Suakin

Suakin or Sawakin (Arabic: سواكن Sawákin) is a port city in northeastern Sudan, on the west coast of the Red Sea, it was formerly the region's chief port, but is now secondary to Port Sudan, about 50 kilometres (30 mi) north.

Suakin سواكن | |

|---|---|

Suakin, El-Geyf mosque | |

Suakin Location in Sudan | |

| Coordinates: 19°06′N 37°20′E | |

| Country | |

| District | Port Sudan |

| Population (2009 (est.)) | |

| • Total | 43,337 |

| Designations | |

|---|---|

| Official name | Suakin-Gulf of Agig |

| Designated | 2 February 2009 |

| Reference no. | 1860[1] |

Suakin used to be considered the height of medieval luxury on the Red Sea, but the old city built of coral is now in ruins. In 1983 it had a population of 18,030 and the 2009 estimate is 43,337.[2] Ferries run daily from Suakin to Jeddah in Saudi Arabia.

Etymology

Sawakin (سواكن) is Arabic, meaning "dwellers" or "stillnesses."

The Beja name for Suakin was U Suk, possibly from the Arabic word suq, meaning market. In Beja, the locative case for this is isukib, whence Suakin might have derived.[3] The spelling on Admiralty charts in the late 19th century was "Sauakin" but in the popular press "Suakim" was predominant.[4]

History

Ancient

Suakin was likely Ptolemy's Port of Good Hope, Limen Evangelis, which is similarly described as lying on a circular island at the end of a long inlet.[3] Under the Ptolemies and Romans, though, the Red Sea's major port was Berenice to the north. The growth of the Muslim caliphate then shifted trade first to the Hijaz and then the Persian Gulf.

Medieval

The collapse of the Abbasids and growth of Fatimid Egypt changed this and Al-Qusayr and Aydhab became important emporia, trading with India and ferrying African pilgrims to Mecca. Suakin was first mentioned by name in the 10th century by al-Hamdani, who says it was already an ancient town. At that time, Suakin was a small Beja settlement, but it began to expand after the abandonment of the port of Badi to its south. The Crusades and Mongol invasions drove more trade into the region: there are a number of references to Venetian merchants residing at Suakin and Massawa as early as the 14th century.

One of Suakin's rulers, Ala al-Din al-Asba'ani, angered the Mamluk sultan Baybars by seizing the goods of merchants who died at sea nearby. In 1264, the governor of Qus and his general Ikhmin Ala al-Din attacked with the support of Aydhab. Al-Asba'ani was forced to flee the city. The continuing enmity between the two towns is testified to by reports that after the destruction of Aydhab by Sultan Barsbay in 1426, the refugees who fled to Suakin instead of Dongola were all slaughtered.[5]

The Beja were originally Christian. Despite the town's formal submission to the Mamluks in 1317, O. G. S. Crawford believed that the city remained a center of Christianity into the 13th century. Muslim immigrants such as the Banu Kanz gradually transformed this: ibn Battuta records that in 1332 there was a Muslim "sultan" of Suakin, al-Sharif Zaid ibn-Abi Numayy ibn-'Ajlan, who was the son of a Meccan sharif. Following the region's inheritance laws, he had inherited the local leadership from his Bejan maternal uncles.[5]

In the fifteenth century, Suakin was briefly part of the Adal Sultanate.[6][7]

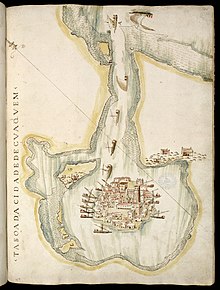

Portuguese

Suakin Island in Sudan was for the Mamluks from Egypt and Syria a very important port, in the west coast of the Red Sea. Nevertheless from the 15th century on the Portuguese with their superior naval power, gained dominance in the region, attacking and making alliances with Muslim reigns of Africa and Middle east, [8]leading to the capture of Suakin in 1513 by the Portuguese [9]. The Ottoman Empire, to avoid more attacks from the Portuguese in Egypt [10], made an effort to establish control of the Red Sea by conttroling the port during the reign of Sultan Selim I.

Ottoman

In 1517, the Ottoman sultan Selim I added the port to the territory of the Ottoman Empire, and after a brief occupation by the Funj, it was thereafter the residence of the pasha of the Ottoman province of Habesh. The Ottomans restored the two main mosques - Shafii and Hanafi, strengthened the walls of the fort and built new roads and buildings.[11][12][13] As the Portuguese explorers discovered and perfected the sea route around Africa and the Ottomans were unable to stop this trade, the local merchants began to abandon the town.

Some trade was kept up with the Sultanate of Sennar, but by the 18th and 19th centuries, the Swiss traveler Johann Ludwig Burckhardt found two-thirds of the homes in ruin.[3] The Khedive Isma'il received Suakin from the Ottomans in 1865 and attempted to revitalize it: Egypt built new houses, mills, mosques, hospitals, even a church for immigrant Copts.

British and colonial rule

The British Army was involved at Suakin in 1883–1885 and Lord Kitchener was there in this period leading the Egyptian Army contingent. Suakin was his headquarters and his force survived a lengthy siege there.

The Australian colonial forces of Victoria offered their torpedo boat HMVS Childers, and gunboats HMVS Victoria and HMVS Albert, which arrived in Suakin on 19 March 1884 on their delivery voyage from Britain, only to be released as fighting had moved inland. They departed on 23 March, arriving in Melbourne on 25 June 1884. An essentially civilian military force of 770 men from New South Wales, including some of the Naval Brigade, arrived in Suakin in March 1885 and served until mid-May.[14]

After the Mahdi's defeat, the British preferred to develop the new Port Sudan rather than engage in the extensive rebuilding and expansion that would be necessary to make Suakin comparable. By 1922, the last of the British had left.[3]

Buildings of Suakin

A detailed description of the buildings of Suakin, including measured plans and detailed sketches, can be found in The Coral Buildings of Suakin: Islamic Architecture, Planning, Design and Domestic Arrangements in a Red Sea Port by Jeanne-Pierre Greenlaw, Kegan Paul International, 1995, ISBN 0-7103-0489-7.

Climate

Suakin has a very hot desert climate (Köppen BWh) with brutally hot and humid, though dry, summers and very warm winters. Rainfall is minimal except in November, when easterly winds can give occasional downpours: in November 1965 as much as 445 millimetres (17.5 in) fell, but in the whole year from July 1981 to June 1982 no more than 3 millimetres (0.1 in) was recorded.[18]

| Climate data for Suakin (Sawakin) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 26 (79) |

26 (79) |

27 (81) |

30 (86) |

33 (91) |

38 (100) |

42 (108) |

41 (106) |

37 (99) |

33 (91) |

30 (86) |

27 (81) |

32 (90) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 19 (66) |

19 (66) |

20 (68) |

21 (70) |

24 (75) |

25 (77) |

28 (82) |

29 (84) |

26 (79) |

25 (77) |

23 (73) |

21 (70) |

23 (73) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 8 (0.3) |

2 (0.1) |

1 (0.0) |

1 (0.0) |

1 (0.0) |

0 (0) |

8 (0.3) |

6 (0.2) |

0 (0) |

16 (0.6) |

54 (2.1) |

28 (1.1) |

125 (4.7) |

| Source: Weatherbase[19] | |||||||||||||

References

- "Suakin-Gulf of Agig". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "World Gazeteer". Archived from the original on 19 September 2012.

- Berg, Robert: Suakin: Time and Tide Archived 2010-01-13 at the Wayback Machine. Saudi Aramco World.

- "Facts about Suakim". The South Australian Advertiser (Adelaide, SA : 1858 - 1889). Adelaide, SA: National Library of Australia. 23 April 1885. p. 6. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- Dahl, Gudrun & al: "Precolonial Beja: A Periphery at the Crossroads." Nordic Journal of African Studies 15(4): 473–498 (2006).

- Owens, Travis. BELEAGUERED MUSLIM FORTRESSES AND ETHIOPIAN IMPERIAL EXPANSION FROM THE 13TH TO THE 16TH CENTURY (PDF). NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL. p. 23.

- Pouwels, Randall. The History of Islam in Africa. Ohio University Press. p. 229.

- Feio, Gonçalo. "O ensino e a aprendizagem militares em Portugal e no Império, de D. João III a D. Sebastião: a arte portuguesa da guerra" (PDF).

- Couto, Diogo. "Da Asia De Diogo De Couto: Dos Feitos, Que Os Portuguezes Fizeram ..., Parte 7".

- Campos, Nuno. [O ensino e a aprendizagem militares em Portugal e no Império, de D. João III a D. Sebastião: a arte portuguesa da guerra. "A Casa de Atouguia, os Últimos Avis e o Império. Dinâmicas entrecruzadas na carreira de D. Luís de Ataíde (1516-1581)"] Check

|url=value (help). - Why is Sudan's Suakin island important for Turkey?

- Turks return to Suakin Island after two centuries

- Turkey renovating historic Ottoman-era sites on Suakin island in Sudan

- Before the Anzac Dawn: A military history of Australia before 1915 Chapter 5: "Australian naval defence", Edited: Craig Stockings, John Connor (2013), accessed 23 June 2016

- "Suakin: 'Forgotten' Sudanese island becomes focus for Red Sea rivalries". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- Lin, Christina. "Neo-Ottoman Turkey's 'String of Pearls'". Asia Times. Archived from the original on October 22, 2019.

The same year, Turkey signed trade and investment deals with Sudan, including to lease Suakin Island for 99 years as a possible military base. The island is located in the Red Sea close to Saudi Arabia and was once a key naval base of the Ottoman Empire.

- "Turkey to Restore Sudanese Red Sea Port and Build Naval Dock". Voice of America. 24 December 2017.

- Monthly rainfall for Suakin

- "Weatherbase: Historical Weather for Sawakin, Sudan". Weatherbase. 2011. Retrieved on November 24, 2011.

External links

- Comparative Vocabularies of the Languages Spoken at Suakin: Arabic, Hadendoa, Beni-Amer

- Pictures of Suakin on Atlas Obscura

- Suakin: Time and Tide — on Saudi Aramco World

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Suakin. |