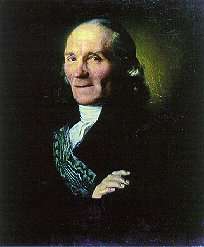

Carl Peter Thunberg

Carl Peter Thunberg, also known as Karl Peter von Thunberg, Carl Pehr Thunberg, or Carl Per Thunberg (11 November 1743 – 8 August 1828), was a Swedish naturalist and an apostle of Carl Linnaeus. He has been called "the father of South African botany", "pioneer of Occidental Medicine in Japan" and the "Japanese Linnaeus".

Carl Peter Thunberg | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 11 November 1743 Jönköping, Sweden |

| Died | 8 August 1828 (aged 84) Thunaberg, Uppland, Sweden |

| Nationality | Swedish |

| Other names |

|

| Occupation | Naturalist |

Early life

Thunberg was born and grew up in Jönköping, Sweden. At the age of 18, he entered the Swedish Uppsala University where he was taught by the famous Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus who was mainly known for his work Philosophia Botanica (1751). Thunberg graduated in 1767 after only 6 years of studying. To deepen his knowledge in botany, medicine and natural history, he was encouraged by Linnaeus in 1770 to travel to Paris and Amsterdam. In Amsterdam and Leiden where he stayed to study the city's collection of plants and musea, Thunberg met the Dutch botanist and physician, Johannes Burman and his son Nicolaas Burman who himself had been a disciple of Linnaeus.[1]

Having heard of Thunberg's inquisitive mind, his skills in botany and medicine and Linnaeus' high esteem of his Swedish pupil, Johannes Burman and Laurens Theodorus Gronovius, a councillor of Leiden, convinced Thunberg to travel to either the West or the East Indies to collect plants and animal specimen for the botanic garden at Leiden which was still lacking exotic exhibits. Thunberg who had ever since been fascinated by the secretive and mainly unknown East Indies was eager to travel to the Cape of Good Hope and apply his knowledge.[2]

With the help of Burman and Gronovius, Thunberg entered the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, V.O.C.) as a surgeon on board of the Schoonzicht.[3] As the East Indies were under Dutch control, the only way to enter the colonies was via the V.O.C. Hence, Thunberg debarked in December 1771.[4] In March 1772, he reached Cape Town in South Africa.

Thunberg in South Africa

During his three-year stay, the Swede managed to perfect his Dutch and delve deeper into the scientific knowledge, culture and societal structure of the "Hottentotten", the Dutch name for the Khoikhoi, the native people of Western South Africa. Thunberg's travel to Africa is described in the second volume of his travelogue.

The Khoikhoi were the first foreign culture with which the Swede was confronted.[5] The different customs and traditions of the native people elicited both his disgust and admiration. For example, he considered the Khoikhoi's custom to grease their skin with fat and dust as an obnoxious habit about which he wrote in his travelogue:

"For uncleanliness, the Hottentots have the greatest love. They grease their entire body with greasy substances and above this, they put cow dung, fat or something similar."[6]

Yet, this harsh judgement is moderated by the reason he saw for this practice and so he continues that:

"This stops up their pores and their skin is covered with a thick layer which protects it from heat in Summer and from cold during Winter.".[6]

This attitude – to try to justify rituals he did not understand – also marks his encounter with the Japanese people.

Since the main purpose for his journey was to collect specimen for the gardens in Leiden, Thunberg regularly undertook field trips and journeys into the interior of South Africa. Between September 1772 and January 1773, he accompanied the Dutch superintendent of the V.O.C garden, Johan Andreas Auge. Their journey took them to the north of Saldanha Bay, east along the Breede Valley through the Langkloof as far as the Gamtoos River and returning by way of the Little Karoo.[7] During this expedition and also later on, Thunberg kept regular contact with scholars in Europe, especially the Netherlands and Sweden, but also with other members of the V.O.C who sent him animal skins. Shortly after returning, Thunberg met Francis Masson, a Scots gardener who had come to Cape Town to collect plants for the Royal Gardens at Kew. They were immediately drawn together by their shared interests. During one of their trips, they were joined by Robert Jacob Gordon, on leave from his regiment in the Netherlands. Together, the scientists undertook two further inland expeditions.

During his three expeditions into the interior, Thunberg collected a significant number of specimens of both flora and fauna. At the initiative of Linnaeus, he graduated at Uppsala as Doctor of Medicine in absentia, while he was at the Cape in 1772. Thunberg left the Cape for Batavia on 2 March 1775. He arrived in Batavia on 18 May 1775, and left for Japan on 20 June.

Stay in Japan

In August 1775, he arrived at the Dutch factory of the V.O.C. (Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie) at Dejima, a small artificial island (120 m by 75 m) in the Bay of Nagasaki connected to the city by a single small bridge. However, just like the Dutch merchants, Thunberg was hardly allowed to leave the island. These severe restrictions to the freedom to move had been imposed by the Japanese shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu in 1639 after the Portuguese who had been the first to arrive in Japan in 1543, had garnered the shogun's rage through their missionary attempts. The only locals who were allowed regular contact with the Dutch were the interpreters of Nagasaki and the relevant authorities of the city.[8]

Shortly after the Schoonzicht's arrival on Deshima, Thunberg was appointed head surgeon of the trading post. To still be able to collect specimen of Japanese plants and animals as well as to gather information on the population, Thunberg soon began to systematically construct networks with the interpreters by sending them small notes containing medical knowledge and receiving botanical knowledge or rare Japanese coins in return. Quickly, the news spread that a well-educated Dutch physician was in town who seemed to be able to help the local doctors cure the Dutch disease, another word for syphilis. As a result, the appropriate authorities granted him more and more visits to the city and finally even allowed him one-day trips into the vicinity of Nagasaki where Thunberg had the chance to collect specimen by himself.[9]

During his visits in town, Thunberg began to recruit disciples, mainly the Nagasaki interpreters and local physicians. His major knowledge contribution was in the teachings of new medical treatments such as a mercury cure for the "Dutch Disease" and of the production of new medicine. During this process, however, he also instructed his pupils in the Dutch language and European manners of conduct, thus furthering the growing interest into the Dutch and European culture on the side of the Japanese, known under the term rangaku.[10] The Swedish writer Marie-Christine Skuncke[11] even points out that Thunberg who had brought some seeds of European vegetables with him, showed the Japanese some botanical practices, thus contributing significantly to an expansion of the Japanese horticulture.

On the other hand, Thunberg also profited from his teachings himself. As a former medical student he was mainly interested in medical knowledge, and the Japanese showed him the practice of acupuncture. The co-operation of Thunberg and the local physicians even led to a knowledge fusion which brought about a new acupuncture point called shakutaku. The discovery of shakutaku was a result of Thunberg's anatomic knowledge and the Japanese' traditional medicine of neuronic moxibustion. Yet, he likewise brought back knowledge on Japan's religion and societal structure, thus boosting an increasing interest into Japan, an early cultural form of Japonism.[12][13]

In both countries, Thunberg's knowledge exchange hence led to a cultural opening-up effect which too manifested itself also in the spread of universities and boarding schools which taught knowledge on the other culture. For this reason, Thunberg has been given the title of being "the most important eye witness of Tokugawa Japan in the eighteenth century".[14]

Due to his scientific reputation, Thunberg was given the opportunity in 1776 to accompany the Dutch ambassador M. Feith to the shogun's court in Edo, today's Tokyo. During that journey, the Swede was given the chance to collect a great number of specimen of plants and animals and likewise to talk to Japanese locals in the villages they traversed on their way. It is in this time that Thunberg wrote two of his scientific masterpieces, the Flora Japonica (1784) and the Fauna Japonica (1833). The latter was completed by the German traveller Philipp Franz von Siebold who visited Japan between 1823 and 1829. Yet, von Siebold based the Fauna Japonica on Thunberg's notes which he carried with him all the time in Japan.[15]

Additionally, on his way to Edo, Thunberg managed to obtain a vast number of Japanese coins which he described in detail in the fourth volume of his travelogue, Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the Years 1770 and 1779. The coins presented an important informational repository on the culture, religion and history of Japan, as their possession as well as their export by foreigners had been strictly forbidden by the shogun. This prohibition had been imposed to prevent the Empire of China and other rivals of the shogunate from copying the money and flooding the Japanese markets with forged coins.[16] Consequently, Thunberg's transport of Japanese coins granted European scholars an entirely new perspective on Japan's monetary economy and allowed them to draw conclusions on Japan's culture and religion through decorations on the coins and the materials used to produce the currency.

In November 1776, after Thunberg had returned from his trip to the shogun's court, he left Japan and went on to Java, an island that nowadays belongs to Indonesia. From there on, he travelled to Ceylon in July 1777, today's Sri Lanka. Here again, his major interest lay in collecting plants and other specimen.

In 1778, Thunberg left Ceylon to return to Europe.

Return to Sweden

In February 1778, Thunberg left Ceylon for Amsterdam, passing by at the Cape and staying there for two weeks. He finally arrived at Amsterdam in October 1778. In 1776, Thunberg had been elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

He returned to Sweden in 1779. But first he made a short trip to London and made the acquaintance of Sir Joseph Banks. He saw there the Japanese collection from the 1680s of the German naturalist Engelbert Kaempfer (1651–1716), who had preceded him at Dejima. He also met Forster, who introduced him to his collections he had obtained during Cook's second voyage.

On arrival in Sweden in March 1779, he was informed of the death of Linnaeus, one year earlier. He was first appointed botanical demonstrator in 1777, and in 1781 professor of medicine and natural philosophy at the University of Uppsala. His publications and specimens resulted in many new taxa.

He published his Flora japonica in 1784, and in 1788 he began to publish his travels. He completed his Prodromus plantarum in 1800, his Icones plantarum japonicarum in 1805, and his Flora capensis in 1813. He published numerous memoirs in the transactions of many Swedish and other scientific societies, of sixty-six of which he was an honorary member.

In 1809 he became correspondent, and in 1823 associated member of the Royal Institute of the Netherlands.[17]

He died at Thunaberg near Uppsala on 8 August 1828.

Reasons for his travels

Although travels through Europe and to newly discovered countries were not uncommon during the Age of Enlightenment, the question why Thunberg chose the East Indies and particularly Japan as his destination remains. Moreover, even though the Enlightenment's "market of ideas" was rich of travelogues about Linnaeus unknown lands and cultures, Thunberg's account on Japan took an extraordinary position and was even translated into German, English and French.[18] Hence, many scholars have tried to determine the reasons for Thunberg's travel at that particular time and the outstanding success of his travelogue. Out of the relevant literature, three main explanations can be filtered out.

- Next to being encouraged by Linnaeus and Gronovius to travel to Japan, the fact that for half a century, no new information on the mysterious country in the East had reached Europe attracted Thunberg to provide new insights on the Japanese. In 1690, Engelbert Kaempfer, a German traveller, had sailed to Japan and spent two years on the island of Deshima. Kaempfer's travelogue which was published in 1729 became a famous work on the shogunate; yet, when Thunberg came to Japan, Kaempfer's writings were already more than fifty years old.[19][20] The time was right for new knowledge.

- The Age of Enlightenment furthered this scientific hunger for new information. In the light of the increasing emphasis on using the rational human mind, many students were keen to leave the boundaries of Europe and apply their knowledge and gather new insights through empirical travels into the unknown.[20]

- Thunberg himself was a very inquisitive and intelligent man, a "person of acute mind" (Screech, 2012, p. 2) who always sought new challenges. Hence, undertaking the journey was in Thunberg's personal interest and complied well with his character.

Thunbergia, thunbergii

A genus of tropical plants (Thunbergia, family Acanthaceae), which are cultivated as evergreen climbers, is named after him.

Thunberg is cited in naming some 254 species of both plants and animals (though significantly more plants than animals). Notable examples of plants referencing Thunberg in their specific epithets include:-

Gallery

Flora Japonica

Flora Japonica Prodromus Plantarum Capensium

Prodromus Plantarum Capensium Botanical plate from Carl Peter Thunberg: Iris. Dissertation printed in Uppsala 1782.

Botanical plate from Carl Peter Thunberg: Iris. Dissertation printed in Uppsala 1782. Title page of first volume of Carl Peter Thunberg: Resa [Travel]. First edition, in Swedish, printed 1788.

Title page of first volume of Carl Peter Thunberg: Resa [Travel]. First edition, in Swedish, printed 1788.

Selected publications

- Botany

- Flora Japonica (1784)

- Edo travel accompaniment.

- Prodromus Plantarum Capensium (Uppsala, vol. 1: 1794, vol. 2: 1800)[22]

- Flora Capensis (1807, 1811, 1813, 1818, 1820, 1823)

- Voyages de C.P. Thunberg au Japon par le Cap de Bonne-Espérance, les Isles de la Sonde, etc.

- Icones plantarum japonicarum (1805)

- Entomology

- Donationis Thunbergianae 1785 continuatio I. Museum naturalium Academiae Upsaliensis, pars III, 33–42 pp. (1787).

- Dissertatio Entomologica Novas Insectorum species sistens, cujus partem quintam. Publico examini subjicit Johannes Olai Noraeus, Uplandus. Upsaliae, pp. 85–106, pl. 5. (1789).

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, 1743–1828, praeses. [1784-1795] D.D. Dissertatio entomologia sistens insecta svecica Åkerman, Jacob, 1770–1829, respondent; Becklin, Petrus Ericus, respondent, Borgström, Johannes, respondent; Haij, Isaacus, respondent; Kinmanson, Samuel, 1771–1830, respondent; Kullberg, Jonas, respondent; Sebaldt, Carl Fredrik, respondent; Wenner, Gustavus Magnus, respondent; Westman, Sten Edvard, 1777–1836, respondent Upsaliae :apud Johan. Edman,[1784-1795]

- D. D. Dissertatio entomologica sistens Insecta Suecica. Exam. Jonas Kullberg. Upsaliae, pp. 99–104 (1794).

See also

- An'ei – Japanese era names

- Kuze Hirotami

- Sakoku

- List of Westerners who visited Japan before 1868

Notes

- Svedelius, N. (1944). Carl Peter Thunberg (1743–1828) on His Bicentenary. Isis, 35 (2), p. 129

- Thunberg, C. P. (1791). Resa uti Europa, Africa, Asia, förrättad åren 1770–1779. Tredje Band. Published by J. Edman, Uppsala, Sweden, p. 22

- "Carel Pieter Thunbergh". Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) Archiefinventarissen. : Nationaal Archief (Netherlands). Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- Skuncke 2013, pp. 39, 99

- Jung 2002, p. 95

- Thunberg 1986, p. 180

- Thunberg, C. P. (1793). Travels at the Cape of Good Hope, 1772–1775. Emeritus Prof. V. S. Forbes, London, p. 27

- Totman, C. D. (2000). A History of Japan. Blackwell Publishers Ltd, Oxford and Malden, p. 275

- Thunberg, C. P. (1796). Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the Years 1770 and 1779. Published by W. Richardson, London, UK, p. 37

- Screech, T. (2012). Japan Extolled and Decried: Carl Peter Thunberg and the Shogun’s Realm, 1775 – 1776. Routledge: Taylor and Francis Group, London and New York, p. 59

- Skuncke 2013, p. 101

- Skuncke 2013, p. 125

- Fujita, R. (1944). Researches on Pressation-Points and Papule-Points and Related Subjects. Ninth Report: From the Angle of Oriental Medicine, Part 2. Kanazawa, Japan, p. 59

- Ortolani, B. (1995). The Japanese Theatre: From Shamanistic Ritual to Contemporary Pluralism. Princeton UP, p. 281

- Nordenstamm, B. (2013). Carl Peter Thunberg and Japanese Natural History. Asian Journal of Natural and Applied Sciences, 2 (2), pp. 1 – 7

- Kornicki, P. (2010). Catalogue of the Japanese Coin Collection (Pre-Meiji) at the British Museum. British Museum Research Publication n°174, pp. 28–30

- "Carl Peter Thunberg (1743–1828)". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- Skuncke, 2013, p. 261

- Rietbergen, P. (2004.) Becoming Famous in the Eighteenth Century: Carl Peter Thunberg Between Sweden, the Netherlands and Japan. De Achttiende Eeuw, 36 (1), pp. 50–61, p. 65

- Jung 2002, pp. 90–92

- IPNI. Thunb.

- Prodromus Plantarum Capensium at Biodiversity Heritage Library. (see External links below).

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Jung, C. (2002). Kaross und Kimono: „Hottentotten“ und Japaner im Spiegel des Reiseberichts von Carl Peter Thunberg, 1743 – 1828. [Kaross and Kimono: “Hottentots” and Japanese in the Mirror of Carl Peter Thunberg's Travelogue, 1743 – 1828]. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart, Germany

- Skuncke, Marie-Christine (2013). Carl Peter Thunberg: Botanist and Physician.Swedish Collegium for Advanced Studies, Uppsala, Sweden

- Skuncke, Marie-Christine. Carl Peter Thunberg, Botanist and Physician, Swedish Collegium for Advanced Study 2014

- Thunberg, C. P. (1986). Travels at the Cape of Good Hope, 1772–1775 : based on the English edition London, 1793–1795. (Ed. V. S. Forbes) London

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carl Peter Thunberg. |