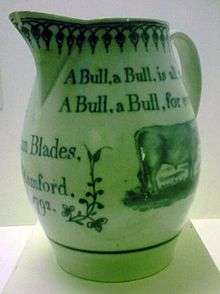

Stamford bull run

The Stamford bull run was a bull-running and bull-baiting event in the English town of Stamford, Lincolnshire. It was held on St Brice's Day (13 November), for perhaps more than 600 years, until 1839.[1] A 1996 Journal of Popular Culture paper refers to the bull run as a festival, in "the broader context of the medieval if not aboriginal festival calendar",[2] though works written during and shortly after the activity's later years variously describe it as a "riotous custom", a "hunt", an "old-fashioned, manly, English sport", an "ancient amusement", and – towards its end – an "illegal and disgraceful ... proceeding".[1][3]

Attempts to suppress the Stamford bull run began in 1788, the year the Tutbury bull run was brought to an end.[3] Other bull-running events had earlier been held in Axbridge, Canterbury, Wokingham and Wisbech.

Origins

Folklore in Stamford maintained that the tradition was begun by William de Warenne, 5th Earl of Surrey, during the reign of King John (1199—1216). The story, recorded by Richard Butcher in his The Survey and Antiquitie of Stamford Towne (1646), and described by Walsh as "patently fictional", relates how Warenne:

...was looking out of his castle window one 13 November and spied out on the meadow two bulls fighting over a cow. The Stamford butchers then came with their dogs to part the bulls, enraging them further and causing them to stampede through the town tossing about men, women and children. Earl Warenne joined the wild mêlée on horseback and so enjoyed himself that he gave to the butchers of Stamford that piece of mating ground, thereafter called "Bull-meadow", on condition that they replicate the event yearly thereafter.[4][lower-alpha 1]

The town of Stamford acquired common rights in the floodplain next to the River Welland, which until the last century was known as Bull-meadow, and today just as The Meadows.

The earliest documented instance of bull running appears in 1389, among guild records collected by Joshua Toulmin Smith. The document from Stamford's 'Gild of St Martin' states that "on the feast of St. Martin, this gild, by custom beyond reach of memory, has a bull; which bull is hunted by dogs, and then sold; whereupon the bretheren and sisteren sit down to feast."[5] The phrase "custom beyond reach of memory" leaves uncertain whether the custom pre-dated the guild (which was established by 1329).

The event

The ringing of St Mary's Church bells at 10.45 am opened the event, announcing the closing and boarding of shops and the barricading of the street with carts and wagons. By 11 am crowds gathered and the bull was released, baited by the cheering of the crowd, and (among other things) a man who would roll towards it in a barrel. It was then chased through the main street and down to Bull-meadow or into the River Welland. It was caught, killed and butchered. Its meat was provided to the poor and as such the custom by the 1700s was supported as a charity by donations.

Seventeenth-century historians described how the bull was chased and tormented for the day before being driven to Bull-meadow and slaughtered. "Its flesh [was] sold at a low rate to the people, who finished the day's amusement with a supper of bull-beef."[1]

Mabel Peacock noted that "a second bull was frequently subscribed for and run in some of the streets on the Monday after Christmas."[6]

Suppression

The event was a time of drunken disorder. The custom was periodically suppressed and eventually ended in the 19th century. The annual 15 August bull running in Tutbury, which was more violent and included mutilation of the bull, was ended by the Duke of Devonshire in 1788.[3] The same year, an unsuccessful attempt (the first recorded) was made to stop the Stamford event.[3]

The bull running in Stamford was the subject of an 1833 campaign by the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Some Stamford residents defended their ancient custom as a "traditional, manly, English sport; inspiring courage, agility and presence of mind under danger." Its defenders argued that it was less cruel and dangerous than fox hunting, and a local newspaper asked "Who or what is this London Society that, usurping the place of constituted authorities, presumes to interfere with our ancient amusement?"[1] A riot trial in 1836 tried only five men and convicted three; this inspired the town to plan a bigger event for the next year.[1] The mayor of Stamford – at the direction of and with the support of the Home Secretary – used 200 newly sworn-in special constables, some military troops, and police brought in from outside, to stop the bullrun of 1837, but it happened anyway. The bull and the people ran through the security line, a riot ensued, and in the end no one was killed (not even the bull, which turned out to have been supplied by or stolen from a local lord, discreetly unnamed in contemporary reports).[1]

The last bull run of Stamford was in 1839, in the face of an even larger force of soldiers and constables – some of the latter of whom smuggled the bull in themselves. The run was short, with the bull being captured by the peace-keeping forces quickly and without reported serious incident.[1] Because the townsfolk were forced to bear the cost of this militia presence for several years in a row, they agreed to stop the practice on their own henceforth, and kept their word.[1] The last known witness of the bull running was James Fuller Scholes who spoke of it in a newspaper interview in 1928 before his 94th birthday:[7]

I am the only Stamford man living who can remember the bull-running in the streets of the town. I can remember my mother showing me the bull and the horses and men and dogs that chased it. She kept the St Peter's Street – the building that was formerly the Chequers Inn at that time and she showed me the bull-running sport from a bedroom window. I was only four years old then, but I can clearly remember it all. The end of St Peter's Street (where it was joined by Rutland Terrace) was blocked by two farm wagons, and I saw the bull come to the end of the street and return again.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bull-running in Stamford. |

Notes and references

Notes

- Walsh writes of the story: "[T]he most this actually tells us is that Stamford's folk-imagination (if we can talk of such a thing) could not imagine anything earlier than the reign of King John."[5]

References

- Chambers, Robert (1864). "November 13. The Stamford Bull-running". Chambers Book of Days. The Book of Days: A Miscellany of Popular Antiquities in connection with the Calendar. II. W. & R. Chambers Ltd. p. 575. Retrieved 21 July 2018 – via Google Books.

- Walsh, Martin W. (Summer 1996). "November Bull-running in Stamford, Lincolnshire"" (PDF). Journal of Popular Culture. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1996.00233.x.

- Strutt, Joseph (1903) [1801]. "Performing Animals". In Cox, J. Charles (ed.). The Sports and Pastimes of the People of England: From the Earliest Period, Including the Rural and Domestic Recreations, May Games, Mummeries, Pageants, Processions and Pompous Spectacles (Enlarged and Corrected ed.). p. 209. Retrieved 21 July 2018 – via Google Books.

- Walsh 1996, p. 238.

- Walsh 1996, p. 240.

- Peacock 1904, pp. 200–201.

- "Stamford & District News (Closed 1942)". Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2014. Interview, 20 August 1928.

Bibliography

- Peacock, Mabel (1904), "Notes on the Stamford Bull-Running", Folklore, 15 (2): 199–202, doi:10.1080/0015587x.1904.9719402

- Walsh, Martin W. (1996), "November Bull-Running in Stamford, Lincolnshire" (PDF), The Journal of Popular Culture, 30 (1): 233–247, doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1996.00233.x, hdl:2027.42/73551