This Misery of Boots

This Misery of Boots is a 1907 political tract by H. G. Wells advocating socialism. Published by the Fabian Society, This Misery of Boots is the expansion of a 1905 essay with the same name. Its five chapters condemn private property in land and means of production and calls for their expropriation by the state "not for profit, but for service."[1]

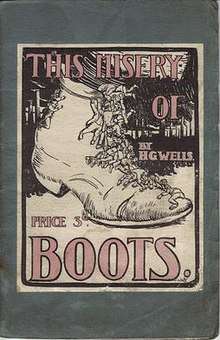

First Edition Cover | |

| Author | H. G. Wells |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Tract |

| Publisher | Fabian Society |

Publication date | 1907 |

| Media type | Print (Paperback) |

| Pages | 42 |

| Preceded by | Socialism and the Family |

| Followed by | New Worlds for Old (H. G. Wells) |

Synopsis

Chapter 1: The World as Boots and Superstructure

Wells's point of departure is a reminiscence of a conversation with "a realistic novelist . . . a man from whom hope had departed." An encounter with a limping tramp spurs a discussion of the 10–20% of the British population that suffers from "this misery of the boot." They classify the various sources of discomfort (bad material, bad fit, bad condition, various sorts of chafe, the wear of the sole, splitting and leaks, etc.) and agree that most boots are a constant source of “stress, giving pain and discomfort, causing trouble, causing anxiety.” But Wells's friend finds the subject too depressing to continue: “It does not do to think about boots,[2] he exclaims.

Chapter 2: People Whose Boots Don’t Hurt Them

Wells, however, disagrees. "[A]ll these miseries are preventable miseries, which it lies in the power of men to cure," he proclaims, and cites another friend who has achieved prosperity and no longer endures "the miseries of boots" but now suffers all the more, albeit vicariously, from the miseries of others, because he no longer believes that they are "in the very nature of things." He blames the statesmen who "ought to have foreseen and prevented this." Wells exhorts his readers not to "be humbugged for a moment into believing that this is the dingy lot of all mankind. . . . Don't say for a moment: 'Such is life.'"[3]

Chapter 3: At This Point a Dispute Arises

Wells says he is not advocating a "childish and impossible equality," but insisting that "There is enough good leather in the world to make good sightly boots and shoes for all who need them, enough men at leisure and enough power and machinery to do all the work required, enough unemployed intelligence to organise the shoemaking and shoe distribution for everybody." What prevents this is "this institution of Private Property in land and naturally produced things," the "claim and profit" of "land-owners, cattle-owners, house-owners, owners of all sorts." The solution lies in "refusing to have private property in all these universally necessary things." Wells endorses expropriation by "the State" and the administration of land, railways, shipping, and businesses "not for profit, but for service."[4]

Chapter 4: Is Socialism Possible?

Private property in land and "many things of general utility" is no more "necessary and unavoidable" than "private property in our fellow-creatures, or private property in bridges and roads." Wells denies any owner's right to compensation, but adds that "it is quite conceivable that we may partially compensate the property owners and make all sorts of mitigating arrangements." Wells denies that the rich will uniformly oppose socialism and asserts that many of this class will see that they would be "happier and more comfortable in a Socialistic state of affairs." It is, rather, "the ignorance, the want of courage, and the stupid want of imagination of the very poor" that is more likely to "obstruct the way to Socialism."[5]

Chapter 5: Socialism Means Revolution

Wells argues that socialism requires "a complete change, a break with history. . . . The whole system has to be changed." "If you demand less than that, if you are not prepared to struggle for that, you are not really a Socialist." The essential problem is to enlist "the self-abnegation, the enthusiasm, and the loyal cooperation of great masses of people." To that end, Wells calls on socialists to persuade others, organize their movement, and clarify their beliefs. "For us, as for the early Christians, preaching our gospel is the supreme duty." His final piece of advice: "Cling to the simple essential idea of Socialism, which is the abolition of private property in anything but what a man has earned or made."[6]

Background

Wells had considered himself a socialist since the mid-1880s, but his socialism was one marked by "a unique personal bias" and "is always projected toward a world order."[7] In 1886-1889 Wells had undertaken a study of the classic utopian writings of the Western tradition, and in the 1890s he integrated his socialistic beliefs with his views on evolution. He read psychology to seek practical insights. In the first decade of the twentieth century Wells refined his views, writing many essays and four book-length works promoting socialism: Mankind in the Making (1903), A Modern Utopia (1905), Socialism and the Family (1906), and New Worlds for Old (1908).[8] Wells joined the Fabian Society on March 13, 1903.[9] He remained a member until 1908.

Redaction

Wells had published an article entitled The Misery of Boots in Vol. 7, No. 27, of the Independent Review (December 1905), a magazine founded in 1904. He worked this up into a talk delivered to the Fabian Society on 12 January 1906. Despite its implicit criticism of Sidney and Beatrice Webb as engaged merely in "odd little jobbing about municipal gas and water,"[10] Wells's talk was received with enthusiasm, and it was reprinted in 1907 as a Fabian pamphlet.[11] But its publication was delayed because Wells was engaged in an effort to wrest control of the Fabian Society away from the Webbs, among others, and some of his remarks in This Misery of Boots were perceived as "sneers" at the Webbs.[12]

Reception

George Bernard Shaw wrote to Sidney Webb: "Do not underrate Wells. What you said the other day about his article in the Independent Review being a mere piece of journalism suggested to me that you did not appreciate the effect his writing produces on the imagination of the movement."[13]

This Misery of Boots is often described as "brilliant"[14] and has often been reprinted.

References

- H.G. Wells, This Misery of Boots (London: The Fabian Society, 1907), Ch. 3.

- H.G. Wells, This Misery of Boots (London: The Fabian Society, 1907), Ch. 1.

- H.G. Wells, This Misery of Boots (London: The Fabian Society, 1907), Ch. 2.

- H.G. Wells, This Misery of Boots (London: The Fabian Society, 1907), Ch. 3. William J. Hyde calls Wells's view of property "the somewhat conventional socialist's view." William J. Hyde, "The Socialism of H.G. Wells in the Early Twentieth Century," Journal of the History of Ideas 17.2 (April 1956).

- H.G. Wells, This Misery of Boots (London: The Fabian Society, 1907), Ch. 4.

- H.G. Wells, This Misery of Boots (London: The Fabian Society, 1907), Ch. 5.

- William J. Hyde, "The Socialism of H.G. Wells in the Early Twentieth Century," Journal of the History of Ideas 17.2 (April 1956), p. 217.

- David C. Smith, H.G. Wells: Desperately Mortal: A Biography (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1986), pp. 91-102.

- Michael Sherborne, H.G. Wells: Another Kind of Life (Peter Owen, 2010), p. 159.

- H.G. Wells, This Misery of Boots (London: The Fabian Society, 1907), Ch. 5.

- Michael Sherborne, H.G. Wells: Another Kind of Life (Peter Owen, 2010), p. 173.

- Norman and Jeanne MacKenzie, H.G. Wells" A Biography (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1973), pp. 210–11.

- Letter of November 25, 1906, quoted in Norman and Jeanne MacKenzie, H.G. Wells" A Biography (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1973), pp. 213–14.

- See, for example, J. Huntington, The H.G. Wells Reader: A Complete Anthology from Science Fiction to Social Satire (Rowman & Littlefield, 2003).