Tide dial

A tide dial, also known as a Mass[2] or scratch dial,[3][4] is a sundial marked with the canonical hours rather than or in addition to the standard hours of daylight. Such sundials were particularly common between the 7th and 14th centuries in Europe, at which point they began to be replaced by mechanical clocks. There are more than 3,000 surviving tide dials in England and at least 1,500 in France.

Name

The name tide dial preserves the Old English term tīd, used for hours and canonical hours prior to the Norman Conquest of England, after which the Norman French hour gradually replaced it. The actual Old English name for sundials was dægmæl or "day-marker".

History

Jews long recited prayers at fixed times of day. Psalm 119 in particular mentions praising God seven times a day,[5][6] and the apostles Peter and John are mentioned attending afternoon prayers.[7] Christian communities initially followed numerous local traditions with regard to prayer, but Charlemagne compelled his subjects to follow the Roman liturgy and his son Louis the Pious imposed the Rule of St Benedict upon their religious communities.

The canonical hours adopted by Benedict and imposed by the Frankish kings were the office of matins in the wee hours of the night,[lower-alpha 1] Lauds at dawn, Prime at the 1st hour of sunlight, Terce at the 3rd, Sext at the 6th, Nones at the 9th,[6] Vespers at sunset,[10] and Compline before retiring in complete silence.[11] Monks were called to these hours by their abbot[12] or by the ringing of the church bell, with the time between services organized in reading the Bible or other religious texts, in manual labor, or in sleep.

The need for these monastic communities and others to organize their times of prayer prompted the establishment of tide dials built into the walls of churches. They began to be used in England in the late 7th century and spread from there across continental Europe through copies of Bede's works and by the Saxon and Hiberno-Scottish missions. Within England, tide dials fell out of favor after the Norman Conquest.[13] By the 13th century, some tide dials—like that at Strasbourg Cathedral—were constructed as independent statues rather than built into the walls of the churches. From the 14th century onwards, the cathedrals and other large churches began to use mechanical clocks and the canonical sundials lost their utility, except in small rural churches, where they remained in use until the 16th century.

There are more than 3,000 surviving tide dials in England[14][lower-alpha 2] and at least 1,500 in France,[16] mainly in Normandy, Touraine, Charente, and at monasteries along the pilgrimage routes to Santiago de Compostella in northwestern Spain.

Design

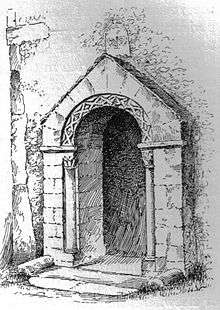

With Christendom confined to the Northern Hemisphere, the tide dials were often carved vertically onto the south side of the church chancel at eye level near the priest's door. In an abbey or large monastery, dials were carefully carved into the stone walls, while in rural churches they were very often just scratched onto the wall.

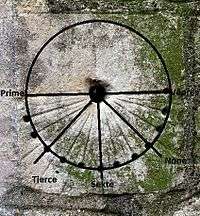

Some tide dials have a stone gnomon, but many have a circular hole which is used to hold a more easily replaced or adjusted wooden gnomon. These gnomons were perpendicular to the wall and cast a shadow upon the dial, a semicircle divided into a number of equal sectors. Most dials have supplementary lines marking the other 8 daytime hours, but are characterized by their noting the canonical hours particularly. The lines for the canonical hours may be longer or marked with a dot or cross. The divisions are seldom numbered.

Dials often have holes along the circumference of their semicircle. As additional gnomons were needless and these holes are often quite shallow, Cole suggests they were used to quickly and easily reconstruct the tide dials following a fresh whitewash of the church walls with chalk or lime.[17]

Examples

Bewcastle Cross

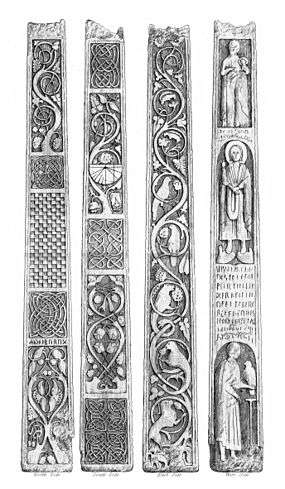

The oldest surviving English tide dial is on the 7th- or 8th-century Bewcastle Cross in the church graveyard of St Cuthbert's in Bewcastle, Cumbria. It is carved on the south face of a Celtic cross at some height from the ground and is divided by five principal lines into four tides. Two of these lines, those for 9 am and noon, are crossed at the point. The four spaces are further subdivided so as to give the twelve daylight hours of the Romans. On one side of the dial, there is a vertical line which touches the semicircular border at the second afternoon hour. This may be an accident, but the same kind of line is found on the dial in the crypt of Bamburgh Church, where it marks a later hour of the day. The sundial may have been used for calculating the date of the spring equinox and hence Easter.[18][19]

Bewcastle Cross

Bewcastle Cross Its four faces, with the tide dial on the second from the left

Its four faces, with the tide dial on the second from the left

Nendrum Sundial

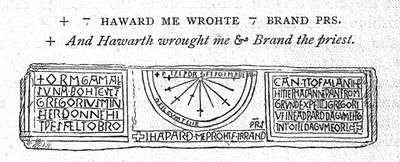

Nendrum Monastery in Northern Ireland, supposedly founded in the 5th century by St Machaoi, now has a reconstructed tide dial.[20] The 9th-century tide dial gives the name of its sculptor and a priest.

The pillar bearing the tide dial

The pillar bearing the tide dial- The Nendrum sundial

Kirkdale Sundial

The 1056 x 1065 tide dial at St Gregory's Minster in Kirkdale, North Yorkshire, has four principal divisions marked by five crossed lines, subdivided by single lines. One marking ¼ of the way between sunrise and noon is an incised cross that would indicate about 9 am at midwinter and 6 am at midsummer. It was dedicated to a "Hawarth".[21]

St Gregory's Minster

St Gregory's Minster Its tide dial

Its tide dial Another image of the dial[22]

Another image of the dial[22]

Gallery

Proper tide dials prominently displaying the canonical hours:

- A photograph of St Andrew's tide dial in Bishopstone, East Sussex, England

Tide dial at St Peter's in Bywell, Northumberland, England

Tide dial at St Peter's in Bywell, Northumberland, England Tide dial at St Andrew's at Hempstead near Lessingham, Norfolk, England

Tide dial at St Andrew's at Hempstead near Lessingham, Norfolk, England- Tide dial of Notre Dame in Uzeste, France

- Tide dial of the church in Dahmen, Germany

- Tide dial of St Peter's in St-Pierre-du-Palais, France

The tide dial at St Marien's in Homberg, Germany

The tide dial at St Marien's in Homberg, Germany The tide dial at St Beuno's in Clynnog Fawr, Wales (10–11th c.)

The tide dial at St Beuno's in Clynnog Fawr, Wales (10–11th c.)

A tide dial on the church at Berka, Germany (15th c.)

A tide dial on the church at Berka, Germany (15th c.)

Other ecclesiastical sundials ("Mass dials") used to determine times for prayer and Mass during the same period:

- Two sundials on a buttress at St Mary's in Chalgrove, Oxfordshire, England

Sundial with half-hour marks at St Martin's in Cheselbourne, Dorset, England

Sundial with half-hour marks at St Martin's in Cheselbourne, Dorset, England

Sundial preserved amid a newer wall at SS Peter & Paul's in West Clandon, Surrey, England

Sundial preserved amid a newer wall at SS Peter & Paul's in West Clandon, Surrey, England

- The sundial at SS Peter & Martin's in Condé-on-the-Ifs, France

_Bonaval_2_0_2_Fachada_Sur_Reloj_sol.png) The sundial on the monastery church at Bonaval, Spain

The sundial on the monastery church at Bonaval, Spain A sundial at St Marien's in Stelzen, Germany, marked with Runic numerals

A sundial at St Marien's in Stelzen, Germany, marked with Runic numerals A sundial at the Istanbul Museum marked with Greek numerals

A sundial at the Istanbul Museum marked with Greek numerals- The sundial at Zvartnots Cathedral, marked with Armenian numerals

- The sundial on the church patio at San Jerónimo Tlacochahuaya, Mexico (16th c.)

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mass dials. |

Notes

- It began at about the 8th hour of night (⅔ of the way between sunset and sunrise) which in the longer nights between November 1 and Easter allowed time for study before beginning the dawn office of lauds, but in the shorter summer months required curtailment of the vigil service so that lauds could then begin after only a brief interval to permit the monks to visit the toilet.[8] Sunday services being longer, they necessarily began somewhat earlier.[9]

- Cole gives a list of 1300 English churches with tide dials.[15]

References

Citations

- Wall (1912), pp. 67 & 97.

- Cook (2012).

- Horne (1929).

- Cole (1935).

- Ps. 119:164.

- Rule of Benedict, Ch. 16.

- Acts 3:1.

- Rule of Benedict, Ch. 8.

- Rule of Benedict, Ch. 11.

- Rule of Benedict, Ch. 41.

- Rule of Benedict, Ch. 42 .

- Rule of Benedict, Ch. 47.

- "Tide, Mass or Scratch Dials", Pastfinders.

- "Mass Dials", Official site, British Sundial Society.

- Cole (1935), pp. 10-16.

- Schneider, Denis (2014), "Les Cadrans Canoniaux", L'Astronomie, No. 76, pp. 58–61.

- Cole (1935), pp. 2-3.

- Bewcastle: A Brief Historical Sketch.

- "Bilberries and Tickled Trout: Reflections on the Bewcastle Cross".

- "Nendrum Monastic Site", Department of the Environment, archived from the original on 2009-04-16.

- Wall (1912), p. 66.

- Wall (1912), p. 66.

- Dackett, Eliza; Julia Skinner (2006), Ancient Britain: Land of Mystery and Legend, Francis Frith, p. 93, ISBN 1-84589-276-3.

- The Italian Riviera, Milan: Touring Club of Italy, 2001, p. 52.

Bibliography

- Cole, T.W. (1935), Origin and Use of Church Scratch-Dials (PDF), London: Ed. Murray & Co., ISBN 978-0953897711.

- Cole, T.W. (1938), Medieval Church Sundials (PDF), Suffolk Institute of Archaeology & History, Vol. 23, Pt. 2, pp. 148–154.

- Cook, Alan (2012), Time Addendum to Mass Dials on Yorkshire Churches, BSS Monographs, British Sundial Society, ISBN 978-0955887253.

- Green, Arthur Robert (1926), Incised Dials or Mass-Clocks, London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- Horne, Abbot Ethelbert (1929), Scratch Dials: Their Description and History, London: Simpkin Marshall.

- Tupper, Frederick Jr. (1895), Anglo-Saxon Dæg-Mæl, Baltimore: Modern Language Association of America.

- Wall, J. Charles (1912), Porches & Fonts, London: Wells, Gardner, Darton & Co.

- Whitley, H. Michell (1919), Primitive Sundials on West Sussex Churches (PDF), Sussex Archeological Collections, Vol. 60, pp. 126–140.

External links

- Exhaustive treatment of Mass dials in the Gironde, France, at Wikicommons

- Tide dials in Touraine, France

- Tide dials in Tarn, France

- Tide dials decoded by P.T.J. Rumley

- Tide dials in Sussex, Britain

- The Kirkdale Sundial: 1 & 2

- The Bishopstone Sundial: 1 & 2