Orange leaf-nosed bat

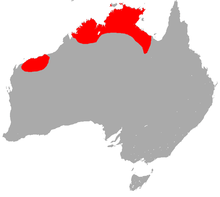

The orange leaf-nosed bat (Rhinonicteris aurantia) is a bat in the family Hipposideridae.[3] It is the only living species in the genus Rhinonicteris[3] which is endemic to Australia, occurring in the far north and north-west of the continent. They roost in caves, eat moths, and are sensitive to human intrusion.

| Orange leaf-nosed bat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Rhinonycteridae |

| Genus: | Rhinonicteris |

| Species: | R. aurantia |

| Binomial name | |

| Rhinonicteris aurantia (Gray, 1845)[2] | |

| |

| Orange leaf-nosed bat range | |

Description

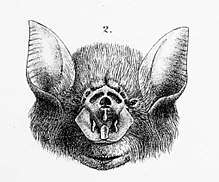

A small bat weighing 7–11 grams that resides in large colonies of subterranean environs, usually caves and abandoned mines. The colour of the fur is variable between individuals, brownish, a reddish orange shade, lemon-yellow or white.[4][5] The forearm measurement range from 42–46.[4] A complex structure—a characteristic of some bats referred to as 'nose-leaf'—is broad and flattened at the base, with a central gap, similar to a horseshoe-shape of related species. The top of the leaf-shaped structure is scalloped, and the nasal pits deeply recessed, an opening behind this structure leads from an enlarged secretory gland.[4] The noseleaf does not have by any forwardly projecting parts at the deep cleft of the lower section.[5] The ears, which are smaller than similar species, are sharply pointed at the top.[4]

The measurements for the head and body combined are 43 to 53 millimetres.[5]

Taxonomy

Rhinonicteris aurantia is a species of bat, currently allied to the family Hipposideridae that groups some 'leaf-nosed bats'. The first description was published by John Edward Gray in 1845, placing the species in genus Rhinolophus.[2][6] The syntype for the species in located at the British Museum of Natural History, the note stating it was collected at Port Essington "near the hospital".[6] Gould elucidates the type's collection as an animal shot from the air by Dr. Sibbald of the Royal Navy.[7] [6]

A western form is distinguished from the northern population, superficially similar yet genetically distinct, this remote group in is identified separately for its conservation status assessment as the Pilbara form and may be a separate taxon.[4][5]

The genus name published as Rhinonycteris Gray, J.E. 1866 has been regarded as a later correction by Gray, but this has also been determined to be an unjustified emendation.[8][6] The specific epithet has also taken the spelling "aurantius", likewise considered incorrect in this generic combination.[7][3] Common names include the orange leaf-nosed bat, and the golden or orange horseshoe bat.[6]

Distribution

The range of Rhinonicteris aurantia is across the north of the continent—the Top End and Kakadu—which encompasses the northernmost part of the Northern Territory, and extends into of Western Australia and north-west Queensland. A geographically separate population is found in the Pilbara region of the north-west.[4] The westernmost point of the distribution range is around Derby, Western Australia and extends from here to the east at Lawn Hill, Queensland.[5]

One site noted for its large colony, numbering in the thousands, is located at Tolmer Falls in the Lichfield National Park. A preference is also given to larger sites amongst the Kimberley limestone caves, where the largest colonies of the species occur. At Tunnel Creek the bat is found co-habiting and hunting with several other bat species.[4]

The habit of flying close to the ground sees the species collected by the grille of road trains, frequently transporting them en route from Katherine to the north of the state.[4]

Ecology

As with many bats in arid regions, they are insectivores.[4] R. aurantia is found in large caves cohabiting with others bat species. These include the yellow-lipped Vespadelus douglasorum, northern bentwing Miniopterus orianae, the western cave bat and ghost bat Macroderma gigas.[4] The preferred cave environ is warm and humid, other opportunities for roosting sites include tree hollows. The colony may number in the thousands, but the individuals also cluster in groups of twenty and over.[9]

The diet of insects includes various beetles, weevils, bugs, wasps and ants, but the common prey is moths. They venture out several times during their night-time hunting activities.[9]

A new species of parasite, Opthalmodex australiensis,[10] was found on a specimen of the bat, this minute organism seems to occur in the eye as a low grade infestation and subsist on epithelial tissue.[11] Another organism, Chiroptella geikiensis, a species of the chigger family Trombiculidae was discovered on specimens of this bat.[12][13]

The colony may desert a site if intruded upon by visitors, the species is noted as even more susceptible to human activities near their roosts than other bats. Direct threats include destruction of habitat by mining, clearing for agriculture and pastoralism that results in the loss of food resources.[9]

A species describing fossil material found at the Riversleigh site in Northern Queensland, Brachipposideros nooraleebus, closely resemble this species.[14] The only described species of the genus is based on Miocene fossils also found at Riversleigh.[15]

The conservation status of the species is least concern.[1] The population identified as the Pilbara form is vulnerable to extinction.[5]

References

- Armstrong, K.; Burbidge, A.A. & Woinarski, J. (2017). "Rhinonicteris aurantia.". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T7923A22118433. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T19589A21998626.en.{{cite iucn}}: error: |doi= / |page= mismatch (help)

- Gray, J.E. 1845. Description of some new Australian animals. Appendix. pp. 405-411 in Eyre, E.J. (ed.). Journals of Expeditions of Discovery into Central Australia and Overland from Adelaide to King George's Sound in the Years 1840-1; sent by the colonists of South Australia, with the sanction and support of the Government: including an account of the manners and customs of the Aborigines and the state of their relations with Europeans. London : T. & W. Boone Vol. 1. [405].

- Simmons, N.B. (2005). "Order Chiroptera". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Richards, G.C.; Hall, L.S.; Parish, S. (photography) (2012). A natural history of Australian bats : working the night shift. CSIRO Pub. pp. 12, 16, 17, 18, 42, 48, 157. ISBN 9780643103740.

- Menkhorst, P.W.; Knight, F. (2011). A field guide to the mammals of Australia (3rd ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press. p. 146. ISBN 9780195573954.

- "Species Rhinonicteris aurantia (J.E. Gray, 1845)". Australian Faunal Directory. Australian Government. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- Gould, John (1863). The mammals of Australia. 3. Printed by Taylor and Francis, pub. by the author. pp. pl.35 et seq.

- Gray, John Edward (1866). "A revision of the genera of Rhinolophidae, or horseshoe bats". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 1866: 81–83. ISSN 0370-2774.

- "Orange Leaf-nosed Bat, Scientific name: Rhinonicteris aurantius". The Australian Museum. 2018-10-12. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- "Ophthalmodex australiensis". Atlas of Living Australia. Australian Government. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- Woeltjes, A. G. W.; Lukoschus, F. S. (1981). "Parasites of Western Australia XIV Two new species of Ophthalmodex Lukoschus and Nutting (Acarina: Prostigmata: Demodicidae) from the eyes of bats". Records of the Western Australian Museum. 9 (3): 307–313. ISSN 0312-3162.

- Lee Goff, M. (1979). "Species of chigger (Acari Trombiculidae) from the orange horseshoe bat Rhinonicteris aurantius". Records of the Western Australian Museum. 8 (1): 93–96. ISSN 0312-3162.

- Halliday, R. B. (1998). Mites of Australia: A Checklist and Bibliography. Csiro Publishing. p. 2093. ISBN 9780643105898.

- Hand, Suzanne J. (1993). "First skull of a species of Hipposideros (Brachipposideros) (Microchiroptera: Hipposideridae). from Australian Miocene sediments". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 33: 179–192. ISSN 0079-8835.

- Foley, Nicole M.; Thong, Vu Dinh; Soisook, Pipat; Goodman, Steven M.; Armstrong, Kyle N.; Jacobs, David S.; Puechmaille, Sébastien J.; Teeling, Emma C. (February 2015). "How and Why Overcome the Impediments to Resolution: Lessons from rhinolophid and hipposiderid Bats". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 32 (2): 313–333. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu329. PMC 4769323. PMID 25433366.