The Fall of Robespierre

The Fall of Robespierre is a three-act play written by Robert Southey and Samuel Coleridge in 1794. It follows the events in France after the downfall of Maximilien Robespierre. Robespierre is portrayed as a tyrant, but Southey's contributions praise him as a destroyer of despotism. The play does not operate as an effective drama for the stage, but rather as a sort of dramatic poem with each act being a different scene. According to Coleridge, "my sole aim to imitate the impassioned and highly figurative language of the French Orators and develop the characters of the chief actors on a vast stage of horrors."[1]

Background

To raise money, Southey and Coleridge began to work together in August 1794. According to Southey the project began in "sportive conversation" at the house of their friend Robert Lovell. The three intended to collaborate on a play that would deal with the beheading of Robespierre in July 1794. Their source was news articles that described the final moments of a dispute within the National Assembly. During composition, they were able to write 800 lines in just two days. The play was divided between the three collaborators, with Coleridge composing the first act, Southey composing the second act and Lovell the third. Southey and Lovell completed their acts but Coleridge had only finished part of his the following evening. Southey felt that Lowell's contribution was not "in keeping" and so rewrote the third act himself. Coleridge completed his act. When they turned to Joseph Cottle to publish the work, he refused and Coleridge had to search for another publisher. He took the manuscript to Cambridge, revising and improving his own contribution.[1] Eventually, the work was published in October 1794 by Benjamin Flower. Five hundred copies were printed and circulated in Bath, Cambridge, and London, which brought the writers fame while their personal relationship grew tense.[2]

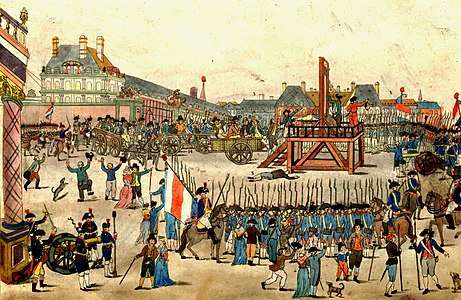

The events that inspired the work involve Robespierre's taking over of the National Assembly and removing the moderate members. During this time, he also allowed the executions of many individuals and became the center of power during the summer of 1793. The next summer, 28 July 1794, he was executed by guillotine along with 21 others.[3]

Play

The play is filled with various speeches on the topic of liberty. The first scene is set in the Tuileries, in which Bertrand Barère, Jean-Lambert Tallien and Louis Legendre, opponents of Robespierre discuss their plans to challenge the "tyrant". Their conversation comprises highly rhetorical speeches as if they were part of a public meeting.[4]

- The peaceful virtues

- And every blandishment of private life,

- The father's cares, the mother's fond endearment,

- All sacrificed to liberty's wild riot.

The third act, originally written by Lovell, was rewritten by Southey. Within the act, the opponents of Robespierre compare themselves to the assassins of Julius Caesar who are restoring the republic. In the final speech, Bertrand Barère discusses the history French Revolution and lists the various would-be despots who have attempted to usurp liberty for Louis XVI to Robespierre himself, concluding that France will be a beacon of liberation to the world.[5]

- Never, never,

- Shall this regenerated country wear

- The despot yoke. Though myriads round assail

- And with worse fury urge this new crusade

- Than savages have known; though all the leagued despots

- Depopulate all Europe, so to pour

- The accumulated mass upon our coasts,

- Sublime amidst the storm shall France arise

- And like the rock amid surrounding waves

- Repel the rushing ocean. — She shall wield

- The thunder-bolt of vengeance – She shall blast

- The despot's pride, and liberate the world.

Themes

Act one reflects Coleridge's feelings about those Robespierre executed, including Madame Roland and Brissot. The tone of the piece is not revolutionary, but it does include themes connected to his other works and reveals Coleridge's thoughts on marriage, politics, and childhood. It also incorporates Coleridge's view that individuals are naturally innocent in a manner similar to Rousseau's belief. This idea, combined with a belief in achieving some sort of paradise, was developed in the works following the play.[6]

The play as a whole deals with many Shakespearean themes and emphasises the precedents of both Brutus and Mark Antony throughout.[3] Southey's third act captures his feelings on the French Revolution and incorporates his radical views. The act also contains his feelings on despotism and liberty.[7]

Critical response

An anonymous review in the November 1794 Critical Review argued that the subject matter would have been appropriate for a tragedy but the events happened too soon to allow for it to be dealt with in an appropriate manner. The reviewer also commented on the haste of the work and that it "must, therefore, not be supposed to smell very strongly of the lamp.[8] However, the review does praise aspects of the poem, as the author writes, "By these free remarks, we mean not to under-rate Mr. Coleridge's historical drama. It affords ample testimony, that the writer is a genuine votary of the Muse, and several parts of it will afford much pleasure to those who can relish the beauties of poetry. Indeed a writer who could produce so much beauty in so little time, must possess powers that are capable of raising him to a distinguished place among the English poets."[8] In the British Critic, an anonymous reviewer argued in 1795 that "The sentiments ... in many instances are naturally, though boldly conceived, and expressed in language, which gives us reason to think the Author might, after some probation, become no unsuccessful wooer of the tragic muse."[9]

Notes

- Henry Nelson Coleridge, The Literary Remains of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, London, Pickering, 1836, pp. 2–3

- Holmes 1989 pp. 73–78

- Ashton 1997 p. 51

- Ashton 1997 pp. 51–52

- Speck 2006 pp. 45–46

- Holmes 1989 p. 74

- Speck 2006 p. 46

- Madden 1972 qtd. p. 37

- Madden 1972 qtd. p. 38

References

- Ashton, Rosemary. The Life of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Oxford: Blackwell, 1997.

- Holmes, Richard. Coleridge. New York: Pantheon Books, 1989.

- Madden, Lionel (ed). Robert Southey: The Critical Heritage. London: Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1972.

- Speck, W. A. Robert Southey. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.