Temple of Proserpina

The Temple of Proserpina[1] or Temple of Proserpine[2] (Maltese: Tempju ta' Proserpina) was a Roman temple in Mtarfa, Malta, an area which was originally a suburb outside the walls of Melite. It was dedicated to Proserpina, goddess of the underworld and renewal.

| Temple of Proserpina | |

|---|---|

Tempju ta' Proserpina | |

| |

| General information | |

| Status | Destroyed |

| Type | Temple |

| Architectural style | Ancient Roman |

| Location | Mtarfa, Malta |

| Coordinates | 35°53′29.6″N 14°24′4.6″E |

| Construction started | Unknown |

| Renovated | 1st century BC or AD |

| Destroyed | Unknown, ruins cleared 17th–18th centuries |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Marble |

The date of construction is unknown, but it was renovated in the 1st century BC or AD. The ruins of the temple were discovered in 1613, and most of its marble blocks were later used in the decoration of buildings, including Auberge d'Italie and the Castellania in Valletta.[3] Only a few fragments still survive today.

History and architecture

The only epigraphic evidence of the temple is the Chrestion inscription, which was discovered among its ruins in 1613.[4] It records that the temple was already old and was threatening to collapse during the reign of Augustus in the 1st century BC or AD,[5] and it was restored by Chrestion, the procurator of the Maltese Islands.[6] This inscription is the earliest known Latin text that was found in Malta.[7] It read:

CHRESTION AVG. L PROC

(meaning Chrestion, a freedman of Augustus, Procurator of the islands of Melite and Gaulos, repaired the columns together with the roof and walls of the temple of the goddess Proserpina, that through age were ready to tumble down, he likewise gilded the pillar.)[8]

INSVLARVM MELIT. ET GAVL

COLVMNAS CVM FASTIDIIS

ET PARIETIBVS TEMPLI DEÆ

PROSERPINÆ VETVSTATE

RVINAM IMMINIENTIBVS

................... RES

TITVIT SIMVL ET PILAM

INAVRAVIT.

The temple was built out of marble and its columns were in the Corinthian order.[9] If still in use by the 4th-century, the temple would have been closed during the persecution of pagans in the late Roman Empire.

Discovery of remains and destruction

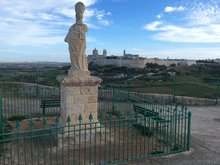

A chapel dedicated to Saint Nicholas was eventually built near the site of the temple.[11] In 1613, while digging the foundations for a statue of that saint near the chapel, many large blocks of marble from the temple were found, together with pillars, cornices, capitals and carved slabs including the Chrestion inscription. The chapel no longer exists, but the statue of St. Nicholas still stands on the site of the temple.[9][12]

The discovery of the temple was recorded by Giovanni Francesco Abela in his 1647 book Della Descrizione di Malta Isola nel Mare Siciliano con le sue Antichità, ed Altre Notizie.[13][14]

Over the following centuries, most of the remains of the temple were used in the construction of new buildings. In the 1680s, some marble blocks were used to carve the trophy of Gregorio Carafa above the main entrance of Auberge d'Italie in Valletta.[15][16] The façade of the Castellania, which was built in the late 1750s, also contains marble cannibalized from the Temple of Proserpina.[9]

The temple was a very frequented site by almost all archeologist on the islands in the 19th century.[17] In A hand book, or guide, for strangers visiting Malta, written by Thomas MacGill in 1839, it is mentioned that "not a vestige of [the temple] remains above ground", but some fragments were found at the Public Library in Valletta.[18]

The archaeologist Antonio Annetto Caruana examined the site of the temple in 1882, and found no remains except for some holes dug in the rock. He recorded that some capitals, pillars and cornices were piled up in the square in front of the Mdina cathedral, while other remains were found in the private collection of Mr. Sant Fournier.[9]

Today, only a few fragments from the temple still exist. These include a fluted marble column shaft and part of a cornice.[19] Only a few broken fragments of the original Chrestion inscription have survived.[20]

See also

Further reading

- Dingli, Pauline (2009). Discover Rabat: Mdina and Exceptional Outskirts. 2. Self-Published supported by the Malta Tourism Authority. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-99932-063-2-3.

- Mercieca, Simon (2014). "The Proserpina Temple and the History of its Chrestion Inscription" (PDF). Treasures of Malta, 61. 21 (1): 32–39. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2019.

- Criticism by Gio Anton Vassallo

References

- "Anna and Malta". maltahistory.eu5.net.

- Some theories suggest that the temple was a Greek Temple dedicated to Persephone, the Greek equivalent to the Roman Goddess Proserpina. Two theories are that: the temple was located outside Melite (a Roman city) as it was Greek not Roman; and that close by in Mtarfa there was the Temple of Zeus. Persephone was the daughter of Zeus. However the restoration marble refers to the temple as of Proserpina not Persephone. in Cult and continuity.

- Bonanno, Anthony (2016). "The Cult of Hercules in Roman Malta: a discussion of the evidence". In Victor Bonnici (ed.). Melita Classica (PDF). 3. Journal of the Malta Classics Association. pp. 243–264. ISBN 978-99957-847-4-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 April 2019.

- "Newspaper article" (PDF). www.um.edu.mt. 1999. Retrieved 2020-03-20.

- Sagona 2015, p. 285

- Cardona 2008–2009, pp. 40–41

- Bonanno & Militello 2008, p. 237

- Bryant 1767, p. 53

- Caruana 1882, pp. 142–143

- "NICPMI 2318".

- "History of a little rural chapel" (PDF). melitensiawth.com. Retrieved 2020-03-20.

- Scerri, John. "Mtarfa". malta-canada.com. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016.

- Cardona 2008–2009, p. 42

- Abela, Giovanni Francesco (1647). Della Descrizione di Malta Isola nel Mare Siciliano con le sue Antichità, ed Altre Notizie (in Italian). Paolo Bonacota. p. 207.

- MacGill 1839, pp. 62–63

- Guillaumier, Alfie (2005). Bliet u Rħula Maltin. Klabb Kotba Maltin. p. 922. ISBN 99932-39-40-2.

- The historical guide to the island of Malta and its dependencies. p. 68-69.

- MacGill 1839, pp. 104–105

- Cardona 2008–2009, p. 47

- Busuttil, Joseph (2015). "The Chrestion Inscription". Treasures of Malta (62): 60–63.

Bibliography

- Bonanno, Anthony; Militello, Pietro, eds. (2008). Malta in the Hybleans, the Hybleans in Malta. Palermo: Officina di Studi Medievali. ISBN 9788888615752.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bryant, Jacob (1767). Observations and inquiries relating to various parts of ancient history. University of Cambridge. p. 53.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cardona, David (2008–2009). "The known unknown: identification, provenancing, and relocation of pieces of decorative architecture from Roman public buildings and other private structures in Malta" (PDF). Malta Archeological Review. Midsea Books (9): 43. ISSN 2224-8722. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Caruana, Antonio Annetto (1882). Report on the Phoenician and Roman antiquities in the group of the islands of Malta. Malta: Government Printing Office.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacGill, Thomas (1839). A hand book, or guide, for strangers visiting Malta. Malta: Luigi Tonna.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sagona, Claudia (2015). The Archaeology of Malta. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107006690.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)