Turpentine

Turpentine (which is also called spirit of turpentine, oil of turpentine, wood turpentine, terebenthene, terebinthine and (colloquially), turps)[3] is a fluid obtained by the distillation of resin harvested from living trees, mainly pines. It is mainly used as a solvent, and as a source of material for organic syntheses.

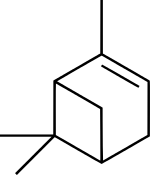

Chemical structure of α-pinene, a major component of turpentine | |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.407 |

| EC Number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| Properties | |

| C10H16 | |

| Molar mass | 136.238 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Viscous liquid[1] |

| Odor | Resinous[1] |

| Melting point | −55[1] °C (−67 °F; 218 K) |

| Boiling point | 154[1] °C (309 °F; 427 K) |

| 20 mg/L [1] | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS pictograms |     |

| GHS Signal word | Danger |

| Flash point | 35[1] °C (95 °F; 308 K) |

| 220[1] °C (428 °F; 493 K) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Turpentine is composed of terpenes, primarily the monoterpenes alpha- and beta-pinene, with lesser amounts of carene, camphene, dipentene, and terpinolene.[4]

The word turpentine derives (via French and Latin), from the Greek word τερεβινθίνη terebinthine, in turn the feminine form (to conform to the feminine gender of the Greek word, which means "resin") of an adjective (τερεβίνθινος) derived from the Greek noun (τερέβινθος), for the tree species terebinth[5] Mineral turpentine or other petroleum distillates are used to replace turpentine -- although their chemistries are very different.[6]

Source trees

One of the earliest sources of turpentine was the terebinth or turpentine tree (Pistacia terebinthus), a Mediterranean tree related to the pistachio. Important pines for turpentine production include: maritime pine (Pinus pinaster), Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis), Masson's pine (Pinus massoniana), Sumatran pine (Pinus merkusii), longleaf pine (Pinus palustris), loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) and ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa).

Canada balsam, also called Canada turpentine or balsam of fir, is a turpentine which is made from the oleoresin of the balsam fir. Venice turpentine is produced from the western larch Larix occidentalis.

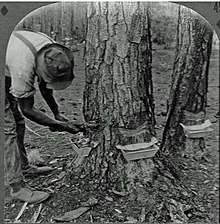

To tap into the sap producing layers of the tree, turpentiners used a combination of hacks to remove the pine bark. Once debarked, pine trees secrete oleoresin onto the surface of the wound as a protective measure to seal the opening, resist exposure to micro-organisms and insects, and prevent vital sap loss. Turpentiners wounded trees in V-shaped streaks down the length of the trunks to channel the oleoresin into containers. It was then collected and processed into spirits of turpentine. Oleoresin yield may be increased by as much as 40% by applying paraquat herbicides to the exposed wood.[7]

The V-shaped cuts are called "catfaces" for their resemblance to a cat's whiskers. These marks on a pine tree signify it was used to collect resin for turpentine production.[8]

Converting oleoresin to turpentine

Crude oleoresin collected from wounded trees may be evaporated by steam distillation in a copper still. Molten rosin remains in the still bottoms after turpentine has been evaporated and recovered from a condenser.[7] Turpentine may alternatively be condensed from destructive distillation of pine wood.[4]

Oleoresin may also be extracted from shredded pine stumps, roots, and slash using the light end of the heavy naphtha fraction (boiling between 90 and 115 °C or 195 and 240 °F) from a crude oil refinery. Multi-stage counter-current extraction is commonly used so fresh naphtha first contacts wood leached in previous stages and naphtha laden with turpentine from previous stages contacts fresh wood before vacuum distillation to recover naphtha from the turpentine. Leached wood is steamed for additional naphtha recovery prior to burning for energy recovery.[9]

When producing chemical wood pulp from pines or other coniferous trees, sulfate turpentine may be condensed from the gas generated in Kraft process pulp digesters. The average yield of crude sulfate turpentine is 5–10 kg/t pulp.[10] Unless burned at the mill for energy production, sulfate turpentine may require additional treatment measures to remove traces of sulfur compounds.[11]

Industrial and other end uses

Solvent

The two primary uses of turpentine in industry are as a solvent and as a source of materials for organic synthesis. As a solvent, turpentine is used for thinning oil-based paints, for producing varnishes, and as a raw material for the chemical industry. Its industrial use as a solvent in industrialized nations has largely been replaced by the much cheaper turpentine substitutes distilled from crude oil. Turpentine has long been used as a solvent, mixed with beeswax or with carnauba wax, to make fine furniture wax for use as a protective coating over oiled wood finishes (e.g., tung oil).

Source of organic compounds

Turpentine is also used as a source of raw materials in the synthesis of fragrant chemical compounds. Commercially used camphor, linalool, alpha-terpineol, and geraniol are all usually produced from alpha-pinene and beta-pinene, which are two of the chief chemical components of turpentine. These pinenes are separated and purified by distillation. The mixture of diterpenes and triterpenes that is left as residue after turpentine distillation is sold as rosin.

Medicinal elixir

Turpentine and petroleum distillates such as coal oil and kerosene have been used medicinally since ancient times, as topical and sometimes internal home remedies. Topically, it has been used for abrasions and wounds, as a treatment for lice, and when mixed with animal fat it has been used as a chest rub, or inhaler for nasal and throat ailments.[12] Many modern chest rubs, such as the Vicks variety, still contain turpentine in their formulations.

Turpentine, now understood to be dangerous for consumption, was a common medicine among seamen during the Age of Discovery. It is one of several products carried aboard Ferdinand Magellan's fleet in his first circumnavigation of the globe.[13] Taken internally it was used as a treatment for intestinal parasites. This is dangerous, due to the chemical's toxicity.[14][15]

Turpentine enemas, a very harsh purgative, had formerly been used for stubborn constipation or impaction.[16] Turpentine enemas were also given punitively to political dissenters in post-independence Argentina.[17]

Niche uses

- Turpentine is also added to many cleaning and sanitary products due to its antiseptic properties and its "clean scent".

- In early 19th-century America, turpentine was sometimes burned in lamps as a cheap alternative to whale oil. It was most commonly used for outdoor lighting, due to its strong odour.[18] A blend of ethanol and turpentine called camphine served as the dominant lamp fuel replacing whale oil until the arrival of kerosene.[19]

- In 1946, Soichiro Honda fueled the first Honda motorcycles with turpentine, due to the scarcity of gasoline in Japan following World War II.[20]

- In his Book If Only They Could Talk, veterinarian and author James Herriot describes the use of its reaction with resublimed iodine to "drive the iodine into the tissue" - or perhaps just impress the watching customer with a spectacular treatment.[21]

- Turpentine was added extensively into gin during the Gin Craze.[22]

Hazards

| NFPA 704 fire diamond | |

|---|---|

As an organic solvent, its vapour can irritate the skin and eyes, damage the lungs and respiratory system, as well as the central nervous system when inhaled, and cause damage to the renal system when ingested, among other things.[23] Being combustible, it also poses a fire hazard. While it is a fire hazard, in large quantities turpentine can be used to smother and extinguish flames due to its liquid state. Ingestion can cause burning sensations, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, confusion, convulsions, diarrhea, and unconsciousness.[24] Because turpentine can cause spasms of the airways particularly in people with asthma and whooping cough, it can contribute to a worsening of breathing issues in persons with these diseases if inhaled.

People can be exposed to turpentine in the workplace by breathing it in, skin absorption, swallowing it, and eye contact. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has set the legal limit (permissible exposure limit) for turpentine exposure in the workplace as 100 ppm (560 mg/m3) over an 8-hour workday. The same threshold was adopted by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) as the recommended exposure limit (REL). At levels of 8000 ppm (4,448 mg/m3), turpentine is immediately dangerous to life and health.[25]

See also

- Charles Herty – Chemist, academic, businessman, football coach

- Galipot

- Naval stores industry

- Patent medicine

- Retsina – A resinated wine from Greece

- Russia leather, a water-resistant leather, using a birch oil distillate similar to turpentine in its manufacture.

- White spirit, also known as Turpentine substitute – Petroleum-derived clear, transparent liquid / / Mineral spirit

Sources

- Kent, James A. Riegel's Handbook of Industrial Chemistry (Eighth Edition) Van Nostrand Reinhold Company (1983) ISBN 0-442-20164-8

References

- Record in the GESTIS Substance Database of the Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

- "Turpentine". European Chemicals Agency.

- Mayer, Ralph (1991). The Artist's Handbook of Materials and Techniques (Fifth ed.). New York: Viking. p. 404. ISBN 0-670-83701-6.

- Kent p.569

- Barnhart, R. K. (1995). The Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-270084-7.

- Dieter Stoye "Solvents" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2002, Wiley-VCH, Wienheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a24_437

- Kent p.571

- Prizer, Tom (June 11, 2010). "Catfaces: Totems of Georgia's Turpentiners | Daily Yonder | Keep It Rural". dailyyonder.com. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- Kent pp.571&572

- Stenius, Per, ed. (2000). "2". Forest Products Chemistry. Papermaking Science and Technology. 3. Finland. pp. 73–76. ISBN 952-5216-03-9.

- Kent p.572

- "Surviving 'The Spanish Lady' (Spanish flu), 06:09, Residents of a small Alberta town recall their deadly brush with 1918's Spanish flu". CBC Digital Archives. 2003-04-10. Event occurs at 03:20. Lay summary.

A turpentine and hot water, and [wring hot towels out of there], and put it on their chest and back. --Elsie Miller (nee Smith)

- Laurence Bergreen (2003). "Over the edge of the world : Magellan's terrifying circumnavigation of the globe". ISBN 0066211735. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- "Home Remedies - American Memory Timeline- Classroom Presentation". American Memory Timeline. The Library of Congress. Retrieved 2017-02-06.

- "ICSC 1063 - TURPENTINE". www.inchem.org.

- "Turpentine enema". Biology-Online Dictionary. Biology-Online. Retrieved 2019-12-26.

- "Ribbons and Rituals". In Problems in Modern Latin American History. Ed. Chasteen and Wood. Oxford, UK: Scholarly Resources, 2005. p. 97

- Charles H. Haswell. "Reminiscences of New York By an Octogenarian (1816 - 1860)".

- "The "Whale Oil Myth"". PBS NewsHour. 20 August 2008.

- "Honda History". Smokeriders.com.

- "If Only They Could Talk". Retrieved 28 June 2018 – via www.amazon.co.uk., summarised at "James Herriot Books". Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- Rohrer, Finlo (28 July 2014). "When gin was full of sulphuric acid and turpentine". Retrieved 2 January 2018 – via www.bbc.com.

- "CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards - Turpentine - Symptoms". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- "Turpentine". International Programme on Chemical Safety, World Health Organization.

- "CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards - Turpentine". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Turpentine. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1879 American Cyclopædia article Turpentine. |

| Wikisource has the text of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (9th ed.) article Turpentine. |

- Inchem.org, IPCS INCHEM Turpentine classification, hazard, and property table.

- CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards - Turpentine

- FAO.org, Gum naval stores: Turpentine and rosin from pine resin

- FloridaMemory.com, Florida State Archive photographs of turpentine camps and laborers

- HCHSonline.org, Timber and Turpentine Industries

- Distil my beating heart

- Florida's "Turpmtine" Camps

- Turpentine Industry at A History of Central Florida Podcast