Ultima (series)

Ultima is a series of open world fantasy role-playing video games from Origin Systems, Inc. Ultima was created by Richard Garriott. The series is one of the most significant in computer game history and is considered, alongside Wizardry and Might and Magic, to be one of the establishers of the CRPG genre.[1] Several games of the series are considered seminal entries in their genre, and each installment introduced new innovations which then were widely copied by other games. Electronic Arts owns the brand.

| Ultima | |

|---|---|

The most commonly used logo in the series | |

| Genre(s) | Role-playing video game |

| Developer(s) | Origin Systems Blue Sky Productions Looking Glass Studios Electronic Arts Bioware Mythic |

| Publisher(s) | Origin Systems Electronic Arts |

| Creator(s) | Richard Garriott |

| Platform(s) | Apple II, Atari 8-bit, VIC-20, C64, DOS, MSX, FM Towns, NEC PC-9801, Atari ST, Mac OS, Amiga, Atari 800, NES, Master System, C128, SNES, X68000, PlayStation, Windows |

| First release | Ultima I: The First Age of Darkness 1981 |

| Latest release | Ultima Forever: Quest for the Avatar 2013 |

The games take place for the most part in a world called Britannia; the constantly recurring hero is the Avatar, first named so in Ultima IV. They are primarily within the scope of fantasy fiction but contain science fiction elements as well.

Games

The main Ultima series consists of nine installments (the seventh title is further divided into two parts) grouped into three trilogies, or "Ages": The Age of Darkness (Ultima I-III), The Age of Enlightenment (Ultima IV-VI), and The Age of Armageddon (Ultima VII-IX). The last is also sometimes referred to as "The Guardian Saga" after its chief antagonist. The first trilogy is set in a fantasy world named Sosaria, but during the cataclysmic events of The Age of Darkness, it is sundered and three quarters of it vanish. What is left becomes known as Britannia, a realm ruled by the benevolent Lord British, and is where the later games mostly take place. The protagonist in all the games is a canonically male resident of Earth who is called upon by Lord British to protect Sosaria and, later, Britannia from a number of dangers. Originally, the player character was referred to as "the Stranger", but by the end of Ultima IV he becomes universally known as the Avatar.

Main series

The Age of Darkness: Ultima I–III

| 1979 | Akalabeth |

|---|---|

| 1980 | |

| 1981 | Ultima I |

| 1982 | Ultima II |

| 1983 | Ultima III |

| 1984 | |

| 1985 | Ultima IV |

| 1986 | |

| 1987 | |

| 1988 | Ultima V |

| 1989 | |

| 1990 | Ultima VI |

| 1991 | |

| 1992 | Ultima VII |

| 1993 | Ultima VII part Two |

| 1994 | Ultima VIII |

| 1995 | |

| 1996 | |

| 1997 | |

| 1998 | |

| 1999 | Ultima IX |

In Ultima I: The First Age of Darkness (1981),[2] the Stranger is first summoned to Sosaria to defeat the evil wizard Mondain who aims to enslave it. Since Mondain possesses the Gem of Immortality, which makes him invulnerable, the Stranger locates a time machine, travels back in time to kill Mondain before he creates the Gem, and shatters the incomplete artifact.

Ultima II: The Revenge of the Enchantress (1982) details Mondain's secret student and lover Minax's attempt to avenge him. When Minax launches an attack on the Stranger's homeworld of Earth, her actions cause doorways to open to various times and locations throughout Earth's history, and brings forth legions of monsters to all of them. The Stranger, after obtaining the Quicksword that alone can harm her, locates the evil sorceress at Castle Shadowguard at the origin of time and defeats her.

Ultima III: Exodus (1983) reveals that Mondain and Minax had an offspring, the eponymous Exodus, "neither human, nor machine", according to the later games (it is depicted as a computer at the conclusion of the game, and it appears to be a demonic, self-aware artificial intelligence). Some time after Minax's death, Exodus starts its own attack on Sosaria and the Stranger is summoned once again to destroy it. Exodus was the first installment of the series featuring a player party system, which was used in many later games.

The Age of Enlightenment: Ultima IV–VI

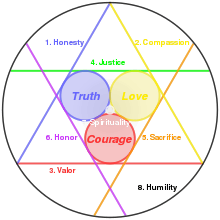

Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar (1985) marked a turning point in the series from the traditional "hero vs. villain" plots, instead introducing a complex alignment system based upon the Eight Virtues derived from the combinations of the Three Principles of Love, Truth and Courage. Although Britannia now prospers under Lord British's rule, he fears for his subjects' spiritual well-being and summons the Stranger again to become a spiritual leader of Britannian people by example. Throughout the game, the Stranger's actions determine how close he comes to this ideal. Upon achieving enlightenment in every Virtue, he can reach the Codex of Ultimate Wisdom and becomes the "Avatar", the embodiment of Britannia's virtues.

In Ultima V: Warriors of Destiny (1988), the Avatar returns to Britannia to find that after Lord British had been lost in the Underworld, Lord Blackthorn, who rules in his stead, was corrupted by the Shadowlords and enforces a radically twisted vision of the Virtues, deviating considerably from their original meaning. The Avatar and his companions proceed to rescue the true king, overthrow the tyrant, and restore the Virtues in their true form.

Ultima VI: The False Prophet (1990) details the invasion of Britannia by Gargoyles, which the Avatar and his companions have to repel. Over the course of the game, it is revealed that the Gargoyles have valid reasons to loathe the Avatar. Exploring the themes of racism and xenophobia, the game tasks the Avatar with understanding and reconciling two seemingly opposing cultures.

The Age of Armageddon: Ultima VII–IX

Ultima VII: The Black Gate (1992) sees the Avatar entangled in the plan of an ostensibly virtuous and benevolent organization named the Fellowship (inspired by Scientology)[3][4] to create a gateway for the evil entity known as the Guardian to enter Britannia. Though all of the main line of Ultima games are arranged into trilogies, Richard Garriott later revealed that Ultima VII was the first game where he did any sort of planning ahead for future games in the series. He elaborated that "the first three didn't have much to do with each other, they were 'Richard Garriott learns to program'; IV through VI were a backwards-designed trilogy, in the sense that I tied them together as I wrote them; but VII-IX, the story of the Guardian, were a preplanned trilogy, and we had a definite idea of where we wanted to go."[5] An expansion pack was released named Forge of Virtue that added a newly arisen volcanic island to the map that the Avatar was invited to investigate. The tie-in storyline was limited to this island, where a piece of Exodus (his data storage unit) had resurfaced. To leave the island again, the Avatar had to destroy this remnant of Exodus. In the process of doing so, he also created The Black Sword, an immensely powerful weapon possessed by a demon.

Ultima VII Part Two: Serpent Isle (1993) was released as the second part of Ultima VII because it used the same game engine as Ultima VII. According to interviews, Richard Garriott felt it therefore did not warrant a new number. Production was rushed due to deadlines set to the developers, and the storyline was cut short; remains of the original, longer storyline can be found in the database. Following the Fellowship's defeat, its founder Batlin flees to the Serpent Isle, pursued by the Avatar and companions. Serpent Isle is revealed as another fragment of former Sosaria, and its history which is revealed throughout the game provides many explanations and ties up many loose ends left over from the Age of Darkness era. Magical storms herald the unraveling of the dying world's very fabric, and the game's mood is notably melancholic, including the voluntary sacrificial death of a long-standing companion of the Avatar, Dupre. By the end of the game, the Avatar is abducted by the Guardian and thrown into another world, which becomes the setting for the next game in the series. The Silver Seed was an expansion pack for Ultima VII Part 2 where the Avatar travels back in time to plant a silver seed, thus balancing the forces that hold the Serpent Isle together. Like Forge of Virtue, the expansion contained an isolated sub-quest that was irrelevant to the main game's storyline, but provided the Avatar with a plethora of useful and powerful artifacts.

In Ultima VIII: Pagan (1994), the Avatar finds himself exiled by the Guardian to a world called "Pagan". The Britannic Principles and Virtues are unknown here. Pagan is ruled by the Elemental Titans, god-like servants of the Guardian. The Avatar defeats them with their own magic, ascending to demi-godhood himself, and finally returns to Britannia. A planned expansion pack, The Lost Vale, was canceled after Ultima VIII failed to meet sales expectations.

Ultima IX: Ascension (1999), the final installment of the series, sees Britannia conquered and its Virtues corrupted by the Guardian. The Avatar has to cleanse and restore them. The Guardian is revealed to be the evil part of the Avatar himself, expelled from him when he became the Avatar. To stop it, he has to merge with it, destroying himself as a separate entity. The unreleased version of the plot featured a more apocalyptic ending, with the Guardian and Lord British killed, Britannia destroyed, and the Avatar ascending to a higher plane of existence.

Collections

- Ultima Trilogy (1989) – an early compilation of the first three Ultima games released for the Apple II, Commodore 64 and DOS by Origin Systems.

- Ultima: The Second Trilogy (1992) – a later trilogy of the second three Ultima games released by Origin Systems for Commodore 64 and DOS.

- Ultima I–VI Series (1992) – a compilation of the first six Ultima games and published for DOS by Software Toolworks. Includes reprints of the instruction manuals and original maps.

- Ultima Collection (1998) – a CD-ROM collection of the first eight Ultima computer games published for DOS and Microsoft Windows 95/98, including their expansion packs. Includes a complete atlas of each game's map, a PC port of Akalabeth, and a sneak preview of Ultima IX.

Spin-offs and other games

Akalabeth: World of Doom was released in 1979, and is sometimes considered a precursor to the Ultima series.

Sierra On-Line also produced Ultima: Escape from Mt. Drash in 1983. The maze game has nothing in common with the others,[6][7] but is highly sought after by collectors due to extreme rarity.

The Worlds of Ultima series is a spin-off of Ultima VI using the same game engine, following the Avatar's adventures after the game's conclusion:

- In Worlds of Ultima: The Savage Empire (1990), a failed experiment transports the Avatar to the Valley of Eodon, a jungle world populated by thirteen primitive tribes whom he must unite against a common enemy, the insectoid Myrmidex.

- Ultima: Worlds of Adventure 2: Martian Dreams (1991) takes place after The Savage Empire and sees the Avatar travel back in time to the Victorian era and eventually land on Mars to rescue humans stranded on it by accident and to restore the native Martian civilization.

- The third game, Ultima: Worlds of Adventure 3: Arthurian Legends, was planned to be set in the times of King Arthur but was canceled in 1993.

The second spin-off series, Ultima Underworld, consisted of two games:

- Set after Ultima VI, Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss (1992) sees the Avatar descending into the Great Stygian Abyss to rescue a Britannian baron's kidnapped daughter and prevent the summoning of a powerful demon.

- Ultima Underworld II: Labyrinth of Worlds (1993) is set between the two parts of Ultima VII and starts with the Guardian trapping Lord British, the Avatar and his companions within an impenetrable barrier in their castle. To free them, the Avatar has to travel through several parallel universes looking for a way to undo the spell.

A group of volunteer programmers created Ultima V: Lazarus in 2006, a remake of Ultima V using the Dungeon Siege engine.

And another group of volunteer programmers created Ultima VI Project in 2010, a remake of Ultima VI using also the Dungeon Siege engine.

Console games

Console versions of Ultima have allowed further exposure to the series, especially in Japan where the games have been bestsellers and were accompanied by several tie-in products including Ultima cartoons and manga.[8] In most cases, gameplay and graphics have been changed significantly.

Console ports of computer games

- Ultima III: Exodus (NES)

- Ultima: Quest of the Avatar (NES) - Remake: includes plot and gameplay changes.

- Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar (Sega Master System) — A faithful port of the original. Only released in Europe and South America.

- Ultima V: Warriors of Destiny (NES)

- Ultima VI: The False Prophet (SNES) — Gameplay adapted for the game pad.

- Ultima: The Black Gate (SNES) — Action-adventure remake.

- Ultima: The Savage Empire (SNES) — A graphical update using the Black Gate engine for the SNES. Japan only, canceled in the US.

- Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss (PlayStation) — Uses 3D models rather than the 2D sprites of the original. Released only in Japan.

Original console games

Ultima Online MMORPG

Ultima Online (1997), a MMORPG spin-off of the main series, has become an unexpected hit, making it one of the earliest and longest-running successful MMORPGs of all time. Its lore retconned the ending of Ultima I, stating that when the Stranger shattered the Gem of Immortality, he discovered that it was tied to the world itself, therefore its shards each contained a miniature version of Britannia. The player characters in Ultima Online exist on these "shards". Eight expansion packs for UO have been released (The Second Age, Renaissance, Third Dawn, Lord Blackthorn's Revenge, Age of Shadows, Samurai Empire, Mondain's Legacy and Stygian Abyss) . The aging UO graphic engine was renewed in 2007 with the official Kingdom Reborn client. Ultima Online 2, later renamed to Ultima Worlds Online: Origin and canceled in 2001, would have introduced steampunk elements to the game world, following Lord British's unsuccessful attempt to merge past, present, and future shards together.

UO spawned two sequel efforts that were canceled before release: Ultima Worlds Online: Origin (canceled in 2001, though the game's storyline was published in the Technocrat War trilogy) and Ultima X: Odyssey (canceled in 2004). Ultima X: Odyssey (2004) would have continued the story of Ultima IX. Now merged with the Guardian, the Avatar creates a world of Alucinor inside his mind, where the players were supposed to pursue the Eight Virtues in order to strengthen him and weaken the Guardian. Ultima X was developed without participation of the original creator Richard Garriott and he no longer owns the rights to the series. However, he still owns the rights to several of the game characters so it is impossible for either him or Electronic Arts to produce a new Ultima title without getting permission from each other.

Lord of Ultima

Lord of Ultima was a free-to-play browser-based MMORTS released in 2010 by EA Phenomic. It was the first release in the Ultima series since Ultima Online, and also the first title to have no involvement from series creator Garriott or founding company Origin. It has been criticized for having slow-paced gameplay and very weak connections to the Ultima franchise lore. EA announced on February 12, 2014 that Lord of Ultima would be shut down and taken offline as of May 12, 2014.

Ultima Forever: Quest for the Avatar

Announced in summer 2012, Ultima Forever was a free-to-play online action role-playing game. In contrast to Lord of Ultima, Ultima Forever returns to the lore of the original game series. As of August 29, 2014. Ultima Forever's servers were shut down.

Other media

Several novels were released under the Ultima name, including:

- The Ultima Saga by Lynn Abbey (Warner Books)

- Ultima: The Technocrat War by Austen Andrews (Pocket Books)

- Machinations (2001)

- Masquerade (2002)

- Maelstrom (2002)

In Japan, an Ultima soundtrack CD, two kinds of wrist watches, a tape dispenser, a pencil holder, a board game, a jacket, and a beach towel were released. There was also an Ultima anime cartoon.[12]

Three manga comics were released in Japan:

- Ultima: EXODUS No Kyoufu (The Terror of EXODUS)

- Ultima: Quest of the Avatar

- Ultima: Magincia no Metsubou (The Fall of Magincia)

- Ultima: The Maze of Schwarzschild

Packaging

Ultima game boxes often contained so-called "feelies"; e.g. from Ultima II on, every game in the main series came with a cloth map of the game world. Starting with Ultima IV, small trinkets like pendants, coins and magic stones were found in the boxes. Made of metal or glass, they usually represented an important object also found within the game itself.

Not liking how games were sold in zip lock bags with a few pages printed out for instructions, Richard Garriott insisted Ultima II be sold in a box, with a cloth map, and a manual.[13][14] Sierra was the only company at that time willing to agree to this, and thus he signed with them.

Copy protection measures

In the Atari 8bit version of Ultima IV one of the floppy disks had an unformatted track. In its absence the player would lose on every fight, which would not be obvious as a copy protection effect right away as one could assume that this was just due to either lack of experience or proper equipment. The protection mechanism was subtle enough to be overlooked by the German distributor which originally delivered Atari 8bit packages with floppies that were formatted regularly, and thus these paid copies acted like unlicensed copies, causing players to lose every battle.[15]

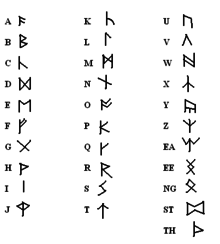

In Ultima V, there were one or two instances where ostensibly insignificant information found in the accompanying booklet were asked by person(s) encountered in the game. The game also used runic script in some places and a special language for spell names, for both of which the necessary translation tables / explanations were provided in the booklet. These can be seen as subtle copy-protection measures, well fitted for the context of history and fantasy so that a casual player didn't take them for copy protection.[16]

Ultima VI introduced a more systematic use of copy protection in the form of in-game questions, preventing the player from progressing any further if the questions were answered incorrectly.[17] In Ultima VII, this practice was continued, although in both games the player had an unlimited number of tries to answer the questions correctly. Answers could be obtained by consulting the manual or cloth map, although the manual released with the Ultima Collection contained all copy protection answers for every game.[18]

In Ultima VII Part 2: Serpent Isle, the copy protection was changed slightly. Players were asked questions at two points in the game, and if they could not answer after two attempts, all NPCs said nothing but altered versions of famous quotes, such as "My kingdom for a hammer!", "Honor thy father and thy hoe, babycakes" and "Oh my, twig, I don't think we're in Britannia anymore". Everything would also be labeled "Oink!", preventing the game from being played. From Ultima VIII onward, copy protection questions were discontinued.[19]

Common elements

Setting

Originally, the world of Ultima was made up of four continents. These were Lord British's Realm, ruled by Lord British and the Lost King; The Lands of Danger and Despair, ruled by Lord Shamino and the King of the White Dragon; The Lands of the Dark Unknown, ruled by Lord Olympus and the King of the Black Dragon; and The Lands of the Feudal Lords, ruled by the lords of Castle Rondorin and Castle Barataria.

After the defeat of Mondain and the shattering of his Gem of Immortality in Ultima I, there was a cataclysm that changed the structure of the world. Three of the four continents seemingly disappeared, leaving only Lord British's realm in the world. This remaining continent was referred from then on as "Sosaria". The Lands of Danger and Despair were later rediscovered as the Serpent Isle, which had been moved to a different dimension or plane, so it seems likely that the other two continents still exist. Ultima II shows Castle Barataria on Planet X, suggesting that the Lands of the Feudal Lords became this planet; Ultima Online: Samurai Empire posits that the Lands of the Feudal Lords was transformed into the Tokuno Islands by the cataclysm.

After the defeat of Exodus in Ultima III, Sosaria became Britannia in order to honor its ruler, Lord British. Serpent Isle remained connected with Britannia via a gate in the polar region. The Fellowship leader, Batlin, fled here after the Black Gate was destroyed in Ultima VII, preventing the Guardian's first invasion. Ninety percent of the island's population was destroyed by evil Banes released by Batlin in a foolish attempt to capture them for his own use in Ultima VII Part 2.

Virtues

In Ultima, the player takes the role of the Avatar, who embodies eight virtues. First introduced in Ultima IV, the Three Principles and the Eight Virtues marked a reinvention of the game focus from a traditional role-playing model into an ethically framed one.[20] Each virtue is associated with a party member, one of Britannia's cities, and one of the eight other planets in Britannia's solar system. Each virtue also has a mantra and each principle a word of power that the player must learn. The Eight Virtues explored in Ultima are Honesty, Compassion, Valor, Justice, Sacrifice, Honor, Spirituality, and Humility. These Eight Virtues are based on the Three Principles of Truth, Love, and Courage. The Principles are derived from the One True Axiom, the combination of all Truth, all Love, and all Courage, which is Infinity.[20][21]

The virtues were first introduced in Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar (1985), where the goal of the game is to practice them and become a moral exemplar. Virtues and their variations are present in all later installments. Richard Garriott's motives in designing the virtue system were to build on the fact that games were provoking thought in the player, even unintentionally. As a designer, he "wasn't interested in teaching any specific lesson; instead, his next game would be about making people think about the consequences of their actions."[22] The original virtue system in Ultima was partially inspired by the 16 ways of purification (sanskara) and character traits (samskara) which lead to Avatarhood in Hinduism.[20][23] He also drew on his interpretation of characters from The Wizard of Oz, with the Scarecrow representing truth, the Tin Woodsman representing love, and the Cowardly Lion representing courage.[24]

The Virtues have become a frequent theme in the Ultima games following Ultima IV, with many different variants used throughout the series. Ultima V: Warriors of Destiny saw Lord Blackthorn turn the virtue system into a rigid and draconian set of laws.[25] The rigid system of Blackthorn unintentionally causes the Virtues to actually achieve their polar opposites, in part due to the influence of the Shadowlords. This shows that the Virtues always come from one's own self, and that codifying ethics into law does not automatically make evil people good.[20] Ultima VI: The False Prophet confronted the Avatar with the fact that, from another point of view, the Avatar's quests for Virtue may not appear virtuous at all, presenting an alternative set of virtues.[26] In Ultima VII, an order known as the Fellowship displaced the Virtues with its own seemingly benevolent belief system, casting Britannia into disarray; and in Ultima IX, the Virtues had been inverted into their opposite anti-virtues.

Ultima's virtue system was considered a new frontier in game design,[27] and has become "an industry standard, especially within role-playing games."[28] The original system from Ultima IV has influenced moral systems in games such as Black & White, Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic and the Fable series.[28][29] However, Ultima can only be won by being virtuous, while other games typically offer a choice to be vicious.[29] Mark Hayse specifically praises Ultima's virtue system for its subtlety. The game emphasizes the importance of virtue, but leaves the practice ambiguous with no explicit point values and limited guidance. This makes the virtue system more of a "philosophical journey" than an ordinary game puzzle.[28]

Characters

Artificial scripts and language

The Ultima series of computer games employed several different artificial scripts. The people of Britannia, the fantasy world where the games are set, speak English, and most of the day-to-day things are written in Latin alphabet. However, there still are other scripts, which are used by tradition.

Britannian runes are the most commonly seen script. In many of the games of the series, most signs are written in runic. The runes are based on Germanic runes, but closer to Dwarven runes in Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, which creator Richard Garriott has stated he has read. They gained steadier use since Ultima V, which was the first game in the series to use a runic font for in-game signs. Runes in earlier games were mostly found in hard copy materials, such as maps and the decorative covers of booklets. Runes appear less in Ultima VII and in later games.

Gargish is the language of the gargoyles of Britannia and the language used in spellcasting within the game. Unlike the runic script, which is usually used simply as a visual cipher for English, the Gargish script encodes a genuine constructed language, based on (but expanding greatly upon) the magical words of power that first saw use in Ultima V, as well as the mantras for each of the Shrines of Virtue, which had remained consistent since Ultima IV. The lexicon mostly comprises deformed or truncated Latinate stems (flam "fire" ← Latin flamma; lap "stone" ← Latin lapis; leg "to read" ← Latin legō), but other origins are also apparent (uis "wisdom" ← English wise; kas "helmet" ← French casque). But the grammar is de novo and bears little resemblance to Latin, being largely analytic in structure instead. Gargish uses suffixes to denote grammatical tense and aspect, and also in some forms of derivation. The Gargish alphabet is featured in Ultima VI, though it is seen only in specific game contexts. Ultima VII and onward does not feature anything written in the alphabet, with the sole exception of some books to be found in the gargoyle colony in the underwater city of Ambrosia in Ultima IX. The Gargish language and alphabet were designed by Herman Miller.

The Ophidian alphabet, featured in Ultima VII Part Two: Serpent Isle, was used by the Ophidian civilization that inhabited the Serpent Isle. It is based on various snake forms. Ophidian lettering was quite difficult to read, so the game included a Translation spell that made the letters look like Latin letters.

Reception

In 1996, Next Generation ranked the Ultima series as collectively the 55th top game of all time, commenting that, "While the graphics and playing style change with the technological leaps of the day, [it] has been the most consistent source of roleplaying excitement in history."[30] In 1999, Next Generation listed the Ultima series as number 18 on their "Top 50 Games of All Time", commenting that, "Most PC RPGs are about hacking and slashing through anything that moves, usually while crawling through a dungeon. The Ultima series, however, has always been firmly grounded in a world where a character's virtues are as important as their armor class in determining success."[31] In 2000, Britannia was included in GameSpot's list of the ten best game worlds, called "the oldest and one of the most historically rich gameworlds."[32]

By 1990, total sales of Pony Canyon's Japanese versions of the Ultima series had reached nearly 100,000 copies on computers, and over 300,000 units on the Famicom.[33]

Impact and legacy

Many innovations of the early Ultimas – in particular Ultima III: Exodus (1983) – eventually became standard among later RPGs, such as the use of tiled graphics and party-based combat, its mix of fantasy and science-fiction elements, and the introduction of time travel as a plot device.[34] In turn, some of these elements were inspired by Wizardry, specifically the party-based combat.[35] Exodus was also revolutionary in its use of a written narrative to convey a larger story than the typically minimal plots that were common at the time. Most video games – including Garriott's own Ultima I and II and Akalabeth – tended to focus primarily on things like combat without venturing much further.[36] In addition, Garriott would introduce in Ultima IV a theme that would persist throughout later Ultimas – a system of chivalry and code of conduct in which the player, or "Avatar", is tested periodically (in both obvious and unseen ways) and judged according to his or her actions. This system of morals and ethics was unique, in that in other video games players could for the most part act and do as they wished without having to consider the consequences of their actions.[36]

Ultima III would go on to be released for many other platforms and influence the development of such RPGs as Excalibur and Dragon Quest;[37] and many consider the game to be the first modern CRPG.[34]

On June 30, 2020, Garriott said he was turned down by EA for any attempts to revive or remaster the Ultima series.[38]

Shroud of the Avatar: Forsaken Virtues

Richard Garriott's new company Portalarium developed an RPG/MMORPG that Garriott has described as a clear spiritual successor of the Ultima series.[39] On March 8, 2013, Portalarium launched a Kickstarter campaign[40] for Shroud of the Avatar: Forsaken Virtues.[41] Forsaken Virtues is the first of five full-length episodic installments in Shroud of the Avatar and was designed as a "Selective Multiplayer Game". This allowed the player to determine his or her level of multiplayer involvement that ranges from MMO to single player offline. Despite original plans to launch in Summer 2017,[42] with Episodes 2 through 5 estimated for subsequent yearly releases,[43] the first episode would ultimately be released on March 27, 2018 to mixed reception. Further episodes have not yet been released.

References

- Barton, Matt (2007-02-23). "The History of Computer Role-Playing Games Part 2: The Golden Age (1985-1993)". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2018-10-25.

- "List of Top Sellers", Computer Gaming World, 2 (5), p. 2, September–October 1982

- Prima's official strategy guide – Ultima Ascension, page 271

- "Features – The History of Computer Role-Playing Games Part III: The Platinum and Modern Ages (1994–2004)". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2012-09-02.

- "NG Alphas: Ultima IX: Ascension". Next Generation. No. 22. Imagine Media. October 1996. pp. 154–5.

- Bolingbroke, Chester (2014-08-24). "Game 160: Ultima: Escape from Mount Drash (1983)". The Computer Role-playing Game Addict. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- Maher, Jimmy (2013-05-16). "The Legend of Escape from Mt. Drash". The Digital Antiquarian. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- "75 Power Players". Next Generation. Imagine Media (11): 68–69. November 1995.

- "Gamespot ''The Ultima Legacy''". Gamespot.com. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- "Forge of Virtue". Lynnabbey.com. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- "Temper of Wisdom". Lynnabbey.com. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- The Official Book of Ultima, page 78

- "Richard Garriott interview on G4TV". G4tv.com. Retrieved 2011-11-10.

- The Official Book of Ultima, page 23

- The Official Book of Ultima by Shay Addams

- Ultima V game and documentation

- Ultima VI game and documentation

- Ultima VII game and documentation

- Ultima VII Part 2 Serpent Isle game and documentation

- McCubbin, Chris and David Ladyman (1999). Prima's Official Guide to Ultima Ascension. Rocklin, CA: Prima Publishing. pp. 254–264. ISBN 0-7615-1585-2.

- Ferrell, Keith (January 1989). "Dungeon Delving with Richard Garriott". Compute!. p. 16. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- Brad King and John Borland (2003). Dungeons and Dreamers. McGraw-Hill/Osborne., cited in Howard, Jeff (2008-09-01). Quests: Design, Theory, and History in Games and Narratives. A K Peters/CRC Press. pp. 16, 21, 30–36, 58. ISBN 978-1-56881-347-9.

- Addams, Shay (1990). The Official Book of Ultima. Greensboro, NC: COMPUTE Books. p. 254. ISBN 0-87455-228-1.

- "Inside Ultima IV". Computer Gaming World. March 1986. pp. 18–21.

- Lord Blackthorn's Code of Virtues

- See "Gargish Virtues Archived 2011-05-05 at the Wayback Machine" at the Ultima Codex

- Kline, Stephen; Dyer-Witherford, Nick; De Peuter, Greig (2003-07-31). Digital Play: The Interaction of Technology, Culture and Marketing. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 160–162. ISBN 978-0-7735-2591-7.

- Hayse, Mark (2010-01-01). "Ultima IV: Simulating the Religious Guest". In Craig Detweiler (ed.). Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games With God. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 34–46. ISBN 978-0-664-23277-1.

- Brown, Harry (2008-09-01). Videogames and Education. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 82, 88–90. ISBN 978-0-7656-1997-6.

- Next Generation 21 (September 1996), p.51.

- "Top 50 Games of All Time". Next Generation. No. 50. Imagine Media. February 1999. p. 78.

- "The Ten Best Gameworlds: Britannia (Ultima series) | GameSpot". Web.archive.org. 2004-10-27. Archived from the original on March 18, 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- Ferrell, Keith (November 1990). "The Japan Factor". Compute! (123): 22–29.

- Barton 2007, p. 4

- Barton 2007, p. 76

- King & Borland 2003, pp. 72–78

- Vestal 1998, p. "The First Console RPG" "A devoted gamer could make a decent case for either of these Atari titles founding the RPG genre; nevertheless, there's no denying that Dragon Quest was the primary catalyst for the Japanese console RPG industry. And Japan is where the vast majority of console RPGs come from, to this day. Influenced by the popular PC RPGs of the day (most notably Ultima), both Excalibur and Dragon Quest "stripped down" the statistics while keeping features that can be found even in today's most technologically advanced titles. An RPG just wouldn't be complete, in many gamers' eyes, without a medieval setting, hit points, random enemy encounters, and endless supplies of gold. (...) The rise of the Japanese RPG as a dominant gaming genre and Nintendo's NES as the dominant console platform were closely intertwined."

- Gerblick, Jordan. "Ultima remasters were turned down by EA, says series creator Richard Garriott". GamesRadar. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Reahard, Jef (2011-12-12). "Garriott's Ultimate RPG 'clearly the spiritual successor' to Ultima | Massively". Massively.joystiq.com. Archived from the original on 2013-12-11. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- "Shroud of the Avatar Kickstarter Campaign". Portalarium. 2013-04-08. Retrieved 2013-04-08.

- "Shroud of the Avatar Home Page". Portalarium. 2013-04-08. Retrieved 2013-04-08.

- Portalarium Austin (2017-03-17), Spring 2017 Telethon of the Avatar, retrieved 2017-03-22

- "Shroud of the Avatar FAQ". Portalarium. 2015. Retrieved 2015-04-13.

Notes

- Addams, Shay (December 1992). The Official Book of Ultima. COMPUTE Books. ISBN 978-0-87455-264-5.

- Barton, Matt (2007-02-23). "The History of Computer Role-Playing Games Part 1: The Early Years (1980–1983)". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- King, Brad; Borland, John M. (2003). Dungeons and Dreamers: The Rise of Computer Game Culture from Geek to Chic. McGraw-Hill/Osborne. ISBN 0-07-222888-1. Retrieved 2010-09-25.

- Vestal, Andrew (1998-11-02). "The History of Console RPGs". GameSpot. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ultima |

- Origin Systems, Inc. (redirects to the Ultima Online website)

- The official Ultima WWW Archive – Information and files concerning the entire saga

- Ultima series at MobyGames

- The Ultima Legacy from GameSpot – A historical overview of the series

- The Codex of Ultima Wisdom (Ultima Wiki)