Sorting network

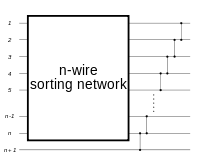

In computer science, comparator networks are abstract devices built up of a fixed number of "wires", carrying values, and comparator modules that connect pairs of wires, swapping the values on the wires if they are not in a desired order. Such networks are typically designed to perform sorting on fixed numbers of values, in which case they are called sorting networks.

Sorting networks differ from general comparison sorts in that they are not capable of handling arbitrarily large inputs, and in that their sequence of comparisons is set in advance, regardless of the outcome of previous comparisons. This independence of comparison sequences is useful for parallel execution and for implementation in hardware. Despite the simplicity of sorting nets, their theory is surprisingly deep and complex. Sorting networks were first studied circa 1954 by Armstrong, Nelson and O'Connor,[1] who subsequently patented the idea.[2]

Sorting networks can be implemented either in hardware or in software. Donald Knuth describes how the comparators for binary integers can be implemented as simple, three-state electronic devices.[1] Batcher, in 1968, suggested using them to construct switching networks for computer hardware, replacing both buses and the faster, but more expensive, crossbar switches.[3] Since the 2000s, sorting nets (especially bitonic mergesort) are used by the GPGPU community for constructing sorting algorithms to run on graphics processing units.[4]

Introduction

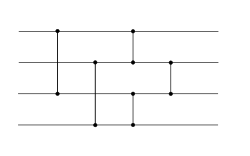

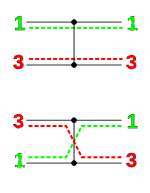

A sorting network consists of two types of items: comparators and wires. The wires are thought of as running from left to right, carrying values (one per wire) that traverse the network all at the same time. Each comparator connects two wires. When a pair of values, traveling through a pair of wires, encounter a comparator, the comparator swaps the values if and only if the top wire's value is greater than the bottom wire's value.

In a formula, if the top wire carries x and the bottom wire carries y, then after hitting a comparator the wires carry and , respectively, so the pair of values is sorted.[5]:635 A network of wires and comparators that will correctly sort all possible inputs into ascending order is called a sorting network.

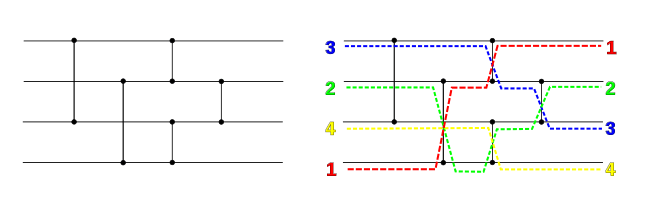

The full operation of a simple sorting network is shown below. It is easy to see why this sorting network will correctly sort the inputs; note that the first four comparators will "sink" the largest value to the bottom and "float" the smallest value to the top. The final comparator simply sorts out the middle two wires.

Depth and efficiency

The efficiency of a sorting network can be measured by its total size, meaning the number of comparators in the network, or by its depth, defined (informally) as the largest number of comparators that any input value can encounter on its way through the network. Noting that sorting networks can perform certain comparisons in parallel (represented in the graphical notation by comparators that lie on the same vertical line), and assuming all comparisons to take unit time, it can be seen that the depth of the network is equal to the number of time steps required to execute it.[5]:636–637

Insertion and Bubble networks

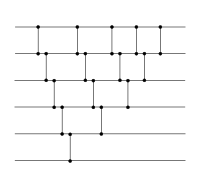

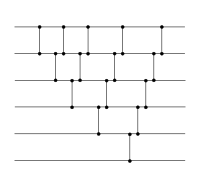

We can easily construct a network of any size recursively using the principles of insertion and selection. Assuming we have a sorting network of size n, we can construct a network of size n + 1 by "inserting" an additional number into the already sorted subnet (using the principle behind insertion sort). We can also accomplish the same thing by first "selecting" the lowest value from the inputs and then sort the remaining values recursively (using the principle behind bubble sort).

A sorting network constructed recursively that first sorts the first n wires, and then inserts the remaining value. Based on insertion sort |

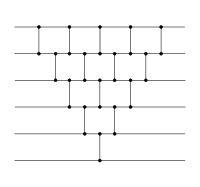

The structure of these two sorting networks are very similar. A construction of the two different variants, which collapses together comparators that can be performed simultaneously shows that, in fact, they are identical.[1]

Bubble sorting network |

Insertion sorting network |

When allowing for parallel comparators, bubble sort and insertion sort are identical |

The insertion network (or equivalently, bubble network) has a depth of 2n - 3[1], where n is the number of values. This is better than the O(n log n) time needed by random-access machines, but it turns out that there are much more efficient sorting networks with a depth of just O(log2 n), as described below.

Zero-one principle

While it is easy to prove the validity of some sorting networks (like the insertion/bubble sorter), it is not always so easy. There are n! permutations of numbers in an n-wire network, and to test all of them would take a significant amount of time, especially when n is large. The number of test cases can be reduced significantly, to 2n, using the so-called zero-one principle. While still exponential, this is smaller than n! for all n ≥ 4, and the difference grows rapidly with increasing n.

The zero-one principle states that, if a sorting network can correctly sort all 2n sequences of zeros and ones, then it is also valid for arbitrary ordered inputs. This not only drastically cuts down on the number of tests needed to ascertain the validity of a network, it is of great use in creating many constructions of sorting networks as well.

The principle can be proven by first observing the following fact about comparators: when a monotonically increasing function f is applied to the inputs, i.e., x and y are replaced by f(x) and f(y), then the comparator produces min(f(x), f(y)) = f(min(x, y)) and max(f(x), f(y)) = f(max(x, y)). By induction on the depth of the network, this result can be extended to a lemma stating that if the network transforms the sequence a1, ..., an into b1, ..., bn, it will transform f(a1), ..., f(an) into f(b1), ..., f(bn). Suppose that some input a1, ..., an contains two items ai < aj, and the network incorrectly swaps these in the output. Then it will also incorrectly sort f(a1), ..., f(an) for the function

This function is monotonic, so we have the zero-one principle as the contrapositive.[5]:640–641

Constructing sorting networks

Various algorithms exist to construct simple, yet efficient sorting networks of depth O(log2 n) (hence size O(n log2 n)) such as Batcher odd–even mergesort, bitonic sort, Shell sort, and the Pairwise sorting network. These networks are often used in practice. It is also possible, in theory, to construct networks of logarithmic depth for arbitrary size, using a construction called the AKS network, after its discoverers Ajtai, Komlós, and Szemerédi.[6] While an important theoretical discovery, the AKS network has little or no practical application because of the linear constant hidden by the Big-O notation, which is in the "many, many thousands".[5]:653 These are partly due to a construction of an expander graph. A simplified version of the AKS network was described by Paterson, who notes that "the constants obtained for the depth bound still prevent the construction being of practical value".[7] Another construction of sorting networks of size O(n log n) was discovered by Goodrich.[8] While their size has a much smaller constant factor than that of AKS networks, their depth is O(n log n), which makes them inefficient for parallel implementation.

Optimal sorting networks

For small, fixed numbers of inputs n, optimal sorting networks can be constructed, with either minimal depth (for maximally parallel execution) or minimal size (number of comparators). These networks can be used to increase the performance of larger sorting networks resulting from the recursive constructions of, e.g., Batcher, by halting the recursion early and inserting optimal nets as base cases.[9] The following table summarizes the optimality results for small networks for which the optimal depth is known:

| n | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depth[10] | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 |

| Size, upper bound[11] | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 12 | 16 | 19 | 25 | 29 | 35 | 39 | 45 | 51 | 56 | 60 | 71 |

| Size, lower bound (if different)[12] | 43 | 47 | 51 | 55 | 60 |

For larger networks neither the optimal depth nor the optimal size are currently known. The bounds known so far are provided in the table below:

| n | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depth, upper bound[10][13][14] | 11 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| Depth, lower bound[10] | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Size, upper bound[14] | 77 | 85 | 91 | 100 | 107 | 115 | 120 | 132 | 139 | 150 | 155 | 165 | 172 | 180 | 185 |

| Size, lower bound[12] | 65 | 70 | 75 | 80 | 85 | 90 | 95 | 100 | 105 | 110 | 115 | 120 | 125 | 130 | 135 |

The first sixteen depth-optimal networks are listed in Knuth's Art of Computer Programming,[1] and have been since the 1973 edition; however, while the optimality of the first eight was established by Floyd and Knuth in the 1960s, this property wasn't proven for the final six until 2014[15] (the cases nine and ten having been decided in 1991[9]).

For one to eleven inputs, minimal (i.e. size-optimal) sorting networks are known, and for higher values, lower bounds on their sizes S(n) can be derived inductively using a lemma due to Van Voorhis[1] (p. 240): S(n) ≥ S(n − 1) + ⌈log2n⌉. The first ten optimal networks have been known since 1969, with the first eight again being known as optimal since the work of Floyd and Knuth, but optimality of the cases n = 9 and n = 10 took until 2014 to be resolved.[11] An optimal network for size 11 was found in December of 2019 by Jannis Harder, which also made the lower bound for 12 match its upper bound.[16]

Some work in designing optimal sorting network has been done using genetic algorithms: D. Knuth mentions that the smallest known sorting network for n = 13 was found by Hugues Juillé in 1995 "by simulating an evolutionary process of genetic breeding"[1] (p. 226), and that the minimum depth sorting networks for n = 9 and n = 11 were found by Loren Schwiebert in 2001 "using genetic methods"[1] (p. 229).

Complexity of testing sorting networks

It is unlikely that significant further improvements can be made for testing general sorting networks, unless P=NP, because the problem of testing whether a candidate network is a sorting network is known to be co-NP-complete.[17]

References

- Knuth, D. E. (1997). The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 3: Sorting and Searching (Second ed.). Addison–Wesley. pp. 219–247. ISBN 978-0-201-89685-5. Section 5.3.4: Networks for Sorting.

- US 3029413, O'Connor, Daniel G. & Raymond J. Nelson, "Sorting system with n-line sorting switch", published 10 April 1962

- Batcher, K. E. (1968). Sorting networks and their applications. Proc. AFIPS Spring Joint Computer Conference. pp. 307–314.

- Owens, J. D.; Houston, M.; Luebke, D.; Green, S.; Stone, J. E.; Phillips, J. C. (2008). "GPU Computing". Proceedings of the IEEE. 96 (5): 879–899. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2008.917757.

- Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L. (1990). Introduction to Algorithms (1st ed.). MIT Press and McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-262-03141-8.

- Ajtai, M.; Komlós, J.; Szemerédi, E. (1983). An O(n log n) sorting network. STOC '83. Proceedings of the fifteenth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing. pp. 1–9. doi:10.1145/800061.808726. ISBN 0-89791-099-0.

- Paterson, M. S. (1990). "Improved sorting networks with O(log N) depth". Algorithmica. 5 (1–4): 75–92. doi:10.1007/BF01840378.

- Goodrich, Michael (March 2014). Zig-zag Sort: A Simple Deterministic Data-Oblivious Sorting Algorithm Running in O(n log n) Time. Proceedings of the 46th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing - STOC '14. pp. 684–693. arXiv:1403.2777. doi:10.1145/2591796.2591830. ISBN 9781450327107.

- Parberry, Ian (1991). "A Computer Assisted Optimal Depth Lower Bound for Nine-Input Sorting Networks" (PDF). Mathematical Systems Theory. 24: 101–116. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.712.219. doi:10.1007/bf02090393.

- Codish, Michael; Cruz-Filipe, Luís; Ehlers, Thorsten; Müller, Mike; Schneider-Kamp, Peter (2015). Sorting Networks: to the End and Back Again. arXiv:1507.01428. Bibcode:2015arXiv150701428C.

- Codish, Michael; Cruz-Filipe, Luís; Frank, Michael; Schneider-Kamp, Peter (2014). Twenty-Five Comparators is Optimal when Sorting Nine Inputs (and Twenty-Nine for Ten). Proc. Int'l Conf. Tools with AI (ICTAI). pp. 186–193. arXiv:1405.5754. Bibcode:2014arXiv1405.5754C.

- Obtained by Van Voorhis lemma and the value S(11) = 35

- Ehlers, Thorsten (February 2017). "Merging almost sorted sequences yields a 24-sorter". Information Processing Letters. 118. doi:10.1016/j.ipl.2016.08.005.

- Dobbelaere, Bert. "SorterHunter". GitHub. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- Bundala, D.; Závodný, J. (2014). Optimal Sorting Networks. Language and Automata Theory and Applications. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 8370. pp. 236–247. arXiv:1310.6271. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-04921-2_19. ISBN 978-3-319-04920-5.

- Harder, Jannis. "sortnetopt". GitHub. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- Parberry, Ian (1991). On the Computational Complexity of Optimal Sorting Network Verification. Proc. PARLE '91: Parallel Architectures and Languages Europe, Volume I: Parallel Architectures and Algorithms, Eindhoven, The Netherlands. pp. 252–269.

- O. Angel, A.E. Holroyd, D. Romik, B. Virag, Random Sorting Networks, Adv. in Math., 215(2):839–868, 2007.

External links

- Sorting Networks

- Sorting Networks

- Tool for generating and graphing sorting networks

- Sorting networks and the END algorithm

- Lipton, Richard J.; Regan, Ken (24 April 2014). "Galactic Sorting Networks". Gödel’s Lost Letter and P=NP.

- Sorting Networks validity