Stromeferry

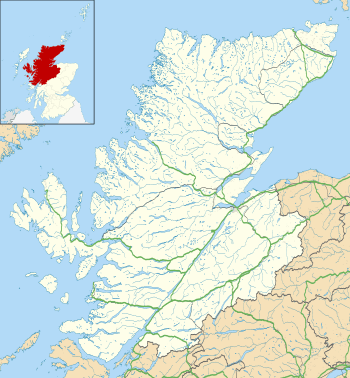

Stromeferry (Scottish Gaelic: Port an t-Sròim) is a village, located on the south shore of the west coast sea loch, Loch Carron, in western Ross-shire, Scottish Highlands and is in the Scottish council area of Highland. Its name reflects its former role as the location of one of the many coastal ferry services which existed prior to the expansion of the road network in the 20th century.

Stromeferry

| |

|---|---|

Stromeferry Location within the Highland council area | |

| OS grid reference | NG864347 |

| Council area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | STROME FERRY |

| Postcode district | IV53 |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

It is served by Stromeferry railway station and is close to the A890 road. Stromeferry is on the southern bank of Loch Carron; Strome Castle is opposite on the northern bank.

.jpg)

The village is referred to in Iain Banks's novel Complicity, where the narrator describes the road sign marking the village, which states "Strome Ferry (No ferry)".

Some local shinty players once competed as "Stromeferry (No Ferry) United".[1]

The village has been subject of various development proposals focussing on the derelict hotel. In November 2007, W.A. Fairhurst & Partners, on behalf of the Helmsley Group, secured an outline planning consent for reinstating the hotel and building a number of new homes.

The Ferry

Stromeferry lies next to the narrowest part of Loch Carron and for many years, there was a ferry service here to North Strome. This provided a link with the first road built in 1809 along the north side of the loch.[2] Completion of the Stromeferry bypass (A890) along the south-eastern shore of the loch made the ferry service redundant and it ceased operating in 1970. At that time, there were two vessels providing the service. The larger of the two, Pride of Strome, measuring 16m long x 5m wide, was built in 1962 by Forbes of Sandhaven.[3] The smaller, Strome Castle, measuring 9m long x 3m wide, was built in 1958 by Nobles of Fraserburgh.[4] Both boats now lie wrecked on the shore of Loch Carron between North Strome and Lochcarron.

A temporary ferry service operated during October 2008 as loose rocks made local roads unsafe and alternative access was required during repair works.[5]

In January 2012, Highland Council chartered two vessels to provide a temporary ferry service after a series of rockfalls closed the A890 road.[6] The 61-seater cruise boat Sula Mhor operating from nearby Plockton carried school pupils and other foot passengers from the Lochcarron and Applecross areas to Plockton High School. The six-vehicle turntable vessel MV Glenachulish that normally operates the summer-only Glenelg-Kylerhea ferry service was pressed into service between the old ferry slipways at Stromeferry and North Strome. The 10-minute traverse of Loch Carron avoids a 140-mile (230 km) road detour via Inverness.[7]

Railway

Stromeferry was the original terminus of the Dingwall and Skye Railway opened in 1870 . Trains connected with steamer services from the pier to the islands of Skye, Lewis and mainland villages. The village expanded rapidly including the construction of a hotel serving rail and ferry passengers.[8] Following the extension to railway line to Kyle of Lochalsh which was completed in 1897 and provided a much shorter sea crossing to the islands, Stromeferry declined in importance.

Stromeferry Riot

Observance of the Sabbath was strong in the Highlands in the 19th century and the railway company's running of trains on Sundays caused considerable controversy among the local population. On 3 June 1883, Stromeferry was the scene of a Sabbatarian riot in which over 200 fishermen took possession of the railway terminus to prevent the unloading of fish on a Sunday.[9] Ten men were imprisoned as a result.[10] The involvement of both police and military in breaking the riot was questioned in the House of Commons where it was stated that there was no law preventing Sunday traffic in Scotland.[11]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stromeferry. |

- "Results Archive 2007-2010". Lewis Camanachd. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- "Ferry at Strome Ferry". Am Baile highland history and culture. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Historic Environment Record "Pride of Strome", Stromemore". The Highland Council. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Historic Environment Record Wreck of "Strome Castle" ferry, Strome". The Highland Council. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Strome ferry boat". Am Baile highland history and culture. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Ferries set for introduction at Strome on Monday". Highland Council. Archived from the original on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Public meetings to consult on the reopening of the Stromeferry By-pass". Highland Council. Archived from the original on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- "Strome Hotel, Strome Ferry". Am Baile highland history and culture. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- "Historical perspective for Stromeferry". The Gazetteer for Scotland.

- MacColl, Allan W. (2006). Land, Faith and the Crofting Community:Christianity and Social Community in the Highlands of Scotland, 1843-1893. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-2382-5.

- "Sunday Traffic (Scotland) The Stome Ferry Riots". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 3 August 1883. col. 1482. Retrieved 12 January 2016.