The Day of the Locust (film)

The Day of the Locust is a 1975 American drama film directed by John Schlesinger, and starring Donald Sutherland, Karen Black, William Atherton, Burgess Meredith, Richard Dysart, John Hillerman, and Geraldine Page. Set in Hollywood, California just prior to World War II, the film depicts the alienation and desperation of a disparate group of individuals whose dreams of success have failed to come true. The screenplay by Waldo Salt is based on the 1939 novel of the same title by Nathanael West.

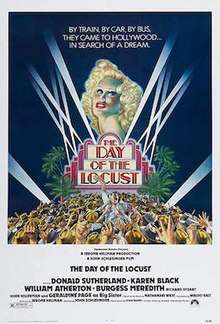

| The Day of the Locust | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Schlesinger |

| Produced by | Jerome Hellman |

| Screenplay by | Waldo Salt |

| Based on | The Day of the Locust by Nathanael West |

| Starring | |

| Music by | John Barry |

| Cinematography | Conrad L. Hall |

| Edited by | Jim Clark |

Production company | Long Road Productions |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 144 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

The film has garnered attention from scholars for its critical commentary on the film industry, as well as its nightmarish depiction of Hollywood, with some critics identifying implicit horror elements in the film's visuals.

Plot

Aspiring impressionist artist and recent Yale graduate Tod Hackett arrives in 1930s Hollywood to work as a painter at a major film studio. He rents an apartment in the San Bernardino Arms, a rundown apartment building occupied by various people, many on the fringes of the industry: Among them are Faye Greener, a tawdry aspiring actress; her father Harry, an ex-vaudevillian; Abe Kusich, a dwarf who carries on a tempestuous relationship with his girlfriend, Mary; Adore Loomis, a young boy whose mother is hoping to turn him into a child star; and Homer Simpson, a repressed accountant who lusts after Faye. Tod's unit has a crack in a wall caused by an earthquake; he puts a bright red flower in the crack. Tod befriends Faye, and attends a screening of a film in which she has a bit part, accompanied by Earle Shoop, a cowboy she is dating. Faye is disappointed with the film after finding that her appearance has been severely truncated. Tod attempts to romance Faye, but she coyly declines him, telling him she would only marry a rich man.

Tod attends a party at the Hollywood Hills mansion, where the partygoers indulge in watching stag films. Despite her hesitations, Faye continues to spend time with Tod. The two have a campfire in the desert with Earle and his friend, Miguel. A drunken Tod becomes enraged when Faye dances with Miguel, and chases after her, apparently to rape her, but she fends him off. Some time later, Faye and Homer take Harry to a holy roller church gathering led by a female preacher known as Big Sister, who performs a public "healing" of him in an attempt to cure his heart ailment, but he subsequently dies. In order to pay for Harry's funeral costs, Faye begins prostituting herself.

The shy, obsessive Homer continue to vie for Faye's affections, caring for her after her father's death. The two eventually move in together, and Faye continues to hopelessly find employment as a movie extra. While filming a Waterloo-themed period drama, Faye escapes injury during a violent collapse of the set, and reunites with Tod, who witnesses the accident. Faye and Homer subsequently invite Tod to dinner. The three attend a dinner theater featuring a drag show as entertainment. During the dinner, Faye confesses to Tod that her relationship with Homer is sexless, but is loving and offers her security. Later, Faye and Homer host a party attended by Tod, Abe, Earle, Miguel, and Claude Estee, a successful art director. Faye marauds about throughout the party, attempting to impress Claude and the other men. While outside, Homer observes the various men drunkenly fawning over Faye through a window. When Faye notices him, she accuses him of being a peeping tom before throwing a vase through the window. Shortly after, Homer walks in on Faye having sex with Miguel. Tod passively ignores the scene, but Earle discovers it and begins fighting with Miguel.

Later, the premiere of The Buccaneer is taking place at Grauman's Chinese Theater, attended by celebrities and a large crowd of civilians, including Faye. Tod, stuck in traffic due to the event, notices Homer walking aimlessly through the street. He attempts to talk to Homer, but Homer ignores him, seating himself on a bench near the theater. Adore, attending the premiere with his mother, begins pestering Homer before hitting him in the head with a rock. Enraged, Homer chases Adore through the crowd and into a parking lot. When Adore trips and falls, Homer begins violently stomping on him, crushing his bones and organs, effectively killing him. Adore's dying screams draw the attention of the crowd, who come upon Homer standing on the child's bloodied corpse. A mob subsequently pursues Homer, beating him viciously, and a full-blown riot soon breaks out. Meanwhile, an announcer at the premiere mistakes the action across the street for excitement over the film. Faye is assaulted in the melee, Tod suffers a compound fracture to his leg, and a car is flipped over, igniting a fire. As Tod observes the frenzy, he witnesses the apparitions of numerous faceless figures from his paintings descending on the scene.

On a morning shortly thereafter, Faye wanders into Tod's abandoned apartment. She sees everything was removed except for the flower in the wall crack, and her eyes well with tears.

Cast

- William Atherton as Tod Hackett

- Karen Black as Faye Greener

- Donald Sutherland as Homer Simpson

- Burgess Meredith as Harry Greener

- Geraldine Page as Big Sister

- Richard Dysart as Claude Estee

- John Hillerman as Ned Grote

- Bo Hopkins as Earle Shoop

- Pepe Serna as Miguel

- Lelia Goldoni as Mary Dove

- Billy Barty as Abe Kusich

- Jackie Earle Haley as Adore Loomis

- Gloria LeRoy as Mrs. Loomis

- Jane Hoffman as Mrs. Odlesh

- Norman Leavitt as Mr. Odlesh

- Madge Kennedy as Mrs. Johnson

- Natalie Schafer as Audrey Jennings

- Nita Talbot as Joan

- William Castle as the Director

Analysis

Film scholar M. Keith Booker views The Day of the Locust as "one of the nastiest film critiques ever produced of the film industry itself,"[1] that depicts Hollywood as a "nightmare realm dominated by images of commodified sex and violence."[2] Booker notes that the film aims to depict Hollywood and greater Los Angeles as a "dumping ground upon which broken dreams can be discarded to make way for the ever newer dreams constantly being turned out by the American Culture Industry."[2]

Lee Gambin of ComingSoon.net considers The Day of the Locust a "non-horror film that is secretly a horror film... a genuinely terrifying venture into the dark recesses of not only an industry that eats its product, vomits it back up and scoffs it down again, but a wonderful critique on human ugliness and desolation."[3]

Release

Box office

Released in the spring of 1975, The Day of the Locust was considered a box-office flop upon its release.[4]

Critical response

In his review in The New York Times, Vincent Canby called it "less a conventional film than it is a gargantuan panorama, a spectacle that illustrates West's dispassionate prose with a fidelity to detail more often found in a gimcracky Biblical epic than in something that so relentlessly ridicules American civilization... The movie is far from subtle, but it doesn't matter. It seems that much more material was shot than could be easily fitted into the movie, even at 144 minutes... It is reality projected as fantasy. Its grossness — its bigger-than-life quality — is so much a part of its style (and what West was writing about) that one respects the extravagances, the almost lunatic scale on which Mr. Schlesinger has filmed its key sequences."[5]

Jay Cocks of Time said; "The Day of the Locust looks puffy and overdrawn, sounds shrill because it is made with a combination of self-loathing and tenuous moral superiority. This is a movie turned out by the sort of mentality that West was mocking. Salt's adaptation... misses what is most crucial: West's tone of level rage and tilted compassion, his ability to make human even the most grotesque mockery."[6]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times called it a "daring, epic film... a brilliant one at times, and with a wealth of sharp-edged performances," citing that of Donald Sutherland as "one of the movie's wonders," although he expressed some reservations, noting that "somewhere on the way to its final vast metaphors, The Day of the Locust misplaces its concern with its characters. We begin to sense that they're marching around in response to the requirements of the story, instead of leading lives of their own. And so we stop worrying about them, because they're doomed anyway and not always because of their own shortcoming."[7]

In the Chicago Reader, Jonathan Rosenbaum described the film as "a painfully misconceived reduction and simplification... of the great Nathanael West novel about Hollywood... It misses crucial aspects of the book's surrealism and satire, though it has a fair number of compensations if you don't care about what's being ground underfoot - among them, Conrad Hall's cinematography and... one of Donald Sutherland's better performances."[8]

Channel 4 deemed it "fascinating, if flawed" and "by turns gaudy, bitter and occasionally just plain weird," adding "great performances and magnificent design make this a spectacular and highly entertaining film."[9]

Greg Ferrara for TCM, wrote "...every bit as powerful as any movie on the movie industry out there and, in my opinion, conveys the themes and metaphors of the book in exactly the right tone. They didn’t get it wrong at all, they got it perfectly right by telling the story, cinematically, in a very different way than the book. It’s harsh, brutal, cruel and unrelenting. I’ve rarely beheld a more pessimistic movie but it’s point, about all this fraud and hopelessness around us is both well-presented and well-taken."[10]

The film was shown at the 1975 Cannes Film Festival, but wasn't entered into the main competition.[11]

Accolades

| Award | Category | Recipient(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Award | Best Actor in a Supporting Role | Burgess Meredith | Nominated | [12] |

| Best Cinematography | Conrad L. Hall | Nominated | ||

| British Academy Film Awards | Best Costume Design | Ann Roth | Won | [13] |

| Best Supporting Actor | Burgess Meredith | Nominated | ||

| Best Art Direction | Richard Macdonald | Nominated | ||

| Golden Globe Award | Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama | Karen Black | Nominated | [14] |

| Best Supporting Actor | Burgess Meredith | Nominated | ||

See also

References

- Booker 2007, p. 120.

- Booker 2007, p. 121.

- Gambin, Lee (January 26, 2016). "Secretly Scary: 1975's The Day of the Locust". ComingSoon.net. Archived from the original on August 21, 2019.

- Lewis, Dan (October 24, 1976). "Dramamine dramas make a splash". The Record. Hackensack, New Jersey. p. B-26 – via Newspapers.com.

- Canby, Vincent (May 8, 1975). "'Day of Locust' Turns Dross Into Gold". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 21, 2019.

- Cocks, Jay (May 7, 1975). "Cinema: The 8th Plague". Time. Archived from the original on August 21, 2019.

- Ebert, Roger (May 23, 1975). "The Day of the Locust". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014.

- Rosenbaum, Jonathan. "The Day of the Locust". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on April 7, 2013.

- "The Day of the Locust". Channel 4. Archived from the original on December 9, 2004.

- Ferrara, Greg (27 February 2012). "Too Big to Fail and yet…". Movie Morlocks via web.archive.org. TCM. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- "Festival de Cannes: The Day of the Locust". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- "Oscars Database Search: The Day of the Locust". Academy Awards. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on August 21, 2019.

- "Film in 1976". British Academy Film Awards. British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014.

- "Day of the Locust, The". Golden Globe Awards. Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on August 21, 2019.

Sources

- Booker, M. Keith (2007). From Box Office to Ballot Box: The American Political Film. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-99122-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tibbetts, John C., and James M. Welsh, eds. The Encyclopedia of Novels Into Film (2nd ed. 2005) pp 91–93.