Spectral music

The spectral approach to musical composition was first given a name in 1979 by Hugues Dufourt, in an article he entitled "Musique spectrale" (Spectral music).[1] In spectral music, the spectrum – or group of spectra – replace harmony, melody, rhythm, orchestration and form. The spectrum is always in motion, and the composition is based on spectra developing through time and exerting an influence on rhythm and formal processes. Spectral music seeks to exteriorize the inner reality of sound, to project its inner dynamics into an acoustic space and time, and to transmit to the public the reality of sound in all its complexity.[2]

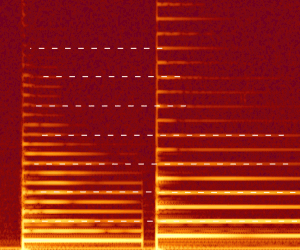

Defined in technical language, spectral music is an acoustic musical practice where compositional decisions are often informed by sonographic representations and mathematical analysis of sound spectra, or by mathematically generated spectra. The spectral approach focuses on manipulating the spectral features, interconnecting them, and transforming them. In this formulation, computer-based sound analysis and representations of audio signals are treated as being analogous to a timbral representation of sound.

The (acoustic-composition) spectral approach originated in France in the early 1970s, and techniques were developed, and later refined, primarily at IRCAM, Paris, with the Ensemble l'Itinéraire, by composers such as Gérard Grisey and Tristan Murail. Murail has described spectral music as an aesthetic rather than a style, not so much a set of techniques as an attitude; as Joshua Fineberg puts it, a recognition that "music is ultimately sound evolving in time".[3] Julian Anderson indicates that a number of major composers associated with spectralism consider the term inappropriate, misleading, and reductive.[4] The Istanbul Spectral Music Conference of 2003 suggested a redefinition of the term "spectral music" to encompass any music that foregrounds timbre as an important element of structure or language.[5]

Origins and history

While spectralism as a historical movement is generally considered to have begun in France and Germany in the 1970s, precursors to the philosophy and techniques of spectralism, as prizing the nature and properties of sound above all else as an organizing principle for music, go back at least to the early twentieth century. Proto-spectral composers include Claude Debussy, Edgard Varèse, Giacinto Scelsi, Olivier Messiaen, György Ligeti, Iannis Xenakis, LaMonte Young, and Karlheinz Stockhausen.[6] Other composers who anticipated spectralist ideas in their theoretical writings include Harry Partch, Henry Cowell, and Paul Hindemith.[7] Also crucial to the origins of spectralism was the development of techniques of sound analysis and synthesis in computer music and acoustics during this period, especially focused around IRCAM in France and Darmstadt in Germany.[8]

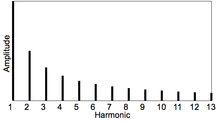

Julian Anderson considers Danish composer Per Nørgård's Voyage into the Golden Screen for chamber orchestra (1968) to be the first "properly instrumental piece of spectral composition".[9] Spectralism as a recognizable and unified movement, however, arose during the early 1970s, in part as a reaction against and alternative to the primarily pitch focused aesthetics of the serialism and post-serialism which was ascendant at the time.[10] Early spectral composers were centered in the cities of Paris and Cologne and associated with the composers of the Ensemble l'Itinéraire and the Feedback Group, respectively. In Paris, Gerard Grisey and Tristan Murail were the most prominent pioneers of spectral techniques; Grisey’s “Espaces Acoustiques” and Murail’s “Gondwana” were two influential works of this period. Their early work emphasized the use of the overtone series, techniques of spectral analysis and ring and frequency modulation, and slowly unfolding processes to create music which gave a new attention to timbre and texture.[11]

The German Feedback Group, including Johannes Fritsch, Mesias Maiguashca, Peter Eötvös, Claude Vivier, and Clarence Barlow, was primarily associated with students and disciples of Karlheinz Stockhausen, and began to pioneer spectral techniques around the same time. Their work generally placed more emphasis on linear and melodic writing within a spectral context as compared to that of their French contemporaries, though with significant variations.[12] Another important group of early spectral composers was centered in Romania, where a unique form of spectralism arose, in part inspired by Romanian folk music.[13] This folk tradition, as collected by Béla Bartók (1904–1918), with its acoustic scales derived directly from resonance and natural wind instruments like "buciume", "tulnice", and "cimpoi" inspired several spectral composers: Anatol Vieru, Aurel Stroe, Ştefan Niculescu, Horațiu Rădulescu, Iancu Dumitrescu, and Octavian Nemescu.[14]

Towards the end of the twentieth century, techniques associated with spectralist composers began to be adopted more widely and the original pioneers of spectralism began to integrate their techniques more fully with those of other traditions. For example, in their works from the later 1980s and into the 1990s, both Grisey and Murail began to shift their emphasis away from the more gradual and regular process which characterized their early work to include more sudden dramatic contrasts as more well linear and contrapuntal writing.[15] Likewise, spectral techniques were adopted by composers from a wider variety of traditions and counties, including the UK (with composers like Julian Anderson and Jonathan Harvey), Finland (composers like Magnus Lindberg and Kaija Saariaho), and the United States.[16] A further development is the emergence of "hyper-spectralism" in the works of Iancu Dumitrescu and Ana-Maria Avram.[17]

Compositional technique

"The spectral adventure has allowed the renovation, without imitation of the foundations of occidental music, because it is not a closed technique but an attitude." – Gérard Grisey.[18]

The "panoply of methods and techniques" used are secondary, being only "the means of achieving a sonic end".[3]

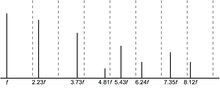

Spectral music focuses on the phenomenon and acoustics of sound rather than its potential semantic qualities. Pitch material and intervallic content are often derived from the harmonic series, including the use of microtones. Spectrographic analysis of acoustic sources is used as inspiration for orchestration. The reconstruction of electroacoustic source materials by acoustic instruments is another common approach to spectral orchestration. In "additive instrumental synthesis," instruments are assigned to play discrete components of a sound, such as an individual partial. Amplitude modulation, frequency modulation, difference tones, harmonic fusion, residue pitch, Shepard-tone phenomena, and other psychoacoustic concepts are applied to music materials.[19] Formal concepts important in spectral music include process and the stretching of time. Though development is "significantly different from those of minimalist music" in that all musical parameters may be affected, it similarly draws attention to very subtle aspects of the music. These processes most often achieve a smooth transition through interpolation.[20] Any or all of these techniques may be operating in a particular work, though this list is not exhaustive.

The Romanian spectral tradition focuses more on the study of how sound itself behaves in a "live" environment. Sound work is not restricted to harmonic spectra but includes transitory aspects of timbre and non-harmonic musical components (e.g., rhythm, tempo, dynamics). Furthermore, sound is treated phenomenologically as a dynamic presence to be encountered in listening (rather than as an object of scientific study). This approach results in a transformational musical language in which continuous change of the material displaces the central role accorded to structure in spectralism of the "French school".[21]

Composers

France

Spectral music was initially associated with composers of the French Ensemble l'Itinéraire, including Dufourt, Gérard Grisey, Tristan Murail, and Michael Levinas. For these composers, musical sound (or natural sound) is taken as a model for composition, leading to an interest in the exploration of the interior of sounds.[22] Giacinto Scelsi was an important influence on Grisey, Murail and Levinas; his approach with exploring a single sound in his works and a "smooth" conception of time (such as in his Quattro pezzi su una nota sola) greatly influenced these composers to include new instrumental techniques and variations of timbre in their works.[23]

Germany & Romania

Other spectral music composers include those from the German Feedback group, principally Johannes Fritsch, Mesias Maiguashca, Peter Eötvös, Claude Vivier, and Clarence Barlow. Features of spectralism are also seen independently in the contemporary work of Romanian composers Ştefan Niculescu, Horațiu Rădulescu, and Iancu Dumitrescu.[24]

United States

Independent of spectral music developments in Europe, American composer James Tenney's output included more than fifty significant works that feature spectralist traits.[25] His influences came from encounters with a scientific culture which pervaded during the postwar era, and a "quasi-empiricist musical aesthetic" from John Cage.[26] His works, although having similarities with European spectral music, are distinctive in some ways, for example in his interest in "post-Cageian indeterminacy".[26]

Post-spectralism

The spectralist movement inspired more recent composers such as Julian Anderson, Ana-Maria Avram, Joshua Fineberg, Georg Friedrich Haas, Jonathan Harvey, Fabien Lévy, Magnus Lindberg, and Kaija Saariaho.

Some of the "post-spectralist" French composers include Eric Tanguy, Philippe Hurel, François Paris, Philippe Leroux, and Thierry Blondeau.[27]

In the United States, composers such as Alvin Lucier, La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Maryanne Amacher, Phill Niblock, and Glenn Branca relate some of the influences of spectral music into their own work. Tenney's work has also influenced a number of composers such as Larry Polansky and John Luther Adams.[28]

In the USA, jazz saxophonist and composer Steve Lehman, and in Europe, French composer Frédéric_Maurin, have both introduced spectral techniques into the domain of jazz.[29]

Notable works

Characteristic spectral pieces include:

- Gérard Grisey: Les espaces acoustiques (Périodes and Partiels)

- Tristan Murail: Gondwana

Other pieces that utilise spectral ideas or techniques include:

- Gérard Grisey: Vortex Temporum

- Tristan Murail: Mémoire-Érosion[30]

- Michael Levinas: Appels[30]

- Karlheinz Stockhausen: Stimmung[30]

- James Tenney: Clang[26]

- James Tenney: Quintext[26]

Post-spectral pieces include:

- Georg Friedrich Haas: In Vain[31]

- John Chowning: Stria (1977)[32]

- Jonathan Harvey: Mortuos Plango, Vivos Voco (1980)

Stria and Mortuos Plango, Vivos Voco are examples of electronic music that embrace spectral techniques.[33]

See also

- Computer music

- Computer-assisted composition

- Electronic music

- IRCAM

- Spectrum analyzer

References

- Mabury 2006, 24.

- Moscovich 1997, .

- Fineberg 2000a, 2

- Anderson 2000, 7.

- Reigle 2008, .

- Rose 1996, 6; Moscovich 1997, 21–22; Anderson 2000, 8–14}}

- Anderson 2000, 8–13.

- Anderson 2000, 12, 20.

- Anderson 2000, 14.

- "... the question of timbre, though it is rigorously tackled by Schönberg (in his theory of the "melody of timbres") and above all by Webern, nevertheless has pre-serial origins, especially in Debussy—in this regard a "founding father" of the same rank as Schönberg. [...] Later, it also provided the grounds for the break with Boulez's "structural" orientations and the contestation of the legacy of serialism which was carried out by the French group L'Itinéraire (Gérard Grisey, Michaël Levinas, Tristan Murail ...)" (Badiou 2009, 82).

- Rose 1996, 7, 16.

- Anderson 2000, 15–17.

- Anderson 2000, 18.

- Halbreich 1992, 13–14.

- Anderson 2000, 21.

- Anderson 2000.

- Halbreich 1992, 50; Teodorescu-Ciocanea 2004, 144

- Grisey and Fineberg 2000, 3.

- Wannamaker 2008, 91–92.

- Fineberg 2000a, 107.

- Reigle 2008, 16.

- Murail 2005, 182–83

- Murail 2005, 183–84.

- Anderson 2001.

- Wannamaker 2008, 91

- Wannamaker 2008, 123

- Pugin 2001, 38–44.

- Wannamaker 2008, 123–24.

- Anon. 2009; Court and Florin 2015,

- Murail 2005, 181–85

- Fineberg 2000a, 128.

- McClellan n.d.

- Joos 2002; Sykes 2003.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Julian. 2000. "A Provisional History of Spectral Music". Contemporary Music Review 19, no. 2 ("Spectral Music: History and Techniques"): 7–22.

- Anderson, Julian. 2001. "Spectral Music". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- Anon. 2009. "Doctoral Student Continues Legacy of Professor's Spectral Music". Research: Breakthroughs in Knowledge and Ideas at Columbia website (Accessed 7 May 2012).

- Arrell, Chris. 2002. "Pushing the Envelope: Art and Science in the Music of Gérard Grisey". Doctoral Dissertation, Cornell University.

- Arrell, Chris. 2008. "The Music of Sound: An Analysis of Gérard Grisey's Partiels". In Spectral World Musics: Proceedings of the Istanbul Spectral Music Conference, edited by Robert Reigle and Paul Whitehead. Istanbul: Pan Yayincilik. ISBN 9944-396-27-3.

- Badiou, Alain. 2009. Logics of Worlds: The Sequel to Being and Event, translated by Alberto Toscano. London, New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-9470-2.

- Beldean, Laurentiu. "Philosophy, Liter[a]ture, and Tonal Music as Ingredients of Spectral Music". Transilvania University of Brasov. Series VII.

- Brow, Jefferey Arlo. 2018. "The Death and Life of Spectral Music". Van Magzine. 08, 23.

- Busoni, Ferruccio. 1907. "Entwurf einer neuen Ästhetik der Tonkunst". In Der mächtige Zauberer & Die Brautwahl: zwei Theaterdichtungen fur Musik; Entwurf einer neuen Aesthetik der Tonkunst, by Ferruccio Busoni, Arthur, comte de Gobineau, and E. T. A. Hoffmann. Triest: C. Schmidt. English edition as Sketch of a New Esthetic of Music, translated from the German by Th. Baker. New York: G. Schirmer, 1911.

- Cohen-Lévinas, Danielle. 1996. Création musicale et analyse aujourd'hui. Paris: Eska, 1996. ISBN 2-86911-510-5

- Cornicello, Anthony. 2000. "Timbral Organization in Tristan Murail's Désintégrations". Ph.D. Dissertation, Brandeis University.

- Court, Jean-Michel, and Ludovic Florin (eds.). 2015. Rencontres du jazz et de la musique contemporaine. Toulouse: Presses Universitaires du Midi. ISBN 978-2-8107-0374-6.

- Cowell, Henry. 1930. New Musical Resources. New York & London: A. A. Knopf. Reprinted, with notes and an accompanying essay by David Nicholls. Cambridge [England] & New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-521-49651-9 (cloth) ISBN 0-521-49974-7 (pbk.)

- Dufourt, Hugues. 1981. "Musique spectrale: pour une pratique des formes de l'énergie". Bicéphale, no.3:85–89.

- Dufourt, Hugues. 1991. Musique, pouvoir, écriture. Collection Musique/Passé/Présent. Paris: Christian Bourgois. ISBN 2-267-01023-2

- Fineberg, Joshua (ed.). 2000a. Spectral Music: History and Techniques. Amsterdam: Overseas Publishers Association, published by license under the Harwood Academic Publishers imprint, ©2000. ISBN 90-5755-131-4. Constituting Contemporary Music Review 19, no. 2.

- Fineberg, Joshua (ed.). 2000b. Spectral Music: Aesthetics and Music. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Overseas Publishers Association. ISBN 90-5755-132-2. Constituting Contemporary Music Review 19, no. 3.

- Fineberg, Joshua. 2006. Classical Music, Why Bother?: Hearing the World of Contemporary Culture Through a Composer's Ears. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-97174-8, ISBN 978-0-415-97174-4. [Contains much of the same text as Fineberg 2000a and 2000b.

- Grisey, Gérard. 1987. "Tempus ex machina: A Composer's Reflections on Musical Time." Contemporary Music Review 2, no. 1: 238–75.

- Grisey, Gérard and Fineberg, Joshua. 2000. "Did you say Spectral?". Contemporary Music Review 19, no. 3:1–3.

- Halbreich, Harry. 1992. Roumanie, terre du neuvième ciel. Bucharest: Axis Mundi.

- Harvey, Jonathan. 2001. "Spectralism". Contemporary Music Review 19, no. 3:11–14.

- Helmholtz, Hermann von. 1863. Die Lehre von den Tonempfindungen als physiologische Grundlage für die Theorie der Musik. Braunschweig: Friedrich Vieweg und Sohn. Second edition 1865; third edition 1870; fourth revised edition 1877; fifth edition 1896; sixth edition, edited by Richard Wachsmuth, Braunschweig: A. Vieweg & Sohn, 1913 (Facsimile reprints, Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1968; Frankfurt am Main: Minerva, 1981; Hildesheim & New York: G. Olms, 1983, 2000 ISBN 3-487-01974-4; Hildesheim: Olms-Weidmann, 2003 ISBN 3-487-11751-7; Saarbrücken: Müller, 2007 ISBN 3-8364-0606-3).

- Translated from the third edition by Alexander John Ellis, as On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music. London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1875; second English edition, revised and corrected, conformable to the 4th German edition of 1877 (London and New York: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1885); third English edition 1895; fourth English edition 1912; reprint of the 1912 edition, with a new introduction by Henry Margenau, New York: Dover Books, 1954 ISBN 0-486-60753-4; reprint of the 1912 edition, Whitefish, Montana: Kellinger Publishing, 2005, ISBN 1-4191-7893-8

- Humbertclaude Éric 1999. La Transcription dans Boulez et Murail: de l’oreille à l’éveil'. Paris: Harmattan. ISBN 2-7384-8042-X.

- Joos, Maxime. 2002. "'La cloche et la vague': Introduction à la musique spectrale—Tristan Murail et Jonathan Harvey". Musica falsa: Musique, art, philosophie, no. 16 (Fall): 30–31.

- Lévy, Fabien. 2004. "Le tournant des années 70: de la perception induite par la structure aux processus déduits de la perception". In Le temps de l'écoute: Gérard Grisey ou la beauté des ombres sonores, edited by Danièle Cohen-Levinas, 103–33. Paris: L'Harmattan/L'itinéraire. [Contains many typographical errors; corrected version online at: https://web.archive.org/web/20120907115503/http://www.fabienlevy.net/Documents/pdf/tournant70.pdf.]

- Mabury, Brett. 2006. "An Investigation into the Spectral Music Idiom and Its Association with Visual Imagery, Particularly That of Film and Video." MA thesis. Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts.

- McClellan, James. n.d. "James McClellan – Professor".

- Moscovich, Viviana. 1997. "French Spectral Music: An Introduction". Tempo new series, no. 200 (April): 21–27.

- Murail, Tristan (2005-04-01). "Scelsi and L'Itinéraire: The Exploration of Sound". Contemporary Music Review 24, nos. 2–3: 181–185. doi:10.1080/07494460500154830. ISSN 0749-4467.

- Pugin, Tristan. 2001. "Through the Spectrum: The New Intimacy in French Music (II)". Tempo (217): 38–47. ISSN 0040-2982.

- Reigle, Robert. 2008. "Spectral Musics Old and New". In Spectral World Musics: Proceedings of the Istanbul Spectral Music Conference, edited by Robert Reigle and Paul Whitehead, . Istanbul: Pan Yayincilik. ISBN 9944-396-27-3.

- Rose, François. 1996. "Introduction to the Pitch Organization of French Spectral Music." Perspectives of New Music 34, no. 2 (Summer): 6–39.

- Surianu, Horia. 2001. "Romanian Spectral Music or Another Expression Freed", translated by Joshua Fineberg. Contemporary Music Review 19, no. 3: 23–32.

- Sykes, Claire. 2003. "Spiritual Spectralism: The Music of Jonathan Harvey". Musicworks: Explorations in Sound, no. 87 (Fall): 30–37.

- Teodorescu-Ciocanea, Livia. 2004. Timbrul Muzical, Strategii de compoziţie. Bucharest: Editura Muzicală. ISBN 973-42-0344-4.

- Wannamaker, Robert A. 2008. "The Spectral Music of James Tenney". Contemporary Music Review 27, no. 1:91–130. doi:10.1080/07494460701671558

- Wilson, Andy [Editor]. 2013. "Cosmic Orgasm: The Music of Iancu Dumitrescu". Unkant Publishing. ISBN 095-68-1765-3.

External links

- Classical Nerd. 2017. "Great Composers: Horațiu Rădulescu." YouTube.

- Gann, Kyle. 2004. "Call It Spectral." The Village Voice (April 27).

- Hamilton, Andy. 2003. "The Primer: Spectral Composition." The Wire (November).

- Horatio Radulescu – Homepage

- IRCAM page on Gérard Grisey (IRCAM composer biographies in French)

- IRCAM page on Horatio Radulescu

- IRCAM page on Hugues Dufourt

- IRCAM page on Joshua Fineberg

- IRCAM page on Philippe Hurel

- IRCAM page on Philippe Leroux

- IRCAM page on Marco Stroppa

- Service, Tom. 2013. "A guide to Gérard Grisey's music." The Guardian (March 18).

- Service, Tom. 2012. "A guide to Kaija Saariaho's music." The Guardian (July 9).

- Spectral Music (University of York course description, 2013; bibliography under tab for Reading and Listening)

- Tristan Murail – Accueil/Homepage

- Gérard Grisey – Vortex Temporum (for six instruments) (1995) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rXaNFBzgDWI&t=12s

- GÉRARD GRISEY – "Les Espaces Acoustiques" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IXQ5c8GUsUM&t=126s