Siward Barn

Siward Barn (Old English: Sigeweard Bearn) was an 11th-century English thegn and landowner-warrior. He appears in the extant sources in the period following the Norman Conquest of England, joining the northern resistance to William the Conqueror by the end of the 1060s. Siward's resistance continued until his capture on the Isle of Ely alongside Æthelwine, Bishop of Durham, Earl Morcar, and Hereward ("the Wake") as cited in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Siward and his confiscated properties in central and northern England were mentioned in Domesday Book, and from this it is clear that he was one of the main antecessors of Henry de Ferrers, father of Robert de Ferrers, the first Earl of Derby.

Sigeweard Bear | |

|---|---|

| Occupation | Thegn and landowner-warrior |

| Years active | 1066–1087 |

| Known for | Fighting against William the Conqueror |

Following his capture in 1071, he was imprisoned. This incarceration lasted until 1087, when a guilt-ridden King William, in expectation of his own death, ordered Siward's release. Firm evidence of Siward's later life is non-existent, but some historians have argued that he took up a career in the Varangian Guard at Constantinople, in the service of the Emperor Alexios I Komnenos. The sources upon which this theory is based also allege that Siward led a party of English colonists to the Black Sea, who renamed their conquered territory New England.

Origins

Identifying Siward's origin is difficult for historians because of the large number of Siwards in England in the mid-11th century. Other notable Siwards include Siward of Maldon and Siward Grossus, both men of substance with landholdings larger or comparable to Siward Barn's.[1] The Anglo-Norman writer Orderic Vitalis, when describing William the Conqueror's stay at Barking, says that Morcar, formerly Earl of Northumbria, and Edwine, Earl of Mercia, came and submitted to King William, followed by Copsi, Earl of Northumbria, along with Thurkil of Limis, Eadric the Wild, and "Ealdred and Siward, the sons of Æthelgar, grandsons [or grand-nephews] (pronepotes) of King Edward".[2]

Edward Augustus Freeman and other historians have thought that this Siward was Siward Barn, arguing that Siward must have been a descendant of Uhtred the Bold, Earl of Northumbria, and Ælfgifu, daughter of King Æthelred the Unready, King Edward's father.[3] Historian and translator of Orderic, Marjorie Chibnall, pointed out that this Siward is mentioned later in his Ecclesiastical History as a Shropshire landowner, in connection with the foundation of Shrewsbury Abbey.[4] Ann Williams likewise rejected this identification, identifying this Siward firmly with the Shropshire thegn Siward Grossus.[5] According to Williams' reconstruction, Siward Grossus and his brother Ealdred were the sons of Æthelgar by a daughter of Eadric Streona, Ealdorman of Mercia and Eadgyth, another daughter of King Æthelred, explaining the relationship Orderic believed they had with Edward the Confessor.[6]

Another historian, Forrest Scott, guessed that Siward was a member of the family of Northumbrian earls, presumably connected in some way to Siward, Earl of Northumbria.[7] Margaret Faull and Marie Stinson, the editors of the Philimore Domesday Book for Yorkshire, believed that Siward was "a senior member of the house of Bamburgh and possibly a brother or half-brother of Earl Gospatric".[8] Another historian, Geoffrey Barrow, pointed out that Faull and Stinson gave no evidence for this assertion, and doubted the hypothesis because of Siward's Danish name.[9]

From York to Ely

In 1068, there was a revolt in the north of England against the rule of King William, few details of which are recorded.[10] It was serious enough to worry King William, who marched north and began the construction of castles at Warwick, Nottingham, York, Lincoln, Huntingdon and Cambridge.[11] Earl Cospatric apparently fled to Scotland and in the beginning of 1069 King William appointed the Picard Robert de Comines as the new earl of Northumbria.[12]

During the winter the English murdered Earl William and Robert fitz Richard, the custodian of the new castle at York, and trapped William Malet, the first Norman sheriff of York, in the castle.[13] King William went north in the spring or summer of 1069, relieved the siege of Malet, and restored the castle, placing William fitz Osbern in charge.[14] The leaders of the revolt were Edgar the Ætheling (claimant to the English throne), Gospatric of Northumbria, and, among others, Mærle-Sveinn, former sheriff of Lincoln, and many senior Northumbria nobles.[15]

In the autumn of 1069, a fleet under the Danish king Sweyn Estridsson and his brother Earl Osbjorn arrived off the coast of England.[16] It is from this point that Siward's involvement in the revolt is documented. Orderic Vitalis related that:

The Ætheling, Waltheof, Siward, and the other English leaders had joined the Danes ... The Danes reached York, and a general rising of the inhabitants swelled their ranks. Waltheof, Gospatric (Gaius Patricius), Mærle-Sveinn (Marius Suenus), Elnoc, Arnketil, and the four sons of Karle were in the advance guard and led the Danish and Norwegian forces.[17]

What followed was William's most devastating punitive expedition, the so-called "Harrying of the North", conducted during the winter of 1069/70.[18] After two minor engagements disadvantageous to the Danes, King William came to an agreement with Earl Osbjorn that neutralised them.[19] William held Christmas court at the ruined city of York, and brought Waltheof and Gospatric back into his peace at the River Tees.[20]

Siward was at Wearmouth in the summer of 1070, with Edgar and Mærle-Sveinn, while William marched to the River Tyne with his marauding army. Although William burnt down the church of Jarrow, he left Edgar's party undisturbed.[21] Siward must have gone to Scotland in this year, for the Historia Regum reports that in 1071 Morcar (previously earl of Northumbria) and Hereward went by ship to the Isle of Ely, and that "Æthelwine, bishop of Durham, and Siward, nicknamed Barn, sailing back from Scotland" arrived there too.[22] This is also related by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which confirms that:

Bishop Æthelwine and Siweard Bearn came to Ely and many hundred men with them".[23]

It was at Ely that Siward and all the other notables, save Hereward, were captured by King William.[24]

Confiscation and release

By 1086, perhaps soon before or after his capture, many of Siward's lands were given to the Norman warrior Henry de Ferrers, though other successors included Geoffrey de La Guerche and William d'Ecouis.[25] According to the Domesday Book, in "the time of Edward" (TRE), or rather on the day of the death of Edward the Confessor, Siward held twenty-one manors in eight different English counties.[26]

In Berkshire, Greenham (£8), Lockinge (£10) and Stanford in the Vale (£30; now in Oxfordshire); in Gloucestershire, Lechlade (£20); in Warwickshire, Grendon (£2), Burton Hastings (£4) and Harbury (£2); in Derbyshire, Brassington (£6), Croxhall (£3), Catton (£3), Cubley (£5), Norbury and Roston (£5), Duffield (£9), Breadhall (£4), "Wormhill" (waste) and Moreley (waste); in Nottinghamshire, Leake (£6) and Bonnington (s. 6); in Yorkshire Adlingfleet (£4); in Lincolnshire, Whitton (£10) and Haxey (5); and in Norfolk Sheringham (£4) and Salthouse (£2).[26] Ann Williams doubted that the estates in Berkshire belonged to Siward Barn, noting the possibility that these estates belonged to Siward of Maldon.[27]

The total value of his holdings is put at 142 libra ("pounds") and 6 solidi ("shillings").[28] Siward Barn ranks 21st out of all the English landowners in the time of King Edward below the rank of earl.[29]

Nothing more is heard of Siward until 1087, the year of the death of William the Conqueror. The Chronicle of John of Worcester relates that:

On his [King William's] return [from France] fierce intestinal pains afflicted him, and he got worse from day to day. When, as his illness worsened, he felt the day of his death approaching, he set free his brother, Odo, bishop of Bayeux, earls Morkar and Roger, Siward called Barn, and Wulfnoth, King Harold's brother (whom he had kept in custody since childhood), as well as all he had kept imprisoned either in England or Normandy. Then he handed the English kingdom over to William [Rufus], and granted the Norman duchy to Robert [Curthose], who was then exiled in France. In this way, fortified by the holy viaticum, he abandoned both life and kingdom on Thursday, 9 September, after ruling the English kingdom for twenty years, ten months, and twenty-eight days.[30]

A similar account is in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, recension E, though specific names are omitted.[31] This unfortunately is also the last notice of Siward in any near-contemporary, reliable source.[32]

Varangian and colonist?

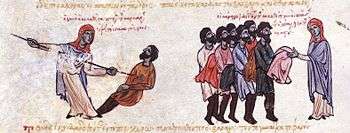

Two modern historians, however, have argued that Siward subsequently became a mercenary in the service of the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos.[33] A 13th-century French chronicle known as the Chronicon Laudunensis (or Chronicon universale anonymi Laudunensis, "the anonymous universal chronicle of Laon") and the 14th century Icelandic text, the Játvarðar Saga, a short saga devoted to the life of Edward the Confessor, both relate a story about English warriors who sail to Constantinople to escape the dominion of the Normans, and found a colony in the Black Sea called New England.[34] The Játvarðar Saga says that the leader of this expedition was one "Siward earl of Gloucester" (Sigurð jarl af Glocestr).[35]

Siward and his force were said to have rescued Constantinople from a siege by "heathens", after which the emperor Alexios offered Siward and his men positions in the Varangian Guard.[36] According to both sources, Siward and some of the English expressed their desire to have a territory of their own, and so Alexius told them of a land over the sea that had formerly been part of the empire, but was now occupied by heathens.[37] The emperor subsequently granted this land to the English, and a party led by Earl Siward sailed onwards to take control of it.[37] The land, the sources allege, lay "6 days north and north-east of Constantinople", a distance and direction that puts the territory somewhere in or around the Crimea and Sea of Azov.[38] Earl Siward, after many battles, defeated and drove away the heathens.[39] The Chronicon Laudunensis says that this territory was renamed "New England",[40] while the Játvarðar Saga claims that the towns of the land were named after English towns, including London and York.[39] The Chronicon alleges that, later, the English rebelled against Byzantine authority and became pirates.[40]

The theory that this Siward is Siward Barn was advocated by Jonathan Shepard and Christine Fell.[41] Shepard pointed out, although never called "Earl of Gloucester", Siward had holdings in Gloucestershire – the only substantial Siward in Domesday Book with property in that county[42] — and was indeed a participant in resistance to the Normans.[43] Shepard argued that the narrative in question referred not, as the Chronicon Laudunensis had asserted, to the 1070s, but to the 1090s, after Siward's release from prison.[44] Fell, while acknowledging that there were two Siwards participating in resistance to William the Conqueror, Siward Barn and Siward of Maldon, pointed out that Siward Barn is more prominent in the literary sources and, unlike Siward of Maldon, had property in Gloucestershire.[45] Two other historians who have since commented on the point, John Godfrey and Ann Williams, accepted that the identification is tenuous and remained neutral.[46]

References

- Clarke, English Nobility, pp. 32–3

- Chibnall (ed.), Ecclesiastical History, vol. ii, p. 195

- For some citations, see Chibnall (ed.), Ecclesiastical History, vol. ii, p. 194, n. 4

- Chibnall (ed.), Ecclesiastical History, vol. ii, p. 194–5, n. 4,

- Williams, The English, pp. 8, 89–6, 175–6; she does not call him "Grossus", but this is the nickname used by Clarke, English Nobility, pp. 339–40 et passim

- See, especially, table vi, Williams, The English, p. 91

- Scott, "Earl Waltheof", p. 172

- Faull and Stinson, Domesday Book: Yorkshire, part ii, s.v. "SIGVARTHBARN", page number not marked, but in appendix, section 4 "Biographies of Tenants: English"

- Barrow, "Companions of the Atheling", p. 40

- Green, Aristocracy, p. 102

- Fleming, Kings and Lords, p. 165

- Fleming, Kings and Lords, p. 166; Green, Aristocracy, p. 102

- Fleming, Kings and Lords, p. 166; Green, Aristocracy, p. 103

- Fleming, Kings and Lords, p. 166; Green, Aristocracy, p. 103; Kapelle, Norman Conquest, p. 114

- Fleming, Kings and Lords, p. 166

- Douglas and Greenway (eds.), English Historical Documents, vol. ii, p. 155; Kapelle, Norman Conquest, p. 114

- Chibnall (ed.), Ecclesiastical History, vol. ii, pp. 226–9

- Kapelle, Norman Conquest, p. 119

- Kapelle, Norman Conquest, p. 117

- Green, Aristocracy, pp. 103–4

- Kapelle, Norman Conquest, p. 125; Williams, The English, p. 39

- Arnold (ed.), Opera Omnia, vol. i, p. 195; Stevenson, Simeon of Durham, p. 142

- Douglas and Greenway (eds.), English Historical Documents, vol. ii, p. 159

- Anderson, Scottish Annals, p. 93, n. 2; Green, Aristocracy, pp. 105–6; Williams, The English, pp. 55–7

- Fleming, Kings and Lords, pp. 163, 176, n. 165; Williams and Martin (eds.), Domesday Book, pp. 953–4, 1140

- List and table of property given, Clarke, English Nobility, pp. 338–9

- Williams, The English, p. 34, n. 72

- Clarke, English Nobility, p. 339

- Clarke, English Nobility, p. 38

- McGurk (ed.), The Chronicle of John of Worcester, vol. iii, p. 47

- McGurk (ed.), The Chronicle of John of Worcester, vol. iii, p. 46, n. 7

- Williams, The English, p. 34

- Fell, "Anglo-Saxon Emigration to Byzantium", pp. 184–5; Shepard, "English and Byzantium", pp. 82–3; see also, below

- Ciggaar, "L'Émigration Anglaise", pp. 301–2; Fell, "Anglo-Saxon Emigration to Byzantium", pp. 179–82; Játvarðar Saga is translated in Dasent, Icelandic Sagas, vol. iii, pp. 416–28, reprinted Ciggaar, "L'Émigration Anglaise", pp. 340–2; the relevant portion of the Chronicon Laudunensis is printed in Ciggaar, "L'Émigration Anglaise", pp. 320–3

- Dasent, Icelandic Sagas, vol. iii, pp. 425–6

- Dasent, Icelandic Sagas, vol. iii, pp. 426–7

- Ciggaar, "L'Émigration Anglaise", p. 322; Dasent, Icelandic Sagas, vol. iii, p. 427

- Dasent, Icelandic Sagas, vol. iii, pp. 427–8; see also Ciggaar, "L'Émigration Anglaise", pp. 322–3, and Shepard, "Another New England?", passim

- Dasent, Icelandic Sagas, vol. iii, pp. 427–8

- Ciggaar, "L'Émigration Anglaise", p. 323

- Fell, "Anglo-Saxon Emigration to Byzantium", pp. 184–5; Godfrey, "The Defeated Anglo-Saxons", p. 69; Shepard, "English and Byzantium", pp. 82–3

- See Clarke, English Nobility, pp. 338–42

- Shepard, "English and Byzantium", pp. 82–3

- Shepard, "English and Byzantium", pp. 83–4

- Fell, "Anglo-Saxon Emigration to Byzantium", pp. 184–5

- Godfrey, "The Defeated Anglo-Saxons", p. 69; Williams, The English, p. 34, n. 71

Sources

- Anderson, Alan Orr, ed. (1908), Scottish Annals from English Chroniclers A.D. 500 to 1286 (1991 revised & corrected ed.), Stamford: Paul Watkins, ISBN 1-871615-45-3

- Arnold, Thomas, ed. (1882–85), Symeonis Monachi Opera Omnia, Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores, or, Chronicles and Memorials of Great Britain and Ireland during the Middle Ages; vol. 75 (2 vols.), London: Longman

- Barrow, G. W. S. (2003), "Companions of the Atheling", Anglo-Norman Studies: Proceedings of the Battle Conference [2002], Boydell Press, 25: 35–45, ISBN 0-85115-941-9

- Chibnall, Marjorie (1990), The Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis; Volume II, Books III and IV, Oxford Medieval Texts, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-820220-2

- Ciggaar, Krijnie N. (1974), "L'Émigration Anglaise a Byzance après 1066: Un Nouveau Texte en Latin sur les Varangues à Constantinople", Revue des Études Byzantines, Paris: Institut Français d'Études Byzantines, 32: 301–42, doi:10.3406/rebyz.1974.1489, ISSN 0766-5598

- Clarke, Peter A. (1994), The English Nobility under Edward the Confessor, Oxford Historical Monographs, Oxford: Clarendon Press, ISBN 0-19-820442-6

- Dasent, G. W., ed. (1894), Icelandic Sagas and Other Historical Documents Relating to the Settlements and Descents of the Northmen on the British Isles [4 vols; 1887–94], Rerum Britannicarum Medii Aevi scriptores ; [88], 3, London: Eyre and Spottiswoode

- Douglas, David C.; Greenway, George W., eds. (1981), English Historical Documents. [Vol.2], c.1042–1189 (2nd ed.), London: Eyre Methuen, ISBN 0-413-32500-8

- Faull, Margaret L.; Stinson, Marie, eds. (1986), Domesday Book. 30, Yorkshire [2 vols.], Domesday Book: A Survey of the Counties of England, Chichester: Phillimore, ISBN 0-85033-530-2

- Fell, Christine (1974), "The Icelandic Saga of Edward the Confessor: Its Version of the Anglo-Saxon Emigration to Byzantium", Anglo-Saxon England, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 3: 179–96, doi:10.1017/S0263675100000673

- Fleming, Robin (1991), Kings & Lords in Conquest England, Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought: Fourth Series, volume 15, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-39309-4

- Godfrey, John (1978), "The Defeated Anglo-Saxons Take Service with the Byzantine Emperor", Anglo-Norman Studies: Proceedings of the First Battle Abbey Conference, Ipswich: Boydell Press, 1: 63–74

- Green, Judith (2002), The Aristocracy of Norman England, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-52465-2

- Kapelle, William E. (1979), The Norman Conquest of the North: The Region and Its Transformation, 1000–1135, London: Croom Helm Ltd, ISBN 0-7099-0040-6

- McGurk, P., ed. (1995), The Chronicle of John of Worcester. Volume III, 1067–1140 with the Gloucester Interpolations and the Continuation to 1141, Oxford Medieval Texts, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-820702-6

- Scott, Forrest S. (1952), "Earl Waltheof of Northumbria", Archaeologia Aeliana, Fourth Series, XXX: 149–215, ISSN 0261-3417

- Shepard, Jonathan (1978), "Another New England? — Anglo-Saxon Settlement on the Black Sea", Byzantine Studies, Tempe: Arizona University Press, 1:1: 18–39

- Shepard, Jonathan (1973), "The English and Byzantium: A Study of Their Role in the Byzantine Army in the Later Eleventh Century", Traditio: Studies in Ancient and Medieval History, Thought, and Religion, New York: Fordham University Press, 29: 53–92, doi:10.1017/S0362152900008977, ISSN 0362-1529

- Stevenson, Joseph (1987), Symeon of Durham: A History of the Kings of England, Facsimile reprint of 1987, from Church Historians of England, vol. iii. 2 (1858), Lampeter: Llanerch, ISBN 0-947992-12-X

- Whitelock, Dorothy, ed. (1979), English Historical Documents. [Vol.1], c.500–1042, London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, ISBN 0-19-520101-9

- Williams, Ann; Martin, G. H., eds. (2003), Domesday Book: A Complete Translation, Alecto Historical Editions (Penguin Classics ed.), London: Penguin Books Ltd, ISBN 0-14-143994-7

- Williams, Ann (1995), The English and the Norman Conquest, Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, ISBN 0-85115-588-X