Socialist League of Malawi

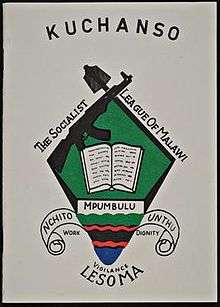

The Socialist League of Malawi (LESOMA) was a political party officially founded in 1974 in Tanzania by exiled Malawians. Its then self-declared goals were to re-establish the honor of Malawi, its legitimate place in the Organisation of African Unity and in the United Nations and especially to secure that Malawi would play an active role in the advancement of the African revolution and international solidarity.

Socialist League of Malawi (LESOMA) | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) | |

| Leader | Yatuta Chisiza (1964-1967) Attati Mpakati (1967-1983) |

| Founded | 1964 (alleged[1]) 1974 (officially) |

| Headquarters | Dar es Salaam |

| Ideology | Communism Pan-Africanism |

Foundation and Political Leadership

Documented information about this party is rare; it was not only founded in exile but also ceased to exist there. However, beside the self-declaration quoted above a self-portrayal of LESOMA from the estate of one of the members of its steering committee, Mahoma Mwaungulu, further states that its emergence was the result of a dispute in Tanzania between Yatuta Chisiza, who had studied in China, and Masauko Chipembere yet in the second half of the 1960th.[2] Both were former ministers in the first Malawian cabinet who had to escape from their newly independent home country because of the violent repressions ordered by Hastings Banda following the Cabinet Crisis of 1964. After the dispute with Chipembere, Chisiza decided to start a guerilla campaign in Malawi with less than 20 men.[3] Of the five survivors, two later belonged to the steering committee of LESOMA. Chisiza, who also died in the guerilla campaign, was followed by Attati Mpakati as the new head of LESOMA. Files of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) mention his academic formation in the Soviet Union.;[4] however, a British newspaper article speaks of studies in Moscow, Sweden and even the Federal Republic of Germany.[5] Like his precursor, Mkapati was first severely injured by a letter bomb sent from Banda in 1979 to Mozambique and later, after having left Zambia in 1982 due to the pressure Hastings Banda put on the Zambian government, felt victim of another strike in Zimbabwe in 1983. It is suspected that yet before Hastings Banda had put similar pressure on the Tanzania of Julius Nyerere to force LESOMA moving its headquarter from Dar es Salaam to another country.

Internal Structure

The party seemed to have been formed in its majority by exiles from the Northern part of Malawi. This led to internal critic documented in a letter sent to Mwaungulu by another Malawian who, during the time the letter was written, studied in Sweden and met with a high ranked LESOMA member in Norway in 1985 with whom he talked about that matter. Another critic raised by him was the complete absence of women in the steering committee. A German specialist on Malawian political history roughly estimates that the total number of LESOMA members was several thousands.[6] He also regards LESOMA as the most important Malawian party opposed to the dictatorship of Hastings Banda.[7]

International Solidarity and Political Legacy

From 1975 until 1978 LESOMA received some support from the GDR. This support included a one-year journalistic training in the GDR of two members of LESOMA and the printing of 1500 copies of Kuchanso, a political journal used for propaganda in the Frontline States and Malawi.[8] Two other socialist countries said to have supported LESOMA are the Soviet Union and Cuba. The party existed until 1991 when LESOMA, together with two other Malawian opposition parties, formed the United Front for Multiple Democracy. Arguably the greatest achievement of LESOMA is that its mere existence rewrites Malawian history; as the most radical party of the deterritorialized Malawian opposition under the Western sponsored dictatorship of Hastings Banda it links Malawi to the African struggle against Apartheid and Neocolonialism during the Cold War.

References

- (PDF) http://ngomamotovibes.com/chiume/CABINETCRISIS1964.pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - SAPMO-BArchiv, DZ 8/186, "Die sozialistische Liga Malawis"

- Baker 2001: 279 ff

- SAPMO-BArchiv, DZ 8/186, „Die sozialistische Liga Malawis“

- The Guardian, 12-24-1979

- Meinhardt 1997: 98

- Meinhardt 1993: 61

- Pampuch 2013: 157

Literature

- Baker, Colin (2001): Revolt of the Ministers. The Malawi Cabinet Crisis, 1964-1965. London/New York

- Meinhardt, Heiko (1993): Die Rolle des Parliaments im autoritären Malawi. Hamburg

- Meinhardt, Heiko: (1997): Politische Transition und Demokratisierung in Malawi. Hamburg

- Searle, Chris: Struggling against the "Bandastan": an interview with Attati Mpakati. Race & Class 1980, 21: 389-401

- Stiftung Archiv der Parteien und Massenorganisationen der DDR im Bundesarchiv (SAPMO-BArchiv): DZ 8/186, „Beziehungen zur Malawi-Liga 1975-1980“

- Pampuch, Sebastian: "Ein malawischer Exilant im geteilten Berlin: Mahoma Mwakipunda Mwaungulu." In: Diallo, Oumar/Zeller, Joachim (ed.): Black Berlin. Die deutsche Metropole und ihre afrikanische Diaspora in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Metropol-Verlag Berlin 2013, p. 151-157