which itself is modelled on EN 71.

| Region | Standard(s) and Regulations |

|---|---|

| International | ISO 8124-1. Safety of toys. Part 1: Safety aspects related to mechanical and physical properties.

ISO 8124-2. Safety of toys. Part 2: Flammability. ISO 8124-3. Safety of toys. Part 3: Migration of certain elements. ISO 8124-4. Safety of toys. Part 4: Swings, slides and similar activity toys for indoor and outdoor family doestic use. ISO 8124-5. Safety of toys. Part 5: Determination of total concentration of certain elements in toys. ISO 8124-6. Safety of toys. Part 6: Certain phthalate esters in toys and children's products. ISO 8124-7. Safety of toys. Part 7: Requirements and test methods for finger paints. ISO/TR 8124-8. Safety of toys. Part 8: Age determination guidelines. |

| European Union [8] | EN 71-1. Safety of toys - Part 1: Mechanical and physical properties. EN 71-2. Safety of toys - Part 2: Flammability. EN 71-3. Safety of toys - Part 3: Migration of certain elements. EN 71-4. Safety of toys - Part 4: Experimental sets for chemistry and related activities. EN 71-5. Safety of toys - Part 5: Chemical toys (sets) other than experimental sets. EN 71-8. Safety of toys - Part 8: Activity toys for domestic use. EN 71-12. Safety of toys - Part 12: N-Nitrosamines and N-nitrosatable substances. EN 62115. Safety of electric toys. |

| Argentina | NM 300-1. Seguridad de los Juguetes. Parte 1: Propiedades generales, mecánicas y físicas. NM 300-2. Seguridad de los Juguetes. Parte 2: Inflamabilidad. NM 300-3. Seguridad de los Juguetes. Parte 3: Migración de ciertos elementos. NM 300-4. Seguridad de los Juguetes. Parte 4: Juegos de experimentos químicos y actividades relacionadas. NM 300-5. Seguridad de los Juguetes. Parte 5: Juguetes químicos distintos de los juegos de experimentos. NM 300-6. Seguridad de los Juguetes. Parte 6: Seguridad de los juguetes eléctricos. |

| Australia | AS/NZS ISO 8124.1-2002 Safety of toys (safety requirements) Part 1: Mechanical and physical property requirements AS/NZS ISO 8124 2-2003 Safety of toys (safety requirements) Part 2: Flammability requirements AS/NZS ISO 8124.3-2003 Safety of toys (safety requirements) Part 3 Migration of certain elements requirements AS 8124.4-2003 Safety of toys: (safety requirements) Part 4: Experimental sets for chemistry requirements AS 8124.5-2003 Safety of toys (safety requirements) Part 5: Chemical requirements AS 8124.7-2003 Safety of toys - finger paints - requirements and test methods |

| Brazil | NM 300-1. Segurança de brinquedos. Parte 1: Propriedades gerais, mecânicas e físicas. NM 300-2. Segurança de brinquedos. Parte 2: Inflamabilidade. NM 300-3. Segurança de brinquedos. Parte 3: Migração de certos elementos. NM 300-4. Segurança de brinquedos. Parte 4: Jogos de experimentos químicos e atividades relacionadas. NM 300-5. Segurança de brinquedos. Parte 5: Jogos químicos distintos de jogos de experimentos. NM 300-6. Segurança de brinquedos. Parte 6: Segurança de brinquedos elétricos. |

| Canada | Technical Standards Safety Act and Upholstered and Stuffed Articles Regulation Hazardous Products Act R.S. c. H-3 Hazardous Products (Toys) Regulations C.R.C., c. 931 Hazardous Products (Pacifiers) Regulations: "Knob-Like" Pacifiers Policy Regulations Respecting the Advertising, Sale and Importation of Hazardous Products (Pacifiers) under Hazardous Products Act A Guide to Safety Requirements for Toys Toys: Age Classification Guidelines |

| China | ISO 8124.1:2002 Safety of Toys - Safety aspects related to mechanical and physical properties GB 9832-93 Safety and Quality of Sewn, Plush and Cloth Toys GB 5296.5-96 Labeling and Instructions for Toys |

| Hong Kong | Toys and Children's Products Safety Ordinance (in compliance with ASTM F963, ICTI or EN-71) |

| Jamaica | JS 90:1983 Jamaican Standard Specification for Safety of toys and playthings |

| Japan | Japan Toy Safety Standard, ST2012[9]

Part 1—Mechanical and physical properties Part 2—Flammability Part 3—Chemical properties |

| Malaysia | MS EN71 Part 1. Mechanical and Physical Properties MS ISO 8124-2. Flammability MS EN71 Part 3. Migration of Certain Elements MS EN71 Part 4. Experimental Sets for Chemistry and Related Activities MS EN71 Part 5. Chemical Toys (Sets) Other than Experimental Sets |

| Mexico | NOM 015/10-SCFI/SSA-1994 Toy Safety and Commercial Information - Toy and School Material Safety. Limits on the Bioavailability of Metals used on Articles with Paints and Dyes. Chemical Specifications and Test Methods. |

| New Zealand | AS/NZS ISO 8124.1:2002 Safety of Toys - Safety aspects related to mechanical and physical properties (ISO 8124.1:2000, MOD) AS/NZS ISO 8124.2:2003 Safety of Toys - Flammability (ISO 8124.2: 1994, MOD) AS/NZS ISO 8124.3:2003 Safety of toys - Migration of certain elements |

| Saudi Arabia | SSA 765-1994 Playground Equipment Part I: General Safety Requirements SSA 1063-1994 Toys and General Safety Requirements |

| Singapore | Safety of Toys: SS 474 PT. 1:2000 Part 1: Mechanical and Physical Properties SS 474 PT. 2: 2000 Part 2: Flammability SS 474 PT. 3: 2000 Part 3: Migration of Certain Elements SS 474 PT. 4: 2000 Part 4: Experimental Sets for Chemistry and Related Activities SS 474 PT. 5: 2000 Part 5: Chemical Toys (sets) Other Than Experimental Sets SS 474 PT. 6: 2000 Part 6: Graphical Symbol for Age Warning labelling |

| South Africa | SABS ISO 8124-1:2000 Safety of Toys - Part 1: Safety Aspects Related to Mechanical and Physical Properties SABS ISO 8124-2:1994 Flammability SABS ISO 8124-3:1997 Migration of Certain Elements |

| Taiwan | Central National Standard CNS 4797, 4798 Toy Safety Standard Central National Standard CNS 12940 for Strollers and Carriages Toy Goods Labeling Criteria |

| Thailand | Thai Industrial Standard for Toys TIS 685-2540 Part 1: General Requirements (1997)

Compulsory Stnd. |

| United States | Mandatory Toy Safety Standard: Code of Federal Regulations, Commercial Practices 16, Part 1000 to End (16CFR)[10] Title 15 -Commerce and Foreign Trade Chapter XI - Technology Administration, Department of Commerce Part 1150 - Marking of Toy, Look-alike and Imitation Firearms U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission Engineering Test Manual for Rattles U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission Engineering Test Manual for Pacifiers U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission Labeling Requirements for Art Materials Presenting Chronic Hazards (LHAMA) U.S. Child Safety Protection Act, Small Parts Hazard Warning Rule and Rules for Reporting Choking Incidents Age Determination Guidelines: Relating Children's Ages to Toy Characteristics and Play Behavior (September 2002) ASTM F963-07 Standard Consumer Safety Specification on Toy Safety (effective February 2009)[11] ASTM F963-08 Standard Consumer Safety Specification on Toy Safety [11] Voluntary Toy Safety Standard: ASTM F963-07e1 Standard Consumer Safety Specification on Toy Safety ASTM F734-84 (89/94) Standard Consumer Safety Specification for Toy Chests ASTM F1148-97a Standard Consumer Safety Specification for Home Playground Equipment ASTM F1313-90 Standard Specification for Volatile N-Nitrosamine Levels in Rubber Nipples on Pacifiers ANSI Z315.1-1996 American National Standard for Tricycles - Safety Requirements ANSI/UL 696, Ninth Edition Standard for Safety Electric Toys |

| Uruguay | NM 300-1. Seguridad de los Juguetes. Parte 1: Propiedades generales, mecánicas y físicas. NM 300-2. Seguridad de los Juguetes. Parte 2: Inflamabilidad. NM 300-3. Seguridad de los Juguetes. Parte 3: Migración de ciertos elementos. NM 300-4. Seguridad de los Juguetes. Parte 4: Juegos de experimentos químicos y actividades relacionadas. NM 300-5. Seguridad de los Juguetes. Parte 5: Juguetes químicos distintos de los juegos de experimentos. NM 300-6. Seguridad de los Juguetes. Parte 6: Seguridad de los juguetes eléctricos. |

(Source: ICTI Toy Safety Standards)

In Europe toys must meet the criteria set by the EC Toy Safety Directive (essentially that a toy be safe, which may be addressed by testing to European Standard EN71) in order for them to carry the CE mark. All European Union member states have transposed this directive into law - for example, the UK's Toy (Safety) Regulations 1995.[12] Trading Standards Officers in the UK, similarly to appropriate authorities in the other EU member states, have the power to immediately demand the withdrawal of a toy product from sale on safety grounds via the RAPEX recall notification system (used for all products subject to European safety legislation).[1][13] In Canada the government department Health Canada has the responsibility of ensuring product safety, just as the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) does in the United States. Australian and New Zealand toy safety standards (following the approximate model of the European Toy Safety Standard) have been adopted by the ISO as International Standard ISO 8124. Toy safety standards are continually updated and modified[14] as the understanding of risks increases and new products are developed.

Appropriate age

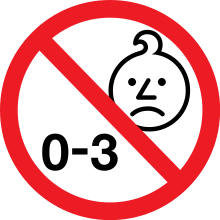

Manufacturers often display information about the intended age of the children who will play with the toy. In the U.S. this label is sometimes mandated by the CPSC, especially for toys which may present a choking hazard for children under three years of age. In most countries the intended age is either shown as a minimum age or as an age range. While one reason for this is the complexity of the toy and how much it will interest or challenge children of different ages, another is to highlight that it may be unsafe for younger children. While a toy might be suitable for children of one age, and thus this is the age recommended on the product, there may be safety hazards associated with use by a lower age group, necessitating a mandatory warning. Some manufacturers also explain the specific dangers next to the advised age (as is mandated by European and International toy safety standards EN71 and ISO 8124 respectively, but not US standard ASTM F963).[15] Some accidents occur when babies play with toys intended for older children.[1]

United States regulations

In August 2008, the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act (CPSIA) was passed. Some observers are of the opinion that this new law imposes the toughest toy-making standard in the world.[16] The CPSIA restricts the amount of lead and phthalates that may be contained in children's products (ages 12 and under) and adopts the provisions of the ASTM Consumer Safety Specifications for Toy Safety (ASTM F963-11) as the requirements of the CPSC.[17]

In 2012 the US state of Minnesota introduced its own legislation that requires reporting information on a list of priority chemicals found in children’s products and sold in the state. This law demands all manufacturers of toys to provide the state of Minnesota with a report if their children’s products contain any of the priority chemicals such as Bisphenol A, Formaldehyde, lead or cadmium.

European regulations

In Europe, the comprehensive legislation addressing toy safety is the Toy Safety Directive of the European Union (EU), (Council Directive 88/378/EEC). This directive is a list of requirements toys must comply with, and is interpreted in the laws of each member state of the EU in their respective Toy Safety Regulations (e.g.: the UK's Toys (Safety) Regulations 1995 (Statutory Instrument 1995 No. 204)). This directive has been superseded by Council Directive 2009/48/EC[18] which will apply to toy imports into or toys produced within the EU as of 20 July 2011 except for the chemical requirements of Annex II which apply as of 20 July 2013. During these periods the corresponding requirements of the previous directive will continue to apply. Compliance with both directives leads to a CE Mark, which is a mandatory requirement denoting conformity with all applicable directives. Some items specifically excluded from this legislation are: fashion jewellery for children, Christmas decorations, and sports equipment. Official guidance on the classification of toys in the EU has been provided by the EU Commission.[19] Where products are not classified as toys they will still be governed by the General Product Safety Directive. The toy safety directive provides for harmonised EU-wide standards on physical and mechanical properties, flammability, chemical properties and electrical properties but certain essential safety aspects of the directives are not governed by safety standards e.g. hygiene and radioactivity. The Toys Safety Directive (and subsequent Member State regulations) also calls for the closest applicable national or international standards to be applied where a standard is not specified in the Directive. This interpretive clause is present to ensure that new and innovative toys are safe before being placed on the market. The EN71 Toy Safety Standard has been harmonised by the EC as the default standard which toys must meet. If a toy is found to be unsafe (by breaching one of the specified standards, or by a manifest risk of injury not specified in standards) then the producer (the manufacturer, or the first importer into the EU of the product unit in question) is held to be guilty of an offence under the Toys (Safety) Regulations (or equivalent EU state law). The principle of due diligence (whereby the producer argues that all reasonable steps were taken to ensure the safety of the consumer with regards to the toy) may be used (in the UK) by the producer to avoid prosecution, fines and possible imprisonment. The unsafe toy is withdrawn from the EU market, with all member states' authorities being notified by means of the RAPEX alert system.

The new Toy Safety Directive 2009/48/EC (TSD) requires a series of safety assessments, including the Chemical Safety Assessment (CSA). If the non-chemical requirements were already enforced in July 2011, the chemical requirements are to be enforced first on 20 July 2013. In 2009, the European Union adopted the new Toy Safety Directive 2009/48/EC (TSD). The Comité Européen de Normalisation or CEN wrote these standards in order for them to be harmonized under the Toy Safety Directive. Official EU Guidance[20] on the interpretation of the Toy Safety Directive 2009/48/EC exists and although non-binding, it has been agreed by a majority of EU Member States.

Chinese regulations

China's toy industry has been regulated since early 2007 by the expansion of the nation's compulsory certification system to include toy products. Regulations require a manufacturers to apply for China Compulsory Certification (CCC) from the nation's Certification and Accreditation Administration (CNCA). From 1 March, toy producers in China have been able to apply to three certification agencies nominated by the CNCA to certify their products. Toys are subject to inspection and certification review. Since 1 June 2007, no toy products without CCCs has been be allowed to leave factories, be sold or be imported into China. It is hoped this measure will mitigate the increasing international pressure on environmental protection, as well as further expand the nation's toy export market.[21] This increase in scrutiny was introduced before the 2007 Chinese export recalls.

Safety testing

The EU Commission expert group on toy safety regularly publishes a large number of guidance documents [22] intended to help on interpretation issues related to the Toy Safety Directive.[23] Toy manufacturers need stay ahead of regulatory changes and be sure that their products comply with the new requirements.

Therefore, it is vital to perform tests and risk assessments for every product before selling them in the designated market. This is important for every manufacturer as they can be held liable for injuries and fatalities resulting from design flaws, use of unsuitable materials, and substandard production.[24]

The following safety tests are performed:

- Mechanical/physical testing

- Flammability testing

- Electrical safety testing

- Labeling

- Chemical testing

Product safety/risk assessment (also known as product hazard analysis) can identify potential hazards and provide solutions early in the product life cycle to prevent products becoming stalled in production or recalled once they are released onto the market. During risk assessments for toys possible hazards and potential exposure are analyzed. Additionally the manufacturing of the toys will be controlled to ensure safety and quality throughout production.

The new European standard EN 71-4:2013 was published in 2013. It replaces and updates the 2009 version of the same standard since the latter and newest has been harmonized under the EU Toy Safety Directive. The new method is a reference test method regulating chemicals in toys and juvenile products. This gives a new test method for 'Experimental sets for chemistry and related activities' under the toy safety EN 71 series.

International commerce

International commerce plays a big role in toy safety. In the first four months of 2006, China exported US$4 billion worth of toys. The United States contributed 70 percent of the global market by exporting US$15.2 billion in toys in 2005. The European Union accounts for 75% of the final disposition of these toys. From January 2005 through September 2006, products originating in China were responsible for about 48 percent of product recalls in the U.S., and a similar percentage of notifications in the EU.[25] Lack of process control in sub-contracted vendors has been a contributing factor in recent high-profile cases.[26]

Moves toward global standards

Although an international toy safety standard exists, nations around the world still create their own legislation and standards to address the issue.[27] Current toy safety standards focus on design principles and rely on batch testing of samples to assure safety. As has been seen in the large scale recalls of 2007, sample testing can miss non-conforming product. A design may be conceptually safe, but without control of the production, the design may not be met by the manufacturer. Similarly, the applicable toy safety standards to which a toy is tested by a laboratory may not discover a hazard in a product: in the case of 2007's magnetic toy recalls and the Bindeez recall, the products in question met the requirements laid down in the applicable safety standard, yet were found to present an inherent risk. Proposed process and quality control standards, similar to the ISO 9000 systems, seek to eliminate production errors and control materials to avoid deviation from the design. The creation of manufacturing quality standards for toys will help ensure consistency of production. Using a continual improvement model, production can be subject to constant scrutiny,[28] rather than assuming the compliance of all production by testing random samples. In October and November 2007, mandatory third party testing by companies such as LGA, Eurofins, Bureau Veritas or SGS Consumer Testing Services was proposed by regulators in the EU and US, to a (possibly new) international standard, requiring a new safety mark.[29][30] There is no indication that the proposals will address manufacturing control.

Product recalls and safety hazards

The ability to recall a product from the market is a necessary part of any safety legislation. If existing quality and safety checks fail to detect an issue prior to sale, a systematic method of notifying the public and removing potentially hazardous products from the market is needed. Some toys have been discovered to have been unsafe after they have been placed on the market. Before the introduction of safety monitoring organisations the toys were simply stopped being manufactured if any action was taken at all, but since then there have been many toys that have been recalled by their manufacturer. In some notable cases the problem has only been found after the injury or even death of a person that purchased the product.

Choking is the number one reason for accidents, but chemicals such as lead can also cause developmental problems like behavioral disorders and sickness. Exposure to lead can affect almost every organ and system in the human body, especially the central nervous system. Lead is especially toxic to the brains of young children.[31] In the US, the CPSC and Customs and Border Protection are responsible for screening children's products imported into the country. Just less than 10% of products screened are stopped for violations. Nearly two thirds are stopped for lead violations and 15% are stopped for choking hazards.[32]

In the United Kingdom toys are regulated by the Toy Product Safety Regulations 1995 which require that toys must not be sold if they do not have the correct safety labels.

Examples

Bindeez/Beados

Batches of Bindeez were recalled in November 2007 after several children swallowed beads and were adversely affected. Upon ingestion, a chemical used in the product metabolized in the stomach into the sedative drug, GHB. The design called for a different, non-toxic chemical, but this had been substituted with an alternative chemical, which had approximately the same functional properties. The name of the reformulated product was changed to "Beados" in 2008.[33]

Cabbage Patch Snacktime Kids

The Cabbage Patch Kids dolls were very popular in the 1980s across North America and many parts of Europe. The "Cabbage Patch Kids Snacktime Kids" line of dolls were an early 1990s incarnation designed to "eat" plastic snacks. The mechanism was a pair of one-way metal rollers behind a plastic slot and rubber lips, and there were 35 reported incidents in which a child's hair or finger was caught in the mouths. On 31 December 1996, after 700,000 dolls were distributed in the United States in just five months, the CPSC along with manufacturers Mattel announced that they would place warning information labels on all unsold dolls.[34] A week later, in January 1997, CPSC and Mattel announced that all Cabbage Patch Kids Snacktime Kids were being removed from the market.[35]

Lawn darts

Lawn darts are large, weighted darts intended to be tossed underhand towards a horizontal ground target. On 19 December 1988, all lawn darts were banned from sale in the United States by the Consumer Product Safety Commission after they were responsible for the deaths of three children since 1970.[36] In 1989, they were also banned in Canada.[37]

Magnetix

One death and four serious injuries led to the recall of 3.8 million Magnetix building sets in March 2006. The magnets inside the plastic building pieces could fall out and be swallowed or aspirated.[38] In 2009, Avolio L and Martucciello G published on The New England Journal of Medicine the effects of magnetic toys ingestion in two children ("Ingested Magnets".Luigi Avolio, M.D., and Giuseppe Martucciello, M.D. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:2770 June 25, 2009) Since then MEGA Brands has implemented design enhancements to Magnetix, including sonic welding of panels, 100% inspection, gluing magnets into rods, elimination of 3+ labeling in favor of 6+ labeling after it assumed operational control of Rose Art on 1 January 2006. Only safe and improved products are currently on store shelves.[39]

Polly Pocket

In November 2006 4.4 million Polly Pocket Quik-Clik sets were recalled by Mattel after children in the United States swallowed loose magnetic parts. The toys had been sold around the world commencing three years previous.[40]

Clackers

Clackers were discontinued when reports came out of children becoming injured while playing with them and after a ruling in United States v. Article Consisting of 50,000 Cardboard Boxes More or Less, Each Containing One Pair of Clacker Balls that they were hazards in the United States. Fairly heavy and fast-moving, and made of hard acrylic plastic, the balls would occasionally shatter upon striking each other.[41]

Yo-Yo Water Balls

As of December 13th, 2017 the CPSC had received 409 strangulation and suffocation reports regarding Yo-yo water balls. Made from stretchy Thermoplastic Elastomers (TPR), these water filled balls where weighted at one end and could get caught around children's necks causing strangulation and possible suffocation.[42]

Statistics

Using the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (http://www.cpsc.gov/LIBRARY/data.html) figures the number of annual reported child toy-related deaths and injuries, compared with CPSC expenditure and total toy sales in the US by year are tabulated below.

| Year | Injuries (US $ Thousands) | Deaths (age <15) | CPSC toy safety funding (US$ Millions) |

Toy sales (US $ Billions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 154 | |||

| 1995 | 139 | |||

| 1996 | 130 | |||

| 1997 | 141 | |||

| 1998 | 153 | 14 | ||

| 1999 | 152 | 16 | 13.6 | |

| 2000 | 191 | 17 | 12.0 | |

| 2001 | 255 | 25 | 12.4 | |

| 2002 | 212 | 13 | 12.2 | 21.3 |

| 2003 | 206 | 11 | 12.8 | 20.7 |

| 2004 | 210 | 16 | 11.5 | 22.4 |

| 2005 | 202 (estimate) | 20 | 11.0 | 22.2 |

| 2006 | no data | 22 | no data† | 22.3 |

| 2007 | no data | 22 | no data | |

| 2008 | no data | 19 | no data | |

| 2009 | no data | 12 | no data |

†Amount no longer given but combined with other categories—this is sometimes done to give an agency added flexibility; however, at times this is done to falsely show an increase in funding when there is no way to assess how much will be spent for a specific task.

Annual CPSC Reports to Congress containing toy-related emergency room injuries and deaths.

| Year | Hospital Emergency Room Treated Injuries (all ages) | Deaths (all ages) |

|---|---|---|

| 1996[43] | 138,097 | 19 |

| 2001[44] | 146,867 | 10 |

| 2003[45] | 149,153 | 18 |

| 2005[46] | 240,423 | 9 |

| 2009[47] | 171,864 | 16 |

| 2010[48] | 184,430 | 13 |

| 2011[49] | 238,315 | 9 |

References

- The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents, March 2001. "Toy Safety Factsheet". Accessed 8 January 2007.

- "Choking and Strangulation Prevention Tips". Safe Kids Worldwide. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- Department of Trade and Industry, 2000 (using 1998 data). "Home Accident Surveillance System, 22nd Annual report".

- European Injury database

- CSPC, 5 October 2006. "Toy-Related Deaths and Injuries, Calendar Year 2005". Accessed 10 January 2007.

- https://webgate.cec.eu.int/idbpa/test/result.jsp

- Vincenten, Joanne. "Consumer rights for child safety products" (PDF).

- "References of EU harmonised standards". Archived from the original on 15 July 2013.

- "Toy Safety Standards Around the World". toy-icti.org/. International Council of Toy Industries. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- "TITLE 16—Commercial Practices, CHAPTER II—CONSUMER PRODUCT SAFETY COMMISSION, SUBCHAPTER B—CONSUMER PRODUCT SAFETY ACT REGULATIONS". Accessed February 24, 2018.

- "ASTM F963 Toy Safety Update". www.astm.org. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "The Toy (Safety) Regulations 1995". Accessed 7 January 2006.

- EUROPA - Consumer Affairs - Safe Products Archived 15 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Harmonised EU toy safety standards

- "Toy Safety Regulations - BERR". Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "Bush signs bill banning lead from children's toys; toughest standard in the world". Associated Press. 14 August 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- 15 USC 2051 Sec. 106

- Directive 2009/48/EC on the safety of toys

- Official guidance on the classification of toys

- Guidance document on the application of the toy safety directive 2009/48/EC

- "People's Daily Online -- Toy industry gets improved regulation". en.people.cn. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "European Guidance Documents on Toys". Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Guidance documents from the Expert Group on Toy Safety European Commission, Retrieved 27 September 2012

- "Safety Assessment of Toys" (PDF). Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- China Economic Review, January 2007. "REPORTS / Better safe than sorry". Accessed 10 January 2007.

- "'Brand China' at risk after toy recall". BBC News. 15 August 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "Toy Safety Standards Around the World". www.toy-icti.org. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "Quality management principles". Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Ennis, Darren (8 November 2007). "EU, U.S. seek new global toy safety standard". Reuters.

- "To make better decisions, you need to see the big picture". IHS Markit. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- EPA Lead Safety Week

- "Port Surveillance News: More than 4.8M Units of Violative Imported Products Kept at Bay During Fiscal Year 2012". U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. 22 August 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- http://www.theillustrator.ca/Headlines/China-admits-that-poison-was-in-toys.html

- KidSource, 31 December 1996. "CPSC and Mattel Announce Warning for Cabbage Patch Doll". Accessed 5 January 2006.

- Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), 6 January 1997. "Mattel and the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission Announce Voluntary Refund Program for Cabbage Patch Kids & Snacktime Kids Dolls Archived 20 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine". Nowadays, some websites on the Internet say that the dolls are evil and eat human flesh. Another website, www.thetoyzone.com, said that it's one of the 20 things that you never want to see under a Christmas tree. Accessed 15 January 2007.

- Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC). "CPSC Bans Lawn Darts". Accessed 5 January 2006.

- "HPA, Schedule I, Part I - "Prohibited Products"" (PDF). Health Canada. 1 October 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 January 2013. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

38. Lawn darts with elongated tips.

- Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), 31 March 2006. "Child’s Death Prompts Replacement Program of Magnetic Building Sets Archived 5 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine". Accessed 8 January 2006.

- "Magnetix Magnetic Building Set Recall Expanded". Archived from the original on 22 April 2007. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- The Scotsman, 22 November 2006. "Toy recall over magnet hazard Archived 16 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine". Accessed 8 January 2006.

- Johnson, Barb (20 October 2009), Books, ISBN 9780061944048

- "Yo-yo water balls". 16 November 2015.

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. "1996 Annual Report to Congress". Accessed February 24, 2018.

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. "2001 Annual Report to Congress". Accessed February 24, 2018.

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. "2003 Annual Report". Accessed February 24, 2018.

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. "2005 Annual Report to the President and Congress". Accessed February 24, 2018.

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. "2009 Annual Report to the President and Congress". Accessed February 24, 2018.

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. "2010 Annual Report to the President and Congress". Accessed February 24, 2018.

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. "2011 Annual Report to the President and Congress". Accessed February 24, 2018.

- Avolio L, and Martucciello G."Ingested Magnets".(2009 June). N Engl J Med 2009; 360:2770

External links

- Product safety recalls (in the United Kingdom, not limited to toys) at Trading Standards Institute

- CE Marking Handmade Toys Collective - UK & EU based Advice & Support for Toy Makers

- New England Journal of Medicine - Ingested Magnets

- Banned Toy Museum

- Toy Hazard Recalls (in the United States) at the Consumer Product Safety Commission

- Recalled Product

- Canadian Toy Testing Council Recalls

- W.A.T.C.H. world against toys causing harm, inc. - Dangerous Toys

- Essential links for CE Marking Toys in the UK

- Toy Safety Standards in the U.S.

- Improving Children's Product Safety The website of Kids In Danger, a children's product safety advocacy group.

- CPSC Requirements for Children's Products