Stafford, Dolton

Stafford (anciently Stowford) is an historic manor in the parish of Dolton in Devon, England. The present manor house known as Stafford Barton is a grade II* listed building.[1] A house of some form has existed on the manor probably since the Norman Conquest in the 11th century. Surviving walls can be dated to the 16th century.[2] Many additions and renovations have taken place in the intervening years, and in the early 20th century Charles Luxmoore made many alterations and extensions and imported several major architectural features from ancient local mansions undergoing demolition so that "it has become somewhat difficult to discern its original form".[1] In the nineteenth century the estate was very substantial, with 400 acres of associated farmland and a large staff,[2] and by 1956, at the end of the Luxmoore tenure, it had grown to 1,460 acres with 7 farms, several cottages and smallholdings.[3]

History

Domesday Book

The Domesday Book of 1086 lists the manor of STAFORD as the first of the 7 manors or other landholdings held by Ansger of Montacute, one of the Devon Domesday Book tenants-in-chief of King William the Conqueror. It is not stated whether he held it in demesne of sub-infeudated it to his own tenant. The other manors and landholdings he held in Devonshire were: one virgate of land in Great Torrington; Brimblecombe; Cheldon; Muxbere; Sutton; Dolton.[4] His holdings later became the property of the feudal barony of Gloucester,[5] the Devonshire caput of which was Winkleigh. Ansgar is called elsewhere in Domesday Book "Ansgar of Senarpont", which manor is situated in the French department of Somme. He is apparently the same man as "Ansgar the Breton" who held other estates in Devon and Somerset from Robert, Count of Mortain,[6] half-brother of William the Conqueror, in Devon namely: Buckland Brewer, East Putford, Bulkworthy and Smytham.[7] Staford was in the historic Hundred of North Tawton.[8]

Kelloway/Stowford/Stafford

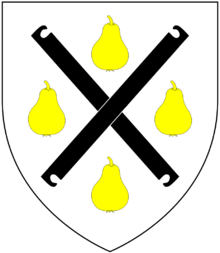

The manor was called "Stowford" during the mediaeval era, and was held for many generations by a gentry family of unknown origins named Kelloway (or Kellaway, etc.).[lower-alpha 1] The canting arms of this family display an ancient variety of pear from France called variously Caillou, Cailloel, Cailhou, etc.,[9] Anglicised as "Kelway pear". This is combined, for reasons unknown, with grozing irons, tools used by glaziers for cutting and shaping stained-glass panes. In the 16th century, for reason unknown, this family adopted the surname "Stowford" (later "Stafford") in place of "Kelloway",[10] but retained the arms of Kelloway.

The earliest dated member of the Kelloway family of Stafford is Thomas Kelloway (son of William Kelloway), who according to the Devon historian Tristram Risdon (d.1640) at "about the end of King Henry the third's reign" (1216–1272) gave the manor of Stafford to his younger son Philip Kelloway, together with the estate of "Edrescot". It is unclear where the senior line of the family resided thenceforth. In the 16th century a junior line became established in the neighbouring parish of Dowland and Hugh Stafford (1674–1734) of Dowland, a noted authority on cider and apple trees, purchased the manor of Upton Pyne near Exeter, where he built the grand Pynes House, surviving today, as his main residence. He left a daughter as his sole heiress who married into the Northcote family, bringing them several estates including Dowland and Iddesleigh. In 1852 the statesman Sir Stafford Northcote, 8th Baronet (whose first name is a reference to his Stafford ancestors and thus to the manor of Stafford) was ennobled by Queen Victoria as Earl of Iddesleigh. They remained at Pynes until the 1990s, when they sold it and moved to a new house nearby.[11]

Eliza Stafford, the last member of the Stafford family to occupy Stafford, died in 1887. Following financial difficulties the estate was sold by the Stafford family in 1889, and has belonged to a variety of individuals since then.[2]

Luxmoore

It was sold in 1912 to Charles Frederick Coryndon Luxmoore (1872–1933), FSA, FRGS, formerly a Captain in the 3rd Cheshire Regiment, and particularly noted as an explorer of the Amazon.

The Luxmoore family

Luxmoore's family was long established in Devon and is earliest recorded in the 16th century as seated at Morestone in the parish of Bratton Clovelly, Devon. The family is said to have originated "at a stretch of moorland" called Lukesmore in the parish of Lydford near Dartmoor.[12] His great-grandfather's second cousin was John Luxmoore (1766–1830), Bishop of Bristol, Bishop of Hereford and Bishop of St Asaph.[13] His ancestor John Luxmoore (1692–1750) of Witherdon and of Northmore House (now the Town Hall), Okehampton, was an Attorney-at-Law, the owner of Okehampton Castle and was the Assay-Master of Tin for the Duchy of Cornwall. Charles Frederick Coryndon Luxmoore was the son of Capt. Charles Luxmoore-Brooke (1824–1890), 37th Regiment of Foot, of Ashbrook Hall in Cheshire and of Witherdon, Broadwoodwidger and Germansweek in Devon, who was aide de camp to the Governor of Ceylon in 1855 and served in the Indian Mutiny of 1857. Luxmoore-Brooke had inherited the Cheshire estates of his maternal uncle Henry Brooke and in accordance with the terms of the bequest adopted by royal licence the additional surname of Brooke (which his son discontinued). In 1906 Charles Luxmoore purchased the manor of Witheridge in Devon, from Newton Wallop, 6th Earl of Portsmouth (1856–1917),[14] and in 1923 purchased Eggesford House, Devon, from his younger brother John Fellowes Wallop, 7th Earl of Portsmouth (1859–1925).[13] Luxmoore was Chairman of the Eggesford Foxhounds,[15] founded by the Earls of Portsmouth. He was a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society[15] and in 1928 was engaged in an expedition to the River Amazon,[16] during which he drew a map of that river and its tributaries. He was an art collector and antiquary, a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London[15] and was the author of Smallglaze (English Smallglaze Earthenware) With the Notes of a Collector (1924). He was the historian of the Luxmoore family, author of The Family of Luxmoore (1909).

Changes at Stafford Barton

Charles Luxmoore carried out substantial alterations to Stafford Barton, most notably the addition of a crenellated West Wing[2] in which he installed a very large decorative plaster ceiling of circa 1600, removed from an Elizabethan house in Barnstaple, and other architectural items taken from nearby recently demolished historic houses.[17] He also indulged a penchant for building secret panels and cupboards, discovered later on by subsequent owners (see below). From his explorations Luxmoore brought back tropical plants, which he grew in the mild Devon climate.[18] He kept a prestigious historical harpsichord made by the 18th century Italian builder Vincentio Sodi.[lower-alpha 4]

Luxmoore had a large family by his wife Rosalie Maud Acworth Ommanney, a grand-daughter of Henry Mortlock Ommanney (1816–1880), discoverer, surveyor and namesake of Mortlock River, Western Australia and relative of Admiral Sir John Acworth Ommanney (1773–1855) Commander-in-Chief, Plymouth.[19] Several of his sons had distinguished naval or military careers. The estate remained in the family until 1956.

Sale

On 23 August 1956 the "freehold sporting and agricultural property known as the Stafford Barton Estate" was offered for sale by direction of "the executors of the late Mrs R.M.A. Luxmoore". It included the "part 13th-century manor house of great charm" with six principal and six secondary bedrooms, four bathrooms, spacious panelled reception rooms, staff wing, excellent outbuildings" etc., with about 1,460 acres of land, seven "well-maintained" and "well-let" farms, several cottages and smallholdings with six miles of salmon and trout fishing on the River Taw, all producing an annual rent of £1,580. The auction took place at the Rougemont Hotel in Exeter on 28 September 1956.[3]

Croxton

The purchasers were a family by the name of Croxton, who also bought 126 acres for sheep farming. The Croxtons restored the gardens, and in the house they discovered a variety of false walls, concealed doors, and secret cupboards, some of which contained historical objects including a human skull dated from the mid 19th century. These amusements are believed by Haigh to have been the work of Charles Luxmoore, with the various objects obtained during his extensive explorations.[2]

The Croxton family stayed until 1965.[2]

Zuckermann

From 1969 Stafford Barton was owned and occupied by the German-American harpsichord builder Wolfgang Zuckermann, who had "run away from America".[20] He sold his harpsichord business and emigrated from the United States, where he had lived for many years in New York City. He continued to build harpsichords at Stafford, though hardly on his former quasi-industrial scale.

In 1971 Zuckermann reported in a letter to the New York weekly newspaper Village Voice that he had been able to buy Stafford for "no more than the average suburban one-family house in New Jersey". He also wrote that "the house [has] much old paneling and leaded lights (even my goats have leaded lights in their stable.)", and he said that the gardens were tended by a pensioner who "came with the property".[20] The date Zuckermann left Stafford Barton is unknown, but advertisements and directory entries for his harpsichord business list him there up to 1973.[21]

Doran

In 2007 Stafford Barton became the property of the Doran family, and the house and gardens have been extensively restored. This work was completed before 2015.[2]

Notes

- "Kelloway", spelling given in Vivian, p.510, pedigree of "Kelloway of Stowford". According to Haigh (2009), "it was the home to the Caillaway family (who gradually became Stofford and then Stafford) for over 700 years starting about 1150."[2]

- The BLG blazon gives a bordure nebuly sable charged with eight bezants, which (apart from the bezants) is not depicted in this image. Bordures bezantée generally indicate a connection with the Duchy of Cornwall, and Luxmoore's ancestor John Luxmoore (1692–1750) of Okehampton was the Assay-Master of Tin for the Duchy of Cornwall.

- Said by Pevsner, p.338, to have been no.7, Cross Street, possibly the town-house of the Dodderidge family of Barnstaple merchants which was demolished in 1902 to make way for a new Post Office (for information on this house see: Lamplugh, Lois, Barnstaple: Town on the Taw, South Molton, 2002, p.134). The ceiling is reminiscent of the contemporaneous surviving one in the Golden Lion Coaching Inn, Boutport Street (in 2016 "The Bank Restaurant"), which also displays Bourchier heraldry.

- Luxmoore's widow sold the instrument in 1934 and it is now in the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter and has recently been restored. See http://vincenzo.sound-gallery.net/sodi.html.

References

- Listed building text

- Haigh, Lesley (2009) "Stafford Barton, Dolton, Devon: A House with History".

- Advertisement by Connell's estate agent in Country Life magazine, 23 August 1956, Supplement, p.15. (Image in Ebay listing)

- Thorn, Caroline & Frank, (eds.) Domesday Book, (Morris, John, gen.ed.) Vol. 9, Devon, Parts 1 & 2, Phillimore Press, Chichester, 1985, 40,1-7

- Thorn & Thorn, part 2 (notes), chap.40

- Thorn & Thorn, part 2 (notes), chap.15, 12-13

- Thorn & Thorn, part 1, 15,12-15

- Thorn & Thorn, part 2 (notes), chap.40,1

- Piper, Bill. "Our family name, Heraldry and Pears".

- Vivian, p.510, footnote

- Lauder, Rosemary, Devon Families, Tiverton, 2002, p.113

- Burke's Landed Gentry, pp.1439–40, pedigree of "Luxmoore of Broadwoodwidger and Germansweek"

- Burke's Landed Gentry, p.1440

- Witheridge: "The Centuries in Words and Pictures", Appendix 1: The manor of Witheridge. (which erroneously states that Newton Fellowes, 4th Earl of Portsmouth (1772–1854) died in 1906)

- Burke's Landed Gentry, p.1439

- The National Archives. "Luxmoore Family".

- Cherry and Pevsner (2002:338)

- Zuckermann (1971:12)

- Burke's Landed Gentry, p.1439, with names confused

- Zuckermann, Wolfgang (1971) "Running away from america", The Village Voice, July 15, p. 11 et seq. On line here

- A directory entry can be found in Anonymous (1973) The Register of Early Instruments, Early Music Vol. 1, No. 3 (Jul., 1973), pp. 179-181+183+185-190.

- Sources

- Anonymous (2013) "Stafford Barton manor" webpage.

- Burke's Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry, 15th Edition, ed. Pirie-Gordon, H., London, 1937.

- Cherry, Bridget & Pevsner, Nikolaus, The Buildings of England: Devon. Yale University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-300-09596-8. Extracts at Google Books.

- Smith, Michael Townsend (n.d.) "Dream books". Blog entry.

- Thorn, Caroline & Frank, (eds.) Domesday Book Vol. 9: Devon, Parts 1 & 2, Phillimore Press, Chichester, 1985.

- Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitations of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620. Exeter, 1895.