The Flowers of St. Francis

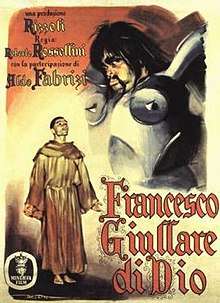

The Flowers of St. Francis (in Italian, Francesco, giullare di Dio, or "Francis, God's Jester") is a 1950 film directed by Roberto Rossellini and co-written by Federico Fellini. The film is based on two books, the 14th-century novel Fioretti Di San Francesco (Little Flowers of St. Francis) and La Vita di Frate Ginepro (The Life of Brother Juniper), both of which relate the life and work of St. Francis and the early Franciscans. I Fioretti is composed of 78 small chapters. The novel as a whole is less biographical and is instead more focused on relating tales of the life of St. Francis and his followers. The movie follows the same premise, though rather than relating all 78 chapters, it focuses instead on nine of them. Each chapter is composed in the style of a parable, and, like parables, contains a moral theme. Every new scene transitions with a chapter marker, a device that directly relates the film to the novel. When the movie initially debuted in America, where the novel was much less known, on October 6, 1952, the chapter markers were removed.[1]

| Francesco, giullare di Dio | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Roberto Rossellini |

| Produced by | Angelo Rizzoli |

| Written by | Roberto Rossellini Federico Fellini |

| Music by | Renzo Rossellini Enrico Buondonno |

| Cinematography | Otello Martelli |

| Edited by | Jolanda Benvenuti |

| Distributed by | Joseph Burstyn Inc. (US) |

Release date | 14 December 1950 |

Running time | 89 minutes |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian |

Included in the acting cast is Gianfranco Bellini as the narrator, who has voice-dubbed several American films for the Italian cinema.[1] Monks from the Nocere Inferiore Monastery played the roles of St. Francis and the friars.[1] Playing the role of St. Francis is a Franciscan brother who is not credited, Brother Nazario Gerardi.[1] The only professional actor in the film is the prominent Aldo Fabrizi, who had worked with Rossellini before, notably in the neorealistic film Rome, Open City.[1] The film garnered international acclaim for Fabrizi.[1] He began his film career scene in 1942, and is noted for both writing and directing his own vehicles. In this film, Fabrizi plays the role of Nicolaio, the tyrant of Viterbo.[1]

Rossellini had a strong interest in Christian values in the contemporary world.[2] Though he was not a practicing Catholic, Rossellini loved the Church's ethical teaching, and was enchanted by religious sentiment—things which were neglected in the materialistic world.[2] This interest helped to inspire the making of the film.[2] He also employed two priests to work on it with him, Félix A. Morlion O.P., and Antonio Lisandri O.F.M.[2] Though the priests contributed little to the script, their presence within the movie gave a feel of respectability in regards to theology.[2] Morlion vigorously defended Catholic foundations within Italian neorealism, and felt that Rossellini's work, and eventually scriptwriter Fellini's, best captured this foundation.[2]

Chapters

The movie begins with an introduction to the Franciscan friars as they trudge through the mud in the pouring rain to their hut. They find the hut occupied by a peasant and his donkey. The man, declaring the Franciscans thieves, drives them out of their hut. The Franciscans rejoice and see this as a call to follow Francis.

The rest of the film is divided into nine chapters each covering an incident in the life of St. Francis subsequent to his vocation. Each chapter is introduced by a parable and a chapter marker.

1 - How Brother Ginepro returned naked to St. Mary of the Angels, where the Brothers had finished building their hut.

While the Franciscan friars build a new hut, two brothers return with a set of prayer bells, a gift from a generous donor. As they celebrate, one Franciscan friar, Ginepro, steps out of the bushes in his underwear; he gave away his habit to a beggar. Francis gently admonishes Ginepro for his naive generosity.

2 - How Giovanni, known as “the Simpleton”, asked to follow Francis and began imitating him in word and gesture.

The Franciscans go to the woods to meet Francis, who instructs them to preach the Gospel by their example. Meanwhile, Brother Ginepro is ordered to stay behind and cook for the friars. While the brothers attend to their tasks, Francis prays "O! Signore, fa di me uno strumento della tua Pace," or in English, "Lord, make me an instrument of Thy peace."

After his prayer, an old man named Giovanni approaches Francis. He intends to give everything up to become a fellow Franciscan and has brought a bull with him as a gift. His family, however, reclaims the bull and leaves him to the Franciscans, who take Giovanni as a brother.

3 - Of the wonderful meeting between St. Clare and St. Francis at St. Mary of the Angels.

Clare has expressed an ardent desire to dine with Francis. He accepts, and the Franciscans make the preparations for the dinner. They decorate their hut with wildflowers and with the tools they have, they brush their hair and trim their beards.

A few moments later, Clare arrives with three of her sisters. Together, they and the friars enter the Chapel where Clare first professed her vows. They pray, and then they eat. The holiness of their conversation, as the narrator explains, ignites the sky with fire.

4 - How Brother Ginepro cut off a pig’s foot to give to a sick brother.

Ginepro and Brother Giovanni are tending to Brother Amarsebello, who has made himself sick from too much fasting. Ginepro makes Amarsebello a broth, but it tastes foul. Amarsebello asks Ginepro to make a stew with a pig's foot, and eager Ginepro consents to complete the task. He comes across a herd of pigs in the forest and thoughtlessly cuts off a pig's foot.

The Franciscans return from their excursion, only to be confronted by an angry peasant, who demands recompense. Francis orders Ginepro to apologize, which he does. The peasant, however, leaves in silence. Moments later, the peasant returns with the rest of the pig. He gives it to the Franciscans, and then orders them to never come near his pigs.

5 - How Francis, praying one night in the woods, met the leper.

Francis is lying alone in the woods, meditating on the passion and love of God, when he hears the sound of bells coming from a passing leper. He devotedly follows the leper, kissing and adoring him as the leper attempts to keep his distance. Filled with awe, Francis collapses on the ground, praising God for the encounter with the leper.

6 - How Brother Ginepro cooked enough food for two weeks, and Francis moved by his zeal gave him permission to preach.

Ginepro is tired of being left behind to cook supper for the brothers and wants to join them when they preach, so he and Giovanni cook all of the food that the Franciscans have accumulated into a broth that will last for two weeks. Francis, touched by this, grants Ginepro permission to preach, instructing him to begin each sermon with these words, "I talk and talk yet I accomplish little."

7 - How Brother Ginepro was judged on the gallows, and how his humility vanquished the ferocity of the tyrant Nicalaio.

This chapter focuses exclusively on Ginepro as he travels around Italy, trying to find someone who will listen to his preaching. He stumbles upon some children, who inform him that the tyrant Nicolaio has just occupied a neighbouring town. Excited by the new opportunity, Ginepro rushes to the village and attempts to preach to the barbarians. The barbarians, however, throw Ginepro around. It is in the midst of this abuse when Ginepro realises that he must preach not by words, but by example.

Ginepro is brought before the tyrant. The barbarians search him, and discover an awl and flint. Nicolaio, accusing Ginepro of being an assassin, orders the barbarians to beat Ginepro with clubs and prepare him for his execution. In mercy, the barbarians allow him to see a priest, who immediately recognizes him as a follower of Francis. The priest pleads with Nicolaio to spare Ginepro, but Nicolaio refuses; he was told that an assassin, disguised as a beggar, would kill him with an awl and flint, the very tools Ginepro possesses.

Nicolaio takes Ginepro into his tent and attempts to intimidate him to get the truth of the matter. As he gets increasingly flustered by Ginepro's humility, Nicolaio ultimately calls off the siege.

8 - How Brother Francis and Brother Leon experienced those things that are perfect happiness.

Perhaps the most famous chapter in I Fioretti, this parable explains how one can truly be happy. Francis and another Franciscan, Brother Leone, posit many scenarios that would be considered to bring happiness: restoring sight to the blind, healing the crippled, casting out demons, converting heretics, and the like. But after each scenario, Francis calmly explains that none of these acts would bring perfect happiness. Exasperated, Leone begs Francis finally to tell him what will really bring such happiness. Francis points to a building and hopes that the Lord will show them the perfect bliss Francis has in mind. They knock on the door and ask the peasant inside for alms. He refuses them, yet the friars persist, proclaiming that they wish to praise Jesus with him. The peasant drives the Franciscans out of the building, beating them with a club before leaving. Francis turns to Leone and explains that this is perfect happiness: to suffer and bear every evil deed out of love for Christ.

9 - How St. Francis left St. Mary of the Angels with his friars and traveled the world preaching peace.

Now it is time for the Franciscans to part, each called to go his own way to spread the message of the Gospel. They give away their land to the townsfolk and go to another town to give to the citizens all of their food. Once that's done, the friars take a moment to pray together one last time.

Francis leads the Franciscans into the woods, but they are unsure which direction to go. Francis instructs them to spin in circles until they fall over from dizziness. Whichever direction they face when they fall is the way they should go to preach. The Franciscans do just that, and they all depart, singing a chant as they travel the world to preach the peace of Christ.

Cast

- Brother Nazario Gerardi as Saint Francis of Assisi

- Brother Severino Pisacane as Brother Ginepro

- Esposito Bonaventura as Giovanni

- Aldo Fabrizi as Nicolaio, the tyrant

- Arabella Lemaître as Saint Clare of Assisi

- Brother Nazareno, Brother Raffaele and Brother Robert Sorrentino as Franciscans

- Gianfranco Bellini as the narrator

Production

Rossellini had been working on a film about St. Francis for years and he later called this film his favorite of his own works.[3] Rossellini and Federico Fellini wrote a treatment of the film that was 28 pages long and contained only 71 lines of dialogue. It was partially inspired by such St. Francis legends as the Fioretti and Life of Brother Ginepro. Rossellini said that it was not intended to be a bio-pic, but would focus on one specific aspect of st. Francis's personality: his whimsy. Rossellini described this aspect of St. Francis as "The Jester of God."[4] The film was a series of episodes from St. Francis's life and contained no plot or character development. Rossellini received funding from Angelo Rizzoli and from the Vatican to make the film.[4] He cast the same Franciscan monks who had appeared in his earlier film Paisà.[3] All of the other actors were also non-professionals, except for Aldo Fabrizi.[5]

Filming began on January 17, 1950[3] in the Italian countryside between Rome and Bracciano. Fellini was not present during the shooting and Rossellini depended on help with the films dialogue from Brunello Rondi and Father Alberto Maisano.[5] During the shooting Rossellini's and Ingrid Bergman's son Renato was born on February 2, 1950, although he was not officially divorced until February 9.[6] The film extras brought ricotta to the newborn baby during the production.[7]

Release and reception

The film premiered at the 1950 Venice Film Festival, where it was screened before a packed audience and often applauded in the middle of certain scenes. However, critics gave the film mostly poor reviews. Guido Aristarco said that it displayed a formalist and false reality.[8] Pierre Laprohon said that "its most obvious fault is its lack of realism."[9] Years after its release, Marcel Oms called it a "monument of stupidity."[10] However, The New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther praised it. On its initial release, the movie earned less than $13,000 in Italy.[11]

Pier Paolo Pasolini said that it was "among the most beautiful in Italian cinema" and Andrew Sarris ranked it eighth on his ten-best film list. François Truffaut called it "the most beautiful film in the world."[10]

Although somewhat poorly received at the time, the film is now recognized as a classic of world cinema. It has been released on DVD by The Criterion Collection[12] and Masters of Cinema.

In 1995, the Vatican listed the film as one of the forty-five greatest films ever made.[13]

References

- "The Flowers of Saint Francis." IMDb. 2010 Wed. 12 Oct 2010 <https://www.imdb.com>

- Bondanella, Peter. The Films of Roberto Rossellini. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991. 16-17. Print.

- Gallagher, Tag. The Adventures of Roberto Rossellini. New York: Da Capo Press. 1998. ISBN 0-306-80873-0. pp. 340.

- Gallagher. pp. 341.

- Gallagher. pp. 342.

- Gallagher. pp. 345.

- Gallagher. pp. 346.

- Gallagher. pp. 353.

- Gallagher. pp. 354.

- Gallagher. pp. 355.

- Gallagher. pp. 356.

- "The Flowers of St. Francis". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Steven D. Greydanus. "The Vatican Film List". Decent Films. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

External links

- The Flowers of St. Francis on IMDb

- The Flowers of St. Francis at AllMovie

- The Flowers of St. Francis at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Flowers of St. Francis at the Arts and Faith Top100 Spiritually Significant Films list

- CSFD ie Czechoslovak Film's Database

- The Flowers of St. Francis: God’s Jester an essay by Peter Brunette at the Criterion Collection

- Appreciation by Martin Scorsese for the Masters of Cinema DVD

- Vatican list of films