The Three Brothers (jewel)

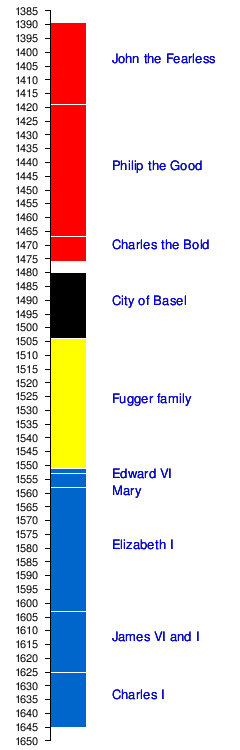

The Three Brothers (also known as The Three Brethren, German Die Drei Brüder or French Les Trois Frères) was a piece of jewellery created in the late 14th century that is known for having been owned by a number of important medieval figures, among them Duke John the Fearless of Burgundy, the German banker Jakob Fugger, Queen Elizabeth I, and King James VI and I. It was part of the English Crown Jewels from 1551 to 1644, when it was possibly sold by Henrietta Maria, wife of Charles I. Its whereabouts after 1645 remain unknown.[1]

| The Three Brothers | |

|---|---|

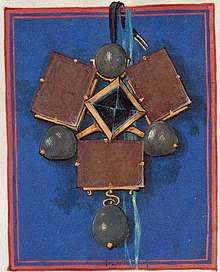

Miniature painting of the Three Brothers jewel, commissioned by the city of Basel, c.1500 | |

| Material | Spinels, pearls, diamond, gold |

| Weight | ~300 carats (60 g) total |

| Created | 1389 |

| Place | Paris, France |

| Present location | Unknown since 1645 |

Description

Despite its history, the jewel remained almost unchanged over more than 250 years. Made as a shoulder clasp or pendant, it consisted of three rectangular red spinels (then known as balas rubies) of 70 carat each in a triangular arrangement, separated by three round white pearls of 10-20 carat each, with another pearl suspended from the lowest spinel. The middle of the pendant was a deep blue diamond weighing about 30 carats,[2] in the shape of a pyramid, octahedron, or regular trisoctahedron.[3] As there is little evidence for diamond cutting before 1400, its jeweller had likely merely squared off (described as "quarré" on the original invoice) its natural form.[4]

When it makes its first appearance in an inventory—that of Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy in 1419—it is described as:

A very fine and rich buckle, adorned in the middle with a very big pointed diamond, and around this are three fine square balas stones called the three brothers, and three sizable fine pearls inbetween these. Under this buckle hangs a very large fine pearl in the shape of a pear.[5]

In 1587 the Three Brothers are listed among jewels delivered to Elizabethan courtier Mary Radcliffe and described as:

A faier flower with three great ballaces and in the middest a great pointed diamonde and three great pearles sett with a faier great pendaunt pearle. Called the Brethren.[1]

Early history

The Three Brothers was commissioned by Duke John the Fearless of Burgundy in the late 1380s, and was one of the most precious treasures of the House of Burgundy.[1] It was created by Parisian goldsmith Herman Ruissel in 1389, a bill and receipt of which still exist in the Côte-d'Or Departmental Archives in Dijon.[6] After receiving it in the 1390s, Duke John pawned the jewel in 1412, but redeemed it at some point before 1419. When the Duke—who was a major figure in the Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War over the French throne—was assassinated during a parley with the French dauphin (the future King Charles VII) in 1419, the Brothers were passed down to his son Philip the Good.[7]

Timeline of owners

The jewel remained in Burgundy during Philip's reign, and on his death in 1467, was inherited by his son Charles the Bold. Charles commanded one of the most powerful armies of his time, and travelled to battles with an array of priceless artifacts as talismans, including carpets belonging to Alexander the Great, the bones of saints, the enormous Sancy diamond, and the Three Brothers.[8][9]:53 In his conflict with the Old Swiss Confederacy during the Burgundian Wars, Charles suffered a catastrophic rout in March 1476, when he was attacked outside the village of Concise in the Battle of Grandson. Forced to flee in haste, Charles left behind his artillery and an immense booty, including his silver bath, the ducal seal, and the Brothers, all of which were looted from his tent by the confederate army.[10] The pendant was eventually sold to the magistrates of the city of Basel, who had the piece assessed and commissioned a watercolour miniature of it, which provides the earliest visual record of the Brothers (today in the Basel Historical Museum).[11] The jewel disappeared from view during the next years, as the magistrates feared that the House of Habsburg—inheritors of the Duchy of Burgundy—would reclaim goods that they considered as having been stolen from Charles.[9]:53 The city at last put the jewel on the market in 1502.[1]

In 1504, Basel succeeded in selling the Three Brothers to Augsburg banker Jakob Fugger after a year of negotiations.[9]:54[12] A merchant by trade, Fugger had become one of the wealthiest individuals in history by dealing in textiles and metals, and through extending loans to the Habsburg dynasty. The Basel sale included the Brothers and three other pieces of jewellery from Charles' hoard—the Federlin (little feather), the Gürtelin (little garter) and the White Rose—for a total price of 40,200 florins;[12] enough to pay 3,300 common laborers for a year.[9]:79 While this constituted a significant expense, Fugger made many such transactions over the years, and the price pales in comparison to his total assets, which reached more than 2 million guilders at his death in 1525.[13] For Fugger, jewellery and precious stones were a highly fungible capital reserve,[9]:47–74 and an investment to be sold at a profit to the right client.[12] In fact, Fugger had already had Emperor Maximilian I in mind as a buyer when he purchased the jewels, but the latter balked at the exorbitant asking price and bought everything but the Brothers.[14]

The pendant stayed with the Fuggers for almost 50 years, until Jakob's nephew Anton Fugger—who was now running the family business—decided to liquidate part of the family possessions. He first unsuccessfully offered the Brothers to King Ferdinand I and Emperor Charles V, while a bid from the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent was refused because Anton did not want the jewel to fall into non-Christian hands.[12] When Johann Jakob Fugger commissioned a history of the House of Habsburg in 1555, the Three Brothers still received explicit mention as a "treasure known to all Christendom" that the Fuggers had owned.[11]

While the details of the transaction are obscure, the negotiations between the Fuggers and the English Crown about purchasing the Brothers likely began under King Henry VIII.[14] As a renaissance monarch, Henry was expected to appear magnificent[15] – as John Fortescue argued in his hugely influential 15th-century treatise The Governance of England, a king needed "riche clothes, riche furres [and] rich stones [...] as bi sitith is roiall mageste".[16] As early as 1544, a letter from the Fugger office in Antwerp mentioned the imminent departure of an employee with jewels to be sold to Henry.[1] However, negotiations dragged on until Henry died in 1547, and were only concluded in May 1551 by his successor, the then-14 year old Edward VI. In his diary, the King wrote that he in fact had to buy the jewel from "Anthony Fulker" (Anton Fugger) for the princely sum of 100,000 crowns because the monarchy owed the Fugger's bank £60,000.[17] The transaction was recorded in an update to the Inventory of Henry VIII of England,[18] after which the Brothers became part of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom.

As an English crown jewel

Edward handed over the pendant to his Lord High Treasurer William Paulet for safekeeping on 7 June 1551,[19] and in 1553 it was decided to gift the Brothers to Edward's half-sister Mary on the occasion of her wedding to Prince Philip of Spain in 1554. The jewel is described in a list of items delivered to Mary on 20 September 1553 as "a great pendounte bought of the ffowlkers in fflaunders havinge three lardge ballaces set without foyle, one lardge pointed diamounte and iiij lardge perles, whereof one is pendaunte",[1] which indicates that it had seen very few, if any, alterations since John the Fearless had first taken possession of it more than 150 years earlier. King Edward died before Mary's marriage, who in turn took the throne under controversial circumstances, only to die just five years later after a short and tumultuous reign.

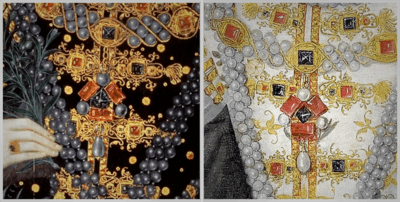

Seemingly never straying far from the current monarch, the Three Brothers made a grand re-appearance during the reign of Mary's successor, the 'virgin queen' Elizabeth I. Much like her father Henry VIII, Elizabeth knew when and how to use ostentatious displays of wealth[20] and evidently liked the showy red-and-white piece of jewellery with the unusual triangular arrangement.[21] The Queen wore it as part of her crown jewels prominently on several occasions,[22] and it is clearly visible in at least two portraits of her. First, in the famous "Ermine Portrait" (c.1585) attributed to William Segar, in which the Brothers appear suspended from a massive, pearl-studded carcanet or necklace, dramatically offset against a black dress.[21][23] The painting can today be seen in the collection at Hatfield House. And second, on the less well-known "Elizabeth I of England holding an olive branch" (c. 1587) by an unknown painter, originally given to the Navarrese diplomat François de Civille, where the pendant takes pride of place as the only significant piece of jewellery worn against a richly decorated white dress. The jewel was so tied to Elizabeth's public image that a representation of the Brothers in marble and gold was made part of her tomb effigy in the Henry VII Chapel in Westminster Abbey; the element was lost for over a century until its restoration in 1975.[24]

When Elizabeth died in 1603 at the end of a 45-year reign, the jewel passed to her successor, James I. In 1606 the Three Brothers were listed in an inventory of the crown jewels amongst those pieces "never to be alienated from the Crown".[1][25] The pendant was a favourite of James, who re-fashioned it into a hat jewel.[26] A portrait of James produced around 1605 shows the Brothers in great detail as the king wears it as part of a pearl-studded band on a stylish black hat.[1] He wore other crown jewels in a similar fashion, such as the Mirror of Great Britain.

Towards the end of James' reign, the jewel was reset, possibly even for the first time since its creation. In 1623, James' son and heir apparent Charles was sent on an incognito mission to Spain to negotiate a marriage between himself and the Infanta Maria Anna of Spain in a diplomatic maneuver known as the Spanish match. Opulent jewellery was to be brought on the trip in an attempt to dazzle Philip III of Spain and convince him of giving up his daughter's hand in marriage.[1] Crown jeweller George Heriot[27] worked four days and nights non-stop to reset the chosen pieces of jewellery, with a report on 17 March stating that he had taken "the great pointed diamond [...] out of the jewell called the Brethren, which he commandeth to be the most compleat stone that ever he sawe" and which he valued at £7,000.[28] James wrote Charles on the same day that he would "send you for youre wearing the Three Brethren that you knowe full well, but newlie sette".[29]

Later history and loss

When the Spanish match failed to materialise and James died in March 1625, the newly crowned Charles I instead married French princess Henrietta Maria. Charles continuously quarrelled with the Parliament of England over governmental policy, religion, and the raising of revenue for the crown.[30] As believers in the divine right of kings, Charles and Henrietta were convinced that the crown jewels were their personal possessions.[31] Charles was plagued by financial problems and had already pawned the Brothers away in the Netherlands in 1626, redeeming them only in 1639.[32] When the monarchy faced bankruptcy in mid-1640, Charles sent Henrietta to the continent to sell off what she could of the crown jewels.[33] The Queen arrived in The Hague on 11 March 1642 despite the protestations of Parliament that she had taken with her "Treasure, in Jewels, Plate, and ready Money" that was likely to "impoverish the State" and be used to forment unrest in England.[34] However, Henrietta found that potential buyers were hesitant to touch important pieces such as the Three Brothers, writing to her husband: "The money is not ready, for on your jewels, they will lend nothing. I am forced to pledge all my little ones".[35] By June, Sir Walter Erle reported to Parliament that the Brothers were still unsold.[36][37]

It is at the end of Henrietta's trip in 1643 that the trail of the jewel begins to disappear. There is no record of her selling or pawning the pendant in the Netherlands, and Humphrey (2012) posits that the Brothers returned with her to England.[37] As the country descended into the First English Civil War between Charles and Parliament, Henrietta fled to Paris in 1644, where she again immediately attempted to raise funds.[38] Once more the local market showed little interest, but in early 1645, she succeeded in selling an unnamed piece of jewellery for the comparatively low price of 104,000 guilders. The piece was described as a "pyramidal diamond, 3 balas rubies, 4 pearls with the addition of a table cut diamond of 30 carats and two pointed diamonds", which closely matches the original description of the Three Brothers, which might have been altered by adding smaller diamonds – however, there is no definite proof that this was the same item.[34] A contemporary letter to Henrietta's secretary identifies two Hague jewellers and gemstone dealers, Thomas Cletcher jr. and Joachim de Wicquefort, as possible middlemen or buyers of the unnamed jewel. Cletcher had already been involved in the pawning of the Mirror of Great Britain in 1625 and would therefore have been familiar with Henrietta and the crown jewels.[34]

The ultimate fate of the Brothers after 1645 is unknown. It has been suggested that the jewel was broken up, bought by French chief minister Cardinal Mazarin,[2] or sold to an anonymous buyer through a bank in Rotterdam.[32] Long-standing speculation points to the possibility that the pendant was modified to create a jewel called the Three Sisters, which was offered to Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange around the time of Henrietta's sale in 1645. However, besides the possibly coincidental similarity in naming, there is no hard evidence to suggest that the Brothers became the Sisters.[34] There has been no confirmed sighting of the jewel since.[1]

In popular culture

British author Tobias Hill published the novel The Love of Stones in 2001, which charts the lives of several real and fictional persons coming in contact with the Three Brothers.[39]

See also

- Mirror of Great Britain, lost hat jewel also worn by James VI and I

- Florentine Diamond, another lost jewel supposedly once belonging to Charles the Bold

- List of missing treasures

References

- Strong, Roy (1966). "Three Royal Jewels: The Three Brothers, the Mirror of Great Britain and the Feather". The Burlington Magazine. 108 (760): 350–353. ISSN 0007-6287.

- SusanGems. "The Three Brethren, the Burgundian Crown Jewel". Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- Weldons (2014-10-31). "The Three Brethren Jewel -". Weldons of Dublin. Retrieved 2020-08-06.

- Ogden, Jack. Diamonds: An Early History of the King of Gems. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-300-23551-7. OCLC 1030892978.

- Deuchler, Florens (1963). Die Burgunderbeute; Inventar der Beutestücke aus den Schlachten von Grandson, Murten und Nancy, 1476/1477 (in German). Bern: Stämpfli. p. 123.

- Kovács, Éva, 1932- (2004). L'âge d'or de l'orfèvrerie parisienne au temps des princes de Valois (in French). Dijon: Faton. p. 388. ISBN 2-87844-063-3.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Vaughan, Richard, 1927-2014. (1962). "Burgundy, England and France: 1419-1435". Philip the Bold: the formation of the Burgundian state. Harvard University Press. OCLC 405255.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Winkler, Albert (2010-02-01). "The Battle of Murten: The Invasion of Charles the Bold and the Survival of the Swiss States". Faculty Publications: 19.

- Steinmetz, Greg. The richest man who ever lived: the life and times of Jacob Fugger. ISBN 978-1-4516-8856-6. OCLC 965139738.

- Ronald, Susan (2004). The Sancy Blood Diamond: Power, Greed, and the Cursed History of One of the World's Most Coveted Gems. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 36–38. ISBN 978-0-471-43651-5. OCLC 942897524.

- "Miniatur des Anhängers Die drei Brüder". www.hmb.ch (in German). Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- Siebenhüner, Kim (2012-01-01). "Where Did the Jewels of the German Imperial Princes Come From? Aspects of Material Cultural in the Empire". The Holy Roman Empire, 1495-1806: A European Perspective: 333–348. doi:10.1163/9789004228726_019.

- "Anton Fugger". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Lieb, Norbert (1952). Die Fugger und die Kunst (in German). München: Schnell & Steiner. pp. 84, 138. OCLC 13964318.

- Hayward, Maria. "Treasured possessions: The material world of Henry VIII" (PDF).

- Fortescue, John, Sir, 1394?-1476? (1885). Charles Plummer (ed.). The governance of England: otherwise called the difference between an absolute and a limited monarchy (PDF). Oxford University Press. p. 125.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Jordan, W. K. (1966). Edward VI The Chronicle and political papers of King Edward VI. p. 60. OCLC 468585928.

- Ward, Philip, 1938- Starkey, David, 1945- (1998). The Inventory of King Henry VIII : Society of Antiquaries MS 129 and British Library MS Harley 1419. 1. ISBN 1-872501-89-3. OCLC 42834727.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Ward, Philip, 1938- Starkey, David, 1945- (1998). The Inventory of King Henry VIII, Vol. 1. ISBN 1-872501-89-3. OCLC 42834727.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Elizabeth I's Royal Wardrobe". Royal Museums Greenwich. 2015-08-17. Retrieved 2020-08-06.

- Scarisbrick, Diana. "Jewellery of Queen Elizabeth I". Haughton International. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- Twining, Edward F. (1960). A history of the crown jewels of Europe. Batsford. OCLC 1070831637.

- Strong, Roy C. (1963). Gloriana: The Portraits of Queen Elizabeth I. Oxford University Press. p. 82. ISBN 0-7126-0944-X. OCLC 768835625.

- "Elizabeth I". Westminster Abbey. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- Nichols, John (1828). The Progresses, Processions and Magnificent Festivities of King James the First, His Royal Consort, Family and Court, Etc. London. p. 46.

- Nash, Michael L. (2017), Nash, Michael L. (ed.), "The Jewels of the Kingdom", Royal Wills in Britain from 1509 to 2008, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 61–85, doi:10.1057/978-1-137-60145-2_5, ISBN 978-1-137-60145-2, retrieved 2020-08-13

- "Heriot, George (1563–1624), jeweller and philanthropist". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13078. Retrieved 2020-08-13.

- "British History Online: James 1 - volume 139: March 1-18 1623". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- Nichols, John (1828). The Progresses, Processions and Magnificent Festivities of King James the First, His Royal Consort, Family and Court, Etc. London. p. 833.

- Sharpe, Kevin (1992). The personal rule of Charles I. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05688-5. OCLC 25832187.

- Burgess, Glenn (1992). "The Divine Right of Kings Reconsidered". The English Historical Review. 107 (425): 837–861. ISSN 0013-8266.

- "Three Brothers Jewel. Mystic history of stolen royal jewelry". Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- David Sargeant, Jack (2020). "Parliament and the Crown Jewels in the English Revolution, 1641–1644". The Historical Journal. 63 (4): 811–835. doi:10.1017/S0018246X19000438. ISSN 0018-246X.

- Humphrey, David (2014-07-15). "To Sell England's Jewels: Queen Henrietta Maria's visits to the Continent, 1642 and 1644". E-rea. Revue électronique d’études sur le monde anglophone (11.2). ISSN 1638-1718.

- Harleian MS 7379: 2

- "House of Commons Journal Volume 2: 11 June 1642 | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- Humphrey, David (2012). "A Chronicle of the 'Three Brothers' Jewel between 1623 and c.1644". Jewellery Studies. 12.

- Britland, Karen (2011), Mansel, Philip; Riotte, Torsten (eds.), "Exile or Homecoming? Henrietta Maria in France, 1644–69", Monarchy and Exile: The Politics of Legitimacy from Marie de Médicis to Wilhelm II, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 120–143, doi:10.1057/9780230321793_7, ISBN 978-0-230-32179-3, retrieved 2020-08-12

- Murphy, Bernadette (2002-01-29). "In Search of the Three Brethren, Jewels Valued Beyond Price". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2020-08-06.