Stroe Leurdeanu

Stroe Leurdeanu, also known as Stroe (sin) Fiera, Stroie Leurdeanu, Stroe Leordeanu, or Stroe Golescu (ca. 1600 – 1678 or 1679), was a Wallachian statesman and political intriguer, son of Logothete Fiera Leudeanu. He began his career with the Wallachian military forces, serving as Spatharios and seeing action in the Polish–Ottoman War of 1633. Related by marriage to the Craiovești dynasty, he emerged as one of the country's most important officials under Prince Matei Basarab: as Vistier, he was in charge of the princely treasury, and also became a regent (or Caimacam) in 1645. Matei also adopted Stroe's son, Istratie Leurdeanu, but in 1651 turned against the family, and found Stroe guilty of embezzlement. He returned to high favor under a new Prince, Constantin Șerban, who made him his Logothete.

| Stroe Leurdeanu | |

|---|---|

Watercolor reproduction of Leurdeanu's votive portrait | |

| Caimacam (Regent of Wallachia) | |

| Reign | August 1645 |

| Predecessor | Matei Basarab |

| Successor | Matei Basarab |

| Reign | 1663, 1664 |

| Predecessor | Grigore I Ghica |

| Successor | Grigore I Ghica |

| Reign | 1672, 1673 |

| Predecessor | Grigore I Ghica |

| Successor | Grigore I Ghica |

| Reign | May 11, 1675 – September 1677 |

| Predecessor | George Ducas |

| Successor | George Ducas |

| Born | ca. 1600 |

| Died | 1678 or 1679 |

| Burial | Sfântul Ioan-Grecesc Church, Bucharest |

| Spouse | 1. Unknown woman 2. Vișa Goleasca 3. Elina of Prooroci (d. 1655) |

| Issue | Istratie Leurdeanu Necula Leurdeanu Nedelco Leurdeanu Costea Leurdeanu Matei Golescu Stroe II Leurdeanu Ghenadie Leurdeanu Axinia Leurdeanca |

| House | Leurdeanu (Golescu) |

| Father | Fiera Leudeanu |

| Mother | Tudora? |

| Religion | Orthodox |

Chased out of the country by the Seimeni rebellion and again during Constantin Șerban's downfall, the Leurdeanus remained at the center of political life into the 1660s. Although he ordered Istratie's execution, Prince Mihnea III used Stroe as his diplomat, causing the latter to be detained as a hostage by the Ottoman Empire. From 1660, he enjoyed the favors of Mihnea's replacement, George Ghica, who kept him as Logothete. Grigore I Ghica appointed Leurdeanu as regent during the Austro–Turkish War. This moment saw the eruption of a conflict between Leurdeanu and the Cantacuzino family. In 1664, he engineered an intrigue which led to the execution of Postelnic Constantin I Cantacuzino.

Sidelined under Radu Leon, Leurdeanu was brought to justice by Antonie Vodă in 1669. Sentenced to death but then pardoned, he was forced to take orders at Snagov Monastery. He escaped and fled abroad, returning to Wallachia as Grigore Ghica retook the throne, and again served as regent during the Polish–Ottoman War of 1672. Befriending Ghica's successor, George Ducas, he was kept by the latter as Logothete, Vornic, and occasional Ispravnic of the throne. He was victorious over the Cantacuzinos in his final years, overseeing the arrest and torture of Constantin II.

Leurdeanu probably died as a monk, at some point before December 1679. He had many sons, but only two are known to have survived him. One was Stroe II, who maintained leading positions at the court of Constantin Brâncoveanu, together with his nephew Radu Golescu. The Leurdeanu line was nevertheless extinguished, and survived into modernity through a collateral branch, the Golescu family.

Biography

Rise

Leurdeanu is seen by various historians as one of the most significant boyars in early modern Romanian history,[1] when Wallachia was an autonomous subject of the Ottoman Empire. He was born ca. 1600 as the son of Wallachia's Great Logothete, Fiera Leudeanu, and as such a relative of Constantin Șerban, who would become Prince of Wallachia in the 1650s.[2] Several sources suggest that Stroe's mother was Tudora, Fiera's second wife and previously the paramour of Prince Michael the Brave; if proven, this would make Stroe a half-brother of Michael's boyaress daughter, Marula Cornățeanca.[3] From his marriages, Fiera also had sons Vintilă, Nedelco and Neagu, none of whom managed to enter titular boyardom; Fiera's daughters include Stanca, who married Balica of Breasta, and an anonymous wife of Vornic Dumitru Dudescu.[4]

Leurdeanu's first assignment appears to have been as Postelnic from June 15, 1625, under Alexandru Coconul; he is next mentioned as Spatharios of the Wallachian military forces on January 8, 1627.[5] His father had his final commission in 1626, dying at some point in 1629.[6] During his subsequent ascent, Stroe was married three times. No surviving document mentions the name of his first wife, though she is known to have given birth to his eldest son, Istratie Leurdeanu.[7] She may also have given birth to two of Stroe's other known sons, Sluger Nedelco and Clucer Costea.[8] Stroe's last two wives are known by name. The first was Vișa Goleasca, related to the Craiovești-Brâncoveanu family—daughter of the Greek Postelnic Fota and niece of Preda Brâncoveanu, she was more distantly related to Matei Basarab, who took the Wallachian throne in 1632.[9] According to family tradition, Vișa had in fact been adopted by her princely relative, meaning that Leurdeanu was symbolically Matei's son-in-law.[10] The third and last of Leurdeanu's wives was another one of Prince Matei's relatives, Elina of Prooroci (died 1655).[11]

An untitled boyar during most of Alexandru IV Iliaș's reign, Stroe returned on April 27, 1629 to serve as Logothete. One record also cites him as Great Stolnic between November 21, 1632 and February 8, 1633, but he continued to be cited as a Logothete after that interval.[12] In October 1633, at the height of a Polish–Ottoman War, he is cited as fighting alongside the Ottoman Army.[13] His tenure as Logothete straddled the rules of Alexandru IV, Leon Tomșa, and Matei Basarab, to October 6, 1635. On December 20, Matei made Leurdeanu a Logothete of the treasury, and later simply a treasurer (Vistier); he held those twin offices to March 2, 1641.[14] Banking on his wife's influence at the court, he obtained the village of Slănicul de Jos in Muscel County, ignoring a rival claim stated by the Vlădescu boyars.[15]

From November 11 to November 23, 1641, Stroe was Wallachia's Great Stolnic, returning as Great Treasurer on December 24, and serving there to February 25, 1651.[16] For most of this interval, he was seconded by his son Istratie.[17] Stroe and Logothete Radu Cocorăscu were fully in charge of Wallachia's government in August 1645, while Prince Matei was în priumblare ("taking leave").[18] During this first portion of his career, Leurdeanu became noted as an art patron and ktitor: by 1646, he had constructed the Orthodox church on his wife's land in Golești; he also refurbished Vieroși Monastery, where before 1647 he had buried a son, Necula (died 1633), and a daughter, Axinia.[19] Vișa was also dead by 1655, when Leurdeanu began litigation against his in-laws over her estate.[20]

First disgrace and return

According to various reports, the childless Prince Matei was grooming Istratie to be his heir on the throne.[21] The Craiovești–Leurdeanu alliance soon gave way to violent rivalry, in circumstances that are not entirely elucidated. According to chronicler Georgius Krauss, jealous boyars suggested to Matei that Istratie was plotting to have him killed.[22] A document dated to 1652 clarifies that Stroe was sacked upon revelations of embezzlement; a 1654 writ left by Constantin Șerban claims that Stroe narrowly escaped decapitation, though he was innocent of the charges.[23] Historian Vasile Novac also notes that the details of the accusation are implausible: Stroe was alleged to have taken 42,500 thaler in one single strike.[24]

According to writer Constantin Gane, the boyars "did not want" Istratie to rule over them, which led them to fabricate charges against him as well.[25] This looming threat caused Istratie to seek protection in territory more directly controlled by the Ottomans. Prince Matei was allegedly "infuriated" by his behavior, persecuting Nedelco and Costea, and confiscating one of the Leurdeanus' village fiefs.[26] However, Krauss also claims that the families eventually reconciled when Matei allowed Istratie to return home. In this account, the Prince ensured that Istratie married well, to Ilinca—daughter of Nicolae Pătrașcu and granddaughter of Michael the Brave.[27] On April 27, 1654, days after Prince Matei's death, Stroe Leurdeanu was made Logothete by Constantin Șerban, who had usurped the throne; the following day, Istratie was reinstated as Postelnic.[28] Stroe's first diplomatic assignment was a mission to the Sublime Porte, obtaining Șerban's recognition by Sultan Mehmed IV.[29]

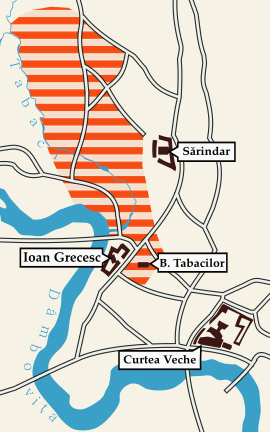

This ascendancy was interrupted by the Seimeni uprising in February 1655. After February 15, he had left Wallachia and taken refuge in the Principality of Transylvania, at Corona (Brașov),[30] being joined there by his wife and children.[31] The rebels ransacked his Bucharest residence, which was located outside Sfântul Ioan-Grecesc Church, in Tabaci mahala.[32] The attack probably involved the mahala's eponymous tanners.[33] Elina's two sisters later testified that the family's wealth was much affected by the uprising, which also destroyed the villages owned by Stroe and took away his "Gypsies" (see Slavery in Romania).[34]

Once Șerban toppled the rebel leader Hrizea of Bogdănei, Leurdeanu could return as Logothete, serving as such from October 13, 1655 to January 30, 1658; during the final year of Șerban's reign, he had again lost his office.[35] His son by Vișa, generally known in sources as Matei Golescu, also climbed through the ranks, serving as Șerban's Spatharios.[36] As Șerban rebelled against the Ottomans in late 1658, Leurdeanu remained by his side. He was attached to Șerban's court as it escaped into Transylvania, but returned by December 9 to be made treasurer by his usurper, Mihnea III.[37] As noted by historian Constantin Rezachevici, Mihnea, in reality a Greek merchant, was entirely without internal support, and asked the Șerbanist boyars to return in order to better secure his throne.[38]

Leurdeanu served as Mihnea's Logothete to August 30, 1659.[39] Again dispatched to Istanbul, he found himself imprisoned as a hostage for two months, as a guarantee that Mihnea would honor his debt to his various Ottoman creditors.[40] At around the same time, Mihnea III accused Istratie Leurdeanu of treason and oversaw his execution.[41] He still nominated Stroe as one of his leading counsels, though, as Rezachevici notes, he could no longer have any guarantee of loyalty from a bereaved father. According to Rezachievici, the surviving Leaurdeanus agreed to an alliance with Mihnea only because of their mutual hatred for an Ottoman protege, Constantin I Cantacuzino, who was emerging as a kingmaker among Wallachia's boyars.[42]

Ghica's protege

Stroe preserved his high office following the appointment of George Ghica as Prince, being confirmed as Logothete on January 21, 1660. He would serve as such to August 28 of the same year, returning as Vornic from January 11, 1661 to December 2, 1665.[43] This tenure also saw him serving two short terms as Wallachian regent, or Caimacam, in 1663 and 1664—alongside Dumitrașcu Cantacuzino; at the time, Ghica was overseeing Wallachian participation in the Austro–Turkish War.[44] From September 1660, Grigore I Ghica's reign sparked a latent civil war between the main branches of the Cantacuzino family and a coalition formed by Greek and Romanian boyars. Though generally known in historiography as the Băleanu party, after Gheorghe Băleanu, the latter camp was in fact organized around Leurdeanu, and, according to Rezachevici, would be more accurately known as the Leurdenists.[45]

According to several Romanian historians, the conflict was unavoidable once Constantin I, at the time a Postelnic, intervened to prevent the sacking of Wallachia by its two Caimacami.[46] Despite being Constantin I's nephew, Dumitrașcu took Stroe's side, and was widely seen as subordinate to his will; their co-conspirators were a Romanian Paharnic Staico Bucșanu, and two prominent Greeks, Balasache Muselim and Nicula Sofialiul.[47] In 1663, Leurdeanu and Dumitrașcu took measures to curb the Postelnic's rise. They reputedly informed Grigore Ghica about the goings-on at the court, alleging in particular that Șerban Cantacuzino intended to take the throne. While Gane believes the accusation was "calumny [and] crazy talk",[48] Rezachevici notes that it was sufficiently plausible.[49] According to the 18th-century chronicler Constantin Căpitanul Filipescu, Ghica had his own suspicions against the Postelnic's sons, as they had rejected his plans for rebelling against the Ottomans with Habsburg support.[50]

Returning to Bucharest with his defeated army, Prince Grigore ordered a confrontation of the boyar witnesses at Craiova, during which Mareș Băjescu took the Postelnic's side and accused the others of perjury.[51] Upon the end of this summary trial in December 1664, Ghica ordered Constantin I's strangling.[52] His killing disgusted the Wallachian public, in particular for its relative secrecy, expediency, and execution method.[53] Șerban Cantacuzino received a less drastic treatment: Ghica ordered his "carving at the nose", which theoretically invalidated him from ever becoming Prince.[54] The clampdown also caused the Postelnic's other heir, Drăghici Cantacuzino, to flee Wallachia; he died at Istanbul in 1667, possibly murdered by Sofialiul.[55]

Ghica himself was deposed by the Porte in December 1664. Trying to gain the upper hand over his rivals, Leurdeanu dispatched to Istanbul a delegation of boyars, who proposed Dumitrașco Buzoianu, a Wallachian squire, as Prince. This "tool in the hand of the Stroe Leurdeanu group" was never considered, and another Greek man, Radu Leon, was sent to rule from Bucharest.[56] Leurdeanu's tenure as Vornic ended on December 2, a date which marked his third refuge into Transylvania.[57] He returned to Wallachia around January 1666, though he no longer held offices at the court under Radu.[58] In 1668, after a period of relative peace, the Cantacuzino party intended to expose Leurdeanu's guilt by suggesting he sign a writ which attested Constantin I's innocence.[59]

The Prince himself acknowledged that Stroe was a murderer, but ignored Cantacuzino pleas to have him tried, and instead allowed the Leurdeanus to increase in size their landed estates. His attempt to appease both sides failed, and his inaction pushed the Cantacuzinos to declare civil war on the Prince in December 1668.[60] According to an apologetic family chronicle, known as Letopisețul Cantacuzinesc, Prince Radu plotted the mass murder of surviving Cantacuzinos, being assisted in this by Leurdeanu and Muselim.[61]

Second disgrace and final return

The arrival on the throne of Antonie Vodă in April 1669 was a major setback in Stroe's political career. While his son Matei was openly persecuted,[62] Leurdeanu was arrested and tried for his participation in Cantacuzino's killing. The Cantacuzinos produced three letters, which reputedly showed Stroe urging Ghica to physically liquidate their patriarch. However, in the anti-Cantacuzino epic known as Cronica Bălenilor, these are described as inauthentic documents.[63] Initially sentenced to death,[64] he was pardoned by the Prince. This was reportedly requested by Constantin I's widow, Elina, who asked that Stroe be instead ordered to spend his remaining years in monastic solitude.[65]

Leurdeanu was stripped of his clothes and made to wear his letters as a necklace, then placed in a wagon which took him from Bucharest to Snagov Monastery.[66] Upon taking orders, he defied his peers by asking to be renamed "Mohamet".[67] Eventually taking the name Silvestru (first recorded in April 1670), he managed a fourth escape into Transylvania in 1671; Prince Antonie sent letters asking that he be apprehended and returned.[68] By then, Leurdeanu's exiled partisans had reached out to the Ottoman overlord, depicting Antonie as an irresponsible ruler.[69] Matei Golescu was still in Wallachia: also in 1670, Antonie heard a complaint from Clucer Tudoran Vlădescu, who wanted to be returned ownership of Slănicul de Jos. He earned support from Dositheos II of Jerusalem, and eventually Matei lost the village.[70] The Leurdeanus also sold their land in Câmpulung to Radu Toma Năsturel, who established a princely school on that location.[71]

Evading his pursuers, Leurdeanu reached Ghica's exile court at Vidin in Rumelia.[72] By April 1672, he had returned with the latter to Wallachia. Though untitled, he served on the Boyar Assembly, almost uninterruptedly, from April 1672 to June 1673.[73] He was again made Wallachian regent (or Ispravnic of the throne) in 1672 and again in 1673; on both occasions, Ghica was leading Wallachian troops participating in the Polish–Ottoman War.[74] During this interval, he reportedly ordered the arrest and torture of other Cantacuzino heirs, including the future Stolnic and historian Constantin II.[75]

In December 1673, as George Ducas replaced Ghica on the throne, Leurdeanu again fled to Transylvania. Nevertheless, Ducas sent for him, promising him and his partisans that "no harm would come to them, but rather that he would hold them in great esteem." The news was delivered to Stroe by Drăghici's son Pârvu Cantacuzino, their encounter being described by Gane as a "sit-down between dog and wolf".[76] Agreeing to return home, Stroe was Logothete from February 28 to March 28, and Vornic from April 29 to May 5, 1674.[77] He became regent, or Ispravnic, from May 11, 1675, and again in June–September 1677—this was the interval during which Ducas served as Cossack Hetman in Right-bank Ukraine.[78]

The truce between the two feuding parties was short-lived. Peace was broken once the Cantacuzinos framed Leurdeanu's friend Radu Dudescu for treason. Stroe took revenge by persuading Ducas to imprison Constantin II in 1676.[79] For a while in 1677, the Vornic was involved in a property dispute with the monks of Sfântul Ioan-Grecesc Church: Leurdeanu defended his right to draw water from Dâmbovița River while trespassing on church grounds. The conflict was finally settled by two other boyars, namely Radu Crețulescu and Vistier Vâlcu.[80] Sources show that in 1678 Stroe was no longer a regent in Bucharest: Ducas preferred a triumvirate of Caimacami, presided upon by Șerban Cantacuzino.[81] Possibly reverting to his status as a monk, Leurdeanu was last mentioned as being alive on March 15, 1678, and is known to have been dead by December 18, 1679.[82] He was buried at Sfântul Ioan-Grecesc.[83]

Legacy

Vornic Leurdeanu was certainly survived by two of his sons: Pitar Stroe II and a Hieromonk Ghenadie; Matei Golescu was last attested for having served as Comis in 1673.[84] One document from 1680 suggests that Stroe Sr may have also had a living daughter, married to Șerban Pârvu Cantacuzino, grandson of his enemy Drăghici.[85] Pitar Stroe reconciled with the Cantacuzinos and the Craiovești, serving three short terms as Wallachia's Caimacam under Constantin Brâncoveanu; his own son, Statie, married Ilinca, daughter of Stolnic Constantin II.[86] While Istratie had died childless, Matei Golescu's son, diplomat Radu Golescu, would play an important part in the Pruth River Campaign and the Turkish War of 1716; one of his daughters was matriarch of the modern Golescu family.[87] Stroe's eponymous estate of Leordeni was inherited by Stroe's great-granddaughter Safta, who married into the Crețulescu family. In the 19th century, it became the domain of doctor-politician Nicolae Crețulescu.[88]

In addition to his patronage of churches at Vieroși and Golești, Leurdeanu inaugurated work on the family manor in the latter village.[89] Unlike the latter, his home in Tabaci no longer exists, having been leveled to build CEC Palace.[90] Golești church preserved two silk stoles, donated by СTPOЄ ВЄΛЬ ВИСTIA ("Stroe the Great Treasurer") and his wife Vișa, and now displayed by the National Museum of Art of Romania.[91] Of the paintings commissioned by Leurdeanu, only one portrait of him and his family survives in a watercolor copy; the original was probably at Leordeni church. It shows Leurdeanu wearing a combination of Ottoman and Polish clothes, including the kontusz, and donning a chupryna hairdo.[92]

As noted by author Gheorghe Bengescu, the first generations of Romanian historians "have shown themselves to be more than harsh in depicting Stroe Leurdeanu, though he had always denied, including during his trial, any participation in the crime for which he stood accused."[93] The Cantacuzinos, who retained political prominence into the 20th century, cultivated Leurdeanu's image as an antagonist. His sentencing was the subject of a mural painting by Nicolae Vermont, commissioned in 1909 for the Cantacuzino Palace in Bucharest.[94]

Notes

- Novac, p. 214; Stoicescu, p. 204

- Stoicescu, pp. 204, 206

- Stoicescu, pp. 181, 204, 206

- Stoicescu, p. 203

- Stoicescu, p. 204

- Stoicescu, p. 203

- Stoicescu, pp. 204, 206

- Stoicescu, p. 206

- Stoicescu, pp. 170, 181, 186, 188, 203–204, 205. See also Bengescu, p. 14; Novac, p. 214

- Bengesco, p. 14

- Stoicescu, pp. 204, 205

- Stoicescu, pp. 204, 205. See also Turcu, p. 322

- Bengesco, p. 19; Stoicescu, p. 205

- Stoicescu, p. 204

- Anton Manea, p. 18

- Stoicescu, pp. 204, 206

- Stoicescu, p. 206

- Stoicescu, p. 205

- Stoicescu, p. 205. See also Bengesco, p. 17, 19

- Stoicescu, pp. 204, 205

- Gane, pp. 239–240; Novac, p. 214; Stoicescu, p. 207

- Stoicescu, p. 207

- Stoicescu, pp. 176, 204, 205. See also Novac, pp. 214–215

- Novac, pp. 214–215

- Gane, p. 240

- Stoicescu, pp. 206, 207

- Stoicescu, p. 207

- Stoicescu, pp. 204, 206

- Stoicescu, p. 204

- Stoicescu, p. 204

- Novac, p. 215

- Cernovodeanu & Vătămanu, pp. 36–37, 44; Novac, p. 215

- Cernovodeanu & Vătămanu, pp. 36–37

- Novac, p. 215

- Stoicescu, p. 204

- Stoicescu, p. 186

- Stoicescu, p. 204

- Rezachevici, p. 99

- Stoicescu, p. 204

- Stoicescu, p. 204

- Rezachevici, pp. 100–104; Stoicescu, p. 206

- Rezachevici, pp. 103–104

- Stoicescu, p. 204. See also Rezachevici, p. 110

- Stoicescu, pp. 135, 204. See also Gane, pp. 330–332; Novac, p. 215

- Rezachevici, pp. 105–106, 108, 114, 115, 116–117

- Gane, p. 331

- Rezachevici, pp. 106–107. See also Gane, pp. 330–332, 342–344

- Gane, pp. 331–332, 333

- Rezachevici, pp. 108, 111

- Gane, p. 333

- Gane, p. 332–333

- Gane, pp. 333–336; Novac, p. 215; Rezachevici, pp. 106, 108; Stoicescu, pp. 135–136, 204. See also Bengesco, pp. 15–17; Panaitescu, pp. 435–436, 448–449

- Rezachevici, pp. 106, 108

- Gane, p. 333

- Stoicescu, p. 137

- Rezachevici, p. 112

- Stoicescu, p. 204

- Stoicescu, p. 204

- Gane, p. 343

- Gane, pp. 343–344; Rezachevici, pp. 112–114

- Panaitescu, p. 448

- Stoicescu, p. 186

- Panaitescu, pp. 448–449, 463

- Bengesco, p. 15; Gane, pp. 344–345; Panaitescu, p. 436; Rezachevici, p. 114; Stoicescu, p. 204

- Bengesco, p. 15; Gane, pp. 344–345; Panaitescu, p. 436

- Gane, p. 345

- Gane, p. 345; Novac, p. 215

- Stoicescu, pp. 204–205, 206, 215. See also Bengesco, p. 15

- Rezachevici, p. 114

- Anton Manea, pp. 18–19

- Ioan N. Ionescu, "Școala Națională Domnească. Cea mai veche școală din Câmpulung", in Universul Literar, Issue 13/1916, pp. 4–5

- Stoicescu, p. 205. See also Gane, p. 346

- Stoicescu, p. 205

- Stoicescu, p. 205. See also Gane, p. 348

- Gane, pp. 346–348

- Gane, p. 367

- Stoicescu, p. 205. See also Rezachevici, p. 115

- Stoicescu, p. 205

- Gane, pp. 367–368

- Novac, p. 214

- Gane, pp. 368–369

- Stoicescu, pp. 205, 206

- Stoicescu, p. 205

- Stoicescu, pp. 186, 205, 207

- Stoicescu, pp. 143–144. See also Bengesco, p. 15; Gane, p. 331; Rezachevici, p. 105

- Stoicescu, pp. 207, 243–244

- Bengesco, pp. 19–27; Novac, pp. 215–217; Stoicescu, pp. 186–187, 206

- (in Romanian) "Nicolae Kretzulescu și moșia de la Leordeni", in Jurnal de Argeș, May 28, 2014

- Bengesco, pp. 15, 17; Soare & Drăgan Popescu, p. 468

- Soare & Drăgan Popescu, p. 468

- Turcu, pp. 322–325, 330

- Soare & Drăgan Popescu, pp. 468–469

- Bengesco, pp. 15–16

- (in Romanian) Narcis Dorin Ion, "Elitele și arhitectura rezidențială (IX). O plimbare prin Micul Trianon", in Ziarul Financiar, March 16, 2010

References

- Cristina Anton Manea, "Din nou despre Tudoran mare clucer din Aninoasa", in Muzeul Național, Vol. XX, 2008, pp. 11–21.

- Georges Bengesco, Une Famille de boyards lettrés roumains au dix-neuvième siècle. Les Golesco. Paris: Librairie Plon, 1921. OCLC 4525010

- Paul I. Cernovodeanu, Nicolae Vătămanu, "Tabacii din Bucureștii de sus în veacul al XVII-lea", in București. Materiale de Istorie și Muzeografie, Vol. XI, 1992, pp. 26–45.

- Constantin Gane, Trecute vieți de doamne și domnițe. Vol. I. Bucharest: Luceafărul S. A., [1932].

- Vasile Novac, "Goleștii în istoria Bucureștilor", in București. Materiale de Istorie și Muzeografie, Vol. IX, 1972, pp. 213–222.

- P. P. Panaitescu, Contribuții la istoria culturii românești. Bucharest: Editura Minerva, 1971. OCLC 432822509

- Constantin Rezachevici, "Fenomene de criză social-politică în Țara Românească în veacul al XVII-lea (Partea a II-a: a doua jumătate a secolului al XVII-lea)", in Studii și Materiale de Istorie Medie, Vol. XIV, 1996, pp. 85–117.

- Ancuța Elena Soare, Elena Drăgan Popescu, "Vestimentația laică din tablourile ctitorilor de biserici – o identitate a spațiului argeșean în secolul al XVII-lea", in Luminița Botoșineanu, Ofelia Ichim, Cecilia Maticiuc, Dinu Moscal, Elena Tamba (eds.), Tradiție/inovație – identitate/alteritate: paradigme în evoluția limbii și culturii române, pp. 467–474. Iași: Editura Universității Alexandru Ioan Cuza, 2013. ISBN 978-973-703-952-1

- N. Stoicescu, Dicționar al marilor dregători din Țara Românească și Moldova. Sec. XIV–XVII. Bucharest: Editura enciclopedică, 1971. OCLC 822954574

- Iolanda Turcu, "Muzeografia – domeniu al științelor conexe", in Sargetia. Acta Mvsei Devensis, Vol. XXXIII, 2005, pp. 311–333.