The Green Room (film)

The Green Room (French: La Chambre verte) is a 1978 French film directed by François Truffaut and based on the Henry James short story, "The Altar of the Dead", in which a man becomes obsessed with the dead people in his life and builds a memorial to them. It is also based on two other short stories by Henry James: "The Beast in the Jungle" and "The Way It Came". It was Truffaut's seventeenth feature film as a director and the third and last of his own films in which he acted in a leading role. It starred Truffaut, Nathalie Baye, Jean Dasté and Patrick Maléon.

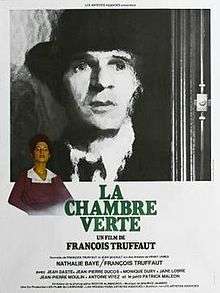

| The Green Room | |

|---|---|

Film poster | |

| Directed by | François Truffaut |

| Produced by | Marcel Berbert François Truffaut |

| Written by | Jean Gruault François Truffaut |

| Based on | "The Altar of the Dead", "The Beast in the Jungle" and "The Way It Came" by Henry James |

| Starring | François Truffaut Nathalie Baye Jean Dasté |

| Music by | Maurice Jaubert |

| Cinematography | Néstor Almendros |

| Edited by | Martine Barraqué-Curie |

Production company | Les Films du Carrosse |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 94 minutes |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Budget | ₣3 million |

| Box office | 161,293 admissions (France)[1] |

Truffaut spent several years working on the film's script and felt a special connection to the theme of honouring and remembering the dead. In the film, he included portraits of people from his own life at the main character's "Altar of the Dead". The Green Room was one of Truffaut's most praised films, and also one of his least successful financially.

Plot

The action takes place ten years after the end of World War I in a small town in France. The protagonist, Julien Davenne, is a war veteran who works as an editor at the newspaper, The Globe. He specializes in funeral announcements ("a virtuoso of the obituary", as defined by its editor-in-chief) and the thought of death haunts him. Davenne has reserved a room for the worship of his wife, Julie, on the upper floor of the house he shares with his elderly housekeeper, Mrs. Rambaud, and Georges, a deaf-mute boy. His wife had died eleven years prior, at the height of her beauty.

During a thunderstorm, a fire destroys the green room, Davenne managing to save only pictures and portraits of his wife. On discovering an abandoned chapel in ruins, at the same cemetery where Julie is buried, Julien decides to consecrate it not only to his wife but to all the cemetery's dead, having reached "that point in life where you know more dead than alive." The place is transformed into a forest of lighted candles, with photos of all the people he treasured in life.

To keep the chapel, Davenne calls a young woman, Cécilia, secretary of the auction house that has regained a ring that had belonged to Julie. The friendship between the two seems to evolve when Paul Massigny, a French politician and Davenne's former best friend, dies. The film suggests that Massigny once betrayed Davenne but does not say what constituted the betrayal. When Davenne first visits Cécilia at home, Davenne discovers that the living room is full of pictures of Massigny and, without asking for explanations, leaves.

At the chapel, Cecilia tells him that she was one of Massigny's many women and still loves him. She requests that Massigny be represented by one of the candles on the altar. After being rebuffed by Davenne, Cecilia breaks off the relationship and he breaks down. He locks himself away at home, refusing to eat, to see the doctor, or talk. The managing editor of The Globe recommends that Cécilia write him a letter. She finally declares her love, knowing he would never reciprocate, "because to be loved by you, I should be dead." Having forgiven Massigny, Davenne joins her in the chapel, but he is weakened, falls to the ground and dies. Cécilia completes the work, as she had asked the first time, dedicating one last candle to Julien Davenne.

Cast

- François Truffaut as Julien Davenne

- Nathalie Baye as Cécilia Mandel

- Jean Dasté as Bernard Humbert, editor of The Globe

- Jean-Pierre Ducos as the Priest in the mortuary room

- Monique Dury as Monique, secretary at The Globe

- Jeanne Lobre as Mme Rambaud (as Jane Lobre)

- Jean-Pierre Moulin as Gérard Mazet

- Antoine Vitez as the Bishop's secretary

- Patrick Maléon as Georges

- Laurence Ragon as Julie Davenne

- Marcel Berbert as Dr. Jardine

- Christian Lentretien as the Speaker at the cemetery

- Annie Miller as Genevieve Mazet, the first Mme Mazet

- Marie Jaoul as Yvonne Mazet, the second Mme Mazet

- Guy D'Ablon as the Wax Dummy maker

- Anna Paniez as the little girl playing the piano

- Alphonse Simon as the one-legged man

- Henri Bienvenu as Gustave, the auctioneer

- Thi-Loan Nguyen as the Apprentice Artisan (as Thi-Loan N'Guyen)

- Serge Rousseau as Paul Massigny

- Jean-Claude Gasché as a Police Officer

- Martine Barraqué as a nurse at saleroom

- Josiane Couëdel as a nurse at the cemetery

- Jean-Pierre Kohut-Svelko as the disabled man at saleroom

- Roland Thénot as the disabled man at cemetery

- Nathan Miller as Genevieve Mazet's son

- Carmen Sardá-Cánovas as the woman with the rosary

- Gérard Bougeant as the cemetery's keeper

Production

Background and writing

Truffaut first began work on The Green Room in December 1970 after reading the works of Henry James. Truffaut especially liked "The Altar of the Dead" and asked his friend Aimée Alexandre to translate a new French version for him. Alexandre also recommended works by Anton Chekov and Leo Tolstoy with similar themes, while Truffaut did his own research on James's life and visited his home in Boston. Truffaut worked on other projects until 1974, when a new French version of the short story was published, renewing his interest. Truffaut commented on the film, "the story was difficult to construct, but at the same time, I was attracted to the subject."[3] In July of that year he then reached a contract agreement with screenwriter Jean Gruault to begin drafting a film adaptation.[4] Truffaut and Gruault had previously collaborated on Jules and Jim (1962), The Wild Child (1970), and Two English Girls (1971). [5]

For several years Truffaut had become increasingly interested in people from his life who had died, beginning with his mentor and father-figure André Bazin, who had died the day before Truffaut began shooting his first feature, The 400 Blows. Truffaut told a reporter for L'Express: "I'm faithful to the dead, I live with them. I'm forty-five and already beginning to be surrounded by dead people."[4] [6]In 1977 Truffaut lost two other important father-figures: Cinémathèque Française director Henri Langlois and Roberto Rossellini, whom Truffaut called "the most intelligent man, with André Bazin" during an interview with Le Matin de Paris.[4][7] Around this time Truffaut had watched Shoot the Piano Player and noticed that half the actors had since died. In an interview with L'Humanité-Dimanche magazine Truffaut asked "Why not have the same range of feelings for the dead as for the living, the same aggressive or affectionate relationship?" and added that he wanted to film "what it would be like to show on screen a man who refuses to forget the dead."[8] [9] According to him, The Green Room is not the worshipping of death, but an extension of the love for the people that we have met and who are no longer alive, and the idea that they have a permanency. What matters is that Davenne refuses to forget, and this refusal is important for Truffaut.[10]

Truffaut recommended that Gruault read James's "The Beast in the Jungle" and "The Way It Came", which were also incorporated into the film. Truffaut also wanted to change the setting of the original story to 1920s France with World War I as a major factor in the plot. In fact, he stated that he chose to adapt Henry James’ 1928 themes because he wanted to link them directly with the memory of the First World War. The idea of massacre, millions of deaths, is not evoked as effectively by the Second World War.[11] By spring 1975 Gruault had finished a first draft called La Fiancée disparue (The Vanished Fiancée).[12] Truffaut thought the script was too long and Gruault made cuts. Truffaut's continuing requests for script modifications caused Gruault to become dissatisfied working with him. Truffaut, also busy writing the script for Alain Resnais's Mon oncle d'Amérique,[13] put the entire project on hold and eventually shot Small Change and The Man Who Loved Women. He continued to research the themes of The Green Room, reread Marcel Proust's Remembrance of Things Past and Japanese literature such as the works of Jun'ichirō Tanizaki. He also asked Éric Rohmer for help with the script, but the material thus far produced did not interest the director.[13]

In October 1976, Truffaut showed a new draft to Gruault, which now included a deaf-mute child as the main character Julien Davenne's protégé, and had Davenne work as an obituary writer in a small Parisian magazine. The presence of Paul Massigny was also vital for the development of the story. Indeed, Truffaut stated that without Massigny there would be no film because it would be too static, and that The Green Room is a tale in which Massigny is the anti-hero.[14] Gruault finished a new version of the script by February 1977. Truffaut worked on it with his assistant Suzanne Schiffman and completed the final draft in May 1977.[15]

Casting

For the lead role of Julien Davenne, Truffaut first wanted to cast actor Charles Denner, but he was not available. Because of the personal nature of the film and the character of Julien Davenne, Truffaut decided to play the part, stating that "this film is like a handwritten letter. If you write by hand, it isn’t perfect, the writing may be shaky, but it is you, your writing." [16] . This decision was not simply taken because Truffaut embodied the character, but because Davenne’s obsession, what he does throughout the whole film, what defines him, that is, keeping the memory of the dead alive, refusing to forget them, linked in a way to the activity of the director.[17] Specifically, he felt a closeness to the character of Davenne, due to his own valuations of remembrance of the dead as helping in the "struggle against the transience of life".[18] Despite his strong feeling for the character, Truffaut was hesitant about the role and thought he may be perceived as too old. He had a wig made, but ended up not using it.[15]. It was Truffaut's third and last of his own film in which he played a leading role.[19] According to co-star Nathalie Baye, Truffaut almost shut the film down for fear of a bad performance: "He would say to me, 'It's madness; it will never work!' And he came close to wanting to stop everything."[15]

Baye was cast as Cécilia after having worked with her in Day for Night and The Man Who Loved Women. Baye later stated that "If Francois asked me to perform with him, it was because he knew I wasn't the kind of actress who caused problems. He could rely on me, which was very reassuring to him."[15] Truffaut filled out the cast with Jean Dasté as Davenne's boss at The Globe, Antoine Vitez as a clergyman, Jean-Pierre Moulin as a widower that Davenne comforts in the film and Patrick Maléon as the deaf-mute child. Truffaut also cast technicians and personnel from his production company in small roles.[20]

When asked about the message of The Green Room, Truffaut said "I am for the woman and against the man. As this century approaches its end, people are becoming more stupid and suicidal, and we must fight against this. The Green Room is not a fable, not a psychological picture. The moral is: One must deal with the living! This man has neglected life. Here we have a breakdown of the idea of survival."[21]

Filming

The Green Room was shot in the fall of 1977 in Honfleur, France with a budget of 3 million francs provided by United Artists. That summer, Truffaut scouted locations and hired his longtime collaborator, Néstor Almendros, as cinematographer. To give the film a Gothic look, Almendros used candle light as both source and practical lighting, with electrical lights used to "exploit the contrast between electric light and a flood of candlelight to give the film a ghostly quality." [22] Truffaut also intended a resulting lack of colour throughout filming, condemning colour as a removal of the final "barrier" between film and reality: "If there is nothing false in a film, then it is not a film." [23] Almendros later said that, despite the film's somber tone, "this film was put together with joy, and the shooting was the most pleasant" of his career.[24] Many of the scenes were shot in the four-story Maison Troublet in Honfleur. This house and its grounds included sets for many of the film's main locations: Davenne's house, his office at The Globe and the auction room.[22][25]

Other locations included the Caen cemetery and the Carbec Chapel in Saint-Pierre-du-Val. The chapel was used for Davenne's shrine to the dead, with Jean-Pierre Kohut-Svelko designing the set inside.[22] Among the portraits included in the shrine are Henry James, Oscar Wilde, an old man who played a small role in Truffaut's Two English Girls, actor Oskar Werner in a World War I uniform,[26] Jacques Audiberti, Jean Cocteau, Maurice Jaubert, Raymond Queneau, Jeanne Moreau and her sister Michelle Moreau, Louise Lévêque de Vilmorin, Aimée Alexandre, Oscar Lewenstein, Marcel Proust, Guillaume Apollinaire and Sergei Prokofiev, many of whom were idolised figures of Truffaut's .[27]

Filming began on October 11, 1977 and lasted until November 27, 1977. The atmosphere on the set was especially fun and Nathalie Baye revealed that she and Truffaut often had laughing fits during takes. However, she also admits to having found it difficult to receive comprehensive direction from Truffaut, as he remained highly focused on his own performance. Baye also had difficulty performing alongside Truffuat, due to his "expressionless, nearly mechanical" approach to acting, which required her to adjust her own approaches accordingly. [28]

Themes

Since the semi-autobiographical The 400 Blows (1959), it has been noted that Truffaut often portrayed personal experiences and emotions throughout his films. Via such expressionistic use of the medium, he proclaimed himself as a film auteur, within a theory of film as art which he personally advocated as a director and a critic. As a result, Truffaut's films often appeared to focus on certain themes and stylisations, such as the vitality of youth and childhood, particularly embodied by the character of Antoine Doinel, who is a recurring presence across a number of his films. The Green Room however was made towards the end of Truffaut's career, and thematically the film contrasts to his earlier works. The Green Room appears to reminisce on childhood, whilst focusing more on the final stages of life, as Truffaut expresses his views of death and remembrance of the dead. This theme for a film had "preoccupied him for several years and had been accentuated by the deaths of numerous friends and colleagues",[29] such as those who previously worked alongside him on Shoot the Piano Player. Nonetheless, the alternative theme of the film again reflects Truffaut's sense of personal expressionism throughout his career. When asked "what do you make of the contradiction between the cult of death and the love of the life?" Truffaut replied "it's the theme of the film."[3] Gillain wrote that the film "points to cinema as a celebration of memory."[30] Yet, also thematic throughout The Green Room is a familiar "estrangement from human contact and romantic obsession", which has been prominent in "most of the films that Truffaut has made over a period of twenty years." [31]

Music

Truffaut chose pre-recorded music from composer Maurice Jaubert's 1936 "Concert Flamand", with whom he had already collaborated four times,[32] and played it on set in order to create a rhythm[33] and establish a religious, ritualistic atmosphere for the cast and crew. As Truffaut has stated, both camera and actors movements follow Jaubert's music rhythm.[10] Filmmaker François Porcile later said "It's not surprising to find, in the sudden explosive tension and somber conviction of his acting, a direct echo of Jaubert's style, with its gathering momentum and sudden restraint, its reticence and violence."[33] Truffaut explained: "I realized that his music, full of clarity and sunlight, was the best to accompany the memory of all these dead."[33] However, an infrequent use of music throughout the final film sees a consistent quietness take place, which is regarded to have masked "an exploration of human isolation in an inhuman society and of the strength and limitations of moral and aesthetic purity." [31] Gillain wrote that the film is cut like a musical composition and that each scene "performs a suite of variations on a single theme."[34]

Release and reception

Truffaut completed the editing of The Green Room in March 1978 and showed it to his trusted friends and co-workers, who immediately praised the film and called it one of his best films. Many wrote to him via letter, such as Isabelle Adjani who revealed that "Of all your films it is the one that most moved me and spoke to me, along with Two English Girls. I felt good crying in your presence."[35] Alain Delon told Truffaut that "The Green Room, along with Clément, Visconti and very few others, is part of my secret garden."[35] Éric Rohmer told him that "I found your film deeply moving. I found you deeply moving in your film."[35] Antoine Vitez told Truffaut "I haven't yet told you the emotion I felt on seeing The Green Room. What I see in it, deep down, is kindness, and that's what touches me most. Thank you for having included me in it."[35]

Publicly, The Green Room was Truffaut's biggest financial failure but one of his most critically praised films. One major French film critic, François Chalais of Le Figaro, disliked the film, but Truffaut received high praise elsewhere.[35] Pascal Bonitzer viewed the film as "most profound, and without much exaggeration, one of the most beautiful French films of recent years,"[36] and that "it is not for nothing that Truffaut embodies his character, and that in the latter, Julien Davenne, the author and the actor are entwined in the tightest possible way...rarely does a filmmaker involve himself to that point - involving his body (and note all the ambiguity of the word in the context of this funeral film) and even his dead; mixing together Julien Davenne's dead with those of François Truffaut in the flaming chapel where the film comes to an end."[36] Joel Magny called Julien Davenne the ultimate "truffaldian" hero, "unable to live the present moment in the fullness of his being, where he is...in a perpetual time-lag with reality."[37] The French magazine Télérama called Davenne "l'homme qui aimait les flammes" ("the man who loves the flames").[38] Jean-Louis Bory of Le Nouvel Observateur said that "In its simple and pure line, it resembles a cinematic testament. There will be other Truffaut films, but none that will ever be more intimate, more personal, more wrenching than this Green Room, altar of the dead."[35][39]

The Green Room was released on April 5, 1978 and was a financial failure, selling slightly more than 30,000 tickets[40] ( it has sold 161,293 admissions total as of 2015[1]) Truffaut knew that a film about death would be difficult to market or attract an audience, but felt strongly that "this kind of theme can touch a deep chord in many people. Everyone has their dead."[35][6] He hoped that the film would connect with the audience,[41] and stated that he wanted people to watch it with their jaws dropped, moving from one astonishing moment to the next.[34]

Truffaut took a personal interest in promoting the film and hired renowned press agent, Simon Misrahi, in his determination to make the film reach a larger audience, despite its subject matter.[35] A few days before the film's premiere, Truffaut completely changed his approach, putting more emphasis on his own track record as a filmmaker and the presence of rising star, Nathalie Baye. In a television appearance to promote the film, Truffaut showed two clips from the film that had nothing to do with the dead. Truffaut was extremely upset by the film's financial failure and referred to it as "The Empty Room". He publicly stated that he would not act again for at least ten years and admitted to Paris Match that he regretted not casting Charles Denner in the lead role.[42][43] Truffaut later blamed United Artists for not promoting the film properly, which led to his breaking from the US company for the first time in over ten years. His next film to make independently of American influence would be L'amour en fuite/Love on the Run.[44]

Truffaut premiered The Green Room in the US at the 1978 New York Film Festival where its reception was again ill-fated.[42] Vincent Canby of The New York Times gave the film a mixed review and criticized Truffaut's performance, saying that "Truffaut does not make it easy for us to respond to Davenne". Canby goes on to call the film " a most demanding, original work and one must meet it on its own terms, without expectations of casual pleasures."[45] Dave Kehr of the Chicago Reader said that the film "dead-ends in sheer neurosis" while praising the cinematography.[46] A negative review from Time Out blamed the film's "failure" on "Truffaut's lack of range as an actor [which] is not helped by the script's purple prose."[47] Truffaut himself eventually reflected on the reception of The Green Room as a case where he was able to "get out of trouble", rather than simply assert "I succeeded", in relation to the commercial failure but general critical success of the film.[48]

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a rating of 38%, based on 8 reviews, earning an average rating of 5.5 out of 10.[49] On the Internet Movie Database, The Green Room holds an average rating of 7.2 out of 10, based on 2,294 reviews.[50]

Awards and nominations

| Year | Award ceremony | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | César Awards | Best Cinematography | Néstor Almendros | Nominated |

References

- Box Office information for Francois Truffaut films at Box Office Story

- Allen 1985, p. 236-237.

- Bergan 2008, pp. 124.

- Baecque & Toubiana 1999, pp. 336.

- Marie & Neupert 2003, pp. 73-74.

- Unknown L'Express Article.

- Unknown Le Matin de Paris Article.

- Baecque & Toubiana 1999, pp. 337.

- Unknown L'Humanité-Dimanche Article.

- Truffaut & Gillain 1988, p. 372.

- Truffaut & Gillain 1988, p. 371.

- Insdorf 1978, pp. 232.

- Baecque & Toubiana 1999, pp. 338.

- Truffaut & Gillain 1988, p. 374.

- Baecque & Toubiana 1999, pp. 339.

- Bergan 2008, pp. 125.

- Mouren 1997, p. 128.

- Insdorf 1978, pp. 246.

- Insdorf 1978, pp. 220.

- Baecque & Toubiana 1999, pp. 339-340.

- Insdorf 1978, pp. 226.

- Baecque & Toubiana 1999, pp. 340.

- Bergan 2008, pp. 126.

- Wakeman 1988, pp. 1133.

- Gillain & Fox 2013, pp. 265-266.

- Insdorf 1978, pp. 224-226.

- Bloom 2000, pp. 316.

- Baecque & Toubiana 1999, pp. 340-341.

- Ingram & Duncan 2003, pp. 156.

- Gillain & Fox 2013, p. 277.

- Klein 1980, pp. 16.

- Insdorf 1989, p. 284.

- Insdorf 1978, pp. 224.

- Gillain & Fox 2013, p. 265.

- Baecque & Toubiana 1999, pp. 341.

- Wakeman 1988, pp. 1133-1134.

- Wakeman 1988, pp. 1134.

- Insdorf 1978, pp. 223.

- Unknown Le Nouvelle Observer Article.

- Baecque & Toubiana 1999, pp. 341-342.

- Ingram & Duncan 2004, p. 159.

- Baecque & Toubiana 1999, pp. 342.

- Unknown Paris Match Article.

- Baecque & Toubiana 1999, pp. 343–344.

- Canby, Vincent (September 14, 1979). "The Green Room (1978). Screen: Truffaut's 'The Green Room': High Priest of Death". The New York Times. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- Kehr 2014.

- "La Chambre Verte". Time Out. London. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- Bergan 2008, pp. 137.

- http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/green_room/

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0077315/

Bibliography

Articles

- Bloom, Michael E. (2000), 'Pygmalionesque Delusions and Illusions of Movement: Animation from Hoffmann to Truffaut', Comparative Literature, Vol. 52/4: 291-320.

- Kehr, Dave. "The Green Room". Chicago Reader.

- Klein, Michael (1980), 'Truffaut's Sanctuary: The Green Room', Film Quarterly, Vol 34/1: 15-20.

- Mouren, Yannick (1997) 'François Truffaut, l'Art du Récit', Etudes Cinématographiques Vol. 62: 128.

- Article Unknown, L'Aurore, April 3, 1978, cited in Baecque, Antoine de; Toubiana, Serge (1999), Francois Truffaut: a Biography. New York: Knopf.

- Article Unknown, L'Express, March 3, 1978, cited in Baecque, Antoine de; Toubiana, Serge (1999), Francois Truffaut: a Biography. New York: Knopf.

- Article Unknown, L'Humanité-Dimanche, June 5, 1977, cited in Baecque, Antoine de; Toubiana, Serge (1999), Francois Truffaut: a Biography. New York: Knopf.

- Article Unknown, Le Nouvelle Observateur, April 3, 1978, cited in Baecque, Antoine de; Toubiana, Serge (1999), Francois Truffaut: a Biography. New York: Knopf.

- Article Unknown, Paris Match, May 4, 1978, cited in Baecque, Antoine de; Toubiana, Serge (1999), Francois Truffaut: a Biography. New York: Knopf.

Books

- Allen, Don (1985). Finally Truffaut. London: Martin Secker & Warburg. ISBN 9780436011801.

- Baecque, Antoine de; Toubiana, Serge (1999). Truffaut: A Biography. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0375400896.

- Bergan, Ronald (2008). François Truffaut: Interviews. University of Mississippi Press: Jackson University Press. ISBN 978-1-934110-14-0.

- Gillain, Anne; Fox, Alistair (2013). François Truffaut: The Lost Secret. Bloomington, IL: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253008-39-8.*

- Ingram, Robert; Duncan, Paul (2003). François Truffaut: Film Author 1932-1984. London: Taschen GmbH. ISBN 3-8228-2260-4.

- Insdorf, Annette (1978). François Truffaut. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521478083.

- Marie, Michel; Richard, John (2003). The French new wave: an artistic school. Blackwell: Malden. ISBN 978-0631226581.

- Truffaut, François; Gillain, Anne (1988). Le Cinéma selon François Truffaut. Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 208-2114066.

- Wakeman, John (1987). World Film Directors, Volume 1. New York: The H. W. Wilson Company. ISBN 978-0824207571.