Thomas Muffet

Thomas Muffet (also Moufet, Mouffet,[1] or Moffet) (1553 – 5 June 1604) was an English naturalist and physician. He is best known for his Puritan beliefs, his study of insects in regard to medicine (particularly spiders), his support of the Paracelsian system of medicine, and his emphasis on the importance of experience over reputation in the field of medicine.

Thomas Muffet | |

|---|---|

Unpublished title page engraving by William Rogers with a portrait of Muffet at the bottom | |

| Born | 1553 Shoreditch, London, England |

| Died | 5 June 1604 Bulbridge Farm, Wilton, Wiltshire |

| Nationality | English |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Known for | Insects in medicine |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Natural philosophy, medicine |

| Influences | Paracelsus, T. Zwinger |

Biography

Early life and education

Thomas Muffet was born in 1553 as the second son to haberdasher Thomas Moffet[2], in Shoreditch, London. From the ages 8 to 16, Muffet attended the Merchant Taylors' School. In May 1569, he matriculated at Trinity College, Cambridge but transferred to Gonville Hall in October 1572. He graduated in 1573, when he received his bachelor's degree.[3] Afterward, Muffet studied medicine with Thomas Lorkin and John Caius. Three years later, he began his master's degree at Trinity and was expelled from Gonville. In Spring 1578 Muffet boarded with Felix Platter, chief physician of Basel, where he adopted the Paracelsian system of medicine.[4] In 1579, Muffet was awarded a doctorate in medicine from Basel University. His thesis was entitled De amodinis medicamentis (1578).

Later life and post-graduate work

The year after receiving his MD, in 1580, Thomas Muffet studied silkworm anatomy in Italy before finally returning to England. That December, Muffet married his first wife, Jane, in St Mary Colechurch, London. Two years later, he was recognized as a qualified physician by the College of Physicians in London. This was not expected, as Muffet was a strong advocate for the Paracelsian system of medicine, which was not widely respected by the medical community. The same year, Muffet was sent by Sir Francis Walsingham on a diplomatic mission to Denmark to present the order of the garter to King Frederick. It was here he met both Tycho Brahe and Petrus Severinus, though there is no evidence as to either's intellectual influence upon him[2]. Two years later, in 1584, Muffet finished his De jure et praestantia chemicorum medicamentorum. This document is said to have anticipated Bacon's emphasis on the advancement of learning. That same year, Muffet wrote a letter attacking the London College of Physicians for Papist influences through the lens of his own Puritan beliefs. The following year, however, he was admitted to the College of Physicians, becoming a fellow in February 1588[2]. Later in 1588, Muffet published his Nosomantica Hippocratea, advocating support for the work and writings of Hippocrates. Nine years later, in October 1597, Muffet was elected as a Member of Parliament for Wilton[3]. Three years later, in 1600, Muffet's wife, Jane, died. He married widow Catherine Brown that same year.[5]

Thomas Muffet died at the Bulbridge Farm, in Wilton, Wiltshire on 5 June 1604.

Scientific contributions

Insects

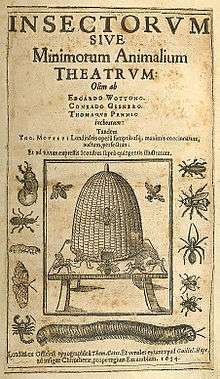

Thomas Muffet first studied silkworms while working in Italy, beginning his continued fascination with arthropods in general, particularly spiders.[6] He is most well known for editing and expanding the work Insectorum sive Minimorum Animalium Theatrum (Theatre of Insects), an illustrated guide to the classification and lives of insects.[1] Although he is popularly believed to have authored it, he merely inherited and furthered its progress toward publication, which would not occur until thirty years after his death. The book contained significant contributions by other scientists, notably the Swiss scientist Conrad Gesner (1516–65).[1] The prime reason it was published posthumously was that the English market for books on natural science was weak at the time. It appears that it was ready for the press in 1589 or 1590. The original title page (unused) is dated 1589. His negotiations with printers in The Hague failed in 1590. The original illustrations were given up as too expensive and replaced with the wood cuts that appear in the 1634 edition. There is the possibility that the same work appears under the name of Théodore Turquet de Mayerne (born Geneva, Switzerland, 1573 – died Chelsea, England, 1655), published in the same year, 1634. Only the introduction of this edition, however, is believed to have been written by de Mayerne.[6]

Good health and nutrition

Muffet's work in nutrition was collected in his book Health's Improvement which was designed more for the layman than for contemporary medical professionals. It contains the first list of British wildfowl, recognizing for the first time the migratory habits of many of them. This book was published even later than Theatrum Insectorum, not until 1655, in an edition edited by Christopher Bennet.[7]

Nursery rhyme connection

It has been suggested that Muffet is the subject of the nursery rhyme 'Little Miss Muffet', which, it is argued refers to an incident with one of his stepchildren. Although the name and subject fit the verse, there is no clear evidence of a connection and the verse was only printed in 1805.[8]

Notes

- Kristensen, Niels P. (1999). "Historical Introduction". In Kristensen, Niels P. (ed.). Lepidoptera, moths and butterflies: Evolution, Systematics and Biogeography. Volume 4, Part 35 of Handbuch der Zoologie:Eine Naturgeschichte der Stämme des Tierreiches. Arthropoda: Insecta. Walter de Gruyter. p. 1. ISBN 978-3-11-015704-8. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- Dawbarn, Frances (2003). "New light on Dr Thomas Moffet: The triple roles of an early modern physician, client, and patronage broker". Medical History (Pre-2012). 47 (1): 3–22. doi:10.1017/S0025727300056337. PMC 1044762. PMID 12617018. ProQuest 229703004.

- "Muffet, Thomas (MFT569T)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- American Council of Learned Societies, Concise dictionary of scientific biography, Scribner's, 2000, ISBN 978-0-684-80631-0, p. 612.

- Lee, Sidney. "Moffett Thomas". Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900. 38.

- Matthew, H. C. G. and Brian Howard Harrison, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, vol. 38, ISBN 978-0-19-861388-6, p. 54

- Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1885). . Dictionary of National Biography. 4. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- I. Opie and P. Opie, The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1951, 2nd edn., 1997), pp. 323–4.

Sources

- Charles C. Gillispie, Ed. Dictionary of Scientific Biography (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1974)

- Margaret Pelling, Medical Conflicts in Early Modern London (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2003)