Squarewave voltammetry

Squarewave voltammetry (SWV) is a form of linear potential sweep voltammetry that uses a combined square wave and staircase potential applied to a stationary electrode.[1] It has found numerous applications in various fields, including within medicinal and various sensing communities.

History

When first reported by Barker in 1957,[2] the working electrode utilized was primarily a dropping mercury electrode (DME). When using a DME, the surface area of the mercury drop is constantly changing throughout the course of the experiment; for this reason, complex mathematical modeling was at times required in order to analyze collected electrochemical data. The squarewave voltammetric technique allowed for the collection of the desired electrochemical data within one mercury drop, meaning that the need for mathematical modeling to account for the changing working electrode surface area was no longer needed. In short, the introduction and development of this technique allowed for the rapid collection of reliable and easily reproducible electrochemical data using DME or SDME working electrodes. With continued improvements from many electrochemists (particularly the Osteryoungs), SWV is now one of the primary voltammetric techniques available on modern potentiostats.[3]

Theory

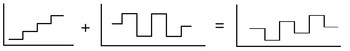

In a squarewave voltammetric experiment, the current at a (usually stationary) working electrode is measured while the potential between the working electrode and a reference electrode is swept linearly in time. The potential waveform can be viewed as a superposition of a regular squarewave onto an underlying staircase (see figure above); in this sense, SWV can be considered a modification of staircase voltammetry.

The current is sampled at two times - once at the end of the forward potential pulse and again at the end of the reverse potential pulse (in both cases immediately before the potential direction is reversed). As a result of this current sampling technique, the contribution to the current signal resulting from capacitive (sometimes referred to as non-faradaic or charging) current is minimal. As a result of having current sampling at two different instances per squarewave cycle, two current waveforms are collected - both have diagnostic value, and are therefore preserved. When viewed in isolation, the forward and reverse current waveforms mimic the appearance of a cyclic voltammogram (which corresponds to the anodic or cathodic halves, however, is dependent upon experimental conditions).

Despite both the forward and reverse current waveforms having diagnostic worth, it is almost always the case in SWV for the potentiostat software to plot a differential current waveform derived by subtracting the reverse current waveform from the forward current waveform. This differential curve is then plotted against the applied potential. Peaks in the differential current vs. applied potential plot are indicative of redox processes, and the magnitudes of the peaks in this plot are proportional to the concentrations of the various redox active species according to:

where Δip is the differential current peak value, A is the surface area of the electrode, C0* is the concentration of the species, D0 is the diffusivity of the species, tp is the pulse width, and ΔΨp is a dimensionless parameter which gauges the peak height in SWV relative to the limiting response in normal pulse voltammetry.[4]

Renewal of diffusion layer

It is important to note that in squarewave volammetric analyses, the diffusion layer is not renewed between potential cycles. Thus, it is not possible/accurate to view each cycle in isolation; the conditions present for each cycle is a complex diffusion layer which has evolved through all prior potential cycles. The conditions for a particular cycle are also a function of electrode kinetics, along with other electrochemical considerations.

Applications

Because of the minimal contributions from non-faradaic currents, the use of a differential current plot instead of separate forward and reverse current plots, and significant time evolution between potential reversal and current sampling, high sensitivity screening can be obtained utilizing SWV. For this reason, squarewave voltammetry has been utilized in numerous electrochemical measurements and can be viewed as an improvement to other electroanalytical techniques. For instance, SWV suppressed background currents much more effectively than cyclic voltammetry - for this reason, analyte concentrations on the nanomolar scale can be registered utilizing SWV over CV.

SWV analysis has been used recently in the development of a voltammetric catechol sensor,[5] in the analysis of a large number of pharmaceuticals,[6] and in the development and construction of a 2,4,6-TNT and 2,4-DNT sensor[7]

In addition to being utilized in independent analyses, SWV has also been coupled with other analytical techniques, including but not limited to thin-layer chromatography (TLC)[8] and high-pressure liquid chromatography.[9]

See also

- Voltammetry

- Electroanalytical method

References

- Ramaley, Louis.; Krause, Matthew S. (2002). "Theory of square wave voltammetry". Analytical Chemistry. 41 (11): 1362–1365. doi:10.1021/ac60280a005. ISSN 0003-2700.

- Barker, G. C., Congress on Analytical Chemistry in Industry, St Andrews, June 1957.

- F. Scholz (Ed.). Electroanalytical Methods: Guide to Experiments and Applications.

- Bard, A.J. and L.R. Faulkner. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications. 2nd Ed, 2001.

- Mersal, G. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 4(2009), 1167-1177.

- Dogan-Topal, B. et al. Open Chemical and Biomedical Methods Journal. 2010, 3, pp 56-73.

- Bozic, R.G., West, A.C., Levicky, R. Sensors and Actuators B. 133(2008), 509-515.

- Petrovic SC, Dewald HD. J. Planar Chromatography. 1996, 9:269.

- Hoekstra JC, Johnson DC. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1999, 390:45.