Stave church

A stave church is a medieval wooden Christian church building once common in north-western Europe. The name derives from the building's structure of post and lintel construction, a type of timber framing where the load-bearing ore-pine posts are called stafr in Old Norse (stav in modern Norwegian). Two related church building types also named for their structural elements, the post church and palisade church, are often called 'stave churches'.

Originally much more widespread, most of the surviving stave churches are in Norway. The only remaining medieval stave churches outside Norway are those of circa 1500 at Hedared in Sweden and one Norwegian stave church relocated in 1842 to contemporary Karpacz in the Karkonosze mountains of Poland. (One other church, the Anglo-Saxon Greensted Church in England, exhibits many similarities with a stave church but is generally considered a palisade church.)

Construction

Archaeological excavations have shown that stave churches, best represented today by the Borgund Stave Church, are descended from palisade constructions and from later churches with earth-bound posts.

Similar palisade constructions are known from buildings from the Viking Age. Logs were split in two-halves, set or rammed into the earth (generally called post in ground construction) and given a roof. This proved a simple but very strong form of construction. If set in gravel, the wall could last many decades, even centuries. An archaeological excavation in Lund uncovered the postholes of several such churches.

In post churches, the walls were supported by sills, leaving only the posts earth-bound. Such churches are easy to spot at archaeological sites as they leave very distinct holes where the posts were once placed. Occasionally some of the wood remains, making it possible to date the church more accurately using radiocarbon dating and/or with dendrochronology. Under the Urnes Stave Church, remains have been found of two such churches, with Christian graves discovered beneath the oldest church structure.

A single church of palisade construction has been discovered under the Hemse stave church.

The next design phase resulted from the observation that earthbound posts were susceptible to humidity, causing them to rot away over time. To prevent this, the posts were placed on top of large stones, significantly increasing their lifespans. The stave church in Røldal is believed to be of this type.

In still later churches, the posts were set on a raised sill frame resting on stone foundations. This is the stave church in its most mature form.

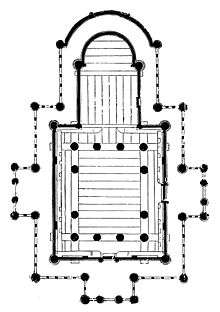

It is now common to group the churches into two categories: the first, without free-standing posts, often referred to as Type A; and the second, with a raised roof and free-standing internal posts, usually called Type B.

Those with the raised roof, Type B, are often further divided into two subgroups. The first of these, the Kaupanger group, have a whole arcade row of posts and intermediate posts along the sides and details that mimic stone capitals. These churches give an impression of a basilica.

The other subgroup is the Borgund group. In these churches the posts are connected halfway up with one or two horizontal double ″pincer beams″ with semicircular indentations, clasping the row of posts from both sides. Cross-braces are inserted between the posts and the upper and lower pincer beams (or above the single pincer beam), forming a very rigid interconnection, and resembling the triforium of stone basilicas. This design made it possible to omit the freestanding lower part of intermediate posts. In some churches in Valdres, only the four corner posts remain (see the image of Lomen Stave Church).

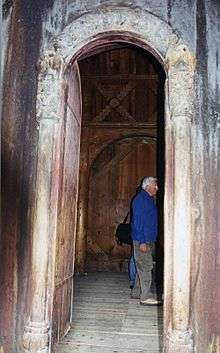

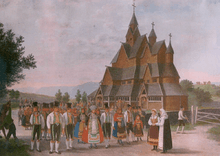

Many stave churches had or still have outer galleries or ambulatories around their whole perimeters, loosely connected to the plank walls. These probably served to protect the church from a harsh climate, and for processions.

Single nave church, Type A

At the base of Type A churches, there are four heavy sill beams on a low foundation of stones. These are interconnected in the corner notch, forming a rigid sill frame. The corner posts or staves (stavene in Norwegian) are cross-cut at the lower end and fit over the corner notches and cover them, protecting them from moisture.

On top of the sill beam is a groove into which the lower ends of the wall planks (veggtilene) fit. The last wall plank is wedge-shaped and rammed into place. When the wall is filled in with planks, the frame is completed by a wall plate (stavlægje) with a groove on the bottom, holding the top ends of the wall planks. The whole structure consists of frames – a sill frame resting on the stone foundation, and the four wall frames made up of sills, corner posts and wall plate.

The wall plates support the roof trusses, consisting of a pair of principal rafters and an additional pair of intersecting "scissor rafters". For lateral bracing, additional wooden brackets (bueknær) are inserted between the rafters.

Every piece is locked into position by other pieces, making for a very rigid construction; yet all points otherwise susceptible to the harsh weather are covered.

- The single nave church has a square nave and a narrower square choir. This type of stave church was common at the beginning of the 12th century.

- The long church, (Langkyrkje), has a rectangular plan with nave and choir of the same width. The nave will usually take up two-thirds of the whole length. This type was common at the end of the 13th century.

- The center post church, (Midtmastkyrkje) has a single central post reaching all the way up to and connected to the roof construction. But the roof is a simple hipped one, without the raised central part of the Type B churches. This variation on the common type of church, found in Numedal and Hallingdal, dates to around 1200.

Single nave churches in Norway: Grip, Haltdalen, Undredal, Hedal, Reinli, Eidsborg, Rollag, Uvdal, Nore, Høyjord, Røldal and Garmo.

The only remaining similar church in Sweden, in Hedared, is of this type and shows similarities with the one from Haltdalen.

Church with a raised roof, Type B

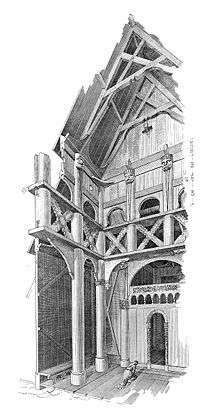

On the stone foundation, four huge ground beams (grunnstokker) are placed like a ⌗ sign, their ends protruding 1–2 meters from the lap joint where they intersect. The ends of these beams support the sills of the outer walls, forming a separate horizontal frame. The tall internal posts are placed on the internal frame of ground beams, and carry the main roof above the central nave (skip). On the outer frame of sills rest the main wall planks (veggtiler), carrying the roof over the pentice or aisles (omgang) surrounding the central space. The roof thus slopes down in two steps, as in a basilica.

The tall internal posts (staver) are interconnected with brackets (bueknær), and also connected to the outer walls with aisle rafters, creating a laterally rigid construction. Closer to the top of the posts (staver), shorter sills inserted between them support the upper wall (tilevegg). On top of the posts wall plates (stavlægjer) support the roof trusses, similar to those of the single nave churches.

The Kaupanger group consists of: Kaupanger, Urnes, Hopperstad and Lom.

The Borgund group consists of: Borgund, Gol, Hegge, Høre (Hurum), Lomen, Ringebu and Øye.

This form of a church can also be recognized from the holes which remain from earlier earth-bound post churches built on the same sites. Little is known about what these older churches actually looked like or how they were constructed, as they were all destroyed or replaced many centuries ago.

History

Stave churches were once common in northern Europe. In Norway alone, it was thought about 1000 were built; recent research has upped this number and it is now believed there may have been closer to 2000.[1]

Norway

Most of the surviving stave churches in Norway were built 1150–1350.[2] Stave churches older than the 1100s are known only from written sources or from archaeological excavations, but written sources are sparse and difficult to interpret.[3] Only 271 masonry churches were constructed in Norway during the same period, 160 of these still exist, while in Sweden and Denmark there were 900 and 1800 masonry churches respectively.[4] Frostathing Law and Gulating law rules about "corner posts" shows that stave church was the standard church building in Norway, even if the catholic church preferred stone.[5] All wooden churches in Norway before the reformation were constructed with staves. Log building is younger than stave building in Norway and was introduced in residential buildings around year 1000. Stave building is not influenced by the log technique.[6][7]

The word "stave church" is unknown in Old Norse, presumably because there were no other types of wooden churches. When Norway's churches after the Reformation were constructed in log, there was a need for a separate word for the older churches. In written sources from the Middle Ages, there is a clear distinction between "stafr" (posts) and "þili" or "vægþili" (wall boards). However, in documents from the 1600–1700s, "stave" was also used for wall boards or panels. Emil Eckhoff in his Svenska stavkyrkor (1914–1916) also included wood frame church buildings without posts.[8]

According to Norway's oldest written laws and Old Norwegian Homily Book, the consecration of the church was valid as long as the four corner posts were standing.[5] One of the sermons in the old homily book is known as the "stave church sermon". The sermon dates from around 1100 and was presumably performed at consecrations, or on the anniversary of such. The sermon text is a theological interpretation of the building elements in the church. It names most of the building elements in the stave church, and can be a source of terminology and technique.[9][10] For instance, the sermon says: "The four corner posts of the church are a symbol for the four gospels, because their teachings are the strongest supports within the whole of Christianity."[11]

Church building was mentioned in the Gulatingsloven (Gulating Law), which was written down in the 1000s. In the chapter on Christianity, the 12th article states:[12]

If one man builds a church, either lendmann does it or a farmer, or whoever builds a church, shall keep the church and the plot in good condition. But if the church breaks down and corner posts fall, then he shall bring timber to the plot before twelve months; if not, he will pay three marks in punishment to the bishop and bring timber and rebuild the church anyway.

(Um einskildmenn byggjer kyrkje, anten lendmann gjer det eller bonde, eller kven det er som byggjer kyrkje, skal han halda henne i stand og inkje øyda tufti. Men um kyrkja brotnar og hyrnestavane fell, då skal han føra timber på tufti innan tolv månadar; um det ikkje kjem, skal han bøta tre merker for det til biskopen og koma med timber og byggja opp kyrkja likevel."

In Norway, stave churches were gradually replaced; many survived until the 19th century when a substantial number were destroyed. Today, 28 historical stave churches remain standing in Norway. Stave churches were particularly common in less populated areas in high valleys and forest land, and fishermen's villages on islands and in minor villages along fjords. Around 1800 in Norway 322 stave churches were still known and most of these were in sparsely populated areas of Norway. If the main church was masonry the annex church could be a stave church.[5] Masonry churches were mostly built in towns, along the coast, and in rich agricultural areas in Trøndelag and East Norway, as well as in the larger parishes in fjord districts in Western Norway.[4] During 1400s and 1500s no new churches were built in Norway.[13] Norway's stave churches largely disappeared until 1700 and were replaced by log buildings. Several stave churches were redesigned or enlarged in a different technique during 1600–1700, for instance Flesberg Stave Church was converted into a cruciform church partly in log construction.[14] According to Dietrichson, most stave churches were dismantled to make room for a new church, partly because the old church had become too small for the congregation, partly because the stave church was in poor condition. Fire, storm, avalanche and decay were other reasons.[7] In 1650 there were about 270 stave churches left in Norway, and in the next hundred years 136 of these disappeared. Around 1800 there were still 95 stave churches, while over 200 former stave churches were still known by name or in written sources. From 1850 to 1885 32 stave churches fell, since then only the Fantoft Stave Church has been lost.[5]

Heddal stave church was the first stave church described in a scholarly publication when Johannes Flintoe wrote an essay in Samlinger til det Norske Folks Sprog og Historie (Christiania, 1834). The book also printed Flintoes drawings of the facade, the ground floor and the floor plan – the first known architectural drawing of a stave church.[15]

Other countries

It is unknown how many stave churches were constructed in Iceland and in other countries in Europe. Some believe they were the first type of church to be constructed in Scandinavia; however, the post churches are an older type, although the difference between the two is slight. A stave church has a lower construction set on a frame, whereas a post church has earth-bound posts.

In Sweden, the stave churches were considered obsolete in the Middle Ages and were replaced. In Denmark, traces of post churches have been found at several locations, and there are also parts still in existence from some of them. A plank of one such church was found in Jutland. The plank is now on display at the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen and an attempt at reconstructing the church is a featured display at the Moesgård Museum near Aarhus. Marks created by several old post churches have also been found at the old stone church in Jelling.

In Sweden, the medieval Hedared stave church was constructed c. 1500 at the same location as a previous stave church. Other notable places are Maria Minor church in Lund, with its traces of a post church with palisades, and some old parts of Hemse stave church on Gotland. In Skåne alone there were around 300 such churches when Adam of Bremen visited Denmark in the first half of the 11th century, but how many of those were stave churches or post churches is unknown.

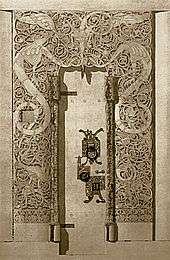

In England, there is one similar church of Saxon origin, with much debate as to whether it is a stave church or predates them. This is the Greensted Church in Essex. General consensus categorizes it as Saxon [Type A]. There is also another church which bears similarities to stave churches, the medieval stone church of St. Mary in Kilpeck in Herefordshire. It features a number of dragon heads.

In Germany, there is one stone church with a motif depicting a dragon similar to those often seen on Norwegian stave churches and on surviving artifacts from Denmark and Gotland. Whether this decoration can be attributed to cultural similarities or whether it indicates similar construction methods in Germany has sparked controversy.

During 1950–1970 post holes from older buildings were discovered under Lom stave church as well as under masonry churches such as Kinsarvik Church,[5] and this discovery was an important contribution to understanding the origin of stave churches. Holes for posts were first identified during excavations in Urnes stave church.[16]

Influences

Lorentz Dietrichson in his book De norske Stavkirker ("The Norwegian Stave Churches") (1892) claimed that the stave church is "a brilliant translation of the Romanesque basilica from stone to wood" ("En genial oversettelse fra sten til tre av den romanske basilika"). Dietrichson claimed that type B displays an influence from early Christian and Roman basilicas. The style was assumed to be transferred via Anglo-Saxon and Irish architecture, where only the particular roof construction was local. Dietrichson emphasized the clerestory, arcades and capitals.[7] The "basilica theory" was introduced by N. Nicolaysen in Mindesmærker af Middelalderens Kunst i Norge (1854). Nicolaysen wrote: "Our stave churches are now the only remaining of its kind, and according to the sparse records and known circumstances, it appears that nothing similar existed except perhaps in Britain and Ireland." ("Vore stavkirker er nu de eneste i sit slags, og saavidt sparsomme beretninger og andre omstændigheder lader formode, synes de heller ikke tidligere at have havt noget sidestykke med undtagelse af maaske i Storbritannien og Irland.")[17] Nicolaysen further claimed that the layout and design may have been inspired by Byzantine architecture. Nicolaysen wrote: "All facts suggest that the stave churches like the masonry churches and all medieval architecture in Western Europe originated from the Roman basilica." ("Alt synes at henpege paa, at forbilledet til vore stavkirker ligesom til stenkirkerne og overhovedet til hele den vesteuropæiske arkitektur i middelalderen er udgaaet fra den romerske basilika.")[18] This theory was further developed by Anders Bugge and Roar Hauglid. Peter Anker believed that the influence from foreign masonry architecture was primarily in decorative details.[19]

Per Jonas Nordhagen does not reject the basilica theory, but suggests development along two paths and that the basilical was a development towards larger and technically more sophisticated churches. The main, progressive path according to Nordhagen lead to Torpo and Borgund.[20]

Folklore and circumstantial evidence seem to suggest that stave churches were built upon old indigenous Norse worship sites, the hof. Dietrichson believed that the stave churches were closely connected to the hof and the "hof theory" attracted interest in the 1930–1940s. The theory assumed that the hofs were buildings with a square and a raised roof supported by four columns.[19] During Christianization of Norway local chiefs were forced to either dismantle the hofs or to convert hofs into churches. Bugge and Norberg-Schultz accordingly claimed that "there is no reason to believe that the last hofs and the first churches had any major differences" ("og da er det liten grunn til å tro at de siste hov har skilt seg synderlig fra de første kirker").[21] This assumption has been rejected by archeological evidence several times, in the case of Iceland by Åge Roussel.[22] Olaf Olsen described the hof merely as function related to ordinary buildings on major farms. If the hof was a particular building they remain to be identified, according to Olsen.[23] Olsen rejected the hof theory. Nicolay Nicolaysen also concluded that there is not a single case known of a hof that was converted to a church.[24]

Lack of historical evidence for hofs as buildings undermines the hof theory.[25] Nicolaysen also introduced the community centre hypothesis which argued that hofs were destroyed and churches constructed on the same convenient location for the local community. Location near a previous hof would then be a coincidence, according to Nicolaysen. Pope Gregory I encouraged (year 601) Augustine of Canterbury to reuse pre-Christian temples, but this had little relevance for Norway according to Nicolaysen. Jan Brendalsmo in his dissertation concluded that churches were often established on major farms or farms of local chiefs and close to feasting halls or graveyards.[26]

Stave churches appear to sometimes to have built upon or used materials from old pagan worship sites and are considered to be the best evidence for the existence of Norse Pagan temples and the best guide as to what they looked like.[27] The layout of the churches is believed to have mimicked old Pagan temples in design and was possibly designed in order to adhere to old Norse cosmological beliefs, especially as some churches were built around a central point like a world tree. Stave churches were also often located near or in the sight of large natural formations which also had a significant role in Norse Paganism, thus also suggesting a form of continuity through placement and symbolism.[28] Furthermore, dragons' heads and other clear mythological symbolism suggests the cultural blending of Norse mythological beliefs and Christianity in a non-contradictory synthesis. Owing to this evidence newer research has suggested that Christianity was introduced into Norway much earlier than was previously assumed.

Architecture and decoration

Even though the wooden churches had structural differences, they give a recognizable general impression. Formal differences may hide common features of their planning, while apparently similar buildings may turn out to have their structural elements organized completely differently. Despite this, certain basic principles must have been common to all types of building.

Basic geometrical figures, numbers that were easy to work with, one or just a few length units and simple ratios, and perhaps proportions as well were among the theoretical aids all builders inherited. The specialist was the man who knew a particular type of building so well that he could systematise its elements in a slightly different way from previous building designs, thus carrying developments a stage further.

"Exposing the timber frame on the interior and/or exterior of the structures is seen to release its matrix of timber members and its capacity to contribute architectural expression to buildings. The matrix, forming ‘lines’ in space, has an expressive potential that includes the capacity to delineate proportion, direct eye-movement, suggest spatial enclosure, create patterning, permit transparency and establish continuity with landscape."[29]

Dating of churches

Stave churches can be dated in various ways: by historical records or inscriptions, by stylistic means using construction details or ornaments, or by dendrochronology and radiocarbon dating. Often historical records or inscriptions will point to a year when the church is known to have existed. Archaeological excavations can yield finds which can provide relative dating for the structure, whereas absolute dating methods such as radiocarbon dating and dendrochronology can provide a more exact date. One drawback of dendrochronology is that it tends to overlook the possibility that the wood could have been reused from an older structure, or felled and left for many years before use.

A very important problem in dating the churches is that the solid ground sills are the construction elements most likely to have the outer parts of the log still preserved. Yet they are the most susceptible to humidity, and as people back then reused building parts, the church may have been rebuilt several times. If so, a dendrochronological dating may be based upon a log from a later reconstruction.

Old stave churches

Norway

A semi-official list of Norwegian stave churches which comply with specific criteria:

- Borgund Stave Church, Sogn og Fjordane – end of the 12th century

- Eidsborg Stave Church, Telemark – middle of the 13th century

- Flesberg Stave Church in Flesberg, Buskerud – c. 1200

- Fåvang Stave Church in Ringebu, Oppland – rebuilt in 1630 (two old churches rebuilt as one)

- Garmo Stave Church, Oppland – c. 1150

- Gol Stave Church in Gol (now at Norsk Folkemuseum, Oslo), Buskerud – 1212

- Grip Stave Church, Møre og Romsdal – second half of the 15th century

- Haltdalen Stave Church, Sør-Trøndelag – 1170–1179

- Hedal Stave Church, Oppland – second half of the 12th century

- Heddal Stave Church, Telemark – beginning of the 13th century

- Hegge Stave Church, Oppland – 1216

- Hopperstad Stave Church, Sogn og Fjordane – 1140

- Hylestad Stave Church, Setesdal – second half of the 12th century

- Høre Stave Church, Oppland – 1180

- Høyjord Stave Church, Andebu, Vestfold – second half of the 12th century

- Kaupanger Stave Church, Sogn og Fjordane – 1190

- Kvernes Stave Church, Møre og Romsdal – second half of the 14th century

- Lomen Stave Church, Oppland – 1179

- Lom Stave Church, Oppland – 1158

- Nore Stave Church, Nore og Uvdal, Buskerud – 1167

- Øye Stave Church, Oppland – second half of the 12th century

- Reinli Stave Church, Oppland – 1190

- Ringebu Stave Church, Oppland – first quarter of the 13th century

- Rollag Stave Church, Rollag, Buskerud – second half of the 12th century

- Rødven Stave Church, Møre og Romsdal – c. 1200

- Røldal Stave Church, Hordaland – first half of the 13th century (could be a post church)

- Torpo Stave Church, Ål, Buskerud – 1192

- Undredal Stave Church, Sogn og Fjordane – middle of the 12th century

- Urnes Stave Church, Sogn og Fjordane – first half of the 12th century (on UNESCO’s World Heritage Site)

- Uvdal Stave Church, Uvdal, Buskerud – 1168

Poland

- Vang Stave Church, moved to Poland (no longer on the official Norwegian list due to reconstruction)

Sweden

- Hedared stave church – c. 1500 on the site of an earlier stave church (not on the official Norwegian list)

- Hemse stave church – 11th century

England

- Greensted Church – 845 or 1053 (a church of Saxon origin sharing many construction details with stave churches)

Later stave churches and replicas

Stave churches are a very popular phenomenon and several have been built or rebuilt around the world. The two most copied are Borgund and Hedared, with some variations, and sometimes with adaptations to add elements from known stave churches from the area. In other places they are of a more free form and built for display.

Denmark

- Holmen Cemetery Chapel, Holmen Cemetery, Copenhagen, Denmark, built in 1902

- Hørning Stave Church, Moesgård Museum, Aarhus, reconstruction of an old church

Sweden

- Häggviks stave church, Mannaminne museum

- Lillsjöhögen Stave Church (2011)

- Skaga stave church, Töreboda, Västra Götaland County, built in the 12th century, torn down in the 19th century, rebuilt in the 1950s, burnt down, and rebuilt again in 2001

Iceland

- Heimaey stave church at Heimaey, Vestmannaeyjar, built 2000

US

- Boynton Chapel at Björklunden in Door County, Wisconsin

- Chapel in the Hills in Rapid City, South Dakota

- Hopperstad Stave Church (replica) at the Hjemkomst Center in Moorhead, Minnesota

- Little Norway, Wisconsin, relocated to Orkdal, Norway, in 2016

- Scandinavian Heritage Park in Minot, North Dakota.

- St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Islip, New York

- St. Swithun's in Warren County, Indiana.

- Washington Island Stavkirke on Washington Island, Wisconsin

- Norway Pavilion at Epcot, Walt Disney World Resort, near Orlando, Florida

Norway

- Fantoft Stave Church, built c. 1150, destroyed by arson in 1992 and rebuilt in 1997 (no longer on the official list)

- Gol Stave Church (replica), a replica erected in the 1990s at another (improbable) site in the community from which Gol Stave Church was translocated in the 1880s.

- Haltdalen Stave Church (replica), a copy of the old church, now at Sverresborg Museum

- Our Lady of Good Counsel Church, Porsgrunn, a Catholic Dragestil church built in 1899 that adheres closely to stave church design

- St. Olaf's Church, Balestrand, an Anglican Church, built in Dragestil, from 1897. A stave church imitation

Germany

- Gustav Adolf Stave Church in Hahnenklee, Harz region, Germany

Archaeological sites and dismantled churches

Iceland

- Þórarinsstaðir archaeological excavation in Seyðisfjörður, east Iceland (Post church which predates stave church)

Norway

- Hakastein Church, Skien. Archaeological excavation of post church constructed between 1010 and 1040.

- St. Thomas Church, Filefjell

- Vågå Stave Church (Portal from an old church)

Sweden

- Maria Minor church in Lund built around 1060

See also

- List of archaeological sites and dismantled stave churches

- Wooden Churches of Maramureș – Transylvanian churches of similar character

- Painted Churches in the Troödos Region – wooden-roofed medieval churches in Cyprus

- Kizhi – the open-air museum of Russian wooden architecture

- Medieval Scandinavian architecture

- Architecture of Norway

- Norway (Epcot)

- Chilotan architecture and Churches of Chiloé

- Heathen hof

References

Literature

- Directorate for Cultural Heritage, Stave Churches

- Anker, Peter (1997). Stavkirkene: Deres egenart og historie (in Norwegian). Oslo: J.W. Cappelens forlag. ISBN 978-82-02-15978-8.

- Lindgren, Mereth; Lydberg, Louise; Sandstrøm, Birgitta; Waklberg, Anna Greta (2002). Svensk Konsthistoria (in Swedish). Kristianstad. ISBN 978-91-85330-72-0.

- Bugge, Gunnar; Mezzanotte, Bernardino (1993). Stavkirker (in Norwegian). Oslo: Grøndahl og Dreyer. ISBN 978-82-504-2072-4.

- Bugge, Gunnar (1981). Stavkirkene i Norge (in Norwegian). Oslo: Dreyer. ISBN 978-82-09-01890-3.

- Hoftun, Oddgeir (2002). Stavkirkene – og det norske middelaldersamfunnet (in Norwegian). Copenhagen. ISBN 978-87-21-01977-8.

- Hoftun, Oddgeir (2003). Stabkirchen – und die mittelalterliche Gesellschaft Norwegens (in German). Köln: Verlag der Buchhandlung König. ISBN 978-3-88375-675-2.

- Hoftun, Oddgeir (2008). Kristningsprosessens og herskermaktens ikonografi i nordisk middelalder (in Norwegian). Oslo: Solum. ISBN 978-82-560-1619-8.

- Hohler, Erla Bergendahl (1999). Norwegian Stave Church Sculpture. 1–2. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press. ISBN 978-82-00-12748-2.

- Lagerlöf, Erland; Svahnström, Gunnar (1991). Gotlands Kyrkor (in Swedish). Kristianstad: R&S. ISBN 978-91-29-61598-2.

- Elstad, Hallgeir (2002). "Dei norske stavkyrkjene – ei innføring". Faculty of Theology, University of Oslo, curriculum. Archived from the original on 11 November 2005. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hauglid, Roar, Norske Stavkirker, Oslo 1973, multipart work

- Note that Roar Hauglid is a prolific author and the listed title is just one of several. Other books by him include: Norwegische Stabkirchen, Oslo 1970, ISBN 82-09-00938-9 and Norwegian stave churches, Oslo 1970

Footnotes

- "Verdifulle stavkirker : Riksantikvaren". Riksantikvaren.no. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- Storsletten, Ola (1993). En arv i tre: de norske stavkirkene. Oslo: Aschehoug. ISBN 8203220061.

- Anker, Leif: Middelalder i tre, Stavkirker, ARFO forlag 2005, ISBN 82-91399-16-6 (Kirker i Norge; bind 4)

- Ekroll, Øystein (1997): Med kleber og kalk. Norsk steinbygging i mellomalderen. Oslo: Samlaget.

- Anker, Peter (1997): Stavkirkene – deres egenart og historie. Oslo: Cappelen.

- Bugge and Mezzanotte, 1994, p. 17.

- Dietrichson, L. (1892). De norske stavkirker: studier over deres system, oprindelse og historiske udvikling : et bidrag til Norges middelalderske bygningskunsts historie. Kristiania: Cammermeyer.

- Gjærder, Per (1999). Stolper og staver i bygningsteknisk sammenheng. Grindbygde hus i Vest-Norge. NIKU-seminar om grindbygde hus, Bryggens museum 23.-25.03 1998. Edited by Helge Schjelderup and Ola Storsletten. Oslo: Norsk institutt for kulturminneforskning.

- Storsletten, Ola (1993). Takverk i steinkirker fra middelalderen. Oslo: Program for forskning om kulturminnevern, Norges forskningsråd. ISBN 8212001040.

- Ágústsson, Hördur 1976: "Kyrkjehus i ei norrøn homilie". By og Bygd, vol. XXV, 1–38; according to Jørgen H. Jensenius "Stavkirkeprekenen som bygningshistorisk kilde" I: Fortidsminneforeningens årbok, 2001.

- Gammelnorsk homiliebok. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1971, p. 102.

- Gulatingslovi. Oslo: Samlaget. 1952

- Vreim, Halvor (1947): Norsk trearkitektur. Oslo: Gyldendal.

- Muri, Sigurd: Gamle kyrkjer i ny tid. Oslo: Samlaget, 1975, s. 14.

- Bugge, Anders (1954). Heddal stavkirke. Oslo: Grøndahl.

- Christie, Håkon: Urnes stavkirkes forløper belyst ved utgravninger under kirken, Foreningen til norske Fortidsminnesmerkers bevaring, Årbok 1958, vol. 113, pp. 49–74

- Dietrichson (1892) p. 82

- Dietrichson (1892) p, 83

- Peter Anker (1997) Stavkirkene: deres egenart og historie. Oslo: Cappelen. ISBN 8202159784.

- Nordhagen, Per Jonas, "Stavkyrkjene" in Norsk arkitekturhistorie: frå steinalder og bronsealder til det 21. hundreåret. Oslo: Samlaget 2003, ISBN 82-521-5748-3, pp. 89–119

- Bugge og Norgberg-Schultz, 1994, s. 35.

- Aage Roussel, Islands gudehove, Stenberger 1943, side 215-223

- Olaf Olsen, Hørg, hov og kirke

- Jensenius, Jørgen H. (2001): Trekirkene før stavkirkene. Avhandling dr.ing. [PhD-dissertation], Arkitekthøyskolen i Oslo, 2001.

- Nordhagen 2003

- Hansen, Margareth (2014). Fire kirkesteder i Romsdal. Bergen: Universitetet i Bergen.

- Davidson, H. R. Ellis. 1988. Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe : Early Scandinavian and Celtic Religions. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

- Reed, Michael F. "Norwegian Stave Churches and Their Pagan Antecedents." RACAR: Revue D'art Canadienne / Canadian Art Review 24, no. 2 (1997): 3–13

- The Expressive Capacity of the Timber Frame by Brit Andresen. School of Geography, Planning and Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, Physical Sciences and Architecture, University of Queensland, QLD 4072, Australia. http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/ocs/index.php/AASA/2007/paper/viewFile/54/7. Retrieved 2 November 2013

External links

| Look up stave church in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stave churches. |