Allotropes of phosphorus

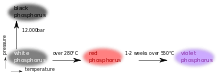

Elemental phosphorus can exist in several allotropes, the most common of which are white and red solids. Solid violet and black allotropes are also known. Gaseous phosphorus exists as diphosphorus and atomic phosphorus.

White phosphorus

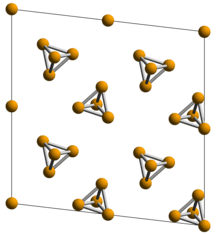

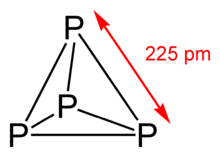

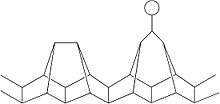

White phosphorus, yellow phosphorus or simply tetraphosphorus (P4) exists as molecules made up of four atoms in a tetrahedral structure. The tetrahedral arrangement results in ring strain and instability. The molecule is described as consisting of six single P–P bonds. Two different crystalline forms are known. The α form is defined as the standard state of the element, but is actually metastable under standard conditions.[1] It has a body-centered cubic crystal structure, and transforms reversibly into the β form at 195.2 K. The β form is believed to have a hexagonal crystal structure.[2]

White phosphorus is a translucent waxy solid that quickly becomes yellow when exposed to light. For this reason it is also called yellow phosphorus. It glows greenish in the dark (when exposed to oxygen) and is highly flammable and pyrophoric (self-igniting) upon contact with air. It is toxic, causing severe liver damage on ingestion and phossy jaw from chronic ingestion or inhalation. The odour of combustion of this form has a characteristic garlic smell, and samples are commonly coated with white "diphosphorus pentoxide", which consists of P4O10 tetrahedral with oxygen inserted between the phosphorus atoms and at their vertices. White phosphorus is only slightly soluble in water and can be stored under water. Indeed, white phosphorus is safe from self-igniting only when it is submerged in water. It is soluble in benzene, oils, carbon disulfide, and disulfur dichloride.

Production and applications

The white allotrope can be produced using several different methods. In the industrial process, phosphate rock is heated in an electric or fuel-fired furnace in the presence of carbon and silica.[3] Elemental phosphorus is then liberated as a vapour and can be collected under phosphoric acid. An idealized equation for this carbothermal reaction is shown for calcium phosphate (although phosphate rock contains substantial amounts of fluoroapatite):

- 2 Ca3(PO4)2 + 6 SiO2 + 10 C → 6 CaSiO3 + 10 CO + P4

White phosphorus has an appreciable vapour pressure at ordinary temperatures. The vapour density indicates that the vapour is composed of P4 molecules up to about 800 °C. Above that temperature, dissociation into P2 molecules occurs.

It ignites spontaneously in air at about 50 °C (122 °F), and at much lower temperatures if finely divided. This combustion gives phosphorus (V) oxide:

- P

4 + 5 O

2 → P

4O

10

Because of this property, white phosphorus is used as a weapon.

Non-existence of cubic-P8

Although white phosphorus converts to the thermodynamically more stable red allotrope, the formation of the cubic P8 molecule is not observed in the condensed phase. Analogs of this hypothetical molecule have been prepared from phosphaalkynes.[4] White phosphorus in the gaseous state and as waxy solid consists of reactive P4 molecules.

Red phosphorus

Red phosphorus may be formed by heating white phosphorus to 300 °C (572 °F) in the absence of air or by exposing white phosphorus to sunlight. Red phosphorus exists as an amorphous network. Upon further heating, the amorphous red phosphorus crystallizes. Red phosphorus does not ignite in air at temperatures below 240 °C (464 °F), whereas pieces of white phosphorus ignite at about 30 °C (86 °F). Ignition is spontaneous at room temperature with finely divided material as the high surface area allows the surface oxidation to rapidly heat the sample to the ignition temperature.

Under standard conditions it is more stable than white phosphorus, but less stable than the thermodynamically stable black phosphorus. The standard enthalpy of formation of red phosphorus is -17.6 kJ/mol.[1] Red phosphorus is kinetically most stable.

Applications

Red phosphorus can be used as a very effective flame retardant, especially in thermoplastics (e.g. polyamide) and thermosets (e.g. epoxy resins or polyurethanes). The flame retarding effect is based on the formation of polyphosphoric acid. Together with the organic polymer material, this acid creates a char which prevents the propagation of the flames. The safety risks associated with phosphine generation and friction sensitivity of red phosphorus can be effectively reduced by stabilization and micro-encapsulation. For easier handling, red phosphorus is often used in form of dispersions or masterbatches in various carrier systems. However, for electronic/electrical systems, red phosphorus flame retardant has been effectively banned by major OEMs due to its tendency to induce premature failures.[5] There have been two issues over the years: the first was red phosphorus in epoxy molding compounds inducing elevated leakage current in semiconductor devices[6] and the second was acceleration of hydrolysis reactions in PBT insulating material.[7]

Red phosphorus can also be used in the illicit production of narcotics, including some recipes for methamphetamine.

Red phosphorus can be used as an elemental photocatalyst for hydrogen formation from the water.[8] They display a steady hydrogen evolution rates of 633ℳmol/(h•g) by the formation of small-sized fibrous phosphorus.[9]

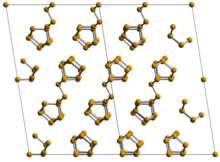

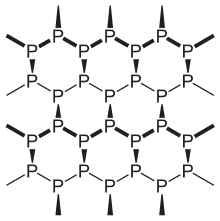

Hittorf's violet phosphorus

Monoclinic phosphorus, or violet phosphorus, is also known as Hittorf's metallic phosphorus.[10][11] In 1865, Johann Wilhelm Hittorf heated red phosphorus in a sealed tube at 530 °C. The upper part of the tube was kept at 444 °C. Brilliant opaque monoclinic, or rhombohedral, crystals sublimed as a result. Violet phosphorus can also be prepared by dissolving white phosphorus in molten lead in a sealed tube at 500 °C for 18 hours. Upon slow cooling, Hittorf's allotrope crystallises out. The crystals can be revealed by dissolving the lead in dilute nitric acid followed by boiling in concentrated hydrochloric acid.[12] In addition, a fibrous form exists with similar phosphorus cages. The lattice structure of violet phosphorus was presented by Thurn and Krebs in 1969.[13] Imaginary frequencies, indicating the irrationalities or instabilities of the structure, were obtained for the reported violet structure from 1969.[14] The single crystal of violet phosphorus was also produced. The lattice structure of violet phosphorus has been obtained by single‐crystal x‐ray diffraction to be monoclinic with space group of P2/n (13) (a=9.210, b=9.128, c=21.893 Å, β=97.776°, CSD-1935087). The optical band gap of the violet phosphorus was measured by diffuse reflectance spectroscopy to be around 1.7 eV. The thermal decomposition temperature was 52 °C higher than its black phosphorus counterpart. The violet phosphorene was easily obtained from both mechanical and solution exfoliation.

Reactions of violet phosphorus

It does not ignite in air until heated to 300 °C and is insoluble in all solvents. It is not attacked by alkali and only slowly reacts with halogens. It can be oxidised by nitric acid to phosphoric acid.

If it is heated in an atmosphere of inert gas, for example nitrogen or carbon dioxide, it sublimes and the vapour condenses as white phosphorus. If it is heated in a vacuum and the vapour condensed rapidly, violet phosphorus is obtained. It would appear that violet phosphorus is a polymer of high relative molecular mass, which on heating breaks down into P2 molecules. On cooling, these would normally dimerize to give P4 molecules (i.e. white phosphorus) but, in a vacuum, they link up again to form the polymeric violet allotrope.

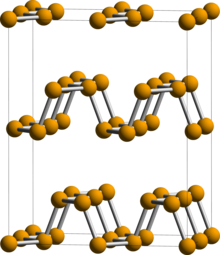

Black phosphorus

Black phosphorus is the thermodynamically stable form of phosphorus at room temperature and pressure, with a heat of formation of -39.3 kJ/mol (relative to white phosphorus which is defined as the standard state).[1] It was first synthesized by heating white phosphorus under high pressures (12,000 atmospheres) in 1914. As a 2D material, in appearance, properties, and structure, black phosphorus is very much like graphite with both being black and flaky, a conductor of electricity, and having puckered sheets of linked atoms.[15] Phonons, photons, and electrons in layered black phosphorus structures behave in a highly anisotropic manner within the plane of layers, exhibiting strong potential for applications to thin film electronics and infrared optoelectronics.[16]

Black phosphorus has an orthorhombic pleated honeycomb structure and is the least reactive allotrope, a result of its lattice of interlinked six-membered rings where each atom is bonded to three other atoms.[17][18] Black and red phosphorus can also take a cubic crystal lattice structure.[19] The first high-pressure synthesis of black phosphorus crystals was made by the physicist Percy Williams Bridgman in 1914.[20] A recent synthesis of black phosphorus using metal salts as catalysts has been reported.[21]

Phosphorene

The similarities to graphite also include the possibility of scotch-tape delamination (exfoliation), resulting in phosphorene, a graphene-like 2D material with excellent charge transport properties, thermal transport properties and optical properties. Distinguishing features of scientific interest include a thickness dependent band-gap, which is not found in graphene.[22] This, combined with a high on/off ratio of ~105 makes phosphorene a promising candidate for field-effect transistors (FETs).[23] The tunable bandgap also suggests promising applications in mid-infrared photodetectors and LEDs.[24] Highly anisotropic thermal conductivity has been measured in three major principal crystal orientations and is effected by strain applied across the lattice.[25][26] Exfoliated black phosphorus sublimes at 400 °C in vacuum.[27] It gradually oxidizes when exposed to water in the presence of oxygen, which is a concern when contemplating it as a material for the manufacture of transistors, for example.[28][29]

Ring-shaped phosphorus

Ring-shaped phosphorus was theoretically predicted in 2007.[30] The ring-shaped phosphorus was self-assembled inside evacuated multi-walled carbon nanotubes with inner diameters of 5–8 nm using a vapor encapsulation method. A ring with a diameter of 5.30 nm, consisting of 23P8 and 23P2 units with a total of 230P atoms, was observed inside a multi-walled carbon nanotube with an inner diameter of 5.90 nm in atomic scale. The distance between neighboring rings is 6.4 Å.[31]

Blue phosphorus

Single-layer blue phosphorus was first produced in 2016 by the method of molecular beam epitaxy from black phosphorus as precursor.[32]

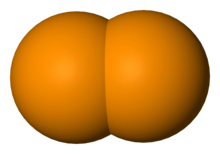

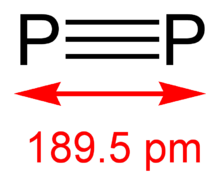

Diphosphorus

The diphosphorus allotrope (P2) can normally be obtained only under extreme conditions (for example, from P4 at 1100 kelvin). In 2006, the diatomic molecule was generated in homogenous solution under normal conditions with the use of transition metal complexes (for example, tungsten and niobium).[33]

Diphosphorus is the gaseous form of phosphorus, and the thermodynamically stable form between 1200 °C and 2000 °C. The dissociation of tetraphosphorus (P

4) begins at lower temperature: the percentage of P

2 at 800 °C is ≈ 1%. At temperatures above about 2000 °C, the diphosphorus molecule begins to dissociate into atomic phosphorus.

Phosphorus nanorods

P12 nanorod polymers were isolated from CuI-P complexes using low temperature treatment.[34]

Red/brown phosphorus was shown to be stable in air for several weeks and have significantly different properties from red phosphorus. Electron microscopy showed that red/brown phosphorus forms long, parallel nanorods with a diameter between 3.4 Å and 4.7 Å.[34]

Properties

| Form | white(α) | white(β) | violet | black |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry | Body-centred cubic | Triclinic | Monoclinic | Orthorhombic |

| Pearson symbol | aP24 | mP84 | oS8 | |

| Space group | I43m | P1 No.2 | P2/c No.13 | Cmca No.64 |

| Density (g/cm3) | 1.828 | 1.88 | 2.36 | 2.69 |

| Bandgap (eV) | 2.1 | 1.5 | 0.34 | |

| Refractive index | 1.8244 | 2.6 | 2.4 |

See also

References

- Housecroft, C. E.; Sharpe, A. G. (2004). Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 392. ISBN 978-0-13-039913-7.

- Durif, M.-T. Averbuch-Pouchot; A. (1996). Topics in phosphate chemistry. Singapore [u.a.]: World Scientific. p. 3. ISBN 978-981-02-2634-3.

- Threlfall, R.E., (1951). 100 years of Phosphorus Making: 1851–1951. Oldbury: Albright and Wilson Ltd

- Streubel, Rainer (1995). "Phosphaalkyne Cyclooligomers: From Dimers to Hexamers—First Steps on the Way to Phosphorus–Carbon Cage Compounds". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 34 (4): 436–438. doi:10.1002/anie.199504361.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-01-02. Retrieved 2018-01-01.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Craig Hillman, Red Phosphorus Induced Failures in Encapsulated Circuits, https://www.dfrsolutions.com/hubfs/Resources/services/Red-Phosphorus-Induced-Failures-in-Encapsulated-Circuits.pdf?t=1513022462214

- Dock Brown, The Return of the Red Retardant, SMTAI 2015, https://www.dfrsolutions.com/hubfs/Resources/services/The-Return-of-the-Red-Retardant.pdf?t=1513022462214

- Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 2012, 111-112, 409-414.

- Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2016, 55, 9580-9585.

- Curry, Roger (2012-07-08). "Hittorf's Metallic Phosphorus of 1865". LATERAL SCIENCE. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- Monoclinic phosphorus formed from vapor in the presence of an alkali metal U.S. Patent 4,620,968

- Hittorf, W. (1865). "Zur Kenntniss des Phosphors". Annalen der Physik. 202 (10): 193–228. Bibcode:1865AnP...202..193H. doi:10.1002/andp.18652021002.

- Thurn, H.; Krebs, H. (1969-01-15). "Über Struktur und Eigenschaften der Halbmetalle. XXII. Die Kristallstruktur des Hittorfschen Phosphors". Acta Crystallographica Section B (in German). 25 (1): 125–135. doi:10.1107/S0567740869001853. ISSN 0567-7408.

- Zhang, Lihui; Huang, Hongyang; Zhang, Bo; Gu, Mengyue; Zhao, Dan; Zhao, Xuewen; Li, Longren; Zhou, Jun; Wu, Kai; Cheng, Yonghong; Zhang, Jinying (2020). "Structure and Properties of Violet Phosphorus and Its Phosphorene Exfoliation". Angewandte Chemie. 132 (3): 1090–1096. doi:10.1002/ange.201912761. ISSN 1521-3757.

- Korolkov, Vladimir V.; Timokhin, Ivan G.; Haubrichs, Rolf; Smith, Emily F.; Yang, Lixu; Yang, Sihai; Champness, Neil R.; Schröder, Martin; Beton, Peter H. (2017-11-09). "Supramolecular networks stabilise and functionalise black phosphorus". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 1385. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8.1385K. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01797-6. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5680224. PMID 29123112.

- Allain, A.; Kang, J.; Banerjee, K.; Kis, A. (2015). "Electrical contacts to two-dimensional semiconductors". Nat. Mater. 14 (12): 1195–1205. doi:10.1038/nmat4452.

- Brown, A.; Rundqvist, S. (1965). "Refinement of the crystal structure of black phosphorus". Acta Crystallographica. 19 (4): 684–685. doi:10.1107/S0365110X65004140.

- Cartz, L.; Srinivasa, S. R.; Riedner, R. J.; Jorgensen, J. D.; Worlton, T. G. (1979). "Effect of pressure on bonding in black phosphorus". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 71 (4): 1718. Bibcode:1979JChPh..71.1718C. doi:10.1063/1.438523.

- Ahuja, Rajeev (2003). "Calculated high pressure crystal structure transformations for phosphorus". Physica Status Solidi B. 235 (2): 282–287. Bibcode:2003PSSBR.235..282A. doi:10.1002/pssb.200301569.

- Bridgman, P. W. (1914-07-01). "Two New Modifications of Phosphorus". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 36 (7): 1344–1363. doi:10.1021/ja02184a002. ISSN 0002-7863.

- Lange, Stefan; Schmidt, Peer; Nilges, Tom (2007). "Au3SnP7@Black Phosphorus: An Easy Access to Black Phosphorus". Inorganic Chemistry. 46 (10): 4028–35. doi:10.1021/ic062192q. PMID 17439206.

- "Black Phosphorus Powder and Crystals". Ossila. Retrieved 2019-08-23.

- Zhang, Yuanbo; Chen, Xian Hui; Feng, Donglai; Wu, Hua; Ou, Xuedong; Ge, Qingqin; Ye, Guo Jun; Yu, Yijun; Li, Likai (May 2014). "Black phosphorus field-effect transistors". Nature Nanotechnology. 9 (5): 372–377. arXiv:1401.4117. Bibcode:2014NatNa...9..372L. doi:10.1038/nnano.2014.35. ISSN 1748-3395. PMID 24584274.

- Wang, J.; Rousseau, A.; Yang, M.; Low, T.; Francoeur, S.; Kéna-Cohen, S. "Mid-infrared Polarized Emission from Black Phosphorus Light-Emitting Diodes". Nano Letters. 20 (5): 3651–3655. arXiv:1911.09184. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c00581. PMID 32286837.

- Kang, J.; Ke, M.; Hu, Y. (2017). "Ionic Intercalation in Two-Dimensional van der Waals Materials: In Situ Characterization and Electrochemical Control of the Anisotropic Thermal Conductivity of Black Phosphorus". Nano Letters. 17 (3): 1431–1438. Bibcode:2017NanoL..17.1431K. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b04385. PMID 28231004.

- Smith, B.; Vermeersch, B.; Carrete, J.; Ou, E.; Kim, J.; Li, S. (2017). "Temperature and Thickness Dependences of the Anisotropic In-Plane Thermal Conductivity of Black Phosphorus". Adv Mater. 29 (5): 1603756. doi:10.1002/adma.201603756. PMID 27882620.

- Liu, Xiaolong D.; Wood, Joshua D.; Chen, Kan-Sheng; Cho, EunKyung; Hersam, Mark C. (9 February 2015). "In Situ Thermal Decomposition of Exfoliated Two-Dimensional Black Phosphorus". Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 6 (5): 773–778. arXiv:1502.02644. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b00043. PMID 26262651.

- Wood, Joshua D.; Wells, Spencer A.; Jariwala, Deep; Chen, Kan-Sheng; Cho, EunKyung; Sangwan, Vinod K.; Liu, Xiaolong; Lauhon, Lincoln J.; Marks, Tobin J.; Hersam, Mark C. (7 November 2014). "Effective Passivation of Exfoliated Black Phosphorus Transistors against Ambient Degradation". Nano Letters. 14 (12): 6964–6970. arXiv:1411.2055. Bibcode:2014NanoL..14.6964W. doi:10.1021/nl5032293. PMID 25380142.

- Wu, Ryan J.; Topsakal, Mehmet; Low, Tony; Robbins, Matthew C.; Haratipour, Nazila; Jeong, Jong Seok; Wentzcovitch, Renata M.; Koester, Steven J.; Mkhoyan, K. Andre (2015-11-01). "Atomic and electronic structure of exfoliated black phosphorus". Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology A. 33 (6): 060604. doi:10.1116/1.4926753. ISSN 0734-2101.

- Karttunen, Antti J.; Linnolahti, Mikko; Pakkanen, Tapani A. (15 June 2007). "Icosahedral and Ring-Shaped Allotropes of Phosphorus". Chemistry - A European Journal. 13 (18): 5232–5237. doi:10.1002/chem.200601572. PMID 17373003.

- Zhang, Jinying; Zhao, Dan; Xiao, Dingbin; Ma, Chuansheng; Du, Hongchu; Li, Xin; Zhang, Lihui; Huang, Jialiang; Huang, Hongyang; Jia, Chun-Lin; Tománek, David; Niu, Chunming (6 February 2017). "Assembly of Ring-Shaped Phosphorus within Carbon Nanotube Nanoreactors". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 56 (7): 1850–1854. doi:10.1002/anie.201611740. PMID 28074606.

- Zhang, Jia Lin; Zhao, Songtao and 10 others (30 June 2016). "Epitaxial Growth of Single Layer Blue Phosphorus: A New Phase of Two-Dimensional Phosphorus". Nano Letters. 16 (8): 4903–4908. Bibcode:2016NanoL..16.4903Z. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b01459. PMID 27359041.

- Piro, Na; Figueroa, Js; Mckellar, Jt; Cummins, Cc (2006). "Triple-bond reactivity of diphosphorus molecules". Science. 313 (5791): 1276–9. Bibcode:2006Sci...313.1276P. doi:10.1126/science.1129630. PMID 16946068.

- Pfitzner, A; Bräu, Mf; Zweck, J; Brunklaus, G; Eckert, H (Aug 2004). "Phosphorus nanorods – two allotropic modifications of a long-known element". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 43 (32): 4228–31. doi:10.1002/anie.200460244. PMID 15307095.

- A. Holleman; N. Wiberg (1985). "XV 2.1.3". Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (33 ed.). de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-012641-9.

- Berger, L. I. (1996). Semiconductor materials. CRC Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-8493-8912-2.

External links

- White phosphorus

- White Phophorus at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- More about White Phosphorus (and phosphorus pentoxide) at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)