Sundevall's roundleaf bat

Sundevall's roundleaf bat (Hipposideros caffer), also called Sundevall's leaf-nosed bat,[2] is a species of bat in the family Hipposideridae.

| Sundevall's roundleaf bat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Hipposideridae |

| Genus: | Hipposideros |

| Species: | H. caffer |

| Binomial name | |

| Hipposideros caffer (Sundevall, 1846) | |

| |

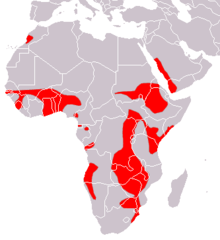

| Sundevall's roundleaf bat range | |

These bats are very similar in appearance to the closely related Noack's roundleaf bat, and the two have in the past been considered to be the same species. Although more recent research suggests that they are distinct, taken together, they possibly represent a species group containing a number of cryptic species or subspecies that have yet to be distinguished.[2][3]

Description

Sundevall's roundleaf bat is a medium-sized bat, with a head-body length of 8 to 9 cm (3.1 to 3.5 in), and a wingspan of 20 to 29 cm (7.9 to 11.4 in). Adults have a body weight of 8 to 10 g (0.28 to 0.35 oz). They have long fur, which may be either grey or a bright golden-orange in colour, and brown wings. The fur is generally paler on the underside of the body.[4]

The bats have large, rounded, ears with a well-developed antitragus, and a horseshoe-shaped nose-leaf, with a distinctive small projection on either side. There is also an additional serrated ridge of skin behind the main nose-leaf. Both females and males have an extra pair of teats in the pubic region. Although these are vestigial in the males, they can be as long as 4 cm (1.6 in) in some females (almost half the body length), yet are never functional. These false teats may be only present to allow the young something to hold on to while clinging to their mothers.[4]

Distribution and habitat

Sundevall's roundleaf bat is a relatively common species, and is found in almost every African country south of the Sahara, as well as in Morocco, Yemen, and parts of Saudi Arabia. Four subspecies are currently recognised, although the precise geographic range of each is not yet clear:[2]

- H. c. angolensis

- H. c. caffer

- H. c. nanus

- H. c. tephrus

The bat is most commonly found in savannah habitats, and avoids the dense rainforests of central Africa. It is, however, very wide-ranging, and has also been reported in Acacia shrubland, bushveld, and in coastal and mopane forests.[1][5]

Behaviour

Sundevall's roundleaf bat feeds primarily on moths, which may form up to 92% of its diet. They are apparently selective in their choice of moths, and have been observed to avoid certain species of arctiid moths that advertise their unpleasant taste by emitting ultrasonic clicks.[6] They have also been found to eat small amounts of beetles, flies, and other insects. Known predators on this species include bat hawks.

The bats are relatively slow-flying, but highly manoeuvrable in the air, even being able to hover in place for brief periods. They mostly catch moths or other prey in midair, but are able to snatch fluttering insects on the ground, using their echolocation calls to distinguish the rapid movement of insect wings from other nearby clutter. The calls consist of a constant frequency component lasting about 6 ms, followed by a short frequency-modulated downward sweep. The frequency of the calls varies with geographic locality, but is typically about 140 kHz.[7]

During the day, Sundevall's roundleaf bats roost in caves, tree hollows, or manmade structures such as mines or attics. Some cave roosts may host exceptionally large colonies, with as many as 500,000 individuals having been reported from one cave in Gabon.[1] The colonies seem to have a "harem" structure, with dominant males monopolising access to a number of females.[5] Although they do not truly hibernate, they do sometimes enter torpor during cold weather.[4]

Reproduction

Breeding occurs during the winter in populations in the northern and southern parts of the range. In equatorial regions, although only a single breeding season occurs each year for any given population, this may be aligned with either the Northern or Southern Hemisphere winter, so some populations geographically close to one another may, nonetheless, be reproductively isolated. Gestation lasts about three to four months, but in some populations, delayed implantation of the embryo causes birth of the young until five to seven months after mating.[4]

The female gives birth to a single young, which is initially blind and partially hairless. Although the pups develop deciduous teeth while still in the womb, these have already disappeared by the time they are born.[4] They begin to fly at about one month of age,[8] and are fully weaned at about three months, when they are close to the adult size. They reach sexual maturity at one or two years of age.[4]

References

- Richards, L.R.; Cooper-Bohannon, R.; Kock, D.; Amr, Z.S.S.; Mickleburgh, S.; Hutson, A.M.; Bergmans, W.; Aulagnier, S. (2020). "Hipposideros caffer". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T80459007A22094271. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T80459007A22094271.en. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- Simmons, Nancy B. (2005). "Hipposideros caffer". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Vallo, P., A. Guillén-Servent, P. Benda, D. Pires and P. Koubek (2008). "Variation of mitochondrial DNA in the Hipposideros caffer complex (Chiroptera: Hipposideridae) and its taxonomic implications." Acta Chiropterologica 10(2): 193-206.

- Wright, G.S. (2009). "Hipposideros caffer (Chiroptera: Hipposideridae)". Mammalian Species. 845: 1–9. doi:10.1644/845.1.

- Bell, G.P. (1987). "Evidence of a harem social system in Hipposideros caffer (Chiroptera: Hipposideridae) in Zimbabwe". Journal of Tropical Ecology. 3 (1): 87–90. doi:10.1017/S0266467400001139.

- Dunning, D.C. & Krüger, M. (1996). "Predation upon moths by free-foraging Hipposideros caffer". Journal of Mammalogy. 77 (3): 708–715. doi:10.2307/1382675. JSTOR 1382675.

- Fenton, M.B. (1986). "Hipposideros caffer (Chiroptera: Hipposideridae) in Zimbabwe: morphology and echolocation calls". Journal of Zoology. 210 (3): 347–353. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1986.tb03638.x.

- Menzies, J.I. (1973). "A study of leaf-nosed bats (Hipposideros caffer and Rhinolophus landeri) in a cave in northern Nigeria". Journal of Mammalogy. 54 (4): 930–945. doi:10.2307/1379087. JSTOR 1379087.