Special Order 191

Special Order 191 (series 1862), also known as the "Lost Dispatch" and the "Lost Order", was a general movement order issued by Confederate Army General Robert E. Lee on about September 9, 1862, during the Maryland Campaign of the American Civil War. A lost copy of this order was recovered on September 13 by Union Army troops in Frederick County, Maryland, and the subsequent military intelligence gained by the Union played an important role in the Battle of South Mountain and Battle of Antietam.

History

The order was drafted on or about September 9, 1862, during the Maryland Campaign. It gave details of the movements of the Army of Northern Virginia during the early days of its invasion of Maryland. Lee divided his army, which he planned to regroup later; according to the precise text Major General Stonewall Jackson was to move his command to Martinsburg while McLaws's command and Walker's command "endeavored to capture Harpers Ferry." Major General James Longstreet was to move his command northward to Boonsborough. Major General D. H. Hill's division was to act as rear guard on the march from Frederick.

Lee delineated the routes and roads to be taken and the timing for the investment of Harpers Ferry. Adjutant Robert H. Chilton penned copies of the letter and endorsed them in Lee's name. Staff officers distributed the copies to various Confederate generals. Jackson in turn copied the document for one of his subordinates, D. H. Hill, who was to exercise independent command as the rear guard. Hill said the only copy he received was the one from Jackson.[1]

About noon[2] on September 13, Corporal Barton W. Mitchell of the 27th Indiana Volunteers, part of the Union XII Corps, discovered an envelope with three cigars wrapped in a piece of paper lying in the grass at a campground that Hill had just vacated. Mitchell realized the significance of the document and turned it in to Sergeant John M. Bloss. They went to Captain Peter Kopp, who sent it to regimental commander Colonel Silas Colgrove, who carried it to the corps headquarters. There, an aide to Brigadier General Alpheus S. Williams recognized the signature of R. H. Chilton, the assistant adjutant general who had signed the order. Williams's aide, Colonel Samuel Pittman, recognized Chilton's signature because Pittman frequently paid drafts drawn under Chilton's signature before the war. Pittman worked for a Detroit bank during the period when Chilton was paymaster at a nearby army post.[3][4] Williams forwarded the dispatch to Major General George B. McClellan, the commander of the Army of the Potomac. McClellan was overcome with glee at learning planned Confederate troop movements and reportedly exclaimed, "Now I know what to do!" He confided to Brigadier General John Gibbon, "Here is a paper with which, if I cannot whip Bobby Lee, I will be willing to go home."[5]

McClellan stopped Lee's invasion at the subsequent Battle of Antietam, but many military historians believe he failed to fully exploit the strategic advantage of the intelligence because he was concerned about a possible trap (posited by Major General Henry W. Halleck) or gross overestimation of the strength of Lee's army.

The hill on the Best Farm where the lost order was discovered is located outside of Frederick, Maryland, and was a key Confederate artillery position in the 1864 Battle of Monocacy. A historical marker on the Monocacy National Battlefield commemorates the finding of Special Order 191 during the Maryland Campaign.

Corporal Mitchell, who found the orders, was subsequently wounded in the leg at Antietam and was discharged in 1864 due to the resulting chronic infection. He died in 1868 at the age of 52.

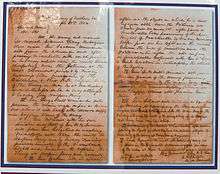

Special Orders, No. 191

Special Orders, No. 191

Hdqrs. Army of Northern Virginia

September 9, 1862

- The citizens of Fredericktown being unwilling while overrun by members of this army, to open their stores, to give them confidence, and to secure to officers and men purchasing supplies for benefit of this command, all officers and men of this army are strictly prohibited from visiting Fredericktown except on business, in which cases they will bear evidence of this in writing from division commanders. The provost-marshal in Fredericktown will see that his guard rigidly enforces this order.

- Major Taylor will proceed to Leesburg, Virginia, and arrange for transportation of the sick and those unable to walk to Winchester, securing the transportation of the country for this purpose. The route between this and Culpepper Court-House east of the mountains being unsafe, will no longer be traveled. Those on the way to this army already across the river will move up promptly; all others will proceed to Winchester collectively and under command of officers, at which point, being the general depot of this army, its movements will be known and instructions given by commanding officer regulating further movements.

- The army will resume its march tomorrow, taking the Hagerstown road. General Jackson's command will form the advance, and, after passing Middletown, with such portion as he may select, take the route toward Sharpsburg, cross the Potomac at the most convenient point, and by Friday morning take possession of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, capture such of them as may be at Martinsburg, and intercept such as may attempt to escape from Harpers Ferry.

- General Longstreet's command will pursue the same road as far as Boonsborough, where it will halt, with reserve, supply, and baggage trains of the army.

- General McLaws, with his own division and that of General R. H. Anderson, will follow General Longstreet. On reaching Middletown will take the route to Harpers Ferry, and by Friday morning possess himself of the Maryland Heights and endeavor to capture the enemy at Harpers Ferry and vicinity.

- General Walker, with his division, after accomplishing the object in which he is now engaged, will cross the Potomac at Cheek's Ford, ascend its right bank to Lovettsville, take possession of Loudoun Heights, if practicable, by Friday morning, Key's Ford on his left, and the road between the end of the mountain and the Potomac on his right. He will, as far as practicable, cooperate with General McLaws and Jackson, and intercept retreat of the enemy.

- General D. H. Hill's division will form the rear guard of the army, pursuing the road taken by the main body. The reserve artillery, ordnance, and supply trains, &c., will precede General Hill.

- General Stuart will detach a squadron of cavalry to accompany the commands of Generals Longstreet, Jackson, and McLaws, and, with the main body of the cavalry, will cover the route of the army, bringing up all stragglers that may have been left behind.

- The commands of Generals Jackson, McLaws, and Walker, after accomplishing the objects for which they have been detached, will join the main body of the army at Boonsborough or Hagerstown.

- Each regiment on the march will habitually carry its axes in the regimental ordnance—wagons, for use of the men at their encampments, to procure wood &c.

By command of General R. E. Lee

R.H. Chilton, Assistant Adjutant General[6]

In popular culture

In Harry Turtledove's Southern Victory Series alternate history novels, the point of divergence with recorded history is that the order is not discovered by Union troops, but is instead recovered by a trailing Confederate soldier, allowing the Confederate army to move faster and win the war. In What If? and What Ifs? of American History, the scenario "If the Lost Order Hadn't Been Lost" by James M. McPherson also has a similar conclusion to Turtledove with Robert E. Lee advancing up to Pennsylvania and winning the decisive victory in an early version of the Battle of Gettysburg.

Union troops not discovering the order is also the point of divergence for the alternate reality superhero comic book series Captain Confederacy.

Bernard Cornwell's novel The Bloody Ground, part of the Starbuck Chronicles, fictionalizes the events and lead-up of Antietam, in which the order is central to the drama in the lead-up to the battle and an explanation is offered for how it ended up discarded in the field.

References

- "Civil War Papers of Samuel E. Pittman, Lt. Col., 1861-1925." Am Mss Pittman. Chapin Library, Williams College.

- Harsh, Joseph L. Taken at the Flood: Robert E. Lee & Confederate Strategy in the Maryland Campaign of 1862. 1999, ISBN 0-87338-631-0.

- Jones, Wilbur D., Who Lost the Lost Order?.

- Leigh, Philip "Lee's Lost Dispatch and Other Civil War Controversies." (Yardley, Penna.: Westholme Publishing, 2015), ISBN 978-159416-226-8

- Sears, Stephen W., Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam, 1983 (1985 Popular Library edition), ISBN 0-89919-172-X.

- Seeds/McMoneagle, "Civil War Lost Order Mystery Solved", 2012 (Logistics News Network, LLC. on The Evidential Details Mystery Series Imprint) ISBN 978-0-9826928-6-8

Notes

- Sears pp. 100-101, 126

- "McClellan Reacts to the "Lost Order"September 13, 1862". Antietam on the Web. Retrieved 2013-01-24.

- Philip Leigh "Lee's Lost Dispatch and Other Civil War Controversies" (Yardley, Penna. Westholme Publishing, 2015), 138

- "Civil War Papers of Samuel E. Pittman, Lt. Col." Am Mss Pittman. Chapin Library, Williams College.

- Sears, p. 123-125

- Harsh pp. 154-164

External links

- "Catalog: Special Order No. 191 from General Robert E. Lee". U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.