Teresa Carreño

María Teresa Gertrudis de Jesús Carreño García (December 22, 1853 – June 12, 1917) was a Venezuelan pianist, soprano, composer, and conductor.[1] Over the course of her 54-year concert career, she became an internationally renowned virtuoso pianist and was often referred to as the "Valkyrie of the Piano".[2] Carreño was an early adopter of the works of one of her students and friend, American composer and pianist Edward MacDowell (1860–1908) and premiered several of his compositions across the globe. She also frequently performed the works of Norwegian composer and pianist Edvard Grieg (1843–1907).[3] Carreño composed approximately 75 works for solo piano, voice and piano, choir and orchestra, and instrumental ensemble. Several composers dedicated their compositions to Carreño, including Amy Beach (Piano Concerto in C-sharp minor) and Edward MacDowell (Piano Concerto No. 2).

Teresa Carreño | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | María Teresa Gertrudis de Jesús Carreño García December 22, 1853 Caracas, Venezuela |

| Died | June 12, 1917 (aged 63) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation | Pianist, soprano, composer, and conductor |

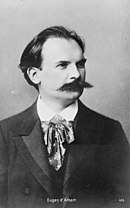

| Spouse(s) | Émile Sauret (m. 1873–1877), Giovanni Tagliapietra (dom. part. 1877–1889), Eugen d'Albert (m. 1892–1895), Arturo Tagliapietra (m. 1902–1917) |

| Children | Emilita (1874–1978), Luisa (1878–1881), Teresita (1882–1951), Giovanni (1885–1965), Eugenia (1892–1950), Hertha (1894–1974) |

Early life and education

María Teresa Carreño García de Sena was born in Caracas, Venezuela, on December 22, 1853, to Manuel Antonio Carreño (1812–1874) and Clorinda García de Sena y Rodríguez del Toro (1816–1866). Her father was the son of José Cayetano Carreño (1773–1836) and came from a musical family. He gave her music lessons from an early age and oversaw her career until his death in 1874. Her mother was a cousin of Maria Teresa Rodriguez del Toro y Alayza, wife of South America's founding father Simón Bolívar, on whose honor she was named. Before leaving Caracas she also studied with a German musician, Julio Hohene.[4]

Career

In 1862 her family emigrated to New York City and Carreño entered the musical world with a series of private and public concerts.[5] During the first few weeks in New York City, she met American pianist and composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk, who heard her perform and promoted her as an artist.[6] At the age of eight on November 25 she made her debut at Irving Hall performing a Rondo Brillant, Op. 98 (Johann Nepomuk Hummel), accompanied by a quintet (Mosenthal, Matzka, Bergner, C. Preusser); Grande Fantaisie sur Moise, Op. 33 (Sigismond Thalberg); Nocturne (Theodor Döhler), Jerusalem (Louis Moreau Gottschalk); and Variations on "Home! Sweet Home!" Op. 72 (Thalberg) for an encore.[7] This debut was followed by concerts (1863–1865) across the northeastern and mid-Atlantic United States, including stops in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Washington, D.C.[8] During the fall of 1863 Carreño performed for Abraham Lincoln at the White House.[9] Interspersed with her North American concerts were concert performances in Cuba during the spring of 1863 and fall of 1865.[10]

In the spring of 1866, Carreño and her family left the United States for Paris, France, where she made her debut on May 14 at the Salle Érard.[11] During her time in Paris, she met many prominent musicians, including Gioachino Rossini, Georges Mathias (a pupil of Frédéric Chopin who may have given her a few lessons), Charles Gounod, and Franz Liszt.[12][13] Between 1866 and 1872, Carreño performed regularly in concerts across cities in the United Kingdom, France, and Spain. While in Paris, she studied voice with Rossini and later, during the 1870s, with Signor Fontana and Russian soprano Herminia Rudersdorff (1822–1882). Her preparation enabled her to step into the role of and appeared as the Queen in Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots during a performance with the Colonel Henry Mapleson troupe in Edinburgh, Scotland, after the leading lady, Thérèse Tiejens (1831–1877), became ill.[14] In New York, on February 25, 1876, she again performed in an operatic role, this time as Zerlina in Mozart's Don Giovanni.[15]

In 1872, she returned to the United States with an artist troupe (led by Max Strakosch) consisting of well-known musicians, including American singer Annie Louise Cary, operatic soprano Carlotta Patti, French violinist and composer Émile Sauret, baritone Signor Del Puente, and Italian tenor Giovanni Matteo de Candia, who went by the stage name of Mario. During 1873/1874 she appeared in performances in England with the Philharmonic Society,[16] and in M. Riviere's promenade concerts,[17] London Ballad Concerts,[18][19] Hanover Square Rooms,[20] and the Monday Popular Concerts.[21] While touring with the Max Strakosch troupe, Carreño and Sauret became romantically involved and on July 13, 1873, they were married in London, England. They had one child, Emilita (b. March 23, 1874), who was left in the care of a family friend, Mrs. James Bischoff, while Carreño and Sauret pursued musical opportunities in the United States. Emilita was eventually adopted by the Bischoff family.

Between 1876 and 1889, Carreño resided and toured primarily in the United States, sharing concert bills with famous operatic singers, including Adelina Patti, Emma Abbott, Clara Louise Kellogg, Emma C. Thursby, and Ilma De Murska, and musicians, including violinist August Wilhelmj[22] and Giovanni Tagliapietra.[23] After Carreño's marriage to Sauret dissolved, she became involved with Tagliapietra and entered into a common-law marriage. They had three children: Louisa (March 1, 1878 – May 16, 1881), Teresita (December 24, 1882 – 1951), and Giovanni (January 8, 1885 – 1965). Following in their mother's footsteps, Teresita pursued a career as a concert pianist, and Giovanni as an opera singer. During these years she appeared with the Theodore Thomas Orchestra and Damrosch Orchestra. Although Carreño often appeared as a supporting artist during the 1870s into the early 1880s, she on occasion performed solo piano concerti, including Mendelssohn's Piano Concerto no. 1,[24] and Grieg's Piano Concerto, Op. 16.[25] By 1883 Carreño began promoting and performing the works of Edward MacDowell in the United States and later abroad. Some of the most frequently performed works include his First Modern Suite, Op. 10, Serenade, Op. 16, Second Modern Suite, Op. 14,[26] "Erzählung" and "Hexentanz" from 2 Fantasiestücke, Op. 17; Étude de concert, Op. 36; Piano Concerto No. 1, Op. 15; Piano Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 23 (dedicated to her).

At the invitation of General Joaquín Crespo, the president of Venezuela, Carreño and Tagliapietra traveled to Caracas, Venezuela, arriving in October 1885, with the intention of establishing an opera company and plans for a music conservatory. Carreño gave several performances, including one on October 27 at Teatro Guzmán Blanco in Caracas, which included the performance of her composition, Himno a Bolívar, dedicated to Venezuela's founding father.[27][28] Carreño and Tagliapietra returned to Venezuela again in 1887 in order to open the season at Teatro Guzmán Blanco with their new opera company. Unfortunately their efforts did not pay off largely due to the political unrest, dissatisfied audiences, and abandoned musical posts.[29] They returned to New York in August 1887 and continued performing in the United States.

For several years, Carreño had planned to return to Europe and establish herself as a virtuoso pianist. On November 18, 1889, she debuted with the Berlin Philharmonic, conducted by Gustav F. Kogel at the Singakademie. On this occasion she performed Edvard Grieg's Piano Concerto, Schumann's Symphonic Studies, Op. 13, and Weber's Polonaise brillante (arr. Franz Liszt).[30] During the early years in the United States, Carreño's concerts were managed by several different individuals, however, as she established herself in Germany and abroad, she chose to work primarily through the Hermann Wolff Concert Bureau and became close friends with Hermann Wolff and his wife, Louise. Around 1890, Carreño became acquainted with Scottish-born German pianist and composer Eugen d'Albert, also managed by Wolff. Their musical friendship turned romantic and by late 1891 they moved into a home, which they named Villa Teresa in Coswig. They were married on July 27, 1892.[31] On September 27, 1892, their first child, Eugenia was born, followed by Hertha on September 26, 1894. During their marriage, the couple often appeared on the same concert bill and Carreño began performing works by d'Albert, including his Piano Concerto no. 2, Op. 12. D'Albert was a controlling individual in matters related to child rearing, household management, and even Carreño's repertoire choices, which resulted in the exclusion of MacDowell's music from her performances during their marriage.[32] Their marriage ended in divorce in 1895.[33][34] She would remarry again in June 1902 to Arturo Tagliapietra, the brother of her second husband. He had joined her in Berlin around 1897 and assisted her with her concert plans and accounts.

Following her success in Germany and other European states, Carreño returned to the United States in 1897 to an eager audience. Performing in Hartford, Connecticut, a critic for the Hartford Courant wrote: "Teresa Carreno the piano virtuoso, made her first appearance to-day at the Philharmonic Concert, Carnegie Hall, under the baton of Anton Seidl. Her magnificent technique displayed to the highest degree the marvelous sonority of the Knabe piano, upon which she played, and she received one of the greatest ovations of the season."[35] From this point forward in her career, Carreño appeared in concerts as a featured artist, solo or with orchestra. She performed under the baton of many prominent conductors, including Edvard Grieg, Gustav Mahler, Theodore Thomas, Wilhelm Gericke, Hans von Bülow, and Henry Wood. In his memoir, Henry Wood wrote that "It is difficult to express adequately what all musicians felt about this great woman who looked like a queen among pianists - and played like a goddess. The instant she walked onto the platform her steady dignity held her audience who watched with riveted attention while she arranged the long train she habitually wore. Her masculine vigour of tone and touch and her marvellous precision on executing octave passages carried everyone completely away."[36]

Among the most frequently performed composers in her repertoire were Chopin, Liszt, Tchaikovsky, Grieg, MacDowell, Schumann, Rubinstein, Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Weber, and occasionally her own. Carreño recorded over forty compositions for the reproducing piano between 1905 and 1908. These were released primarily by Welte-Mignon and reissued by other piano roll manufacturers. Her daughter Teresita also recorded for player piano in 1906 for Welte-Mignon. In addition to her performances, Carreño gave lessons to students in many of the cities she visited. In the early 1900s, her students traveled to her summer residence during the summer months to study with her for weeks at a time. Amongst her students were her early biographer Marta Milinowski, as well as Fanny Nicodé née Kinnel, Helen Wright,[37] and Julia Gibansky-Kasanoff.[38] For the remainder of her career, Carreño performed in cities across Europe (including Russia) with only a few concert seasons in North America during 1907–08, 1909–10, and 1916, as well as two visits to Australia and New Zealand in 1907/1908[39] and 1910/1911,[40] the latter which also included stops in South Africa.[41] Carreño and A. Tagliapietra returned to New York City in September 1916 for a 1916–1917 concert season with performances planned across the United States and Cuba. In 1916 she performed for President Woodrow Wilson at the White House. During her trip to Havana, Cuba in March 1917, however, she became ill and returned to New York where she was diagnosed with diplopia. Her health declined rapidly and she died on June 12, 1917, in her apartment in New York City at the age of 63.[42]

Compositions

Teresa Carreño composed approximately 75 works for piano, voice and piano, choir and orchestra, chamber music, and several merengues, incorporating the form as an interlude in some of her pieces (for example, in her piece entitled Un Bal en Rêve). Her earliest compositions (in manuscript) date back to ca. 1860.[43] One of her first pieces published the year after her debut in New York City was the "Gottschalk Waltz" (1863),[44] dedicated to Louis Moreau Gottschalk. The majority of her works were composed before 1875 and were published by various publishers in locations including Paris (Heugel, Brandus & S. Dufour), London (Duff & Stewart), Madrid (Antonio Romero), New York (G. Schirmer, Edward Schuberth), Boston (Oliver Ditson & Co.), Philadelphia (Theodore Presser), Cincinnati (The John Church Company), Leipzig (Fr. Kistner & C. F. W. Siegel) Sydney and Melbourne (Allan & Co.).

Only a handful of works were composed post-1880, including two works for chorus, Himno a Bolívar (ca. 1883) and Himno al ilustre americano (ca. 1886). The first piece was dedicated to General Joaquín Crespo and premiered during her visit to Caracas in 1885. The second piece was written in honor of Antonio Guzmán Blanco, president of Venezuela (1879–1884, 1886–1887). Her composition Kleiner Walzer (Mi Teresita) (ca. 1885) composed for her daughter Teresita was one of her most popular pieces during her lifetime and she often performed it as an encore at her own concerts. During her Berlin residency in the 1890s, Carreño composed two chamber works, Serenade for String Orchestra (ca. 1895) and String Quartet in B-minor (1896). The latter which was performed by the Klinger Quartet in the Leipzig Gewandhaus in 1896.[45]

Legacy

In 1938 Carreño's ashes were repatriated to Caracas, Venezuela. They were later exhumed and interred at the Panteón Nacional in 1977.

Vassar College acquired Teresa Carreño's papers in the early 1930s and officially purchased them in 1941. In 1957 a portion of the (un-inventoried) collection was dispersed between Vassar and the National Library in Caracas, Venezuela.[46] These materials are now housed in the Centro Documental Teatro Teresa Carreño. A finding aid is available for the extant Teresa Carreño Papers at Vassar College in the Archives & Special Collections Library.

The Teresa Carreño Cultural Complex in Caracas is named in honor of Carreño.[47] The center serves as the residence for the Venezuela Symphony Orchestra. The complex also houses the Centro Documental Teatro Teresa Carreño and the Sala de Exposición Teresa Carreño. The Centro Documental serves as the main archive for Carreño in Venezuela. It houses primary source materials, including correspondence, legal documents, concert programs, scores, reviews, photographs, and other personal items. The Sala de Exposición exhibits materials once owned by Carreño, including her concert dresses, Weber piano (recovered through the efforts of Venezuelan pianist Rosario Marciano), and other personal items.[48] There is also a crater on Venus named after Carreño.

As of June 1, 2015 Andreina Gómez began directing a feature film, Teresita y El Piano, about the life of Teresa Carreño.[49]

In 2018, a Google Doodle was created to celebrate her 165th Birthday.[50]

Notes

- "Mme. Teresa Carreno, Famous Pianist, Dies. Artist, Who Also Had a Career in Opera, a Victim of Paralysis at 63" (PDF). The New York Times. June 13, 1917. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

Teresa Carreno most famous of women pianists, died last night at 7 o'clock in her home, 740 West End Avenue, after an illness of several months, which finally developed into paralysis. She was 63 years old, and was once the teacher of Edward MacDowell. ...

- "Teresa Carreno's Death Ends a Notable Career". Musical America: 13–14. June 23, 1917.

- Kijas, Anna (2013). ""A suitable soloist for my piano concerto": Teresa Carreño as a promoter of Edvard Grieg's music". Notes: Quarterly Journal of the Music Library Association. 70 (1): 37–58. doi:10.1353/not.2013.0121.

- "n/a". La crónica. March 12, 1863.

- "Musical Phenomenon". New York Herald. October 27, 1862.

- "Teresa Carreno". La Musica Ilustrada Hispano-Americana. 1901. Retrieved July 12, 2015.; accessed via RIPM(subscription required).

- "Debut at Irving Hall (November 25, 1862)". Documenting Carreño. November 25, 1862.

- Kijas, Anna (2016). "Teresa Carreño: 'Such gifts are of God and should not be prostituted for mere gain'". In McPherson, Gary (ed.). Musical Prodigies: Interpretations from Psychology, Music Education, Musicology and Ethnomusicology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199685851.

- Music in Lincoln's White House - White House Historical Association

- Kijas, Anna. "Concerts in Cuba". Documenting Carreño.

- "n/a". L'Art Musical: 190. May 17, 1866.

- Acteon (June 20, 1866). "unknown". La época.

- "A New Pianist". Orchestra: 203. June 23, 1866.

- "n/a". Orchestra: 392. March 22, 1872.

- "n/a". Dwight's Journal of Music: 199. March 18, 1876.

- "n/a". The Athenaeum: 831. June 28, 1873.

- "n/a". The Orchestra: 297. August 8, 1873.

- http://admin.concertprogrammes.org.uk/html/search/verb/GetRecord/2790

- "n/a". The Athenaeum: 705. November 29, 1873.

- "n/a". The Athenaeum: 836. June 20, 1874.

- "n/a". The Musical Standard: 145. March 7, 1874.

- "n/a". The New York Times. October 10, 1878.

- "n/a". New York Times. February 25, 1876.

- "n/a". New York Herald. November 24, 1877.

- "n/a". Hartford Daily Courant. March 17, 1883.

- Note: First performance of this work in Chicago. (March 9, 1884). "n/a". Chicago Daily Tribune.

- Milanca Guzmán, Mario (1987). "Dislates en la obra Teresa Carreño, de Marta Milinowski". Revista de música latinoamericana. 8 (2): 198–99.

- "n/a". El siglo. October 29, 1885.

- "n/a". Le Ménestrel: 214. June 5, 1887.

- "n/a". Neue Berliner Musikzeitung. 43 (48). November 28, 1889.

- "n/a". San Francisco Call. 71 (145). April 24, 1892.

- Letter from Frances MacDowell to Carreño, May 24, 1896. Series 3: Correspondence, folder 8.11. Teresa Carreño Papers, Archives and Special Collections Library, Vassar College Libraries.

- "n/a". New York Times. October 6, 1895.

- Divorce papers, Series 6: Legal Documents, folder 14.1. Teresa Carreño Papers, Archives and Special Collections Library, Vassar College Libraries.

- "n/a". Hartford Courant. January 9, 1897.

- Wood, Sir Henry Joseph (1938). My life of music. London: V. Gollancz. pp. 147–148.

- The Helen Wright Papers, MSS 2

- Julia Gibansky Kasanoff papers relating to Teresa Carreño, 1902-1937

- "n/a". The Examiner. April 22, 1907 – via Trove.

- "n/a". Otago Daily Times. June 16, 1910.

- "Echoes of Music Abroad". Musical America: 11. January 21, 1911.

- "Mme. Teresa Carreno, Famous Pianist, Dies. Artist, Who Also Had a Career in Opera, a Victim of Paralysis at 63" (PDF). The New York Times. June 13, 1917. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

Teresa Carreno most famous of women pianists, died last night at 7 o'clock in her home, 740 West End Avenue, after an illness of several months, which finally developed into paralysis. She was 63 years old, and was once the teacher of Edward MacDowell.

- "Teresa Carreño Papers, Archives and Special Collections Library, Vassar College Libraries".

- 104.044 - Gottschalk Waltz. | Levy Music Collection

- "n/a". The Musical Times: 335. May 1, 1896.

- Patkus, Ronald D. "MUSICAL MIGRATIONS: A CASE STUDY OF THE TERESA CARREÑO PAPERS". RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage. 6: 26–33. doi:10.5860/rbm.6.1.239.

- Jean-Pierre Thiollet, 88 notes pour piano solo, "Solo nec plus ultra", Neva Editions, 2015, p.51. ISBN 978 2 3505 5192 0.

- Marciano, Rosario (1975). Protocolo y resurrección de un piano. Caracas, Venezuela: Ministerio de Educación, Dirección de Apoyo Docente, Departamento de Publicaciones.

- "TERESITA & THE PIANO". Cinando. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- "Teresa Carreño's 165th Birthday". www.google.com. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

Bibliography

- Albuquerque, Anne E. (1988). Teresa Carreño: Pianist, Teacher, and Composer. DMA thesis, University of Cincinnati.

- Bomberger, E. Douglas (2013). MacDowell. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Clemente Travieso, Carmen (1953). Teresa Carreño (1853–1917): Ensayo biográfico. [Caracas]: Agrupación Cultural Femenina.

- Eloy Gutiérrez, Jesús (2013; 2017). Para conocer a Teresa Carreño. Caracas: Centro Documental del TTC.

- ______ (2019). Teresa Carreño: Cartas y documentos: Compilación documental (1863-1917). La Campana Sumergida.

- Kijas, Anna E. (2013). ""A suitable soloist for my piano concerto": Teresa Carreño as a promoter of Edvard Grieg's music". Notes: Quarterly Journal of the Music Library Association. Music Library Association. 70 (1): 37–58. doi:10.1353/not.2013.0121.

- ______ (2016). "Teresa Carreño: 'Such Gifts Are of God, and Ought Not to Be Prostituted for Mere Gain.'" In Musical Prodigies: Interpretations from Psychology, Music Education, Musicology and Ethnomusicology, edited by Gary McPherson, 621–37. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ______ (2019). The Life and Music of Teresa Carreño (1853-1917): A Guide to Research. Middleton: A-R Editions.

- Lawrence, Vera Brodsky, and George T. Strong (1999). Repercussions, 1857–1862. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Mann, Brian (1991). "The Carreño Collection at Vassar College." Notes: Quarterly Journal of the Music Library Association. Music Library Association. 47 (4):1064–83. doi:10.2307/941613.

- Marciano, Rosario (1966). "Teresa Carreño, o un ensayo sobre su personalidad: A los 50 años de su muerte". Coleccion musica, 2. Caracas: Instituto Nacional de Cultura y Bellas Artes.

- ______ (1971). "Teresa Carreño: Compositora y pedagoga". Colección Donaire. Caracas: Monte Avila Editores.

- ______ (1975). "Protocolo y resurrección de un piano". Caracas: Ministerio de Educación, Dirección de Apoyo Docente, Departamento de Publicaciones.

- Milanca Guzmán, Mario (1987). "Dislates en la obra Teresa Carreño, de Marta Milinowski." Revista de música latinoamericana 8 (2):185–215.

- ______(1996). "Teresa Carreño: Manuscritos inéditos y un proyecto para la creación de un Conservatorio de Música y Declamación." Revista musical chilena 50, (186): 13–39.

- Milinowski, Marta (1940). Teresa Carreño: 'By the Grace of God.' New Haven: Yale University Press; London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press.

- Pangels, Charlotte (1981). Eugen d'Albert: Wunderpianist und Komponist; Eine Biographie. Zürich: Atlantis Musikbuch-Verlag.

- Peña, Israel (1953). Teresa Carreño (1853–1917). Biblioteca Escolar, Colección de Biografias, no. 11. Caracas: Fundaciâon Eugenio Mendoza.

- Peñín, José (1993). "21 cartas de Teresa Carreño a Guzmán Blanco." Revista musical de Venezuela 14, (32–33): 25–57.

- Pita, Laura (2015). Carreño, (María) Teresa. Grove Music Online. (2015-05-28).

- Pita Parra, Laura Marina (1999). Presencia de la obra de Edward MacDowell en el repertorio de Teresa Carreño: Revisión de programas de concierto, correspondencia, reseñas de prensa y otros documentos pertenecientes al Archivo Histórico de Teresa Carreño en Caracas. Licentiate thesis, Universidad Central de Venezuela.

- Stevenson, Robert Murrell (1983). "Carreño's 1875 California Appearances." Inter-American Music Review 5, (2): 9–15.

- Thompson, Barbara Tilden (2001). The Twentieth-Century United States Concert Tours of Teresa Carreño. Master's thesis, Temple University.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Teresa Carreño. |