Josip Juraj Strossmayer

Josip Juraj Strossmayer (Croatian pronunciation: [jǒsip jûraj ʃtrǒsmajer]; German: Joseph Georg Strossmayer;[1] 4 February 1815 – 8 April 1905) was a Croatian politician, Roman Catholic bishop, and benefactor.[2]

His Excellency Josip Juraj Strossmayer | |

|---|---|

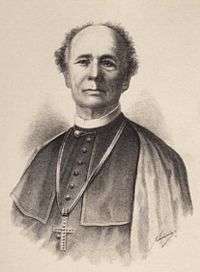

Josip Juraj Strossmayer by Josip Franjo Mücke | |

| Born | 4 February 1815 |

| Died | 8 April 1905 (aged 90) |

| Resting place | Đakovo Cathedral, Đakovo, Croatia 45°18′27.9″N 18°24′39″E |

| Other names | Joseph Georg Strossmayer |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna |

| Occupation | Bishop, politician, professor |

| Years active | 1838–1905 |

| Known for | Founder of Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts |

| Political party | People's Party (until 1880) Independent People's Party (1880–1905) |

| Movement | Illyrian Movement |

| Signature | |

Early life and rise as a cleric

.jpg)

Strossmayer was born in Osijek to a Croatian family. His great-grandfather was an ethnic German immigrant from Styria who had married a Croatian woman. He finished a gymnasium in Osijek, graduated theology at the Catholic seminary in Đakovo, and earned a PhD in philosophy at a high seminary in Budapest, at the age of 20.[2]

In 1838 he worked as a vicar in Petrovaradin, before moving to Vienna in 1840 to the Augustineum and the University of Vienna, where he received another doctorate in philosophy and Canon law in 1842. In 1847 he was made the Habsburg palace chaplain (a position he would hold until 1859), and named one of the rectors of the Augustineum.[2]

On 18 November 1849 he was made the bishop of Bosnia and Syrmia with seat in Đakovo. The proclamation was made by emperor Franz Joseph and at the proposal of Croatian ban Josip Jelačić. Pope Pius IX confirmed the imperial decree on 20 May 1850. He was made a bishop on 8 September 1850, and officially instated in Đakovo on 29 September the same year. Upon installment as bishop, he declared his motto to be Everything for the faith and the homeland. Strossmayer inherited a wealthy diocese: it had 70,000 acres (280 km²) of mixed forests, pastures, arable land and vineyards, with developed cattle and horse breeding facilities, and it generated a yearly income of 150,000 to 300,000 forints.

Croatian politics

In 1860 he became the leader of the People's Party and remained at its head until 1873. He had previously befriended Ján Kollár in Pest and worked with Czech politicians František Palacký and František Rieger on their common ideals of cultural and political association of the Slavic peoples. He strove to obtain more rights for the Slavs within the Monarchy. He advocated federalization, merging of the kingdoms of Dalmatia and Croatia, as well as the introduction of Croatian language into public administration and schools.

In 1861, Strossmayer made an influential speech in front of the Croatian Parliament regarding the relations of Croatia and Hungary, where he stated federalization as a goal, and advocated the merging of Međimurje and Rijeka with Croatia. In 1866, the Parliament elected him the president of the Croatian regnikolar deputation (regnikolarna, that which represents the people of the kingdom), a committee that was to negotiate terms of statehood with Hungary, but which failed to successfully make a deal. Instead, the Croatian-Hungarian Settlement of 1868 was passed which was less favorably inclined towards the Croatian cause — and which Strossmayer protested with respect to decreased autonomy in the areas of budget and finances.

In 1872 the Parliament formed another regnikolar deputation for the revision of the Settlement, and Strossmayer was its member, but they again failed in their task. This made Strossmayer retire from active political life and from the leadership of the People's Party. He later sided with the Independent People's Party which was in the opposition and which protested the rule of ban Khuen Hedervary (1883–1903), and insisted on the merger of all Croatian lands under the Kingdom of Hungary. In 1888 he retired from public politics after the Emperor had rebuked him for favoring the Russians and opposing the Hungarians.

Cultural policy

Strossmayer was instrumental in the founding of the Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts in 1866, as well as the re-establishment of the University of Zagreb in 1874.[3][4] He initiated the building of the Academy Palace (completed in 1880) and set up The Strossmayer Gallery of Old Masters (1884) in Zagreb.[5]

Strossmayer aided the creation of the printing house in Cetinje, helped found the Matica slovenska and actively supported Matica srpska, the national culture societies of the Slovenes and the Serbs, respectively. In 1861 he had the book Bulgarian Folk Songs by the Miladinov Brothers from Macedonia printed in Zagreb. He also had several Glagolitic missals printed in the spirit of restoring the Slavonic liturgy that connected the two Christian religions of the South Slavs, and revering the work of saints Cyril and Methodius.

Catholic diplomacy

Strossmayer supported the union of all south Slavic peoples, and promoted religious unification through the use of the Slavonic rite both in the Catholic and Orthodox Churches. He served as the papal nuncio for Serbia and visited that country seven times between 1852 and 1886, and he also helped establish the concordat between the Holy See and the state of Montenegro in 1866.

In 1869 and 1870 he attended the First Vatican Council in Rome. He made his mark as one of the vocal opponents of the unlimited power of the Pope as well as the doctrine of papal infallibility. He made a speech, completely in Latin, in which he defended protestantism, and which "called forth a storm of indignation from the majority, which finally forced the speaker to leave the tribune."[6][2] Another speech is a forgery which is falsely attributed to him;[2] in this forged speech it is written against the dogma of Papal infallibility: "Ah ! if He who reigns above wishes to punish us, making His hand fall heavy on us, as He did on Pharaoh, He has no need to permit Garibaldi's soldiers to drive us away from the eternal city. He has only to let them make Pius IX. a god, as we have made a goddess of the blessed Virgin."[7][8] He later yielded on the issue of infallibility,[2] and he also headed the Slavic deputations to Rome in 1881 and 1888 which succeeded in convincing Pope Leo XIII to allow the south Slavs of Croatia and Dalmatia to retain Slavonic in the Roman Rite liturgy as well as in the Byzantine Rite.

Personal life

Since the early days of his episcopate, he was a close friend of Franjo Rački, the most renowned Croatian historian of his time. When the Academy was founded in 1867, Strossmayer was named chief sponsor, and Rački its President. In 1894, when Rački died, Strossmayer wrote: I lost my dearest friend... I lost a part of myself... the good half of everything I have created was his thought, his credit and his glory. Their friendship was well documented in a series of four books containing their letters, compiled by historian Ferdo Šišić.[9]

Josip Juraj Strossmayer died in Đakovo at the age of 90.

Legacy

Strossmayer continuously used the money obtained from his diocese to fund the building of schools, galleries and churches, notably the ornamental Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul in Đakovo whose building he oversaw between 1866 and 1882,[2] and which he dedicated to the glory of God, unity of the churches, concord and love of his people. The cathedral of Đakovo was the most grandiose object built by Strossmayer during his 55 years as a bishop: he also opened the printing house in Đakovo, the boys' seminary in Osijek, supported the main theological seminary and the arrival of nuns in Đakovo to help the female youth and caritative efforts, established new parishes throughout the diocese, organized missions for the laity, and finally wrote hundreds if not thousands of pastoral letters sent to the diocese as well as to other parts of Croatia, and elsewhere.

Strossmayer is credited with monetary and organizational support for a wide variety of public works in Croatia: schools, gymnasiums, public libraries, helping the poor in remote areas, even building roads, and donating building material for St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican.

The university of the city of Osijek is named after him, and a large statue of Strossmayer is located in the park that the Academy building overlooks. The city of Đakovo built him a memorial museum in 1991. One of the main streets in Sarajevo carries his name. A monument in the Sofia district of Ilinden commemorates Strossmayer's contribution to Bulgarian culture. Also, an important square in Prague is named after him.

Bishop Nikolaj Velimirović dedicated a booklet entitled Religion and Nationality in Serbia to Strossmayer: “to the memory of the great Croatian patriot Bishop Strossmayer on the centenary of his birth (1815–1915)".[10]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Josip Juraj Strossmayer. |

- Arthur J. May, The Hapsburg Monarchy, 1867–1914 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1968), 73. Contemporaries spelled the name "Straussmeyer".

- Klemens Löffler (1912). "Catholic Encyclopedia: Joseph Georg Strossmayer". The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 14. Robert Appleton Company, New York. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- "History of the University of Zagreb". University of Zagreb. 2005. Retrieved 2010-09-30.

Bishop Josip Juraj Strossmayer in 1861 proposed to the Croatian Parliament that a legal basis be established for the founding of the University of Zagreb. During his visit to Zagreb in 1869 the Emperor Franz Joseph signed the Decree on the Establishment of the University of Zagreb.

- Josip Juraj Strossmayer (1861-04-29). "Akademija znanosti - put prema narodnom obrazovanju". Speech in the Croatian Parliament (in Croatian). Wikisource. Retrieved 2010-09-30.

- "Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts - The Founding of the Academy". Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts. 2007. Archived from the original on 2010-06-06. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- Joseph Kirch (1912). "Catholic Encyclopedia: Vatican Council". The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 15. Robert Appleton Company, New York. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- Bishop Strossmayer's Speech in the Vatican Council of 1870. Loizeaux brothers. p. 23.

- ""The Sensational speech of Bishop Joseph Georg Strossmayer in the Vatican Council I (1870 AD)"?". www.bible.ca. Retrieved 2020-07-10.

- Polić, Maja (2011). "Nekadašnja Rijeka i Riječani, s osvrtom na korespondenciju Rački – Strossmayer". Problemi sjevernog Jadrana (in Croatian) (11): 39–71. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- Markovich, Slobodan G. (2017). "Activities of Father Nikolai Velimirovich in Great Britain during the Great War". Balcanica. 48: 152.

Further reading

- Jelčić, Dubravko (2005). "Ljetopis Josipa Jurja Strossmayera" (PDF). Izabrani književni i politički spisi I. Stoljeća hrvatske književnosti (in Croatian). Zagreb: Matica hrvatska. pp. 53–55. ISBN 953-150-285-4. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Bishop Strossmayer's Speech in the Vatican Council of 1870". Plymouth Brethren Archive. Retrieved 2020-06-29.