Thomas Griffith Taylor

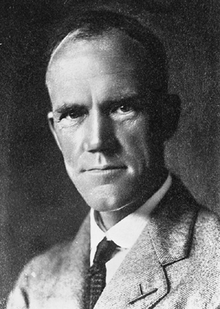

Thomas Griffith "Grif" Taylor (1 December 1880 – 5 November 1963) was an English-born geographer, anthropologist and world explorer. He was a survivor of Captain Robert Scott's Terra Nova Expedition to Antarctica (1910–1913).[1] Taylor was a senior academic geographer at universities in Sydney, Chicago, and Toronto. His writings on geography and race were controversial.

Thomas Griffith Taylor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1 December 1880 Walthamstow, Essex, England |

| Died | 5 November 1963 (aged 82) Manly, New South Wales, Australia |

| Occupation | Geographer, anthropologist, explorer |

| Known for | Terra Nova Expedition |

Early life

Taylor was born in the town of Walthamstow, England, to parents James Taylor, a metallurgical chemist, and Lily Agnes, née Griffiths. Within a year after his birth, the family had moved to Serbia where his father was manager of a copper mine. Three years later, they returned to Britain when his father became director of analytical chemistry for a major steelworks company. In 1893, the family emigrated to New South Wales Australia, where James secured a position as a government metallurgist. Taylor, age 13, attended The King's School in Sydney. He enrolled in arts at the University of Sydney in 1899, later transferring to science, attaining his Bachelor of Science in 1904, and Bachelor of Engineering (mining and metallurgy) in 1905.[2] In 1904 he joined the teaching staff at Newington College.[3] Awarded an 1851 Exhibition scholarship in 1907 to Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where he graduated with a B.A. [Research], Taylor was elected a fellow of the Geological Society, London in 1909. While at Cambridge, he established strong friendships with (Sir) Raymond Priestley, Canada's Charles Wright and the Australian Frank Debenham who all shared his passion for Antarctic exploration and would all travel with him to the Antarctic as part of the Terra Nova Expedition 1910–1913.

Antarctic Expedition

The explorer Robert Falcon Scott contracted Taylor to the Terra Nova Expedition to Antarctica. Scott was looking for an experienced team, and appointed Taylor as Senior Geologist. It was agreed that Taylor would act as representative for the weather service, due to the known effects of Antarctic weather conditions on Australia's climate.[2]

Image: National Library of Australia

Taylor was the leader of the successful geological team, responsible for the first maps and geological interpretations of significant areas of Antarctica. In January 1911, he led an expedition to the coastal area west of McMurdo Sound, in a region between the McMurdo Dry Valleys and the Koettlitz Glacier.[4] He led a second successful expedition in November 1911, this time centering on the Granite Harbour region approximately 50 miles (80 km) north of Butter Point.[5] Meanwhile, Scott led a party of five on a journey to the South Pole, in a race to get there before a rival expedition led by Norwegian Roald Amundsen. They reached the Pole in January 1912, only to find a tent left there by Amundsen containing a dated message informing them that he had reached the Pole 5 weeks earlier. Scott's entire team perished during the return journey, only 11 miles from safety.[2]

Taylor's party was due to be picked up by the Terra Nova supply ship on 15 January 1912, but the ship could not reach them. They waited until 5 February before trekking southward, and were rescued from the ice when they were finally spotted by the ship on 18 February. Taylor left Antarctica in March 1912 on board the Terra Nova, unaware of the fate of Scott's polar party. Geological specimens from both Western Mountains expeditions were retrieved by Terra Nova in January 1913. Later that year, Taylor was awarded the King's Polar medal and made a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society of London.

Taylor's physiographical and geomorphological Antarctic research earned him a doctorate (D.Sc) from the University of Sydney in 1916.[2] He was made Associate Professor of Geography in 1921 becoming the founding head of the Department of Geography at the university. Taylor did not completely agree with the Australian Government's White Australia policy, which sought to limit immigrants to whites only. Taylor argued that Australia's agricultural resources were limited, and that this, together with other environmental factors, meant that Australia would not be able to support the population goal of 100 million which some optimistically predicted. Moreover, he claimed that due to climatic factors, the interior of Australia would be best settled by broad-headed Mongoloids who were better adapted to the environment. He was severely criticised as unpatriotic for his views on Australia's future development. A textbook he had written containing these views was banned from schools by the Western Australian education authority. Taylor was a proponent of environmental determinism with the view that "physical environment determines culture." In 1927, he became the first President of the Geographical Society of New South Wales.

Environment, race, and migration

Taylor wrote many books about the effects of the environment in shaping race. He also wrote extensively about migration of the races. Taylor saw theories that explained the genealogy of races as beginning in Africa and then expanding out through the world and evolving in positive ways as antiquated thinking from the 19th century. In his 1937 book Environment, Race, and Migration, Taylor outlines a theory that the "Mongolian" race is the race truest to their past in the hearth of modern humans: Central Asia. Australoid and Negroid races were the first to branch off during humanity's evolution from the Neanderthal and were racially adapted to live in the world's margins. The Negrito race was never related to Neanderthals, and were thus likely developed more directly from apes. "During the million years of Post-Pliocene" time, humans were forced to migrate during four major migrations related to the expansion of the "Great Ice Sheet." As humans moved to different areas of the world they adapted to the environment they encountered. Taylor openly disagrees with Wegener's theory of Continental Drift, writing that the human races evidently migrated into world's regions separately and over time. They moved out over the world, the world didn't move them. (Note: this was written in a period before knowledge of plate tectonics). Taylor links skin pigment to temperature and collects extensive data from the period on geology, topology, meteorology, and anthropology. Taylor saw geography in a synthesising role between explanations of the physical world and the diffusion and evolution of the human species.

"The fittest tribes evolve and survive in the most stimulating regions; i.e., where living is not so hard as to stunt mental development, and not so easy as to encourage sloth and loss of initiative. The least fit are ultimately crowded out into the deserts, the tropical jungles, or the rugged mountains."[6]

In regards to anthropology, Taylor looks at records of hair texture and size, nose size, ear size, cephalic indices, skin color, and height. He links sexual attraction amongst different races to evolved and diverged cultural preferences for beauty. Taylor comes up with the theory of the "tri-peninsular world", in which the world is divided into three peninsulas descending south from a common point in the Arctic (Americas, Europe and Africa, Asia and Australia). In these peninsulas, Taylor finds climate and race similarities. In regards to racial variation within smaller regions, Taylor offers this passage about Europe's races:

"The Eur-African peninsula is now considered. Here the racial types have been fairly well investigated. We know that the term "European" has no value as an ethnological distinction. Thus the Savoyard of eastern France is akin to the wild tribes of the Pamirs, but not to the primitive peoples of the Dordogne only two hundred miles to the west. The Corsican is much more nearly allied to the Cornishman than to the Italian peoples of the adjacent Alps. In Wales, we are told, there are small groups still essentially allied to Neanderthal man."[7]

The most suitable parts of the world for habitation are, according to Taylor, in Europe, Western Siberia, the Americas, and Eastern China. These are the places that, if not already overcrowded, are where the world's masses must one day move into. Places least adaptable to European styles of agriculture and settlement are considered by Taylor "useless". In the final section of the book Taylor lays out the possibilities of future expansion of the white race, which he sees as the only race which will expand. Though he voices that no Europeans would wish to extinguish or force native people from their lands, "these primitive people are doomed to extinction..." Whites would eventually settle all "useful lands."

Taylor disagreed with theories that put the Nordic race as the apotheosis of mankind. By his theory, Asiatic races would be the most pure. He gives great accolades to the Chinese race. He links Europe's historical accession in the global sphere to command of the seas and easy access to plentiful surface coal.

Taylor takes a seemingly contradictory viewpoint by both decrying miscegenation and saying that white Australian women who married Chinese men were OK to do so. Mixing of more advanced races was, ostensibly, acceptable, while miscegenation with more primitive races was to be abhorred.

All citations are from the book Environment, Race, and Migration.[8]

Move to North America and return to Australia

In 1929, he accepted a post as Senior Professor of Geography at the University of Chicago. In 1936 he moved to the University of Toronto founding the Geography department there. During the 1930s, Taylor was co-editor of the German journal on racial studies Zeitschrift fur Rassenkunde, he felt that American scholars were concerned too little with racial classification, and showed an affinity to the works of Baron von Eickstedt.[8] In 1940 he was elected president of the Association of American Geographers, the first non-American to be elected to the post. Taylor was close to Isaiah Bowman who shared similar interests in population and settlement studies. After retiring from his post at the university in 1951, he returned to Sydney. In 1954 he was elected to the Australian Academy of Science, the only geographer to receive this distinction. In 1958 he published his autobiography "Journeyman Taylor", and in 1959 was named the first President of the Institute of Australian Geographers.

Personal life and legacy

Taylor died in the Sydney suburb of Manly on 5 November 1963, aged 82.[2]

In 1976 he was honoured on a postage stamp bearing his portrait issued by Australia Post.[9] In 2001, an Australian postage stamp commemorated Taylor and fellow explorer Douglas Mawson.[1]

Taylor was the author of some 20 books and 200 scientific articles.

He was the brother-in-law of fellow Terra Nova expedition members Raymond Priestley and C.S. Wright.

References

- Huxley, John (17 September 2008). "Eccentric explorer taken out of the shadows". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 17 September 2008.

- "Taylor, Thomas Griffith (1880–1963)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. 2006. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- Wood, Michael J. (2008). "Meteorologist's profile – Thomas Griffith Taylor (1880–1963)". Weather. 63 (12): 361–364. doi:10.1002/wea.242.

- See Scott's instructions, SLE, Vol. II, pp. 184–85.

- Scott's instructions; SLE, Vol. II, pp. 222–23.

- Taylor, Thomas Griffith (1880–1963) (1937). Environment, Race, and Migration. University of Chicago Press Chicago, Illinois. p. 6.

- Taylor, Thomas Griffith (1880–1963) (1937). Environment, Race, and Migration. University of Chicago Press Chicago, Illinois. p. 9.

- Taylor, Thomas Griffith (1880–1963) (1937). Environment, Race, and Migration. University of Chicago Press Chicago, Illinois.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thomas Griffith Taylor. |