Standard gravitational parameter

In celestial mechanics, the standard gravitational parameter μ of a celestial body is the product of the gravitational constant G and the mass M of the body.

| Body | μ [m3 s−2] |

|---|---|

| Sun | 1.32712440018(9)×1020[1] |

| Mercury | 2.2032(9)×1013[2] |

| Venus | 3.24859(9)×1014 |

| Earth | 3.986004418(8)×1014[3] |

| Moon | 4.9048695(9)×1012 |

| Mars | 4.282837(2)×1013[4] |

| Ceres | 6.26325×1010[5][6][7] |

| Jupiter | 1.26686534(9)×1017 |

| Saturn | 3.7931187(9)×1016 |

| Uranus | 5.793939(9)×1015[8] |

| Neptune | 6.836529(9)×1015 |

| Pluto | 8.71(9)×1011[9] |

| Eris | 1.108(9)×1012[10] |

For several objects in the Solar System, the value of μ is known to greater accuracy than either G or M.[11] The SI units of the standard gravitational parameter are m3 s−2. However, units of km3 s−2 are frequently used in the scientific literature and in spacecraft navigation.

Definition

Small body orbiting a central body

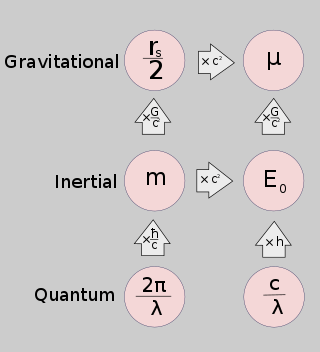

- The Schwarzschild radius (rs) represents the ability of mass to cause curvature in space and time.

- The standard gravitational parameter (μ) represents the ability of a massive body to exert Newtonian gravitational forces on other bodies.

- Inertial mass (m) represents the Newtonian response of mass to forces.

- Rest energy (E0) represents the ability of mass to be converted into other forms of energy.

- The Compton wavelength (λ) represents the quantum response of mass to local geometry.

The central body in an orbital system can be defined as the one whose mass (M) is much larger than the mass of the orbiting body (m), or M ≫ m. This approximation is standard for planets orbiting the Sun or most moons and greatly simplifies equations. Under Newton's law of universal gravitation, if the distance between the bodies is r, the force exerted on the smaller body is:

Thus only the product of G and M is needed to predict the motion of the smaller body. Conversely, measurements of the smaller body's orbit only provide information on the product, μ, not G and M separately. The gravitational constant, G, is difficult to measure with high accuracy,[12] while orbits, at least in the solar system, can be measured with great precision and used to determine μ with similar precision.

For a circular orbit around a central body:

where r is the orbit radius, v is the orbital speed, ω is the angular speed, and T is the orbital period.

This can be generalized for elliptic orbits:

where a is the semi-major axis, which is Kepler's third law.

For parabolic trajectories rv2 is constant and equal to 2μ. For elliptic and hyperbolic orbits μ = 2a|ε|, where ε is the specific orbital energy.

General case

In the more general case where the bodies need not be a large one and a small one, e.g. a binary star system, we define:

- the vector r is the position of one body relative to the other

- r, v, and in the case of an elliptic orbit, the semi-major axis a, are defined accordingly (hence r is the distance)

- μ = Gm1 + Gm2 = μ1 + μ2, where m1 and m2 are the masses of the two bodies.

Then:

- for circular orbits, rv2 = r3ω2 = 4π2r3/T2 = μ

- for elliptic orbits, 4π2a3/T2 = μ (with a expressed in AU; T in years and M the total mass relative to that of the Sun, we get a3/T2 = M)

- for parabolic trajectories, rv2 is constant and equal to 2μ

- for elliptic and hyperbolic orbits, μ is twice the semi-major axis times the negative of the specific orbital energy, where the latter is defined as the total energy of the system divided by the reduced mass.

In a pendulum

The standard gravitational parameter can be determined using a pendulum oscillating above the surface of a body as:[13]

where r is the radius of the gravitating body, L is the length of the pendulum, and T is the period of the pendulum (for the reason of the approximation see Pendulum in mathematics).

Solar system

Geocentric gravitational constant

GM⊕, the gravitational parameter for the Earth as the central body, is called the geocentric gravitational constant. It equals (3.986004418±0.000000008)×1014 m3 s−2.[3]

The value of this constant became important with the beginning of spaceflight in the 1950s, and great effort was expended to determine it as accurately as possible during the 1960s. Sagitov (1969) cites a range of values reported from 1960s high-precision measurements, with a relative uncertainty of the order of 10−6.[14]

During the 1970s to 1980s, the increasing number of artificial satellites in Earth orbit further facilitated high-precision measurements, and the relative uncertainty was decreased by another three orders of magnitude, to about 2×10−9 (1 in 500 million) as of 1992. Measurement involves observations of the distances from the satellite to Earth stations at different times, which can be obtained to high accuracy using radar or laser ranging.[15]

Heliocentric gravitational constant

GM☉, the gravitational parameter for the Sun as the central body, is called the heliocentric gravitational constant or geopotential of the Sun and equals (1.32712440042±0.0000000001)×1020 m3 s−2.[16]

The relative uncertainty in GM☉, cited at below 10−10 as of 2015, is smaller than the uncertainty in GM⊕ because GM☉ is derived from the ranging of interplanetary probes, and the absolute error of the distance measures to them is about the same as the earth satellite ranging measures, while the absolute distances involved are much bigger.

References

- "Astrodynamic Constants". NASA/JPL. 27 February 2009. Retrieved 27 July 2009.

- Anderson, John D.; Colombo, Giuseppe; Esposito, Pasquale B.; Lau, Eunice L.; Trager, Gayle B. (September 1987). "The mass, gravity field, and ephemeris of Mercury". Icarus. 71 (3): 337–349. Bibcode:1987Icar...71..337A. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(87)90033-9.

- "Numerical Standards for Fundamental Astronomy". maia.usno.navy.mil. IAU Working Group. Retrieved 31 October 2017., citing Ries, J. C., Eanes, R. J., Shum, C. K., and Watkins, M. M., 1992, "Progress in the Determination of the Gravitational Coefficient of the Earth," Geophys. Res. Lett., 19(6), pp. 529-531.

- "Mars Gravity Model 2011 (MGM2011)". Western Australian Geodesy Group. Archived from the original on 2013-04-10.

- "Asteroid Ceres P_constants (PcK) SPICE kernel file". Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- E.V. Pitjeva (2005). "High-Precision Ephemerides of Planets — EPM and Determination of Some Astronomical Constants" (PDF). Solar System Research. 39 (3): 176. Bibcode:2005SoSyR..39..176P. doi:10.1007/s11208-005-0033-2.

- D. T. Britt; D. Yeomans; K. Housen; G. Consolmagno (2002). "Asteroid density, porosity, and structure" (PDF). In W. Bottke; A. Cellino; P. Paolicchi; R.P. Binzel (eds.). Asteroids III. University of Arizona Press. p. 488.

- R.A. Jacobson; J.K. Campbell; A.H. Taylor; S.P. Synnott (1992). "The masses of Uranus and its major satellites from Voyager tracking data and Earth-based Uranian satellite data". Astronomical Journal. 103 (6): 2068–2078. Bibcode:1992AJ....103.2068J. doi:10.1086/116211.

- M.W. Buie; W.M. Grundy; E.F. Young; L.A. Young; et al. (2006). "Orbits and photometry of Pluto's satellites: Charon, S/2005 P1, and S/2005 P2". Astronomical Journal. 132 (1): 290–298. arXiv:astro-ph/0512491. Bibcode:2006AJ....132..290B. doi:10.1086/504422.

- M.E. Brown; E.L. Schaller (2007). "The Mass of Dwarf Planet Eris". Science. 316 (5831): 1586. Bibcode:2007Sci...316.1585B. doi:10.1126/science.1139415. PMID 17569855.

- This is mostly because μ can be measured by observational astronomy alone, as it has been for centuries. Decoupling it into G and M must be done by measuring the force of gravity in sensitive laboratory conditions, as first done in the Cavendish experiment.

- George T. Gillies (1997), "The Newtonian gravitational constant: recent measurements and related studies", Reports on Progress in Physics, 60 (2): 151–225, Bibcode:1997RPPh...60..151G, doi:10.1088/0034-4885/60/2/001. A lengthy, detailed review.

- Lewalle, Philippe; Dimino, Tony (2014), Measuring Earth's Gravitational Constant with a Pendulum (PDF), p. 1

- Sagitov, M. U., "Current Status of Determinations of the Gravitational Constant and the Mass of the Earth", Soviet Astronomy, Vol. 13 (1970), 712-718, translated from Astronomicheskii Zhurnal Vol. 46, No. 4 (July–August 1969), 907-915.

- Lerch, Francis J.; Laubscher, Roy E.; Klosko, Steven M.; Smith, David E.; Kolenkiewicz, Ronald; Putney, Barbara H.; Marsh, James G.; Brownd, Joseph E. (December 1978). "Determination of the geocentric gravitational constant from laser ranging on near-Earth satellites". Geophysical Research Letters. 5 (12): 1031–1034. Bibcode:1978GeoRL...5.1031L. doi:10.1029/GL005i012p01031.

- Pitjeva, E. V. (September 2015). "Determination of the Value of the Heliocentric Gravitational Constant from Modern Observations of Planets and Spacecraft". Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 44 (3): 031210. Bibcode:2015JPCRD..44c1210P. doi:10.1063/1.4921980.