Su Hui (poet)

Su Hui (simplified Chinese: 苏蕙; traditional Chinese: 蘇蕙; pinyin: Sū Huì, Fourth Century CE) was a Chinese poet of the Middle Sixteen Kingdoms period (304 to 439) during the Six Dynasties period. Her courtesy name is Ruolan (traditional Chinese: 若蘭; simplified Chinese: 若兰; pinyin: Ruòlán). Su is famous for her extremely complex "palindrome" (huiwen 回文) poem, apparently having innovated this genre, as well as producing the most complex example to date.[1]

Biography

The Jin Dynasty (265–420) had briefly unified the Chinese empire, in 280, but from 291 to 306 a multi-sided civil war known as the War of the Eight Princes raged through northern China, devastating that part of the country. For the first thirteen years this was an all-out struggle for power among princes and dukes. Then in 304 CE the leader of the formerly independent ethnic nation of the Northern Xiongnu declared independence, under its newly declared Grand Chanyu, Liu Yuan (later Prince Han Zhao). Various other non-Han Chinese groups became involved, in what is known as the Wu Hu uprising. By 317 the last Jin prince left standing, now as emperor, ruled an empire reduced to its former southern area, and the former northern part of the Jin empire had been subdivided into a number of independent states. In 351, the state of Former Qin was founded, and by 376 it had succeeded in unifying northern China. Su Hui was a poet of the kingdom of Former Qin (351-394). She was from a literate family, in what is now Fufeng County, in Shaanxi Province. She was the third daughter of Su Daozhi. Su Hui married at sixteen (fifteen, by Western reckoning), and went to live with her husband, Dou Tao, to what is now Qinzhou District, Tianshui, Prefecture, in Gansu Province, where he was the governor.

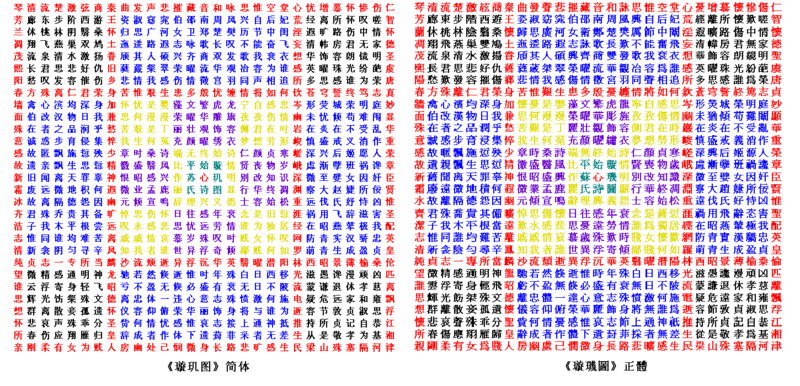

Palindrome Poem: Xuanji Tu

Su Hui was known for an important and unusual poem. This was described in contemporary sources as shuttle-woven on brocade, meant to be read in a circle, and consisting of 112 or else 840 characters. By the Tang period, the following story about the poem was current:[2]

- Dou Tao of Qinzhou was exiled to the desert, away from his wife Lady Su. Upon departure from Su, Dou swore that he would not marry another person. However, as soon as he arrived in the desert region, he married someone. Lady Su composed a circular poem, wove it into a piece of brocade, and sent it to him.[3]

Another source, naming the poem as Xuanji Tu (Picture of the Turning Sphere), claims that it was a palindromic poem comprehensible only to Dou (which would explain why none of the Tang sources reprinted it), and that when he read it, he left his desert wife and returned to Su Hui.[4]

The text of the poem was circulated continuously in medieval China and was never lost, but during the Song Dynasty it became scarce. The 112 character version was included in early sources. The earliest excerpts of the 840 character version date from a 10th-century text by Li Fang. Several 13th century copies were attributed to famous women of the Song Dynasty, but falsely so.[5] In the Ming Dynasty the poem became quite popular and scholars discovered 7,940 ways to read it. It was also mentioned in the story Flowers in the Mirror. The poem is in the form of a twenty-nine by twenty-nine character grid, and can be read forward or backwards, horizontally, vertically, or diagonally, as well as within its color-coded grids.[6]

During the Qing Dynasty the character 心 (heart) was added to the center of the poem, so that it now has 841 characters.

Other poems

Other poems attributed to Su Hui are extant, but seem to date from the Ming Period.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Su Hui. |

- Classical Chinese poetry

- Classical Chinese poetry genres

- Six dynasties poetry

Notes

- Hinton, 105

- Wang, 51

- Wang, 51

- Wang, 52

- Wang, 80-81

- Hinton, 108

References

- Hinton, David (2008). Classical Chinese Poetry: An Anthology. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-10536-7 / ISBN 978-0-374-10536-5.

- Wang, Eugene. "Patterns Above and Within: Picture of the Turning Sphere and Medieval Chinese Astral Imagination." In Wilt Idema, ed., Book by Numbers, 49-89. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2007.

Interwiki links

- Chinese Wikipedia article on Su Hui (In Chinese)

- Chinese Wikipedia article on Su Hui's poem (In Chinese) With color text and image versions of her Xuanji Tu.