Stephen Andrew Lynch

Stephen Andrew Lynch (September 3, 1882 – October 4, 1969), known more commonly as S.A. Lynch, was an early motion picture industry pioneer.

Personal life

Lynch grew up in Asheville, North Carolina, the son of Stephen Scott Lynch, a Civil War veteran wounded in the Battle of Gettysburg, and Jane Susannah Butler Lynch. Lynch was raised in his family's Asheville grocery business. Lynch stood out in his youth as a football and baseball star (earning the nickname "Diamond Lynch"), and was coaching and managing professionally by his early 20s. Lynch served the head football and baseball coach at Maryville University in Maryville, Tennessee, from 1902 to 1903.[1] Lynch was married twice, first to Flora Camilla Posey, who obtained a divorce from Lynch in 1924, and later to Julia Dodd Adair, an Atlanta socialite, whom he married in 1925.

Motion picture industry career

Beginnings as a theater owner and Paramount distributor

In 1909, Lynch, fresh off a successful baseball season with the local Asheville team, bought a stake in and began managing one of the first movie theaters in Asheville.[2] From 1909 through the early nineteen teens, Lynch continued to acquire movie theaters at a prodigious rate. By the mid nineteen teens, Lynch had enough clout as a theater owner to obtain a 25-year exclusive right to distribute Paramount motion pictures in 11 southern states from W.W. Hodkinson, founder of the fledgling Paramount Pictures organization (which was initially a motion picture distribution rather than production company).[3] Through the remainder of the nineteen teens, Lynch continued acquiring theaters and distributing Paramount product throughout the South.

Involvement with Triangle Distributing Company

In 1917, Lynch, at the urging of his Paramount colleague Hodkinson, bought into the Triangle Distributing Company, the distribution arm of the Triangle Film Corporation organized by Harry and Roy Aitken. Triangle had, in a very short span of time, become arguably the preeminent movie studio. Triangle's strength lay with its three star directors, D. W. Griffith, Thomas Ince and Mack Sennett. Triangle films also featured the premier actors of the day, including Douglas Fairbanks, William S. Hart, and Norma Talmadge. The Aitkens spun off the distribution side of Triangle in an effort to raise additional capital. In the process, the Aitkens brought in Hodkinson, who brought in Lynch.

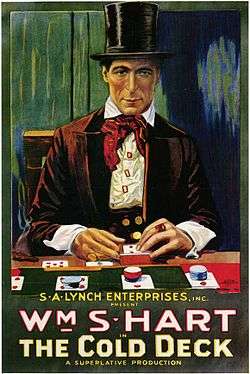

Lynch maintained a relatively low profile in his dealings with Paramount. However, with Triangle Distributing Company he branded certain Triangle output as "Distributed by S.A. Lynch Enterprises,"[4] perhaps the most notable example being "The Cold Deck," a 1917 Western starring William S. Hart the poster for which is still considered by some one of the all-time great movie posters.

Triangle Film Corporation began to fall apart in 1917 amidst financial scandals involving the Aitkins and lost its three 'star' directors and many of its star actors. Lynch, who by that time had had a falling out with Hodkinson and a third owner, Pawley, bought out both in order to obtain sole control of Triangle Distributing.[5] Even after Triangle Film Company had effectively dissolved, Lynch was able to make a profit with Triangle Distributing Company by re-cutting and releasing previously created (and sometimes previously released) Triangle Film Corporation output as new features, well into 1919.

Paramount's battle for the theaters

Almost from the beginning of the motion picture industry, W.W. Hodkinson and Paramount, in order to stabilize revenues and increase profits, implemented a subscription system for theaters known as "block booking" whereby a theater owner, if he wanted to show any Paramount pictures, would have to agree to take a block of Paramount product at a set price, sight unseen. Block booking was made possible for Paramount in part due to the exclusive contract between its principal supplier, the Famous Players Lasky Corporation and the first real motion picture star, the former "Biograph Girl," Mary Pickford. The public clamored for Mary Pickford's films, and theater owners felt compelled to obtain them.

Several major theater circuit owners, unhappy with Paramount's block booking arrangement, banded together in 1917 to form First National in order to create a competing stream of pictures for distribution to its members. First National quickly amassed a sufficient number of theaters under its umbrella to threaten the continued preeminence of Paramount. In order to prevent First National from pushing it out of the market, Paramount embarked upon a massive effort to obtain theaters to rival, if not crush, First National. The period of aggressive theater acquisition and competition between Paramount and First National has been dubbed by some as the "Battle for the Theaters."[6][7]

Rather than starting from scratch to amass theaters, Paramount turned to, among others, Lynch. Lynch, who was already a heavy Paramount shareholder having obtained Hodkinson's stock following his ouster in 1916 following the merger of Paramount into Famous Players Lasky,[3] convinced Paramount to form a new company with him, Southern Enterprises, Inc. The purpose of Southern Enterprises was to take over Lynch's exclusive distribution franchise and to acquire theaters in order to repel the First National challenge.[8] Although Southern Enterprises was owned half by Lynch and half by Paramount, Paramount was cash strapped due to other acquisitions and did not have money available to fund the new company. Not to be deterred, Lynch advanced Paramount's share of the Southern Enterprises capital on the condition that he remain in control until the loan was repaid.[9]

Southern Enterprises, seeking to break into markets controlled by First National, sent Lynch and his so-called "Wrecking Crew" or "Dynamite Gang" through the South to acquire theaters by whatever means necessary.[10][11] Testimony at Federal Trade Commission hearings related stories of Lynch and his gang arriving in a town served by a First National affiliated theater owner and offering to buy out the theater owner. If the theater owner refused, Lynch and his associates threatened to build a bigger, better theater across the street from the existing theater in order to put the theater owner out of business. The tactic worked, and the Dynamite Gang added continually to the Southern Enterprises theater chain.[12]

One principal target in the Battle for the Theaters was the Hulsey circuit in Texas and Oklahoma. Hulsey was one of the more prominent First National members, and Paramount felt obtaining the Hulsey circuit was one of the keys to breaking the threat First National posed. Lynch organized Southern Enterprises of Texas, Inc., capitalized by Paramount and its financial backers, and began buying up theaters throughout Texas and Oklahoma. Hulsey had been very successful with his theaters, but had reinvested his profits in theater expansion and leveraged his position with bank loans. As Lynch moved through Hulsey's territory purchasing theaters, a wire for $1 million arrived at Hulsey's bank for the credit of Southern Enterprises of Texas, Inc. Hulsey's banker called him in, and Hulsey promptly sold out to Paramount.[13][14] With the fall of Hulsey, and Paramount's infiltration of the First National board of directors through various theater chain acquisitions delivered in part by Lynch, First National crumbled as an effective competitor leaving Paramount the preeminent motion picture production and distribution company.

Ultimately, Lynch's tactics gave rise to controversy and disputes with Paramount. By that time, Paramount's financial position had improved and at the end of 1922 it negotiated a $5.7 million deal to pay off its debt to Lynch and acquire the Southern Enterprises theater chain, which then numbered in excess of 200.[15][16]

Federal Trade Commission antitrust charges

Lynch's activities during the Battle of the Theaters became front-page news in 1921 with the Federal Trade Commission's filing of an anti-trust suit against Lynch, Southern Enterprises, Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, Adolph Zukor, Jesse Lasky and several others.[17] The Federal Trade Commission charged that Lynch and the others had violated antitrust law by using oppression and coercion in the acquisition of theaters, utilizing the block booking method of distribution, and by forcing Paramount customers to exclude other producer's product from their screens.

As the public outrage over Paramount's practices subsided after the fall of First National, so did the government attorneys' encouragement to continue. After several years of prosecution, the case ultimately went away with the admonition that Paramount cease and desist its block booking practices for coercive uses, and permit individual theater owners to opt out of individual features for racial or religious opposition (but only after arbitration).[18][19]

Post-retirement involvement in the motion picture industry

Following the fall of First National as a rival to Paramount, and Lynch's sale of his Southern Enterprises, Inc. theater chain, Lynch retired to Miami Beach Florida in the early 1920s and assumed a more anonymous role with Paramount as a member of the Paramount Special Board.[20] Lynch was brought out of retirement during Paramount's 1933 bankruptcy to deal with its theater holdings.[21] Lynch later assumed control of Paramount's South Florida theater operations,[22] which he ran until 1945[20] when he retired for the second and final time from active involvement in the motion picture industry. One of Lynch's Southern Enterprises employees, Y. Frank Freeman[23] took over Lynch's daily activities with Paramount following his second retirement, and ultimately took over as President of Paramount following Adolph Zukor's tenure.

Career as a real estate developer

In the mid-1920s, flush from the Paramount buyout, Lynch turned his attention to real estate development. During the Florida land boom of the early 1920s, Lynch developed the Lynch Building, an office tower in Jacksonville, Florida which still bears his name, the Exchange Office Building in Miami, Florida, bought the Atlantan Hotel in Atlanta, Georgia, purchased and completed the unfinished Columbus Hotel in downtown Miami, Florida,[24] and purchased the Venetian and Towers Hotels, also in Miami.

Lindsey Hopkins Sr. also had an interest in the 17-story Columbus Hotel at Biscayne boulevard and N.E. First Street with S.A. Lynch.

Lynch also notably created the Sunset Islands,[25] a series of four man made islands in Biscayne Bay just north of the Venetian Islands, Star Island, Palm Island and Hibiscus Island.

Columbus Hotel controversy

Lynch's Columbus Hotel purchase proved controversial. Lynch purchased the partially finished hotel out of an involuntary bankruptcy proceeding commenced against the bond underwriter that had financed the hotel's construction. Following Lynch's purchase, the bondholder's committee, headed by George Emlen Roosevelt, a cousin of Theodore Roosevelt, brought suit against Lynch claiming they had been swindled. Lynch's actions were ultimately vindicated when he prevailed in the lawsuit. The presiding judge found that Lynch explicitly made no representations, and the bondholder's committee, which was represented by able and sophisticated businessmen, simply found that it had made a bad deal.[26] The Columbus Hotel remained in the Lynch family until the 1960s managed Lynch's son and grandson, S.A. Lynch, Jr. and Stephen A. Lynch, III. The Columbus was demolished in the 1980s and 50 Biscayne was constructed on the site in 2005.

Sunset Islands

The Sunset Islands were some of the last man-made islands created in Biscayne Bay. The Florida land boom of the 1920s ended in a catastrophic land bust just as Lynch finished filling the islands. Other developers were not able to withstand the bust; at least one partially completed man-made island project, Isola di Lolando was never completed. Lynch, however, had the resources to hold the Sunset Islands lots off the market and wait for conditions to improve. The islands remained landscaped but undeveloped until the 1930s, when the first lots went up for sale. Today the Sunset Islands remain one of the most exclusive and sought-after addresses in Miami Beach. Lynch himself built a residence on the southwest corner of Sunset II named "Sunshine Cottage," which was featured on tour-boat rides to see houses of the rich and famous.

Other business dealings

While Lynch's principal business was the motion picture industry, he had dealings as a major financier in many other industries over the course of his life. While most of these activities do not merit special mention, one in particular stands out as an example of the tenacity and aggression Lynch displayed in his business dealings. For several years during the early 1950s, Lynch waged a furious court battle in an effort to take over control of the Florida East Coast Railway, which was then in receivership. Lynch ultimately lost out to Ed Ball representing the DuPont family interests.[27]

Sports and recreation

As a young man, Lynch was a star athlete, excelling at both baseball and football. Lynch had a brief stint at Davidson College in 1903 as a coach and player for its baseball team, and later, in 1922, Lynch bought the minor league professional baseball team the Atlanta Crackers.[28]

Following his retirement from Paramount in the early 1920s, Lynch began his lifelong interest in yachting. In the mid-1920s, Lynch obtained Rival, one of several Sound Schooner class of 30-foot waterline racing yachts that competed in the waters off Long Island.[29] Lynch, on board Rival, was a competitor of Rod Stephens, father of the famous yacht designer Olin Stephens. Lynch also turned his attention to the houseboats built by the Mathis Yacht Building Company. Over the course of his life, Lynch owned three of these yachts, the 85-foot Jane, named for his daughter, the 105-foot Sunset, sister-ship to the USS Sequoia (presidential yacht) (launched on July 4, 1926, as Freedom, and renamed Freedom following a full restoration completed in 2008), and the 98-foot North Star.

References

- Maryville College: A History of 150 Years, 1819–1969. Maryville College. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- Asheville Citizen, October 3, 1909

- Hampton, Benjamin B., History of the American Film Industry, From its Beginnings to 1931, Copyright 1970, p. 254.

- Lahue, Kalton C., Dreams for Sale, The Rise and Fall of the Triangle Film Corporation, Copyright 1971, p. 171.

- Lahue, Kalton C., Dreams for Sale, The Rise and Fall of the Triangle Film Corporation, Copyright 1971, pp. 167-8.

- Hampton, Benjamin B., History of the American Film Industry, From its Beginnings to 1931, Copyright 1970, p. 252.

- Balio, Tino, "The American Film Industry", Copyright 1976, 1985 ed., p. 121.

- The Cravath Firm and its Predecessors, 1819-1947, v. 3, p. 363

- The Cravath Firm and its Predecessors, 1819-1947, v. 3, p. 363, n. 1

- Jobes, Gertrude, Motion Picture Empire, Copyright 1966, p. 219.

- Hampton, Benjamin B., History of the American Film Industry, From its Beginnings to 1931, Copyright 1970, p. 255.

- 1917–1919: Paramount, First National, and United Artists at the Wayback Machine (archived 8 July 2017)

- Jobes, Gertrude, Motion Picture Empire, Copyright 1966, p. 222.

- Hampton, Benjamin B., History of the American Film Industry, From its Beginnings to 1931, Copyright 1970, pp. 256-7.

- New York Times, January 7, 1923

- The Cravath Firm and its Predecessors, 1819-1947, v. 3, p. 363, n. 4

- New York Times, September 1, 1921.

- Hampton, Benjamin B., History of the American Film Industry, From its Beginnings to 1931, Copyright 1970, p. 368.

- New York Times, July 10, 1927.

- 1964 International Motion Picture Almanac, Quigley Publishing Company, p. 181

- New York Times, August 16, 1933.

- New York Times, July 24, 1936,

- Boxoffice Magazine, March 30, 1940, page 123.

- New York Times, Sept. 16, 1927

- Ballinger, Kenneth, Miami Millions, The Story of the 1925 Florida Land Boom and How it Turned into a Boomerang, 1936, p. 74

- Columbus Hotel Corp. et al. v. Hotel Management Co., 116 Fla. 464 (1934)

- In re Florida East Coast Ry. Co., 81 F.Supp. 926 (D.C.Fla. 1949)

- Atlanta Journal Constitution, September 14, 1922, p. 19

- New York Times, July 6, 1926