Rigvedic rivers

Rivers, such as the Sapta Sindhavah ("seven rivers" Sanskrit: सप्तसिन्धवः)[1] play a prominent part in the hymns of the Rig Veda, and consequently in early Hindu religion. Vedic texts have a wide geographical horizon, speaking of oceans, rivers, mountains and deserts. “Eight summits of the Earth, three shore or desert regions, seven rivers.” (asthau vyakhyat kakubhah prthivyam tri dhanva yojana sapta sindhun RV.I.35.8).

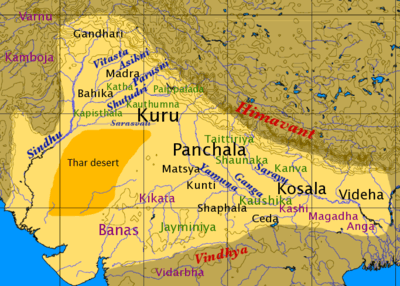

The Vedic land is a land of the seven rivers flowing into the ocean. It encompasses the regions from Gandhara to Kurukshetra.

Mythology

A recurring theme in the Yajurveda is that of Indra slaying Vritra (literally "the obstacle"), liberating the rivers; in a variant of the myth, Indra smashes the Vala cave, releasing the cows that were within. Though the two myths are separate,[2] rivers and cows are often poetically correlated in the Rigveda, for example in 3.33, a notable hymn describes the crossing of two swollen rivers by the chariots and wagons of the Bharata tribe:

Seven Rivers

The Seven Rivers are a group of seven chief rivers of uncertain or fluctuating identification (the number seven is of greater importance than the exact members of the group)- compare the Saptarishi of the Avesta (and also the later seven seas and the seven climes) . The Avesta's hapta həndu are preemptively equated with the Vedic Sapta Sindhavaḥ or vis-a-vis: in Vendidad 1.18 these are described to be the fifteenth of the sixteen lands created by Mazda.[4] Note: The term Sapta Sindhava, commonly used in Hindi and other Indian languages, is the nominative plural in Sanskrit (dropping the final visarga in conformity with the convention when expressing Sanskrit words in modern languages). Sapta Sindhu, often seen in English, is in the singular, and is therefore ungrammatical.

Identity of the Seven Rivers

It is not entirely clear how the Seven Rivers were intended to be enumerated. They are often located in northern India / eastern Pakistan. If the Sarasvati and the five major rivers of India are included (Shutudri/Sutlej, Parushni/Ravi, Ashikni/Chenab, Vitasta/Jhelum, Vipasha/Beas, the latter all tributaries of Sindhu/Indus), one river is missing, probably the Kubha. Other possibilities include the Arjikiya or Sushoma; compare also the list of ten rivers, both east and west of the Indus, in the Nadistuti sukta, RV 10.75. In 6.61.10, Sarasvati is called "she with seven sisters" (saptasvasā) indicating a group of eight rivers, the number seven being more important than the individual members (see also saptarshi, hapta karšuuar /haft keshvar in Avestan), so that the list of the Sapta Sindhava may not have been fixed or immutable. In RV 10.64.8 and RV 10.75.1, three groups of seven rivers are referred to (tríḥ saptá sasrâ nadíyaḥ "thrice seven wandering rivers"), as well as 99 rivers. The Sapta-Sindhava region was bounded by Saraswati in the east, by the Sindhu in the west and the five in between were Satudru, Vipasa, Asikni, Parusni and Vitasta.

Not all researchers agree with this interpretation. According to other interpretation, "Sapta Sindhu" is only a small subset of the Rig Vedic terrain and its disproportionate importance derives from it being the original homeland of the victorious Bharata Trutsu tribe.

Geography of the Rigveda

Identification of Rigvedic rivers is the single most important way of establishing the geography of the early Vedic civilization. Rivers with certain identifications stretch from eastern Afghanistan to the western Gangetic plain, clustering in the undivided Punjab (the region's name means "five rivers").

A number of names can be shown to have been re-applied to other rivers as the center of Vedic culture moved eastward from the central Vedic heartland in undivided Punjab. It is possible to establish a clear picture for the latest phase of the Rigveda, thanks to the Nadistuti sukta (10.75), which contains a geographically ordered list of rivers. The most prominent river of the Rigveda is the 4925 kilometers (3061 miles) long Sarasvati, next to the 3249 kilometers (2019 miles) long Indus. The Rig Veda mentions Saraswati river as between Yamuna to the East and river Sutlej to the west. The Mahabharata clearly talks about this massive Sarasvati drying up. The mighty and perennial Sarasvati flowed from the Himalayan Glaciers to the Rann of Kutch where it emptied into the Arabian sea. Dwaraka of Lord Krishna was part of this civilization.[5] 2704 kilometers (1690 miles) long Ganges River was also flowing at that time into the Bay of Bengal. Saraswati started drying up in 4000 BC due to tectonic plate shifts which blocked the glacier source and changed the course of the Yamuna & Sutlej Rivers. This made River Saraswati dependant on rains, not glacial ice. Gradually the whole river was buried under the Thar desert sand dunes, leaving only disconnected pools and lakes here and there. The Yamuna river soon started pouring into The Ganges River instead of Saraswati and The Sutlej River started pouring into The Indus River.[6] When the Saraswati river started drying up, the whole civilization may have migrated to fertile lands – some to Ganges, some to south west of India from Goa to Kerala.

List

In the geographical organization of the following list, it has to be kept in mind that some names appearing both in early and in late hymns may have been re-applied to new rivers during the composition of the Rigveda.

Northwestern Rivers (western tributaries of the Indus):

- Trstama

- Susartu

- Anitabha (listed once, in 5.53.9, with the Afghan rivers Rasa (Avestan Rangha/Raŋhā), Kubha, Krumu, Sarayu (Avest. Harōiiu)

- Rasa (on the upper Indus) (often a mythical river, Avestan Rangha, Scythian Rha)

- Svetya (Gilgit)[7]

- Kubha (Kabul), Greek Kophēn

- Krumu (Kurrum)

- Mehatnu (along with the Gomati and Krumu)

- Srivastu/Suvastu (Swat) in RV 8.19.37)

- Gauri (Panjkora)

- Kusava (Kunar)

The Indus and its minor eastern tributaries:

Central Rivers (rivers of the Punjab):

East-central Rivers (rivers of Haryana):

- Sarasvati (References to the Sarasvati river in the Rigveda are identified with the present-day Ghaggar River, although originally it might have been the name of the Arghandab and Helmand rivers, as a possible locus of early Rigvedic references.)[8]

- Drsadvati, Apaya (RV 3.23.4, Mahabharata Apaga.)

Eastern Rivers:

- Asmanvati (Assan)

- Yamuna

- Ganga

- Sarayu in Uttar Pradesh

- Gomati or Adi Ganga in Uttar Pradesh (Gomti)

- Gandaki

- Silamavati

- Urnavati

- Yavyavati (Zhob river)

See also

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Rigvedic rivers |

- Ap (water)

- Aryan migration

- Nadistuti sukta

- Old European hydronymy

- Out of India theory

- Rigvedic deities

- River goddess

- Samudra

- Zhetysu - 7 rivers of Central Asia

References

- e.g. RV 2.12; RV 4.28; RV 8.24

- H.-P. Schmidt, Brhaspathi and Indra, Wiesbaden 1968

- "Rig Veda: Rig-Veda, Book 3: HYMN XXXIII. Indra". www.sacred-texts.com.

- Gnoli 1989 pp.44–46

- Prasad, R. U. S. (25 May 2017). River and Goddess Worship in India: Changing Perceptions and Manifestations of Sarasvati. Routledge. ISBN 9781351806541.

- "Microsoft Word - Jan10E.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- S., Prasad, R. U. (2017). River and goddess worship in India : changing perceptions and manifestations of Sarasvati. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 9781351806558. OCLC 988293338.

- Kochhar, Rajesh (1999), "On the identity and chronology of the Ṛgvedic river Sarasvatī", in Roger Blench; Matthew Spriggs (eds.), Archaeology and Language III; Artefacts, languages and texts, Routledge, p. 262, ISBN 0-415-10054-2

Further reading

- Bryant, Edwin (2001), The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-513777-9

- B. B. Lal (2005). The Homeland of the Aryans. Evidence of Rigvedic Flora and Fauna and Archaeology. Aryan Books. ISBN 8173052832.

- Braj Basi Lal (2015). The Rigvedic People - 'Invaders'?/'Immigrants'? or Indigenous?. Aryan Books International. ISBN 978-81-7305-535-5.

- Braj Basi Lal (2002). The Sarasvatī flows on: the continuity of Indian culture. Aryan Books International. ISBN 978-81-7305-202-6.

- Chakrabarti, D. K., & Saini, S. (2009). The problem of the Sarasvati River and notes on the archaeological geography of Haryana and Indian Panjab. New Delhi: Aryan Books International.

- Danino, Michel (2010), The Lost River - On the trail of the Sarasvati, Penguin Books India

- Eck, Diana L. (2012), India: A Sacred Geography, Clarkson Potter/Ten Speed/Harmony, ISBN 978-0-385-53191-7

- Gherardo Gnoli, De Zoroastre à Mani. Quatre leçons au Collège de France (Travaux de l’Institut d’Études Iraniennes de l’Université de la Sorbonne Nouvelle 11), Paris (1985)

- Gupta, S.P. (ed.). 1995. The lost Saraswati and the Indus Civilization. Kusumanjali Prakashan, Jodhpur.

- K. D. Sethna The Problem of Aryan Origins, 1980, 1992; ISBN 81-85179-67-0

- S.C. Sharma. 1974. The description of the rivers in the Rig Veda. The Geographical Observer, 10: 79-85.

- Shrikant G. Talageri, The Rigveda, a historical analysis, Aditya Prakashan, New Delhi (chapter 4)

- Michael Witzel, Tracing the Vedic dialects in Dialectes dans les litteratures Indo-Aryennes ed. Caillat, Paris, 1989, 97–265.