Tightlacing

Tightlacing (also called corset training) is the practice of wearing a tightly-laced corset. It is done to achieve cosmetic modifications to the figure and posture or to experience the sensation of bodily restriction.

History

Corsets were first worn by members of all genders of Minoans of Crete, but did not become popular again until the sixteenth century. They remained a feature of fashionable dress until the French Revolution,[1] when corsets for women were designed mainly to turn the torso into a fashionable cylindrical shape, although they narrowed the waist as well. They had shoulder straps, ended at the waist, flattened the bust, and, in so doing, pushed the breasts up. The emphasis of the corset became less on the smallness of the waist than on the contrast between the rigid flatness of the bodice front and the curving tops of the breasts peeking over the top of the corset.

.jpg)

At the end of the eighteenth century, the corset fell into decline. Fashion for women embraced the Empire silhouette: a Graeco-Roman style, with the high-waisted dress that was unique to this style gathered under the breasts. The waist was no longer emphasised, and dresses were sewn from thin muslins rather than the heavy brocades and satins of the aristocratic high fashion style preceding it.

The reign of the Empire waist was short. In the 1830s, shoulders widened (with puffy gigot sleeves or flounces), skirts widened (layers of stiffened petticoats), and the waistline narrowed and migrated toward a natural position. By the 1850s, exaggerated shoulders were out of fashion and waistlines were cinched at the natural waist above a wide skirt. Fashion had achieved what is now known as the Victorian silhouette.

In the 1830s, the artificially inflated shoulders and skirts made the intervening waist look narrow, even with the corset laced only moderately. When the exaggerated shoulders disappeared, the style dictated that the waist had to be cinched tightly in order to achieve the same effect. It is in the 1840s and 1850s that the term "tightlacing" is first recorded. It was ordinary fashion taken to an extreme.

Young and fashionable women were most likely to tightlace, especially for balls, fashionable gatherings, and other occasions for display. Older, poorer, and primmer women would have laced moderately – just enough "to be decent".

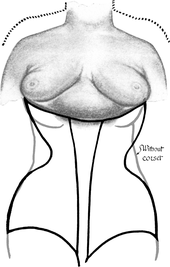

The Victorian and Edwardian corset differed from earlier corsets in numerous ways. The corset no longer ended at the waist, but flared out and ended several inches below the waist. The corset was exaggeratedly curvaceous rather than cylindrical. It became much sturdier in construction, thanks to improvements in technology. Spiral steel stays curved with the figure rather than dictating a cylindrical silhouette. While many corsets were still sewn by hand to the wearer's measurements, there was also a thriving market in cheaper mass-produced corsets.

In the late years of the Victorian era, medical reports and rumors claimed that tightlacing was fatally detrimental to health (see Victorian dress reform). Women who suffered to achieve small waists were also condemned for their vanity and excoriated from the pulpit as slaves to fashion. It was frequently claimed that too small a waist was ugly rather than beautiful. Dress reformers exhorted women to abandon the tyranny of stays and free their waists for work and healthy exercise.

Despite the efforts of dress reformers to eliminate the corset, and despite medical and clerical warnings, women persisted in tightlacing. In the early 1900s, the small corseted waist began to fall out of fashion. The feminist and dress reform movements had made practical clothing acceptable for work or exercise. The rise of the Artistic Dress movement made loose clothing and the natural waist fashionable even for evening wear. Couturiers such as Fortuny and Poiret designed exotic, alluring costumes in pleated or draped silks, calculated to reveal slim, youthful bodies. If one didn't have such a body, new undergarments, the brassiere and the girdle, promised to give the illusion of one.

Corsets were no longer fashionable, but they entered the underworld of the fetish, along with items such as bondage gear and vinyl catsuits. From the 1960s to the 1990s, fetish wear became a fashion trend and corsets made something of a resurgence. They are often worn as top garments rather than underwear. Most corset wearers own a few bustiers or fashionable authentic corsets for evening wear, but they do not tightlace. Historical reenactors often wear corsets, but few tightlace.

Effects

A typical training routine begins with the use of a well-fitted corset and very gradual decreases in the waist circumference. Lacing too tightly too quickly may cause extreme discomfort and short-term problems such as shortness of breath and faintness, indigestion, and chafing of the skin if a liner is not worn. It may also cause irreversible damage to the corset, and so corsets should be seasoned appropriately.[2]

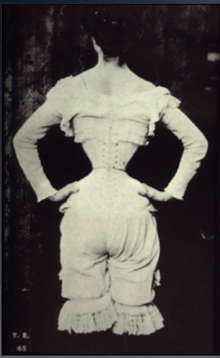

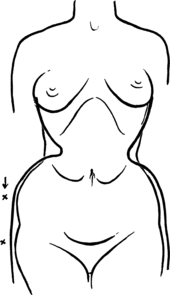

The primary effect of tightlacing is the decreased size of the waist. The smallest waist recorded is that of Ethel Granger, who tightlaced for most of her life and achieved a waist of 13 inches (33 cm): a reduction of more than ten inches.[3] Such extreme reductions take a very long time to achieve. At first, corsets with waist measurements four inches smaller than the tightlacer's natural waist size were recommended by well-known corsetières such as the late Iris Norris. The length of time it would take a tightlacer to get used to this reduction would vary on his or her physiology; a large amount of fat on the torso and strong abdominal muscles caused it to take longer for the tightlacer to wear a corset laced closed at the back. Thereafter, reducing another couple of inches would not be much more difficult, but each inch after a six-inch reduction may take a year to achieve.

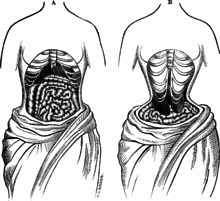

The diminished waist and tight corset reduce the volume of the torso. This is sometimes reduced even further by styles of corset that force the torso to taper toward the waist, which pushes the lower ribs inward. As a consequence, internal organs are moved closer together and out of their original positions.

Tightlacing was believed to have been a contributing factor in the death of female impersonator Joseph Hennella in 1912.[4]

Notable adherents

- Empress Elisabeth of Austria (Sisi); 19.5 inches (49-50 cm)

- Polaire; about 1914; 13–14 inches (33–36 cm)

- Cathie Jung; 2006; 15 inches (38 cm)

- Dita Von Teese; 16.5 inches (42 cm)

See also

Tightlacing-related

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tightlacing. |

- Varrin, Claudia (2003). Erotic Surrender: The Sensual Joys of Female Submission. Citadel Press. pp. 187–188. ISBN 0-8065-2400-6.

- "Corset Seasoning Mini-Series – Lucy's Corsetry". lucycorsetry.com.

- Vogue cover model shocks with 33cm waist MADONNA magazine from August 31st, 2011

- "Tight lacing is believed to have killed an actor". St Louis Post-Dispatch. 4 November 1912. p. 1.

Further reading

- Le corset; étude physiologique et pratique

- Tight Lacing, Peter Farrer. ISBN 0-9512385-8-2

- The Corset and the Crinoline. A Book of Modes and Costumes from remote periods to the present time. Lord William Barry. (1869)

- Valerie Steele, The Corset: A Cultural History. Yale University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-300-09953-3.

- David Kunzle, "Fashion and fetishism: a social history of the corset, tight-lacing, and other forms of body-sculpture in the West", Rowman and Littlefield, 1982, ISBN 0-8476-6276-4

- Bound To Please: A History of the Victorian Corset, Leigh Summers, Berg Publishers, 2001. ISBN 1-85973-510-X