The Bookworm (painting)

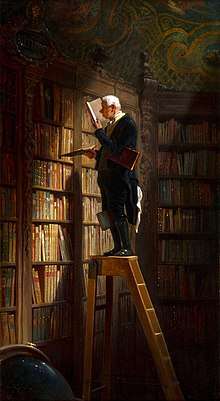

The Bookworm (German: Der Bücherwurm) is an oil-on-canvas painting by the German painter and poet Carl Spitzweg. The picture was made circa 1850 and is typical of Spitzweg's humorous, anecdotal style and it is characteristic of Biedermeier art in general.[1] The painting is representative of the introspective and conservative mood in Europe during the period between the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the revolutions of 1848, but at the same time pokes fun at those attitudes by embodying them in the fusty old scholar unconcerned with the affairs of the mundane world.

| The Bookworm | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Carl Spitzweg |

| Year | c. 1850 |

| Medium | Oil-on-canvas |

| Dimensions | 49.5 cm × 26.8 cm (19 1⁄2 in × 10 1⁄2 in) |

| Location | Museum Georg Schäfer, Schweinfurt, Germany |

History

Carl Spitzweg painted three variations of this piece. The first, painted ca. 1850, was listed under the title of The Librarian and sold in Vienna to Ignaz Kuranda in 1852 and now belongs to the collection of the Museum Georg Schäfer in Schweinfurt. An exemplar of the same dimensions was painted by Spitzweg a year later and sent for sale to his New York art dealer HW Schaus. This exemplar found its way into René Schleinitz's art collection and was bequeathed to the Milwaukee Public Library and housed in their Central Library (Milwaukee, Wisconsin).[2] In December 2014, the painting was placed on permanent loan to the Grohmann Museum at Milwaukee School of Engineering in Milwaukee. A final version of the piece was painted in 1884.[3]

Analysis

The picture shows an untidily dressed elderly bibliophile standing on top of a library ladder with several large volumes jammed under his arms and between his legs as he peers short-sightedly at a book. Unaware of his apparently princely or abbatial Baroque surroundings, he is totally absorbed in his researches. A handkerchief, carelessly replaced, trails from his pocket. His black knee-breeches suggest a courtly status.[4] The intensity with which he stares at his book in the dusty old once-glorious library with its frescoed ceiling mirrors the inward-looking attitudes and return to conservative values that affected Europe during the period. The painting was executed two years after the revolutions of 1848 provided a shock to the stable world embodied in the dusty solitude of the library. In the lower left corner of the painting an old faded globe can be seen; the bookworm is not interested in the outside world, but in the knowledge of the past. He is illuminated with the soft golden light that is a hallmark of Spitzweg's work,[5] but the scholar's interest in the light streaming from the unseen window extends only so far as it allows him to see the words on the pages of his old books. The height of the library ladder can only be estimated: the globe suggests a possible floor height, but none of the floor is visible, heightening the sense of precariousness of the oblivious scholar's position. Equally the size of the library is unknown; the old man is consulting books from the section of "Metaphysics" (Metaphysik)—indicated by the plaque on the highly ornamented bookcase—which both suggests a vast library and underlines the otherworldliness of the book lover.

While obviously political or polemical art was discouraged by the conservative attitudes that pervaded Central Europe, and more parochial themes were chosen by the artists of the Biedermeier period than had been the vogue in the Romantic period that preceded it, there was still room for subtle allusions and light satire.[6] Spitzweg's paintings poke gentle fun at the figures he saw around him. He was almost entirely self-taught and although his techniques were developed by copying the Dutch Masters, his portrayal of his subjects is believed to have been influenced by the works of William Hogarth and Honoré Daumier. Although The Bookworm is among the most obviously satirical of his works and though none of his paintings show the cruel wit of Hogarth, there are parallels between the characters of Hogarth and those depicted by Spitzweg; the bookworm—carefully observed and knowingly detailed—would not look out of place in a scene from Marriage à-la-mode; indeed, Spitzweg is sometimes referred to as a "German Hogarth".[5]

See also

Notes

- Fritz Novotny, Painting and Sculpture in Europe 1780-1880, p. 227, Yale University Press, 1992.

- "Richard E. and Lucile Krug Rare Books Room". Mpl.org. Archived from the original on 2013-08-07. Retrieved 2013-11-17.

- Jens Christian Jensen

- See Court uniform and dress.

- Flockhart p. 406

- Eckhard p. 163

References

- Bernstein, Eckhard (2004). Culture and Customs of Germany. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313322031.

- Farthing, Stephen (2006). 1001 Paintings You Must See Before You Die. London: Quintet Publishing Ltd. p. 960. ISBN 1844035638.

- Jensen, Jens Christian (2007). Carl Spitzweg. Munich: Prestel Verlag. ISBN 3791337475.

Further reading

- Müller, Kristiane; Urban, Eberhard: Carl Spitzweg — Beliebte und unbekannte Bilder nebst Zeichnungen und Studien ergänzt durch Gedichte und Briefe, Zeugnisse und Dokumente. Edition Aktuell.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carl Spitzweg - Der Bücherwurm. |