Tectonic evolution of the Aravalli Mountains

The Aravalli Mountain Range is a northeast-southwest trending orogenic belt in the northwest part of India and is part of the Indian Shield that was formed from a series of cratonic collisions.[1] The Aravalli Mountains consist of the Aravalli and Delhi fold belts, and are collectively known as the Aravalli-Delhi orogenic belt. The whole mountain range is about 700 km long.[2] Unlike the much younger Himalayan section nearby, the Aravalli Mountains are much older that can be traced back to the Proterozoic Eon. The collision between the Bundelkhand craton and the Marwar craton is believed to be the primary mechanism for the development of the mountain range.[1]

The precise evolutionary processes responsible for the Aravalli Mountain Range remains controversial today, with diverse theories put forward for the tectonic history.

Geology of the Aravalli Mountains

The Aravalli Mountain Range features horst-like structure and consists of a series of Proterozoic rocks that are intensely deformed and metamorphosed.[3]

General formation

Three main subdivisions of rocks constitute the stratigraphy of the mountain range, with the Archean Bhilwara Gneissic Complex basement being the lowest strata, followed by the overlying lower Aravalli Supergroup and the upper Delhi Supergroup.[2] The northern part of the mountain range only consists of the Delhi Supergroup, and this has given to its name of ‘North Delhi Belt.[2] On the southern side, however, both the Aravalli and Delhi supergroups are present. The mountain range is bounded by the Eastern and Western marginal faults, where the former is also termed as the Great Boundary Fault.[3]

| General geological formation of the Aravalli Mountains | ||

|---|---|---|

| Delhi Supergroup | Ajabgarh Group (=Kumbhalgarh Group) | Carbonate, mafic volcanic and argillaceous rocks |

| Alwar Group (= Gogunda Group) | Arenaceous and mafic volcanic rocks | |

| Raialo Group | Mafic volcanic and calcareous rocks | |

| Aravalli Supergroup | Jharol Group | Turbidite facies and argillaceous rocks |

| Debari Group | Carbonates, quartzite, and pelitic rocks | |

| Delwara Ggroup | ||

| Archean basement | Banded Gneissic Complex (BGC) | Schists, gneisses and composite gneiss

Quartzites |

Archean Bhilwara Gneissic Complex basement

The Bhilwara Gneissic Complex basement is about 2.5 Ga old.[2] It is made up of a group of metamorphic and igneous rocks that are mainly amphibolite to granulite grade, tonalitic to granodioritic gneisses and intrusive granitoids with a minor amount of metasedimentary and metavolcanic rocks.[4][5] The basement is categorized into two subdivisions: the Sandmata Complex and the Mangalwar Complex.[6][7] The Sandmata Complex refers to gneisses and granitoids while the Mangalwar Complex refers to the metasedimentary and metavolcanic series which are considered to be metamorphosed older granite-greenstone belt.[6][7]

Aravalli Supergroup

On top of the Archean basement, the Aravalli Supergroup overlies with clear unconformities separating the two strata.[3] The Aravalli Supergroup is divided into three groups: lower Delwara Group, middle Debari Group, and Upper Jharol Group.[8] The lower and middle groups shared similar lithology, where both groups are dominated by carbonates, quartzite, and pelitic rocks, thus suggesting a shelf depositional environment. Turbidite facies and argillaceous rocks are prominent in the upper Jharol group, thus suggesting a deep marine depositional environment.[8] The depositional age of these sequences ranges approximately from 2.1 to 1.9 Ga.[2]

Three major episodes of deformation and metamorphism were involved in the Aravalli Supergroup, including foldings, shearing, kink bands and crenulations etc.[8] Metamorphic grades of the rocks generally range from greenschist facies to amphibolite facies.[8]

Delhi Supergroup

The upper Delhi Supergroup overlies on the Aravalli Supergroup with a clear unconformity.[3] This supergroup hosts two main types of rocks: a thick sequence of volcanic rocks that is of continental affinity; and sedimentary rocks that represent fluvial and shallow marine environments and deep marine depositional environment.[3] The depositional age of these sequences is approximately from 1.7 to 1.5 Ga.[2]

In the ‘North Delhi belt’, the Delhi Supergroup is classified into three groups: lower Raialo Group, middle Alwar Group, and upper Ajabgarh Group.[4][9] The Raialo Group consists predominantly of mafic volcanic and calcareous rocks.[2] The Alwar Group mainly consists of arenaceous and mafic volcanic rocks.[2] The Ajabgarh Group is dominated by carbonate, mafic volcanic and argillaceous rocks.[2] In the southern part, similar rock types, despite different names, are identified, where they are Gogunda Group (equivalent to Alwar group) and the Kumbhalgarh Group (equivalent to Ajabgarh Group).[4][10]

Four phases of tectonic evolution

The tectonic evolution of the Aravalli-Delhi orogenic belt can be divided into four phases:[6]

- Bhilwara Gneissic Complex (~ 2,500 Ma)

- Aravalli Orogeny (~ 1,800 Ma)

- Delhi Orogeny (~ 1,100 Ma)

- Post-orogenic evolution (~ 850 – 750 Ma)

Two phases of rifting, sedimentation, collision and suturing were documented in the tectonic evolution of the Aravalli-Delhi orogenic belt.[6] During Proterozoic Eon, N-S convergence between the Bundelkhand and Bhandara cratons at the Satpura Mobile Belt, and E-W convergence between the Bundelkhand and Marwar cratons at the Aravalli-Delhi orogenic belt have synchronously occurred in India.[1] This resulted in an overall resultant force of NE-SW convergence of the Aravalli-Delhi orogenic belt, and also led to the arcuate shape of its convergent zone.[1]

Evolution of the Archean basement

The Aravalli Mountains basement started with an older sialic crust evolving into extensive granitic batholiths by the emplacement of granitic bodies during the period ca. 3.0 to 2.5 Ga.[3] This subsequently led to rapid cratonization and rapid thickening of crust to about 20–25 km.[11][12] The main crustal source is believed to be old crustal components of the area.[4][13] The region subsequently experienced a large scale metamorphic event that granite is partly metamorphosed into gneissic rocks, forming the Archean Basement.[3] These cratonization processes continued together signifying the end of amalgamation of cratonic nuclei that constitutes the development of an early continental crust.

Aravalli Orogeny

During the Paleoproterozoic Era, the opening of Aravalli oceanic basin separated the eastern Bundelkhand craton and the western Marwar craton.[6] Sedimentation of the Aravalli Supergroup took place simultaneously with basic magmatism and followed by a gradual subsidence of the Aravalli Basin floor.[3][14]

Soon after the rifting phase ended, the compressional phase took place where the eastern Bundelkhand craton subducted under the western Marwar craton.[6] As collision continued, the subduction zone steepened, leading to the development of an island arc between the two cratons.[6] After collision had proceeded for a certain period of time, the uplift of the Aravalli Supergroup was induced at around 1800 Ma.[2][6] In the last stage of convergence, the thrust fault further steepened and the colliding blocks eventually become sutured.[6] The suture zone is marked by the Great Boundary Fault.[8]

Delhi Orogeny

During the Mesoproterozoic Era, another rifting phase began.[6][15] At that time, the Bundelkhand-Aravalli-BGC and the Marwar craton lie on the eastern side and western side respectively as the rifting phase separated the Bhilwara Gneissic Complex (BGC) from the Marwar craton.[6] The oceanic basin created in the course of rifting received the Delhi Supergroup sediments.

The compressional phase that followed led to eastward subduction of the western Marwar craton.[6] Continuous subduction of the western block might have created another island arc, and similar to the Aravalli orogeny, further collision between the two blocks with island arc in between gave rise to the development of the Delhi orogeny around 1100 Ma.[4][6] The suture zone between the two cratons is marked by the Western Marginal Fault and the emplacement of the Phulad Ophiolite Suite in the region.[8]

Post-orogenic evolution

Acid magmatic events

The epilogue of the tectonic evolution was marked by granitic and rhyolitic magmatic events, namely the emplacement of the Erinpura granite and the Malani Volcanics on the western side of Aravalli-Delhi orogenic belt.[3] This event is ranked third among the largest igneous province in the globe, with a total area of about 52,000 km2 in India.[8] Malani Igneous Suite is a collective term for bimodal volcanic and plutonic rocks aged 873–800 Ma in the area.[8] The lithologies of the rock suite are predominantly rhyolitic and rhyodacitic volcanic rocks with granitoid intrusions overlying unconformably or intruding through the Delhi Supergroup.[5][8]

Purana basins formation

Apart from the vigorous post-orogenic magmatic event, a large number of so-called ‘Purana’ basins was actively developing near the orogenic belts.[8] The word ‘Purana’ means ‘ancient’ and was used to depict the group of isolated sedimentary basins with thick Proterozoic sedimentary strata that are relatively undeformed on the Indian Shield.[2] The Vindhyan Basin and the Marwar Basin are part of the Purana basins that sit near the Aravalli Mountain Range.

- Vindhyan Basin

The Vindhyan Basin is located on the southeastern side of the Aravalli Mountain Range where its formation is believed to be associated to the large downwarp of the crust after Delhi Orogeny.[8] It spans an area of about 104,000 km2 in the northwestern part of India overlying on the Archean Bhilwara Gneissic Basement.[16] The Vindhyan Supergroup is classified into two fundamental strata, lower and upper Vindhyan, with a large unconformity representing 500 million years interval between the strata.[2] Within each stratum, it is further categorized into major groups. The lower Vinhydan comprises the Semri Group while the upper Vinhyan consists of the Kaimur Group, Rewa Group, and Bhander Group.[2] The earliest sedimentation forming the lower Vindhyan can be traced back to Paleoproterozoic and stopped somewhere around early Mesoproterozoic (~1,721 Ma to 1,600 Ma).[16] Sedimentation forming the upper Vindhyan resumed again in the Mesoproterozoic and ceased in Neoproterozoic.[16][17] Vindhyan Supergroup portrayed transitional to shallow marine depositional environment, such as alluvial fan, delta, tidal flat, carbonate ramp etc.[16]

- Marwar basin

To the west of the Aravalli Mountain Range and far beyond the Vindhyan Basin lies the Neoproterozoic-to-Cambrian-aged Marwar Basin.[8] The Marwar Basin sits on the Malani Igneous Suite and contains a sedimentary section of 2 km in thickness.[8] Similar to other Purana basins, the Marwar Supergroup is less deformed and unmetamorphosed. The Marwar Supergroup is classified into three major groups: the lower Jodhpur Group, the middle Bilara Group, and the upper Nagaur Group.[8] Arenaceous rocks, calcareous rocks and evaporites are the dominant rock type in the Marwar Basin.[8]

Association with supercontinent cycles

The tectonic events and basin developmental phases are thought to be correlated to the amalgamation and breakup of plates during supercontinent cycles of Columbia, Rodinia, and Gondwana.

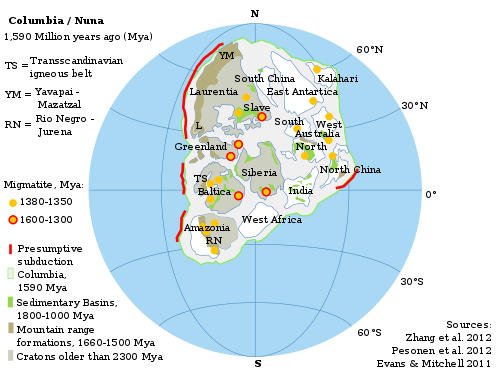

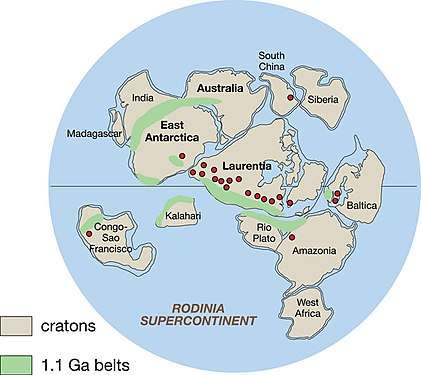

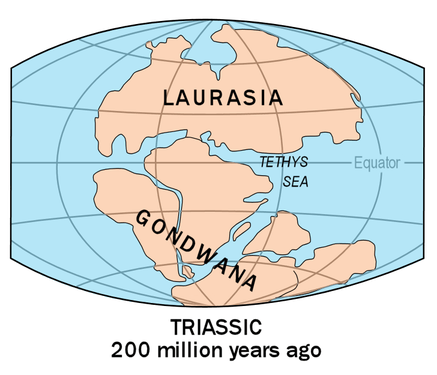

The Aravalli orogeny (~1,800 Ma) began with the development of oceanic basin. The rifting process is believed to be associated with the formation of the Columbia supercontinent, which happened from 2.5 Ga to 1.8 Ga and was coeval with the onset of Aravalli orogeny's rifting basin.[8] The opening of another sedimentary basin during the Delhi orogeny (~-1,100 Ma) coincided with the time where the supercontinent Columbia broke up, and the cessation of basin development followed by a compressional phase was concurrent with the assembly of Rodinia.[8][16] The deposition of the upper Vindhyan Supergroup may also denote the final episode of Rodinia formation.[8] Several geochemical analyses show that detrital zircon samples obtained from the Marwar basin are highly linked to the breakup phase of Rodinia and the assembly phase of Gondwana.[8]

Map gallery

Reconstruction of Columbia supercontinent

Reconstruction of Columbia supercontinent Reconstruction of Rodinia supercontinent

Reconstruction of Rodinia supercontinent Godwana supercontinent

Godwana supercontinent

See also

References

- Mishra, D.C.; Kumar, M. Ravi. Proterozoic orogenic belts and rifting of Indian cratons: Geophysical constraints. Geoscience Frontiers. 2013 March. 5: 25–41.

- Mckenzie, N. Ryan; Hughes, Nigel C.; Myrow, Paul M.; Banerjee, Dhiraj M.; Deb, Mihir; Planavsky, Noah J. New age constraints for the Proterozoic Aravalli–Delhi successions of India and their implications. Precambrian Research. 2013 November. 238: 120–128.

- Verma, P.K.; Greiling, R.O.. Tectonic evolution of the Aravalli Orogen (NW India): an inverted Proterozoic rift basin?. Geol Rundsch. 1995 August. 84: 683–696.

- Kaur, Parampreet; Zeh, Armin; Chaudhri, Naveen; Gerdes, Axel; Okrusch, Martin. Archaean to Paleoproterozoic crustal evolution of the Aravalli mountain range, NW India, and its hinterland: The U-Pb and Hf isotope record of detrital zircon. Precambrian Research. 2011 March. 187: 155–164.

- Lente, B. Van; Ashwal, L.D.; Pandit, M.K.; Bowring, S.A.; Torsvik, T.H.. Neoproterozoic hydrothermally altered basaltic rocks from Rajasthan, northwest India: Implications for late Precambrian tectonic evolution of the Aravalli Craton. Precambrian Research. 2009 January; 170: 202–222.

- Rao, V. Vijaya; Prasad, B. Rajendra; Reddy, P.R.; Tewari, H.C.. Evolution of Proterozoic Aravalli Delhi Fold Belt in the northwestern Indian Shield from seismic studies. Tectonophysics. 2000 June. 327 (1–2): 109–130.

- Sinha-Roy, S.; Malhotra, G.; Guha, D.B.. A transect across Rajasthan Precambrian terrain in relation to geology, tectonics and crustal evolution of south-central Rajasthan. In: Sinha-Roy, S., Gupta, K.R. (Eds.), Continental Crust of NW and Central India. Geological Society, India. 1995. 31: 63–89.

- Meert, Joseph G.; Pandit, Manoj K.. The Archean and Proterozoic history of Peninsular India: tectonic framework or Precambiran edimentary basins in India. In: Mazumder, R. & Eriksson, P. G. (eds), Precambrian Basins of India: Stratigraphic and Tectonic Context. Geological Society, London. 2015 March. 43: 29–54

- Roy, A.B., Jakhar, S.R., 2002. Geology of Rajasthan (Northwest India). Precambrian to Recent. Scientific Publishers (India), Jodhpur, 421 pp.

- Gupta, S.N.; Arora, Y.K.; Mathur, R.K.; Iqbaluddin, Prasad B.; Sahai, T.N.; Sharma, S.B.. The Precambrian geology of the Aravalli region, southern Rajasthan and northeastern Gujarat. Geological Survey India. 1997. 123: 262.

- Choudhary AK, Gopalan K, Sastry CA (1984) Present status of the geochronology of the Precambrian rocks of Rajasthan. Tectonophysics 105: 131–140.

- Naqvi SM, Divakar Rao V, Hari Narain (1974) The protoconti- nental growth of the Indian Shield and the antiquity of its rift valleys. Precambrian. Res 1: 345–398.

- Condie, K.C.; Beyer, E.; Belousova, E.; Griffin, W.L.; O’Reilly, S.Y.. U–Pb isotopic ages and Hf isotopic composition of single zircons: the search for juvenile Precambrian continental crust. Precambrian Research. 2005. 139: 42–100.

- Mathur, RK; Prasad, B; Sharma, BS; Iqbaluddin. Synsedimentational shoreline volcanism in Aravalli of Rajasthan. Geological Survey India News. 1978.

- Deb, M., Talwar, A.K., Tewari, A., Banerjee, A.K., 1995. Bimodal volcanism in South Delhi fold belt: a suite of differentiated felsic lava at Jharivav, north Gujarat. In: Sinha-Roy, S., Gupta, K.R. (Eds.), Continental Crust of NW and Central India. Geol. Soc. India, Memoir 31, pp. 259–278.

- Turner, Candler C.; Meert, Joseph G.; Pandit, Manoj K.; Kamenov, George D.. A detrital zircon U-PB and HF isotopic transect across the Son Valley sector of the Vindhyan Basin India: Implications for basin evolution and paleogeography. Gondawa Research. 2013 June. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2013.07.009

- Azmi, R.J.; Joshi, D.; Tewari, B.N.. 2008. A synoptic view on the current discordant geo- and biochronological ages of the Vindhyan Supergroup, central India. Journal of Himalayan Geology. 29: 177–191.