Soldier Blue

Soldier Blue is a 1970 American Revisionist Western film directed by Ralph Nelson and starring Candice Bergen, Peter Strauss, and Donald Pleasence. Adapted by John Gay from the novel Arrow in the Sun by T.V. Olsen, it is inspired by events of the 1864 Sand Creek massacre in the Colorado Territory. Nelson and Gay intended to utilize the narrative surrounding the Sand Creek massacre as an allegory for the contemporary Vietnam War.[3]

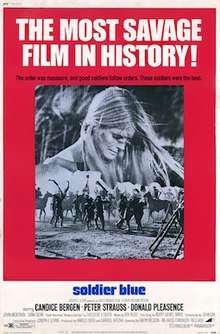

| Soldier Blue | |

|---|---|

Original theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Ralph Nelson |

| Produced by | Gabriel Katzka Harold Loeb |

| Screenplay by | John Gay |

| Based on | Arrow in the Sun by Theodore V. Olsen |

| Starring | Candice Bergen Peter Strauss Donald Pleasence |

| Music by | Roy Budd |

| Cinematography | Robert B. Hauser |

| Edited by | Alex Beaton |

Production company | Katzka-Loeb |

| Distributed by | Embassy Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 115 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $1.2 million (North American rentals)[2] |

Released in August 1970, the film drew attention for its frank depictions of violence, specifically its graphic final sequence. Some film scholars have cited Soldier Blue as a critique of America's "archetypal art form [the Western]," with other interpretations ranging from it being an anti-war picture to an exploitation film.[4]

Plot

In 1877 Colorado Territory, a young woman, Cresta Lee, and young U.S. Private Honus Gant are joined together by fate when they are the only two survivors after their group is massacred by the Cheyenne. Gant is devoted to his country and duty; Lee, who has lived with the Cheyenne for two years, is scornful of Gant (she refers to him as "Soldier Blue" derisively) and declares that in this conflict she sympathizes with them. The two must now try to make it to Fort Reunion, the army camp, where Cresta's fiancé, an army officer, waits for her. As they travel through the desert with very low supplies, hiding from the Indians, they are spotted by a group of Kiowa horsemen. Under pressure from Cresta, Honus fights and seriously wounds the group's chief. Honus finds himself unable to kill the chief and the chief's own men stab him for his defeat and leave Honus and Cresta alone. The ideological gulf between them is also revealed in their attitudes towards societal mores, with the almost-puritanical Honus disturbed by things Cresta barely notices.

Eventually, after being pursued by a Jewish trader named Isaac Cumber, who sells guns to the Cheyenne, but whose latest shipment of weapons Honus has destroyed, Honus finds himself in a cave where Cresta has left him to get help. She arrives at Fort Reunion, only to discover that her fiancé's cavalry unit plans to attack the peaceful Indian village of the Cheyenne the following day. She runs away on a horse and reaches the village in time to warn Spotted Wolf, the Cheyenne chief. The chief does not recognize the danger and, using the U.S. flag, rides out to extend a hand of friendship to the American soldiers. The soldiers, however, obey the orders of their commanding officer to open fire on the village.

After a cavalry charge decimates the Indian men, the soldiers enter the village and begin to rape and kill the female survivors. Honus protests and attempts to disrupt the massacre, to no avail. Cresta attempts to lead the remaining women and children to safety, but her group is discovered and massacred, though Cresta herself survives. After the battle, Honus is led away in shackles and Cresta departs with the remaining few survivors.

Cast

- Candice Bergen as Kathy Maribel 'Cresta' Lee

- Peter Strauss as Honus Gant

- Donald Pleasence as Isaac Q. Cumber

- John Anderson as Colonel Iverson

- Jorge Rivero as Spotted Wolf

- Dana Elcar as Captain Battles

- Bob Carraway as Lieutenant McNair

- Martin West as Lieutenant Spingarn

- James Hampton as Private Menzies

- Mort Mills as Sergeant O'Hearn

- Jorge Russek as Running Fox

- Ralph Nelson (credited as Alf Elson) as Agent Long

Production

The film provided the first motion picture account of the Sand Creek massacre, one of the most infamous incidents in the history of the American frontier, in which Colorado Territory militia under Colonel John M. Chivington massacred a defenseless village of Cheyenne and Arapaho on the Colorado Eastern Plains.

The account of the massacre is included as part of a longer fictionalized story about the escape of two white survivors from an earlier massacre of U.S. Cavalry troops by Cheyenne, and names of the actual historical characters were changed. Director Nelson stated that he was inspired to make the film based on the wars in Vietnam and Songmy.[5]

Principal photography began on October 28, 1969, with exterior photography taking place in Mexico.[1] Arthur Ornitz was originally hired as the film's cinematographer, but was replaced by Robert B. Hauser several weeks into production.[1] According to actress Bergen, a large van full of prosthetics was brought in during the filming of the violent battle sequences, full of dummy body parts and animatronics.[6] Additionally, amputees from Mexico City were hired to serve as extras during the final massacre sequence.[6]

Release

Soldier Blue premiered in New York City on August 12, 1970, and opened in Los Angeles two days later on August 14, 1970.[1]

Box office

The film was the third-most popular film at the British box office in 1971.[7] It brought $1.2 million from the U.S./ Canada rentals.[2] The title song, written and performed by Buffy Sainte-Marie, was released as a single and became a top ten hit in the UK as well as other countries in Europe and Japan during the summer of 1971.[8]

Reception

Contemporaneous

Multiple film critics said Soldier Blue evoked the My Lai massacre, which had been disclosed to the American public the previous year.[9] In September 1970, Dotson Rader writing in The New York Times, remarked that Soldier Blue "must be numbered among the most significant, the most brutal and liberating, the most honest American films ever made."[5]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times wrote of the film: "Soldier Blue is indeed savage, but it wears its cloak of "truth" self-consciously. It is supposed to be a pro-Indian movie, and at the end the camera tells us the story was true, more or less, and that the Army chief of staff himself called the massacre shown in the film one of the most shameful moments in American history."[10] He added: "So it was, and of course we're supposed to make the connection with My Lai and take Soldier Blue as an allegory for Vietnam. But that just won't do. The film is too mixed up to qualify as a serious allegory about anything."[10] The Time Out film guide called the film "a grimly embarrassing anti-racist Western about the U.S. Cavalry's notorious Sand Creek Indian massacre in 1864. In the interests of propaganda, one might just about stomach the way the massacre itself is turned into a gleefully exploitative gore-fest of blood and amputated limbs; but not when it's associated with a desert romance that's shot like an ad-man's wet dream, all soft focus and sweet nothings."[11]

Contemporary

Modern critics and scholars have alternately described Soldier Blue as a revisionist western[12] "anti-American,"[13] and as an exploitation film.[4] In 2004, the BBC named it "one of the most significant American films ever made."[14] British author and critic P.B. Hurst, who wrote the 2008 book The Most Savage Film: Soldier Blue, Cinematic Violence and the Horrors of War, said of the film:[15]

A good number of critics in 1970 believed that Soldier Blue had set a new mark in cinematic violence, as a result of its graphic scenes of Cheyenne women and children being slaughtered, and had thus lived up – or down – to its U.S. poster boast that it was "The Most Savage Film in History." A massive hit in Great Britain and much of the rest of the world, Soldier Blue was, in the words of its maverick director, Ralph Nelson, "not a popular success" in the United States. This probably had less to do with the picture's groundbreaking violence, and more to do with the fact that it was the U.S. Cavalry who were breaking new ground. For Nelson's portrayal of the boys in blue as blood crazed maniacs, who blow children's brains out and women, shattered for ever one of America's most enduring movie myths – that of the cavalry as good guys riding to the rescue – and rendered Soldier Blue one of the most radical films in the history of American cinema. The film's failure in its homeland might also have had something to do with the perception in some quarters – prompted by production company publicity material – that it was a deliberate Vietnam allegory.

Retrospective analysis has placed the film in a tradition of motion pictures of the early 1970s – such as Ulzana's Raid (1972) – which were used as "natural venues for remarking on the killing of women and children by American soldiers" in light of the political conflicts of the era.[16] However, the "visual excesses" of the film's most violent sequences have been similarly criticized as exploitative by modern critics as well.[17]

In a 2005 article on the film in Uncut, Kevin Maher deemed it "a bloody 1970 exploitation western ... [which] has a gore-count worthy of Cannibal Holocaust."[4] TV Guide awarded the film one out of five stars, writing: "Soldier Blue suffers from Bergen's weak performance and Strauss is bland, but the parallel between the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre and Vietnam's My Lai incident is disturbing and the film's depiction of Native American life is an explicite attempt to move past Hollywood stereotypes."[18]

Film scholar Christopher Frayling described Soldier Blue as a "much more angry film" than its contemporary Westerns, which "challenges the language of the traditional Western at the same time as its ideological bases."[19] Frayling also praised its cinematography and visual elements in his 2006 book Spaghetti Westerns: Cowboys and Europeans from Karl May to Sergio Leone: "most critics succeeded in missing the really inventive sections of Soldier Blue, which involve Nelson's use of elaborate zooms, and of untraditional compositions, both of which subtly explore the relationship between the 'initiates' and the virgin land which surrounds them."[19]

Recalling the film, star Candice Bergen commented that it was "a movie whose heart, if nothing else, was in the right place."[6]

In Culture

The following quote appears, along with other figures and images, on the 2010 work “Soldier Blue” (various visual art mediums on paper) by artist Andrea Carlson: “Due to the controversial and devastating nature of SOLDIER BLUE the management of this theatre will not allow patrons to enter after the film has begun. Thank you for your cooperation.”

See also

References

- "Soldier Blue (1970)". American Film Institute Catalog. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- "Big Rental Films of 1970". Variety. January 6, 1971. p. 11.

- Maddrey 2016, p. 160.

- Hurst 2008, p. 2.

- The New York Times Film Reviews 1970–1971. The New York Times. 1971. p. 218.

- Maddrey 2016, p. 116.

- Waymark, Peter (December 30, 1971). "Richard Burton top draw in British cinemas". The Times. London.

- "Soldier Blue Video – Lyrics". Buffy Sainte-Marie (blog). August 7, 2011. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- Huebner 2008, p. 251.

- Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1970). "Soldier Blue". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved March 28, 2018 – via RogerEbert.com.

- "Soldier Blue (1970)". Time Out. London. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- Indick 2008, p. 48.

- Maddrey 2016, p. 125.

- Hurst 2008, p. 1.

- Hurst, P.B. "The Most Savage Film: Reliving Soldier Blue". Cinema Retro. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- Huebner 2008, p. 250.

- Huebner 2008, p. 252.

- "Soldier Blue". TV Guide. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- Frayling 2006, p. 283.

Works cited

- Frayling, Christopher (2006). Spaghetti Westerns: Cowboys and Europeans from Karl May to Sergio Leone. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-845-11207-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Huebner, Andrew J. (2008). The Warrior Image: Soldiers in American Culture from the Second World War to the Vietnam Era. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-807-83144-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hurst, P.B. (2008). The Most Savage Film: Soldier Blue, Cinematic Violence and the Horrors of War. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3710-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Indick, William (2008). The Psychology of the Western: How the American Psyche Plays Out on Screen. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-786-43460-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Maddrey, Joseph (2016). The Quick, the Dead and the Revived: The Many Lives of the Western Film. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-1-476-62549-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)