Tagma (biology)

In biology, a tagma (Greek: τάγμα, plural tagmata – τάγματα) is a specialized grouping of multiple segments or metameres into a coherently functional morphological unit. Familiar examples are the head, the thorax, and the abdomen of insects.[1] The segments within a tagma may be either fused (such as in the head of an insect) or so jointed as to be independently moveable (such as in the abdomen of most insects).

Usually the term is taken to refer to tagmata in the morphology of members of the phylum Arthropoda, but it applies equally validly in other phyla, such as the Chordata.

In a given taxon the names assigned to particular tagmata are in some sense informal and arbitrary; for example, not all the tagmata of species within a given subphylum of the Arthropoda are homologous to those of species in other subphyla; for one thing they do not all comprise corresponding somites, and for another, not all the tagmata have closely analogous functions or anatomy. In some cases this has led to earlier names for tagmata being more or less successfully superseded. For example, the one-time terms "cephalothorax" and "abdomen" of the Araneae, though not yet strictly regarded as invalid, are giving way to prosoma and opisthosoma. The latter two terms carry less of a suggestion of homology with the significantly different tagmata of insects.

Tagmosis

The development of distinct tagmata is believed to be a feature of the evolution of segmented animals, especially arthropods. In the ancestral arthropod, the body was made up of repeated segments, each with similar internal organs and appendages. One evolutionary trend is the grouping together of some segments into larger units, the tagmata. The evolutionary process of grouping is called tagmosis (or tagmatization).[2]

The first and simplest stage was a division into two tagmata: an anterior "head" (cephalon) and a posterior "trunk". The head contained the brain and carried sensory and feeding appendages. The trunk bore the appendages responsible for locomotion and respiration (gills in aquatic species). In almost all modern arthropods, the trunk is further divided into a "thorax" and an "abdomen", with the thorax bearing the main locomotory appendages. In some groups, such as arachnids, the cephalon (head) and thorax are hardly distinct externally and form a single tagma, the "cephalothorax" or "prosoma". Mites appear to have a single tagma with no obvious external signs of either segments or separate tagmata.[2]

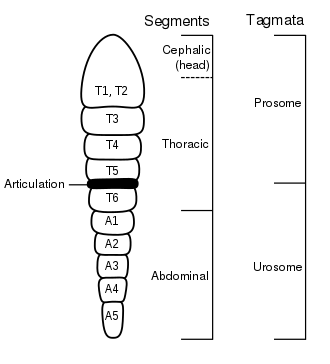

Tagmosis proceeded differently in different groups of arthropods, so that the tagmata are not derived from corresponding (homologous) segments, even though the same names may be used for the tagmata.[3] Copepods (a kind of crustacean) provide an example. The basic copepod body consists of a head, a thorax with six segments, ancestrally each with a swimming leg, and an abdomen with five appendageless segments. Except in parasitic species, the body is divided functionally into two tagmata, that may be called a "prosome" and a "urosome", with an articulation between them allowing the body to flex. Different groups of copepods have the articulation at different places. In the Calanoida, the articulation is between the thoracic and abdominal segments, so that the boundary between the prosome and urosome corresponds to the boundary between thoracic and abdominal segments. However, in the Harpacticoida, the articulation is between the fifth and sixth thoracic segments, so that the sixth thoracic segment is in the urosome (see the diagram).[4]

Tagmosis is an extreme form of heteronomy, mediated by Hox genes and the other developmental genes they influence.[5]

Terminology

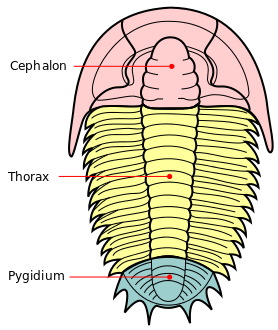

The tagmata of a trilobite: cephalon, thorax and pygidium

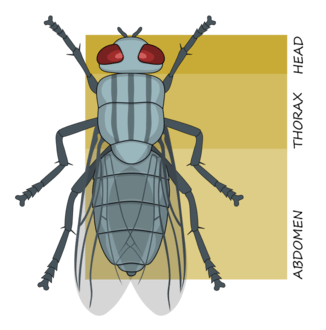

The tagmata of a trilobite: cephalon, thorax and pygidium Tagmata of an insect: head (cephalon), thorax and abdomen

Tagmata of an insect: head (cephalon), thorax and abdomen- Tagmata and major appendages of a spider: cephalothorax or prosoma and abdomen or opisthosoma

The number of tagma and their names vary among taxa. For example, the extinct trilobites had three tagmata: the cephalon (meaning head), the thorax (literally meaning chest, but in this application referring to the mid-portion of the body), and the pygidium (meaning rump). The Hexapoda, including insects, also have three tagmata, usually termed the head, thorax, and abdomen.

The bodies of many arachnids, such as spiders, have two tagmata, as do the bodies of some crustaceans: in both groups the anterior tagma may be called the cephalothorax (meaning head plus chest) or the prosoma or prosome (meaning "fore-part of body"). The posterior tagma may be called the abdomen. In those arachnids that have two tagmata, the abdomen is also called the opisthosoma. In crustaceans, the posterior tagma is also called the pleon or the urosome (meaning the tail part); alternatively, "pleon" may refer only to the abdominal segments incorporated into the posterior tagma, the thoracic segments in this tagma being called the "pereon".[6]

References

- D. R. Khanna (2004). Biology of Arthropoda. Discovery Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-7141-897-8.

- Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 518–520.

- Ruppert, Fox & Barnes 2004, p. 518.

- Barnes et al. (2001), p. 198.

- Alessandro Minelli (2003). "Body Regions: Their Boundaries and Complexity". The development of animal form: ontogeny, morphology, and evolution. Cambridge University Press. pp. 79–105. ISBN 978-0-521-80851-4.

- Barnes et al. (2001), p. 191.

Bibliography

- Barnes, R.S.K.; Calow, P.; Olive, P.J.W.; Golding, D.W. & Spicer, J.I. (2001). The Invertebrates: a Synthesis (3rd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-632-04761-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ruppert, E.E.; Fox, R.S. & Barnes, R.D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)