Theophilus Hastings, 7th Earl of Huntingdon

Theophilus Hastings, 7th Earl of Huntingdon (10 December 1650 – 30 May 1701) was a 17th-century English politician and Jacobite. Once the leading political power in Leicestershire, his family had declined in influence; regaining that position became his primary ambition and drove his political choices. During the 1679 to 1681 Exclusion Crisis, he supported the removal from the succession of the Catholic heir, James, Duke of York, before switching allegiance in 1681.

The Earl of Huntingdon | |

|---|---|

Theophilus Hastings, 7th Earl of Huntingdon | |

| Lord Lieutenant of Leicestershire | |

| In office 11 August 1687 – 6 April 1689 | |

| Preceded by | Earl of Rutland |

| Succeeded by | Earl of Rutland |

| Lord Lieutenant of Derbyshire | |

| In office 23 December 1687 – 16 May 1689 | |

| Preceded by | Earl of Scarsdale |

| Succeeded by | Duke of Devonshire |

| Colonel, Earl of Huntingdon's Foot | |

| In office 1685–1688 | |

| Preceded by | New unit |

| Succeeded by | Ferdinando Hastings |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 10 December 1650 |

| Died | 30 May 1701 (aged 50) |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Lewis (1654–1688, her death) Mary Fowler (1664–1701, his death) |

| Children | 3 sons, 5 daughters (8 others died young) |

James succeeded as king in 1685 with widespread support but this collapsed when his religious measures and the methods used to enforce them seemed to undermine the legal system and the Church of England. By the end of 1687, Huntingdon was one of the few non-Catholics who continued to actively implement his policies.

While changing sides was common in this period, and after the November 1688 Glorious Revolution, a sizeable minority continued to view James as the legitimate monarch, primacy of the Church of England was non-negotiable. Huntingdon was considered to have actively persecuted his own church, a distinction that damaged his reputation among his contemporaries.

One of 30 individuals excluded from the 1690 Act of Grace, he lost his offices but continued to attend the House of Lords and remained a committed Jacobite. He was arrested and charged with treason in 1692, although charges were later dropped; shortly before his death in May 1701, he was one of five peers who voted against the 1701 Act of Settlement barring Catholics from the throne.

Early life

Theophilus Hasting was born on 10 December 1650, fourth son of Ferdinando Hastings, 6th Earl of Huntingdon and his wife Lucy. His three elder brothers died before his birth and he succeeded his father in 1656 at the age of five.

Once the pre-eminent family in Leicestershire, the Hastings declined in influence after decades of over-spending and losses incurred during the 1642 to 1651 Civil Wars.[1] The 6th Earl remained neutral but his younger brother Henry commanded the Royalist garrison holding the family seat of Ashby de la Zouch Castle. This was partially destroyed by Parliamentary forces during the 1647 to 1648 Second English Civil War and Henry escaped abroad.[2]

The family relocated to the nearby Donington Hall estate, where Hastings was educated by his mother and his uncle Henry, who returned from exile in 1660. As a reward for his loyalty, Charles II created him Baron Loughborough and Lord Lieutenant of Leicestershire, an office held by the Hastings family almost continuously between 1550 and 1642. When he died in 1667, John Manners, 8th Earl of Rutland took his place and regaining this position became Hastings' over-riding ambition.[3]

In 1672, Hastings married Elizabeth Lewis (died 1688), whose sister Mary (died 1684) was wife of the Earl of Scarsdale; the two were co-heiresses of Sir John Lewis, a wealthy merchant who owned Ledstone Hall, in West Yorkshire.[4] They had nine children, only two of whom survived to adulthood; George, 8th Earl of Huntingdon (1677-1704) and Elizabeth (1682-1739), a noted supporter of women's education.[5]

Elizabeth died in 1688 and two years later, Hastings married Mary Fowler (1664–1723), wealthy widow of Thomas Needham, 6th Viscount Kilmorey (1659-1687).[6] They had two sons and four surviving daughters; Ann (1691-1755), Catherine (1692-1739), Frances (1693-1750), Theophilus, 9th Earl of Huntingdon (1696-1746), Margaret (1699-1768) and Ferdinando (1699-1726).[7]

Career

Hastings took his seat in the Lords and was a reliable supporter of the Crown until 1677, when the 9th Earl of Rutland succeeded his father as Lord Lieutenant. The Manners family supported Parliament in the Civil Wars, and Hastings was frustrated by a perceived lack of gratitude for his family's service.[8]

He joined the faction led by the Earl of Shaftesbury, who opposed Charles' efforts to rule without Parliament and campaigned against 'Popery and arbitrary government.' The potential succession of the Catholic, pro-French Duke of York was seen as another step towards absolutism and led to the 1679–1681 Exclusion Crisis. Hastings became a prominent supporter; at a public dinner in 1679, he proposed a toast to the Protestant Duke of Monmouth, viewed as an alternative to James, and 'confusion to Popery', prompting a heated exchange with other guests.[9]

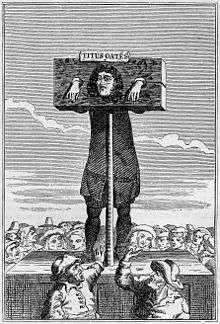

During the anti-Catholic campaign known as the Popish Plot in 1680, Hastings voted for the execution of Viscount Stafford, as did seven of eight members of Stafford's own family.[10] It led to the execution of 22 alleged conspirators and caused widespread unrest; in August 1681, Titus Oates, source of the accusations, accused the Queen of conspiring to poison Charles.[11]

This was seen as going too far and many now withdrew their support, including Hastings; banned from Court in 1680, he was restored to favour in October 1681. In February 1682, he paid Scarsdale £4,500 for his post as Captain of the Honourable Band of Gentlemen Pensioners, a ceremonial bodyguard with close access to the monarch.[9] He was appointed to the Privy Council in 1683 and when James became king in February 1685, he was made Justice in Eyre and colonel of an infantry regiment.[12]

At the start of his reign, James had widespread backing, inheriting a legislature so dominated by his supporters it became known as the Loyal Parliament. Memories of the 1638 to 1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms meant the majority feared the consequences of removing the 'natural' heir; this caused the rapid collapse of the Monmouth and Argyll rebellions in June 1685. However, the Church of England and the legal system were key elements of a stable society; James' religious policies undermined the former, attempts to enforce them attacked the latter. When Parliament refused to pass his measures, it was suspended in November 1685 and thereafter he ruled by decree; the principle was accepted, the scope and approach were not, and judges who opposed his interpretation were dismissed.[13]

This forced James to rely on a few loyalists, one being Hastings, who was made a member of the Commission for Ecclesiastical Causes in July 1686. A number of people, including his first wife, accused him of being a secret Catholic; if true, this was controversial, since the Commission was set up to enforce compliance on the Church of England. Suspicions increased when he was exempted from the 1678 Test Act requiring office holders swear to uphold 'the Protestant religion.'[14]

In late 1687, James tried to ensure a Parliament that would vote for his Declaration of Indulgence; only those who confirmed their support for repealing the Test Act would be allowed to stand for election as Member of Parliament.[15] Lord-Lieutenants were to administer the so-called 'Three Questions'; many resigned rather than do so, including Scarsdale, who Huntingdon replaced as Lord Lieutenant of Derbyshire.[16]

Combined with the trial of the Seven Anglican bishops for seditious libel in June 1688, James' policies now seemed to go beyond tolerance for Catholicism and Nonconformists and into an assault on the Church of England. Wild celebrations when the bishops were acquitted made it seem only his deposition could prevent widespread civil unrest and the vast majority of his Tory supporters abandoned him. The seven signatories of the Invitation to William asking him to assume the English throne included representatives from the Tories, the Whigs, the Church and the Navy.[17]

During the Glorious Revolution in November 1688, Hastings and his regiment were sent to secure Plymouth; on arrival, he was arrested by its governor, the Earl of Bath, who declared for William.[18] He was released on 26 December, two days after his wife died in childbirth; as one of thirty individuals exempted from the 1690 Act of Grace, he forfeited his offices although he continued to attend the Lords.[19] He initially retained some local influence and in 1690, his support helped elect Sir Edward Abney, Tory candidate for Leicester. Thereafter the borough was dominated by the Manners family and he withdrew from active politics.[20]

As a committed Jacobite, Hastings was arrested during the 1692 invasion scare, allegedly because his stables were 'full of horses'.[9] After the March 1696 Jacobite assassination plot, he voted against the execution of Sir John Fenwick and refused to take the loyalty oath imposed by Parliament.[21] One of his last acts was to vote against the Act of Settlement that disinherited the Catholic Stuart exiles in favour of the Protestant Sophia of Hanover.[22]

His later years were dominated by a long-running legal dispute with his eldest son over his first wife's estates, which was settled only after his death.[23] He died in London on 30 May 1701 and was succeeded by George, who served in the Low Countries during the War of the Spanish Succession and died of fever in 1705.[24]

Assessment

Although Hasting was a minor political figure and not unusual in changing sides, on the rare occasions he is mentioned by historians, he is described as a 'facile instrument of the Stuarts,' a 'turncoat' or 'outright renegade.'[25]

17th century England was an intensely hierarchical society; many who supported James in 1685 and beyond did so because they considered him king due to birth and divine favour. His personal failings could not change this and five of the Seven Bishops later refused to swear allegiance to William on these grounds, which led to the Nonjuring schism.[26] This was also the justification used by the five peers who voted against the Act of Settlement, two of whom were Hasting and Scarsdale.[27]

Hostility to Catholicism arose from the wider international context, where French expansion under Louis XIV threatened the Dutch Republic and other parts of Protestant Europe. In October 1685, 200,000-400,000 French Protestants were forced into exile by the Edict of Fontainebleau, 40,000 of whom settled in London.[28] Combined with the killing of around 2,000 Vaudois Protestants in 1686, it made attempts by James to impose religious tolerance ill-timed.[29]

The 1678 Test Act required public officials to swear to uphold the primacy of the Protestant religion and Church of England, as did James at his coronation; most considered this incompatible with legal 'tolerance' for Catholics or Non-Conformists.[30] In practice, these groups were allowed to worship in private, and many of them viewed the measures as bringing unwelcome publicity. When James nominated the Non-Conformist Sir John Shorter as Lord Mayor of London, he insisted on complying with the Test Act, due to a 'distrust of the King's favour...thus encouraging that which His Majesties whole Endeavours were intended to disannull.'[31]

Scarsdale and many others resigned their offices in protest, while army officers including Churchill and Trelawny, formed the Association of Protestant Officers to oppose them.[32] Hastings signed the warrant committing the bishops to the Tower, when even hardline supporters like Lord Chancellor Jeffreys opposed their prosecution; it was this distinction that was held against him.[33]

His reputation for inconsistency was increased during the 1689 Convention Parliament, when he voted first against a Regency, then with the Jacobite loyalists, and finally in favour of making William king.[34] Historian Peter Walker argues all other issues were secondary to restoring his family's position, but 'continued loyalty to James in his last years suggests (he) was not a man bereft of principle.'[35]

References

- Walker 1977, p. 61.

- Curtis 1831, p. 88.

- Walker 1977, p. 62.

- Historic England. "Ledston Hall & Gardens (1001221)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Livingstone 1998, p. 87.

- "Thomas Needham, 6th Viscount Kilmorey". The Peerage. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "Theophilus Hastings, 7th Earl of Huntingdon". The Peerage. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- Walker 1977, p. 64.

- Patterson, 2004 & OnlineDNB.

- Kenyon 1972, p. 231.

- Tapsell 2007, p. 90.

- Dalton 1896, pp. 414-415.

- Miller 1978, pp. 156-157.

- Walker 1956, p. 81.

- Walker 1956, pp. 63-68.

- Miller 2012, pp. 127–129.

- Harris 2006, p. 235-236.

- Childs 1986, p. 191.

- Belsham 1802, p. 187.

- Cruickshanks, 1983 & Online.

- Vallance 2005, pp. 201–2.

- Walker 1977, p. 66.

- House of Commons 1803, p. 237.

- Holmes 2009, p. 228.

- Western 1972, pp. 120,215.

- Harris 2006, pp. 179-181.

- Volume 16, 22 May 1701. "Limitation of the Crown, Bill". British History Online. House of Lords Journal. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- Spielvogel 2014, p. 410.

- Bosher 1994, pp. 6-8.

- Harris 2006, pp. 98-99.

- Harris 2006, p. 234.

- Holmes 2009, p. 136.

- Halliday, 2009 & OxfordDNBOnline.

- Jones & Jones 1986, pp. 86–87.

- Walker 1977, pp. 70-71.

Sources

- Belsham, William (1802). Appendix to the History of Great Britain, from the Revolution, 1688, to the Treaty of Amiens, A.D. 1802 Volume 1 (2014 ed.). Book on Demand Ltd. ISBN 5518964153.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bosher, JF (February 1994). "The Franco-Catholic Danger, 1660–1715". History. 79 (255): 5–30. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1994.tb01587.x. JSTOR 24421929.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curtis, John (1831). A Topographical History of the County of Leicester (2017 ed.). Forgotten Books. ISBN 1528215095.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Childs, John (1986). Army, James II and the Glorious Revolution. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719006880.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cruickshanks, E (ed), Hayton, D (ed) (1983). The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1690-1715 (Online ed.). Haynes Publishing. ISBN 978-0436192746.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dalton, Charles (1896). English army lists and commission registers, 1661-1714. Government and General Publishers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halliday, Paul (2009). Jeffreys, George, first Baron Jeffreys (1645–1689) (Online ed.). Oxford DNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14702.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harris, Tim (2006). Revolution: The Great Crisis of the British Monarchy, 1685–1720. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9759-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holmes, Richard (2009). Marlborough; England's Fragile Genius. Harper Press. ISBN 978-0007225729.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Journals of the House of Commons, Volume 11; 1693-1697. House of Commons. 1803.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Clyve; Jones, David (1986). Peers, Politics and Power: House of Lords, 1603-1911. Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 0907628788.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kenyon, JP (1972). Popish Plot. William Heinemann Ltd. ISBN 978-0434388509.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Livingstone, Neil (1998). Yun, Lee Too (ed.). Pedagogy and Power: Rhetorics of Classical Learning. CUP. ISBN 978-0521594356.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miller, John (1978). James II; A study in kingship. Menthuen. ISBN 978-0413652904.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Patterson, Catherine F (2004). Hastings, Theophilus, seventh earl of Huntingdon (Online ed.). Oxford DNB.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spielvogel, Jackson J (1980). Western Civilization. Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 1285436407.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tapsell, Peter (2007). The Personal Rule of Charles II, 1681-85: Politics and Religion in an Age of Absolutism. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1843833055.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vallance, Edward (2005). Revolutionary England and the National Covenant: State Oaths, Protestantism, and the Political Nation, 1553-1682. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-118-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walker, Peter (1956). James II and the Three Questions: Religious Toleration and the Landed Classes, 1687-1688 (2010 ed.). Verlag Peter Lang. pp. 62–64. ISBN 978-3039119271.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walker, Peter (1977). "The political career of Theophilus Hastings (1650-1701), 7th Earl of Huntingdon". Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society (71).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Western, JR (1972). Monarchy and revolution: the English State in the 1680. Littlehampton Book Services Ltd. ISBN 0713732806.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- "Theophilus Hastings, 7th Earl of Huntingdon". The Peerage. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- Volume 16, 22 May 1701. "Limitation of the Crown, Bill". British History Online. House of Lords Journal. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- "Thomas Needham, 6th Viscount Kilmorey". The Peerage. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Historic England. "Ledston Hall & Gardens (1001221)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by The Earl of Chesterfield |

Justice in Eyre south of the Trent 1686–1689 |

Succeeded by The Lord Lovelace |

| Military offices | ||

| New regiment | Colonel, Earl of Huntingdon's Foot 1685–1688 |

Succeeded by Ferdinando Hastings |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by The 2nd Earl of Denbigh |

Custos Rotulorum of Leicestershire 1675–1680 |

Succeeded by The 3rd Earl of Denbigh |

| Preceded by The 3rd Earl of Denbigh |

Custos Rotulorum of Leicestershire 1681–1689 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Stamford |

| Preceded by The Earl of Scarsdale |

Captain of the Gentlemen Pensioners 1682–1689 |

Succeeded by The Lord Lovelace |

| Lord Lieutenant of Derbyshire 1687–1688 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Devonshire | |

| Preceded by The Earl of Rutland |

Lord Lieutenant of Leicestershire 1687–1689 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Rutland |

| Peerage of England | ||

| Preceded by Ferdinando Hastings |

Earl of Huntingdon 1656–1701 |

Succeeded by George Hastings |