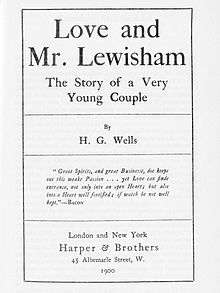

Love and Mr Lewisham

Love and Mr Lewisham (subtitled "The Story of a Very Young Couple") is a 1900 novel set in the 1880s by H. G. Wells. It was among his first fictional writings outside the science fiction genre. Wells took considerable pains over the manuscript and said that "the writing was an altogether more serious undertaking than I have ever done before."[1] He later included it in a 1933 anthology, Stories of Men and Women in Love.

| |

| Author | H. G. Wells |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publisher | Harper Brothers |

Publication date | 1900 |

| OCLC | 4186517 |

| Text | Love and Mr Lewisham at Wikisource |

Events in the novel closely resemble events in Wells's own life. According to Geoffrey H. Wells: "referring to the question of autobiography in fiction, H. G. Wells has somewhere made a remark to the effect that it is not so much what one has done that counts, as where one has been, and the truth of that statement is particularly evident in this novel. ... Both Mr Lewisham and Mr Wells were at the age of eighteen, assistant masters at country schools, and that three years later both were commencing their third year at The Normal School of Science, South Kensington, as teachers in training under Thomas Henry Huxley. The account of the school, of the students there and of their social life and interests, may be taken as true descriptions of those things during the period 1883-1886."[2]

Plot

At the beginning of the novel, Mr Lewisham is an 18-year-old teacher at a boys' school in Sussex, earning forty pounds a year. He meets and falls in love with Ethel Henderson, who is paying a visit to relatives. His involvement with her makes him lose his position, but he is unable to find her when he moves to London.

After a two-and-a-half-year break in the action, Mr Lewisham is in his third year of study at the Normal School of Science in South Kensington. He has become a socialist, declaring his politics with a red tie, and is an object of interest to Alice Heydinger, an older student. However, chance brings him together again with his first love at a séance. Ethel's stepfather, Mr Chaffery, is a spiritualist charlatan, and Mr Lewisham is determined to extricate her from association with Chaffery's dishonesty. They marry, and Mr Lewisham is forced to abandon his plans for a brilliant scientific career followed by a political ascent. When Chaffrey absconds to the Continent with money he has embezzled from his clients, Lewisham agrees to move into his shabby Clapham house to look after Ethel and Ethel's elderly mother (Chaffrey's abandoned wife). Wells's friend Sir Richard Gregory wrote to him after reading the novel: "I cannot get that poor devil Lewisham out of my mind head, and I wish I had an address, for I would go to him and rescue him from the miserable life in which you leave him."[3]

Reception

Love and Mr Lewisham was well received, and Charles Masterman told Wells that he believed that along with Kipps, it was the novel most likely to endure.[4] Sir Richard Gregory compared the novel to Thomas Hardy's Jude the Obscure.[5]

Happily, Mr Wells is a man of varying moods. ... ... Like Dickens, with whom he has much more in common than Gissing had, he shows a happier touch in revealing the merits of the meek and lowly than in exposing the failings of the rich and noble. Vivid as is the gift of satire which he exhibits in other directions, he cannot get a scantling of truth and sharpness into his caricatures of overbearing village squires and supercilious ladies of the manor. But how fresh and clear, on the other hand, is the picture of the poor rustic scholar in 'Love and Mr Lewisham'! How tender the humor, and how light and telling the touch with which the story of his struggle between love and ambition is depicted![6]

More recent critics have also praised the novel. Richard Higgins claims the novel elaborates a "close examination of the relationship between class and the emotions", adding that "these emotions have much to add to conventional class analysis. Many of these emotions are more prosaic than we have been accustomed to observe—more passive frustration, for example, than class rage."[7] And Adam Roberts argues that the novel uses Chaffrey's fake séance as an expressive metaphor for a Wellsian engagement with questions of sexual desire and disillusionment.[8]

References

- Notes

- Smith (1986), p. 208.

- Wells, Geoffrey H. (1926), The Works of H G Wells 1887-1925 London: Routledge, pp.15-16

- Mackenzie, Norman and Jeanne (1973), The Time Traveller: the Life of H.G. Wells London. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, p. 152.

- Smith (1986), p. 202.

- Smith (1986), p. 208.

- "The Ideas of Mr H. G. Wells". The Quarterly Review. 208: 472–490. April 1908; quote pp. 487–488

- Higgins, Richard, 'Feeling Like a Clerk in H G Wells', Victorian Studies 50:3 (2008), p.458

- Roberts, Adam (2017), 'Love and Mr Lewisham', Wells at the World's End

- Sources

- Smith, David C. (1986). H.G. Wells: Desperately Mortal: A Biography. New Haven and London: Yale University Press

External links