The Romaunt of the Rose

The Romaunt of the Rose (the Romaunt) is a partial translation into Middle English of the French allegorical poem, le Roman de la Rose (le Roman). Originally believed to be the work of Chaucer, the Romaunt inspired controversy among 19th-century scholars when parts of the text were found to differ in style from Chaucer's other works. Also the text was found to contain three distinct fragments of translation.[1] Together, the fragments—A, B, and C—provide a translation of approximately one-third of Le Roman.

There is little doubt that Chaucer did translate Le Roman de la Rose under the title The Romaunt of the Rose: in The Legend of Good Women, the narrator, Chaucer, states as much. The question is whether the surviving text is the same one that Chaucer wrote. The authorship question has been a topic of research and controversy. As such, scholarly discussion of the Romaunt has tended toward linguistic rather than literary analysis.[2]

Scholars today generally agree that only fragment A is attributable to Chaucer, although fragment C closely resembles Chaucer's style in language and manner. Fragment C differs mainly in the way that rhymes are constructed.[3] And where fragments A and C adhere to a London dialect of the 1370s, Fragment B contains forms characteristic of a northern dialect.[1]

Source and early texts

Le Roman de la Rose

Guillaume de Lorris completed the first 4,058 lines of le Roman de la Rose circa 1230. Written in Old French, in octosyllabic, iambic tetrameter couplets, the poem was an allegory of what D. S. Brewer called fine amour.[4] About 40 years later, Jean de Meun continued the poem with 17,724 additional lines. In contrasting the two poets, C. S. Lewis noted that Lorris' allegory focused on aspects of love and supplied a subjective element to the literature, but Meun's work was less allegory and more satire. Lewis believed that Meun provided little more than a lengthy series of digressions.[5]

The Romaunt of the Rose

Geoffrey Chaucer began translating Le Roman into Middle English early in his career, perhaps in the 1360s.[6] Chaucer may have selected this particular work because it was highly popular both among Parisians and among French-speaking nobles in England.[7] He might have intended to introduce the poem to an English audience as a way of revising or extending written English.[8] Moreover, Le Roman was controversial in its treatment of women and sex, especially in the verses written by Meun.[9] Chaucer may even have believed that English literature would benefit from this variety of literature.[10]

Chaucer's experience in translating Le Roman helped to define much of his later work. It is a translation which shows his understanding of French language. Russell Peck noted that Chaucer not only drew upon the poem for subject matter, but that he trained himself in the poem's literary techniques and sensibilities. "Le Roman" enabled Chaucer to introduce a "stylish wit and literary manner" to his English audience and then to claim these attributes as his own.[11]

The Romaunt is written in octosyllabic, iambic tetrameter couplets in the same meter as le Roman.[12] The translation is one of near-minimal change from the original. Raymond Preston noted that "a better poem in English would have meant a lesser translation."[13]

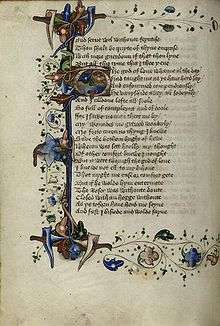

An early fifteenth-century manuscript of the Romaunt of the Rose was included in the library William Hunter donated to the University of Glasgow in 1807.

In 1532, William Thynne published the first collected edition of Chaucer's work. Commissioned by Henry VIII to search for copies of Chaucer's manuscripts in the libraries and monasteries of England, Thynne printed a collection that included the Romaunt of the Rose.[14]

Analyses

Henry Bradshaw and Bernard ten Brink

By 1870, Henry Bradshaw had applied his method of studying rhymes to Chaucer's poetry. Working independently, Bradshaw and Dutch philologist Bernard ten Brink concluded that the existing version of the Romaunt was not Chaucer's translation of le Roman, and they placed the work on a list that included other disqualified poems no longer considered to have been written by Chaucer.[15]

Walter Skeat

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Citing research by both Linder and Kaluza, Walter Skeat, a nineteenth-century scholar, divided the Romaunt into the following three fragments that correspond to French text in le Roman:

| Breaks in the Romaunt | Text in the Romaunt | Corresponding text in le Roman |

|---|---|---|

| Fragment A | lines 1–1,705 | lines 1–1,678 |

| Fragment B | lines 1,706–5,810 | lines 1,679–5,169 |

| Fragment C | lines 5,811–7,698 | lines 10,716–12,564 note: 5,547 untranslated lines occur between fragments B and C |

Le Roman continues another 9,510 lines without a corresponding English translation in the Romaunt. When the 5,547 untranslated lines between fragments B and C are included, the English translation is roughly one-third of the original French poem.

Skeat subjected the Romaunt text to a number of tests, and he found that on average, fragment A required 101.6 lines of English poetry for every 100 lines of French poetry. Fragment C required 102.1 English lines for 100 French lines. But Fragment B required 117.5 English lines for 100 French lines. Skeat also found that a northern dialect was present in fragment B, where Chaucer almost exclusively used a London dialect. Fragment B also broke with Chaucer's rule in rhyming words that end in y. Finally, Skeat discovered that where Chaucer did not employ assonant rhymes, fragment B depended upon them. These discoveries led nineteenth-century scholars to conclude that fragment B was not written by Chaucer.

Skeat found that Fragment C departs from Chaucer's usage, beginning again with words ending in y that the author rhymed with words ending in ye. Where Chaucer rhymed the words wors and curs in The Canterbury Tales, the author of fragment C rhymed hors and wors. In what Skeat said would be a "libellous" attribution to Chaucer, the author of fragment C rhymed paci-ence with venge-aunce and force with croce. Fragment C rhymes abstinaunce with penaunce and later abstinence with sentence. These and other differences between fragment C and the works of Chaucer led Skeat to disqualify fragment C.

Later studies

Further research in the 1890s determined that the existing version of the Romaunt was composed of three individual fragments—A, B, and C--and that they were translations of le Roman by three different translators.[1] The discussion about the authorship of the Romaunt of the Rose is by no means ended. In a recent metrical analysis of text, Xingzhong Li concluded that fragment C was in fact written by Chaucer or at least "88% Chaucerian."[3]

Synopsis

The story begins with an allegorical dream, in which the narrator receives advice from the god of love on gaining his lady's favor. Her love being symbolized by a rose, he is unable to get to the rose.

The second fragment is a satire on the mores of the time, with respect to courting, religious order, and religious hypocrisy. In the second fragment, the narrator is able to kiss the rose, but then the allegorical character Jealousy builds a fortress encircling it so that the narrator does not have access to it.

The third fragment of the translation takes up the poem 5,000 lines after the second fragment ends. At its beginning, the god of love is planning to attack the fortress of Jealousy with his barons. The rest of the fragment is a confession given by Fals-Semblant, or false-seeming, which is a treatise on the ways in which men are false to one another, especially the clergy to their parishioners. The third fragment ends with Fals-Semblant going to the fortress of Jealousy in the disguise of a religious pilgrim. He speaks with Wikked-Tunge that is holding one of the gates of the fortress and convinces him to repent his sins. The poem ends with Fals-Semblant absolving Wikked-Tunge of his sins.

See also

References

- Sutherland, Ronald (1967). The Romaunt of the Rose and Le Roman De La Rose. Oakland: University of California Press. pp. Introduction.

- Eckhardt, Caroline (1984). The Art of Translation in The Romaunt of the Rose. Studies in the Age of Chaucer. 6. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press. pp. 41–63. ISBN 978-0-933-78405-5.

- Li, Xingzhong (November 17, 2008). Studies in the History of the English Language--Metrical evidence: Did Chaucer translate The Romaunt of the Rose?. IV. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 155–179. ISBN 978-3110205879.

- Brewer, D. S. (1966). Chaucer and Chaucerians (1st ed.). Ontario: Thomas Nelson and Sons LTD. pp. 16–17.

- Dahlberg, Charles (1995). The Romaunt of the Rose. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 9780691044569.

- For a chronological perspective of events in Chaucer's life, see eChaucer at the University of Maine.

- Modern scholars consider Roman de la Rose to be "the most influential French poem of the Middle Ages." See Allen, Mark; Fisher, John H. (2012). The Complete Poetry and Prose of Geoffrey Chaucer (3 ed.). Boston: Michael Rosenberg. p. 720. ISBN 9780155060418.

- Chaucer intended English to "attain higher spheres of expression." see Sánchez-Martí, Jordi (2001). Chaucer's "Makyng" of the Romaunt of the Rose. Journal of English Studies. 3. Logroño: Universidad de la Rioja. pp. 217–236.

- The Riverside Chaucer (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. 2008. p. 686. ISBN 978-0199552092.

- The poem is "an exploration of human erotic psychology." See Allan and Fisher

- Peck, Russell A. (1988). Chaucer's Romaunt of the Rose and Boece, Treatise on the Astrolabe, Equatorie of the Planetis, Lost Works, and Chaucerian Apocryphia. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. Introduction.

- By retaining the original form, Chaucer "confirmed his fidelity to the original." see Sánchez-Martí.

- Preston is quoted in Eckhardt, p. 50.

- Spurgeon, Caroline F. E. (1925). Five Hundred Years of Chaucer Criticism and Allusion 1357--1900. I. London: Cambridge University Press. pp. cxvi.

- Prothero, George Walter (1888). A Memoir of Henry Bradshaw. London: Kegan Paul, Trench. pp. 352–353.

Further reading

- Rosalyn Rossignol, Critical Companion to Chaucer: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work (Infobase Publishing, 2006)

- Christopher Canon, The Making of Chaucer's English: A Study of Words (Cambridge University Press, 1998)

External links

- Fragment A at Bartleby

- Pickering edition, 1845 at Google Books

- Skeat's analysis of the text at Project Gutenberg

- Hunterian Museum. The manuscript collection at the University of Glasgow, including the pre-typographic copy of the Romaunt of the Rose.

.jpg)