Tasman Bridge disaster

The Tasman Bridge disaster occurred on the evening of 5 January 1975, in Hobart, the capital city of Australia's island state of Tasmania, when a bulk ore carrier travelling up the Derwent River collided with several pylons of the Tasman Bridge, causing a large section of the bridge deck to collapse onto the ship and into the river below. Twelve people were killed, including seven crew on board the ship, and the five occupants of four cars which fell 45 m (150 feet) after driving off the bridge. Hobart was cut-off from its eastern suburbs, and the loss of the road connection had a major social impact. The ship’s master was officially penalised for inattention and failure to handle his vessel in a seamanlike manner.

_(16200189861).jpg) Tasman Bridge from east following collision, 1975 | |

| Locale | |

|---|---|

| Hobart, Tasmania, Australia | |

| Collapse | |

| Hit by Lake Illawarra | 5 January 1975 |

| Crosses | |

| Derwent River, Hobart | |

Collision and collapse

The collision occurred at 9:27 p.m. (Australian Eastern Summer Time UTC+11) on Sunday 5 January 1975. The bulk carrier Lake Illawarra, carrying 10,000 tonnes of zinc ore concentrate, was heading up the Derwent River to offload its cargo to the Electrolytic Zinc Company at Risdon, upstream from Hobart and about 3 km from the bridge. The 1,025 m long main viaduct of the bridge was composed of a central main navigation span, two flanking secondary navigation spans, and 19 approach spans. The ship was off course as it neared the bridge, partly due to the strong tidal current but also because of inattention by the ship's master, Captain Boleslaw Pelc.[1] Initially approaching the bridge at eight knots, Pelc slowed the ship to a 'safe' speed. Although the Lake Illawarra was capable of passing through the bridge's central navigation span, the captain attempted to pass through one of the eastern spans.

Despite several changes of course, the ship proved unmanageable due to its insufficient speed relative to the current. In desperation the captain ordered 'full speed astern', at which point all control was lost. The vessel drifted towards the bridge midway between the central navigation span and the eastern shore, crashing into the pile capping of piers 18 and 19, bringing three unsupported spans and a 127 m section of roadway crashing into the river and onto the vessel's deck. The ship listed to starboard and sank within minutes in 35 m of water a short distance to the south. Seven crew members on the Lake Illawarra were trapped and drowned. The subsequent marine court of inquiry found that the captain had not handled the ship in a proper and seamanlike manner, and his certificate was suspended for six months.[2]

As the collision occurred on a Sunday evening, there was relatively little traffic on the bridge. While no cars were travelling between the 18th and 19th pylons when that section collapsed, four cars drove over the gap, killing five occupants. Two drivers managed to stop their vehicles at the edge, but not before their front wheels had dropped over the lip of the bridge deck. One of these cars contained Frank and Sylvia Manley.

Sylvia Manley: "As we approached, it was a foggy night ... there was no lights on the bridge at the time. We just thought there was an accident. We slowed down to about 40 km/h and I'm peering out the window, desperately looking to see the car ... what was happening on the bridge. We couldn't see anything but we kept on travelling. The next thing, I said to Frank, "The bridge is gone!" And he just applied the brakes and we just sat there swinging.[3] As we sat there, we couldn't see anything in the water. All we could see was a big whirlpool of water and apparently the boat was sinking. So with that, we undid the car door and I hopped out."[4]

Frank Manley: "[Sylvia] said "The white line, the white line's gone. Stop!" I just hit the brakes and I said "I can't, I can't, I can't stop." And next thing we just hung off the gap...when I swung the door open, I could see, more or less, see the water...and I just swung meself towards the back of the car and grabbed the headrest like that to pull myself around.[4] There's a big automatic transmission pan underneath [the car] – that's what it balanced on."[3]

The other car contained Murray Ling, his wife Helen and two of their children. They were driving over the bridge in the east-bound lanes when the span lights went out."I knew something bad must have happened so I slowed down". Ling then noticed several cars ahead of him seemingly disappear as they drove straight over the edge and slammed his foot on the brakes. He stopped the car inches from the drop. A following car, caught unaware by the unexpected stop, drove into the rear of Ling's car, pushing its front wheels over the breach. He, too, eased himself and his young family out of the car, then stood there horrified as two other cars ignored his attempts to wave them down, raced past, one of which actually swerved around to avoid him, and hurtled over the edge into the river. A loaded bus full of people swerved and skidded slamming into the side railings after being waved down by Ling.[5]

Emergency response

Private citizens living nearby were on the scene early, even before the ship had sunk. Three of these were Jack Read in his H28 yacht Mermerus, David Read in a small launch, and Jerry Chamberlain, who had their boats moored in Montagu Bay close by. These and others, and many shore-based residents, were responsible for saving many of the crewmen from the Lake Illawarra. Those in small craft acted alone in very difficult circumstances with falling cement, live wires, and water from a broken pipe above, until the water police arrived on the scene. A large number of other organisations were involved in the emergency response, including police, ambulance service, fire brigade, Royal Hobart Hospital, Civil Defence, the Hobart Tug Company, Marine Board of Hobart, Public Works Department, Transport Commission, HydroElectric Commission, Hobart Regional Water Board, the Australian Army and the Royal Australian Navy. At 2:30 am, a 14-man Navy Clearance Diving Team flew to Hobart to assist Water Police in the recovery of the vehicles which had driven off the bridge. Two vehicles were identified on 7 January; one was salvaged that day and the second three days later. Another vehicle was found buried under rubble on 8 January.

A comprehensive survey of the wreck of the Lake Illawarra was completed by 13 January. The divers operated in hazardous conditions, with little visibility and strong river currents, contending with bridge debris such as shattered concrete, reinforced steel rods, railings, pipes, lights, wire and power cables. Strong winds on the third day brought down debris from the bridge above, including power cables, endangering the divers working below.[6]

A total of 12 people died in the disaster: seven crew of the MV Lake Illawarra and five motorists.

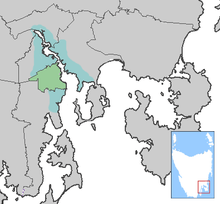

A divided city

Facilities

The collapse of Tasman Bridge isolated two sides of the city which had heavily relied upon it for most daily activities.[7] 30% of Hobart's residents lived on the eastern shore and were effectively isolated. The day after the incident, as 30,000 residents set out for work, they found that the former three-minute commute over the bridge had turned into a 90-minute trip.[8] Within an hour of the incident, the Sullivans Cove Ferry Company started services across the river, and continued its services throughout the night.

Three private ferries and a government vessel were in place the next day. People on the eastern shore quickly became isolated, as most schools, hospitals, businesses and government offices were located on the western shore. Prior to the disaster, many services on the eastern shore were severely lacking.[9] Access to medical services in particular posed problems for residents in the east, as services consisted only of local clinics. Hobart's hospitals—the Royal Hobart Hospital and the Calvary Hospital—were located on the western shore. What was previously a short drive across the river became a 50 km (31 mi) trip via the estuary's other bridge in Bridgewater. Most of Hobart's cultural activities, such as theatres, cinemas, the museum and art gallery, restaurants, meeting places, lecture theatres and the botanical gardens, were located on the western shore.[10]

Social effects

The disaster caused a variety of social and psychological difficulties. Although comparatively minor in loss of life and damage, it presented a problem beyond the capacity of the community to resolve.[8] The disaster had unique characteristics and occurred at a time when the effects of disasters on communities were not well understood. "Opportunities for the community to be involved in the response to the disaster and the physical restoration of infrastructure were minimal because of the nature of the event. It is likely that this lack of community involvement contributed to the enduring nature of the effects of the disaster on a number of individuals."[10]

A study of police data found that in the six months after the disaster, crime rose 41% on the eastern shore, while the rate on the city's western side fell. Car theft rose almost 50% in the isolated community, and neighborhood quarrels and complaints rose 300%.[8] Frustration and anger was directed towards the transport services. Visible progress on restoration of the bridge was slow because of the need for extensive underwater surveys of debris and the time required for design of the rebuilding. "The ferry queues did however provide some assistance by providing a forum where people with much in common could vent their frustration."[10] A sociological study described how the physical isolation led to debonding (the setting aside of bonds that constitute the fabric of normal social life). The loss of the Tasman Bridge in Hobart disconnected two parts of the city and had far-reaching effects on the people separated.[11]

The disaster was a major contributor to ferry services being the lifeline for people needing to cross the river for daily work. Bob Clifford was the major operator of ferries at the time, and quickly built more of his small aluminium craft, using his company Sullivans Cove Ferry Company. He later went on to become the major Tasmanian shipbuilder with a firm which continues today, called Incat.

Rebuilding

Repairing the bridge

In March 1975, a Joint Tasman Bridge Restoration Commission was appointed to restore the Tasman Bridge. The Federal Government agreed to fund the project, which began in October that year. The reconstruction included modification of the whole bridge to accommodate an extra traffic lane, allowing for a peak period 'tidal flow' system of three lanes for major flow and two for the minor flow. Approximately one year after the bridge collapse, a temporary two lane Bailey bridge 788 m long, linking the eastern and western shores of the Derwent, was opened.[9]

Specialists in marine engineering undertook an extensive investigation to locate bridge debris. This survey took several months to complete, and parts of the bridge weighing up to 500 tons were accurately located using equipment developed by the University of Tasmania and the Public Works Department. Maunsell and Partners were appointed consultants for the rebuilding project. The firm John Holland was awarded the construction contract.[12] Engineers decided not to replace pier 19 as there was too much debris on the site.[13] The Tasman Bridge was re-opened on 8 October 1977, nearly three years after its collapse.[1] The annual expenditures on the Tasman Bridge reconstruction were $1.7 m in 1974–75; $12.3 m in 1975–76; $13.2 m in 1976–77 and $6.1m in 1977–78.[14]

The engineering design of the Tasman Bridge provided impact absorbing fendering to the pile caps of the main navigation span capable of withstanding a glancing collision by a large ship, but all other piers were unprotected. This disaster shares some common features with the Skyway Bridge collapse in Florida in 1980, and the I-40 bridge disaster in Oklahoma in 2002, both involving collisions with ships. When river traffic "comprises large vessels, even at low speed, the consequences of pier failure can be catastrophic". In the field of structural engineering, the concept of ‘pier-redundant’ bridges refers to a bridge superstructure which does not collapse when a single pier is removed.[15] Two ‘pier-redundant’ bridges have been constructed in Australia – over the Murray River at Berri and at Hindmarsh Island in South Australia. The probability of ship impact is now regularly evaluated by specialist consultants when designing major bridges. One solution is to protect bridge piers through strengthening or the construction of impact-resistant barriers.[16]

The disaster resulted in changes to the regulations pertaining to shipping movements on the Derwent River. In 1987, a system of sensors measuring river currents, tidal height, and wind speed was installed near the bridge to provide data for ship movements in the area.[17] The Marine and Safety (Pilotage and Navigation) Regulations (2007) contains specific provisions dealing with the Bridge, e.g.:

"The master of a vessel approaching the Bridge to navigate it through a span must (a) have the vessel fully under control; and (b) navigate the vessel with all possible care at the minimum speed required to pass safely under the bridge".[18]

Vessels above a certain size are required to be piloted, and vehicle movements on the bridge are temporarily halted when large vessels are to pass underneath the bridge. As an added precaution, it is now mandatory for most large vessels to have a tug in attendance as they transit the bridge in the event that assistance with steerage may be required.

Development on the eastern shore

.jpg)

The disaster stimulated development in Kingborough, a municipality south of Hobart on the western shore, because of the reduced travel times for western shore workers compared to the eastern shore. The eastern shore eventually became a more self-contained community, with a higher level of employment and improved services and amenities, than had been the case prior to the disaster. The previous imbalance between facilities and employment opportunities was redressed as a result of the disaster.[10]

A new bridge crossing the river, the Bowen Bridge, was completed in 1984, a few kilometres north of the Tasman Bridge.

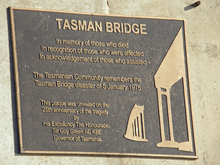

Memorial

A small service, led by members of the Tasmanian Council of Churches, was held on the occasion of the reopening on Saturday 8 October 1977. A large memorial service was eventually held 25 years after the disaster, in January 2000. In his address to the gathering, the Tasmanian Premier Jim Bacon stated that some people were still struggling with the memories of its effects, and he commended the resilience of the community in coping with the disaster. The Governor at the time, Sir Guy Green, described the pain and loss of loved ones and the social and economic disruption. He paid tribute to the efforts of emergency services personnel in responding to the disaster. He said that the "eastern shore had emerged more self-sufficient in the wake of the tragedy" and that "Tasmanians were now stronger, more self-reliant and mature".[10] A plaque commemorating the tragedy was affixed to the main bridge support on the eastern shoreline.

References

- "The Tasman Bridge Collapse". Emergency Management Australia. Archived from the original on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- "Tasmanian Shipwrecks". Oceans Enterprises. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

- "The Monaro Man". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. March 2002. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

- "Tasman Bridge". Australia Network. 15 January 2007. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

- http://messui.the-chronicles.org/incident/1975_hobart.pdf

- "Australian Maritime Issues 2005" (PDF). Royal Australian Navy. 13 April 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2008. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- Lee, T (1981). Adjustment in the Urban System: The Tasman Bridge Collapse and Its Effects Upon Metropolitan Hobart. Pergamon.

- "The Bridge of Sighs". Time Magazine. 16 August 1976. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- "Tasmanian Year Book 2000". Australian Bureau of Statistics. December 2006. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- "Tasman Bridge Disaster: 25th Anniversary Memorial Service" (PDF). Emergency Management Australia. 13 March 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- Gordon, R. "The Social Dimension of Disaster Recovery" (PDF). Recovery. Emergency Management Australia. p. 111. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- "Tasman Bridge Statistics". Government of Tasmania. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- "Tasman Bridge Disaster". Government of Tasmania. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- "Australian Road Financing Statistics 1970–1980" (PDF). Bureau of Transport Economics. 9 March 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2008. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- "Safety First for Bridge Design" (PDF). AustRoads, republished by Cambridge University Dept of Engineering. 3 May 2004. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- "Collapse resistance and robustness of bridges" (PDF). International Association for Bridge Maintenance Safety and Management. 1 April 2008. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- Holbrook, Martin (1999). "Real Time System to Aid Vessel Manoeuvering in the Derwent River". Coasts & Ports 1999: Challenges and Directions for the New Century; Proceedings of the 14Th Australasian Coastal and Ocean Engineering Conference and the 7Th Australasian Port and Harbour Conference. Engineers Australia: 279. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "Marine and Safety (Pilotage and Navigation) Regulations". Government of Tasmania. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

Further reading

- Lewis, T. By Derwent Divided: the story of Lake Illawarra, the Tasman Bridge and the 1975 disaster. Darwin: Tall Stories, 1999. ISBN 0-9577351-1-1

- Ludeke, M. Ten events shaping Tasmania's history. Hobart, Tas. : Ludeke, 2006 ISBN 0-9579284-2-4

- Johnson, S. "Over the Edge!" Reader's Digest, Nov. 1977.