Three-domain system

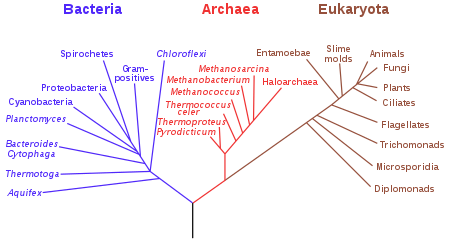

The three-domain system is a biological classification introduced by Carl Woese et al. in 1990[1][2] that divides cellular life forms into archaea, bacteria, and eukaryote domains. The key difference from earlier classifications is the splitting of archaea from bacteria.

Background

Woese argued, on the basis of differences in 16S rRNA genes, that bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes each arose separately from an ancestor with poorly developed genetic machinery, often called a progenote. To reflect these primary lines of descent, he treated each as a domain, divided into several different kingdoms. Originally his split of the prokaryotes was into Eubacteria (now Bacteria) and Archaebacteria (now Archaea). Woese initially used the term "kingdom" to refer to the three primary phylogenic groupings, and this nomenclature was widely used until the term "domain" was adopted in 1990.[2]

Acceptance of the validity of Woese's phylogenetically valid classification was a slow process. Prominent biologists including Salvador Luria and Ernst Mayr objected to his division of the prokaryotes.[3][4] Not all criticism of him was restricted to the scientific level. A decade of labor-intensive oligonucleotide cataloging left him with a reputation as "a crank," and Woese would go on to be dubbed as "Microbiology's Scarred Revolutionary" by a news article printed in the journal Science.[5] The growing amount of supporting data led the scientific community to accept the Archaea by the mid-1980s.[6] Today, few scientists cling to the idea of a unified Prokarya.[7]

Classification

_crop.jpg)

The three-domain system adds a level of classification (the domains) "above" the kingdoms present in the previously used five- or six-kingdom systems. This classification system recognizes the fundamental divide between the two prokaryotic groups, insofar as Archaea appear to be more closely related to Eukaryotes than they are to other prokaryotes – bacteria-like organisms with no cell nucleus. The current system sorts the previously known kingdoms into these three domains: Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya.

Domain Archaea

The Archaea are prokaryotic, with no nuclear membrane, distinct biochemistry, and RNA markers from bacteria. The Archaeans possess unique, ancient evolutionary history for which they are considered some of the oldest species of organisms on Earth, most notably their diverse, exotic metabolisms, which allow them to feed on inorganic matter. Originally classified as exotic bacteria, and then reclassified as archaebacteria, the only easy way to distinguish them on sight from "true" bacteria is by the extreme, harsh environments in which they notoriously thrive.

Some examples of archaeal organisms are:

- methanogens – which produce the gas methane

- halophiles – which live in very salty water

- thermoacidophiles – which thrive in acidic high-temperature water

Domain Bacteria

The Bacteria are also prokaryotic; their domain consists of cells with bacterial rRNA, no nuclear membrane, and whose membranes possess primarily diacyl glycerol diester lipids. Traditionally classified as bacteria, many thrive in the same environments favored by humans, and were the first prokaryotes discovered; they were briefly called the Eubacteria or "true" bacteria when the Archaea were first recognized as a distinct clade.

Most known pathogenic prokaryotic organisms belong to bacteria (see[8] for exceptions). For that reason, and because the Archaea are typically difficult to grow in laboratories, Bacteria are currently studied more extensively than Archaea.

Some examples of bacteria include:

- Cyanobacteria – photosynthesizing bacteria that are related to the chloroplasts of eukaryotic plants and algae

- Spirochaetes – Gram-negative bacteria that include those causing syphilis and Lyme disease

- Actinobacteria – Gram-positive bacteria including Bifidobacterium animalis which is present in the human large intestine

Domain Eukarya

Eukarya are uniquely organisms whose cells contain a membrane-bound nucleus (eukaryotes, eukaryotic). They include many large single-celled organisms and all known non-microscopic organisms. A partial list of eukaryotic organisms includes:

- Kingdom Fungi or fungi

- Saccharomycotina – includes true yeasts

- Basidiomycota – includes mushrooms

- Kingdom Plantae or plants

- Bryophyta – mosses

- Magnoliophyta – flowering plants

- Kingdom Animalia or animals

- Chordata – includes vertebrates as a subphylum

Niches

Each of the three cell types tends to fit into recurring specialities or roles. Bacteria tend to be the most prolific reproducers, at least in moderate environments. Archaeans tend to adapt quickly to extreme environments, such as high temperatures, high acids, high sulfur, etc. This includes adapting to use a wide variety of food sources. Eukaryotes are the most flexible with regard to forming cooperative colonies, such as in multi-cellular organisms, including humans. In fact, the structure of a Eukaryote is likely to have derived from a joining of different cell types, forming organelles.

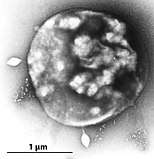

Parakaryon myojinensis (incertae sedis) is a single-celled organism known by a unique example. "This organism appears to be a life form distinct from prokaryotes and eukaryotes",[9] with features of both.

Alternatives

Parts of the three-domain theory have been challenged by scientists including Ernst Mayr, Thomas Cavalier-Smith, and Radhey S. Gupta.[10][11][12] In particular, Gupta argues that the primary division within prokaryotes should be among those surrounded by a single membrane (monoderm), including gram-positive bacteria and archaebacteria, and those with an inner and outer cell membrane (diderm), including gram-negative bacteria. He claims that sequences of features and phylogenies from some highly conserved proteins are inconsistent with the three-domain theory, and that it should be abandoned despite its widespread acceptance.

Recent work has proposed that Eukarya may have actually branched off from the domain Archaea. According to Spang et al. Lokiarchaeota forms a monophyletic group with eukaryotes in phylogenomic analyses. The associated genomes also encode an expanded repertoire of eukaryotic signature proteins that are suggestive of sophisticated membrane remodelling capabilities.[13] This work suggests a two-domain system as opposed to the near universally adopted three-domain system.

See also

- Archaea

- Bacterial phyla

- Eocyte hypothesis

- Monera

- Phylogenetic tree

- Taxonomy

- Two-empire system

- Protista - the kingdom which is unclassified in three-domain system

References

- Woese CR, Fox GE (November 1977). "Phylogenetic structure of the prokaryotic domain: the primary kingdoms". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 74 (11): 5088–90. Bibcode:1977PNAS...74.5088W. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.11.5088. PMC 432104. PMID 270744.

- Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML (June 1990). "Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (12): 4576–9. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.4576W. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. PMC 54159. PMID 2112744.

- Mayr, Ernst (1998). "Two empires or three?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 95 (17): 9720–9723. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.9720M. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.17.9720. PMC 33883. PMID 9707542.

- Sapp, Jan A. (December 2007). "The structure of microbial evolutionary theory". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. 38 (4): 780–95. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2007.09.011. PMID 18053933.

- Morell, V. (1997-05-02). "Microbiology's scarred revolutionary". Science. 276 (5313): 699–702. doi:10.1126/science.276.5313.699. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 9157549.

- Sapp, Jan A. (2009). The new foundations of evolution: on the tree of life. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-73438-2.

- Koonin, Eugene (2014). "Carl Woese's vision of cellular evolution and the domains of life". RNA Biology. RNA Biol. 11 (3): 197–204. doi:10.4161/rna.27673. PMC 4008548. PMID 24572480.

- Eckburg, Paul B.; Lepp, Paul W.; Relman, David A. (2003). "Archaea and their potential role in human disease". Infection and Immunity. 71 (2): 591–596. doi:10.1128/IAI.71.2.591-596.2003. PMC 145348. PMID 12540534.

- Yamaguchi M, Mori Y, Kozuka Y, Okada H, Uematsu K, Tame A, Furukawa H, Maruyama T, Worman CO, Yokoyama K (2012). "Prokaryote or eukaryote? A unique microorganism from the deep sea". Journal of Electron Microscopy. 61 (6): 423–31. doi:10.1093/jmicro/dfs062. PMID 23024290.

- Gupta, Radhey S. (1998). "Life's Third Domain (Archaea): An Established Fact or an Endangered Paradigm?: A New Proposal for Classification of Organisms Based on Protein Sequences and Cell Structure". Theoretical Population Biology. 54 (2): 91–104. doi:10.1006/tpbi.1998.1376. PMID 9733652.

- Mayr, E. (1998). "Two empires or three?". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95 (17): 9720–9723. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.9720M. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.17.9720. PMC 33883. PMID 9707542.

- Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (2002). "The neomuran origin of archaebacteria, the negibacterial root of the universal tree and bacterial megaclassification". Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 52 (1): 7–76. doi:10.1099/00207713-52-1-7. PMID 11837318.

- Spang, Anja (2015). "Complex archaea that bridge the gap between prokaryotes and eukaryotes". Nature. 521 (7551): 173–179. Bibcode:2015Natur.521..173S. doi:10.1038/nature14447. PMC 4444528. PMID 25945739.