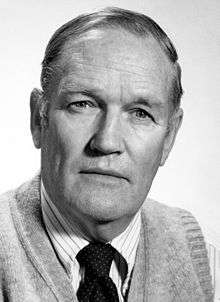

Stanley John Olsen

Stanley John Olsen (24 June 1919 – 23 December 2003) was an American vertebrate paleontologist and one of the founding figures of zooarchaeology in the United States. Olsen was also recognized as an historical archaeologist and scholar of United States military insignia, especially buttons of the American Colonial through Civil War periods. He was the father of John W. Olsen.

Early life and military service

Stanley Olsen was born in Akron, Ohio to John Mons Olsen (of Bergen, Norway) and Louise Marquardt (of Akron), the second of two sons.

After his graduation from high school in 1938, Olsen worked as a tool and die maker at the National Rubber Machinery Company in Akron until his marriage to Eleanor Louise Vinez (1917-2016) in 1942. He subsequently enlisted in the United States Navy, achieving the rank of Machinist Mate First Class while serving aboard the USS Mertz, Bunker Hill and Wyoming, and at naval bases on the U.S. East Coast and at Mare Island Navy Yard, California during the Second World War.

Career and scholarly contributions

Following his Honorable Discharge from the U.S. Navy in November 1945, Olsen found employment as a fossil preparator in the vertebrate paleontological laboratory of Alfred Sherwood Romer in the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University. Olsen's technical work as a preparator quickly evolved into his assignment as one of Professor Romer's two principal field supervisors. This opportunity led Olsen to the eastern coast of Canada where he prospected for Devonian fish fossils in Newfoundland and to the southeastern and western U.S. where he collected Tertiary fossils in Florida, Wyoming, and Montana and Permian and Triassic vertebrates in Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and Utah.

Herman Gunter's 1956 invitation to join the staff of the Florida Geological Survey in Tallahassee as State Vertebrate Paleontologist signaled the beginning of Olsen's scholarly career.

One of Olsen's first tasks was reopening excavations at the Thomas Farm site in Gilchrist County, Florida. The Thomas Farm locality, discovered in 1931, has produced the best known early Miocene terrestrial vertebrate fauna east of the U.S. Rocky Mountains. This unique site records predator-prey interactions of the coyote-like Metatomarctus and the ancestral horse, Parahippus, as well as a host of other species, on the margins of an 18-million-year-old wooded sinkhole and cave complex. Tens of thousands of fossils have been uncovered during more than 70 years of research at the site, ranging from frogs and bats to rhinoceroses and bears. Olsen's work on the Thomas Farm Caninae (dog-like carnivores, including Metatomarctus and the bear-dog, Amphicyon, and their kin) in the late 1950s and early 1960s is regarded as foundational for subsequent studies of those and related species. Olsen's analysis of the Thomas Farm carnivores not only established him as a vertebrate paleontologist, but also put him in contact with like-minded scholars the world over, including China, where he nurtured contacts that ultimately came to fruition during his many research trips there beginning in 1976.

In 1963, the renowned ornithologist Pierce Brodkorb honored Olsen's work by naming the first fossil stork described from the Tertiary of North America after him. The holotype of the ciconiid, Propelargus olseni, is a partial left tarsometatarsus discovered by Olsen in August 1961 in Middle Hemingfordian Torreya Formation deposits near Tallahassee and is now in the Florida Museum of Natural History's Pierce Brodkorb Ornithology Collection (catalog number 8504).

During his tenure at the Florida Geological Survey, Olsen helped pioneer the use of both SCUBA and helmeted diving equipment to explore the rich underwater fossil deposits of central and north Florida's rivers and springs. His work with colleagues in the Ichetucknee, Aucilla, and Wacissa rivers and in Wakulla Springs is especially well known because remains of mammoths and mastodons were found in association with bone and stone artifacts of human manufacture.[1]

His familiarity with SCUBA and a developing interest in the archaeology of the Colonial period United States led to Olsen's appointment by Governor Ferris Bryant as Director of Florida's Marine Salvage Committee in 1964. The natural conflicts between scientific inquiry and economic gain were poised to play out in 1960s Florida on a massive scale. The Gulf and Atlantic coasts’ abundant shipwrecks were only beginning to be recognized as a resource for both scientific study and financial exploitation and the Salvage Committee's challenge was to initiate accommodation between these two potentially antithetical goals. Olsen's work on the Salvage Committee was tangentially responsible for kindling his interest in Colonial European exploitation of domestic animals, a research focus that proved lifelong and best exemplified by his innovative analysis of faunal remains recovered from the Spanish ship Nuestra Señora de Atocha.

While on the staff of the F.G.S., Olsen also began to publish his widely distributed and highly respected comparative osteological manuals for archaeologists. These monographs of the Peabody Museum at Harvard signaled his conscious movement away from a focus on Tertiary paleontological assemblages toward Quaternary and Holocene bone accumulations associated with archaeological sites. Under Barbara Lawrence's influence during his frequent research trips to Harvard in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Olsen began to work more and more closely with archaeologists in their then fledgling attempts to incorporate the analysis and interpretation of animal remains from anthropogenic deposits into the body of traditional archaeological literature.

In 1968, Olsen accepted Hale G. Smith's invitation to join the faculty of the Department of Anthropology at Florida State University where he established one of the first zooarchaeology teaching laboratories in the country (along with those at Harvard University, the University of Tennessee, the Field Museum in Chicago, and the University of Florida). Olsen's transition from the mainly research-oriented environments of museums and the Florida Geological Survey to a broader spectrum academic career is especially noteworthy because he accomplished that feat holding only a high school diploma. Olsen joined the Florida State faculty as a tenured associate professor and was promoted to Full Professor in 1972.

In 1973, Olsen accepted the concurrent positions of Professor of Anthropology at the University of Arizona and Curator of Zooarchaeology in the Arizona State Museum in Tucson, which he held until his retirement in 1997.

While in Arizona, Olsen focused his work on elucidating evidence for the domestication of a number of vertebrate species, especially the dog, camel, and yak.

During his half-century professional career, Olsen conducted paleontological and zooarchaeological fieldwork in the U.S., Canada, Colombia, Belize, China, Tibet, India, Italy, Cyprus, and Nepal and worked extensively with museum collections in Great Britain, Russia, Egypt, and Sweden as well as the United States.

The Arizona State Museum's comparative vertebrate skeletal collections are housed in the Stanley J. Olsen Laboratory of Zooarchaeology, and the Stanley J. Olsen Zooarchaeology Endowment Fund was created at the University of Arizona in 2004 to recognize his contributions to the field.

Memberships and scholarly service

Stanley Olsen was a member of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, the Society for American Archaeology, the Society of the Sigma Xi, the Society of Mammalogists, and the American Society of Systematic Zoologists. He was a Fellow of both the Explorers Club and the Company of Military Historians. He served as the 26th President of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in 1965-1966 and was elected an Honorary Member in 1996 (the 50th anniversary of his joining the Society) in recognition of Olsen's distinguished contributions to the discipline of vertebrate paleontology.

Selected publications

- 1956 "The Caninae of the Thomas Farm Miocene", Breviora 66: 1-12, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University.

- 1958 "The fossil carnivore Amphicyon intermedius from the Thomas Farm Miocene, Part 1, Skull and Dentition", Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University 116(4): 157-172.

- 1959 "Fossil mammals of Florida", Florida Geological Survey Special Publication Number 6, Tallahassee.

- 1960 "Postcranial skeletal characters of Bison and Bos", Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University 35(4).

- 1964 "Mammal remains from archaeological sites, Part I, Southeastern and Southwestern United States", Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University 56(1).

- 1968 "Fish, amphibian, and reptile remains from archaeological sites, Part I, Southeastern and Southwestern United States", Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University 56(2).

- 1972 "Osteology for the archaeologist, 3, the American mastodon and woolly mammoth", Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University 56(3).

- 1972 "Osteology for the archaeologist, 4, North American birds", Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University 56(4).

- 1985 Origins of the Domestic Dog. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- 1990 "Fossil ancestry of the yak, its cultural significance, and domestication in Tibet", Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 142: 73-100.

- 1994 "The Asian elephant, Elephas maximus, and Chinese culture", Explorer’s Journal 72(1): 30-35.

References

- Gerrell, Philip R (1987). "The history and future of archaeological and paleontological work at Wakulla Springs (8WA24)". In: Mitchell, CT (eds.) Diving for Science 86. Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences Sixth Annual Scientific Diving Symposium. Held October 31 - November 3, 1986 in Tallahassee, Florida, USA. American Academy of Underwater Sciences. Retrieved 2011-01-19.