Siphonophorae

Siphonophorae (from Greek siphōn 'tube' + pherein 'to bear'[2]) is an order of Hydrozoans, a class of marine organisms belonging to the phylum Cnidaria. According to the World Register of Marine Species, the order contains 175 species.[3]

| Siphonophorae | |

|---|---|

| |

| (A) Rhizophysa eysenhardtii scale bar = 1 cm, (B) Bathyphysa conifera 2 cm, (C) Hippopodius hippopus 5 mm, (D) Kephyes hiulcus 2 mm (E) Desmophyes haematogaster 5 mm (F) Sphaeronectes christiansonae 2 mm, (G) Praya dubia 4 cm (1.6 in), (H) Apolemia sp. 1 cm, (I) Lychnagalma utricularia 1 cm, (J) Nanomia sp. 1 cm, (K) Physophora hydrostatica 5 mm | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Class: | Hydrozoa |

| Subclass: | Hydroidolina |

| Order: | Siphonophorae Eschscholtz, 1829 |

| Suborders[1] | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Although a siphonophore may appear to be an individual organism, each specimen is in fact a colonial organism composed of medusoid and polypoid zooids that are morphologically and functionally specialized.[4] Zooids are multicellular units that develop from a single fertilized egg and combine to create functional colonies able to reproduce, digest, float, maintain body positioning, and use jet propulsion to move.[5] Most colonies are long, thin, transparent floaters living in the pelagic zone.[6]

Like other hydrozoans, some siphonophores emit light to attract and attack prey. While many sea animals produce blue and green bioluminescence, a siphonophore was only the second life form found to produce a red light (the first one being the scaleless dragonfish Chirostomias pliopterus).[7]

Anatomy and morphology

Colony characteristics

Siphonophores are colonial hydrozoans that reproduce asexually through a budding process.[6] Zooids are the multicellular units that build the colonies. A single bud called the pro-bud initiates the growth of a colony by undergoing fission.[6] Each zooid is produced to be genetically identical; however, mutations can alter their functions and increase diversity of the zooids within the colony.[6] Siphonophores are unique in that the pro-bud initiates the production of diverse zooids with specific functions.[6] The functions and organizations of the zooids in colonies widely vary among the different species; however, the majority of colonies are bilaterally arranged with dorsal and ventral sides to the stem.[6] The stem is the vertical branch in the center of the colony to which the zooids attach.[6] Zooids typically have special functions, and thus assume specific spatial patterns along the stem.[6]

General morphology

Siphonophores typically exhibit one of the three standard body plans. The body plans are named Cystonecta, Physonecta, and Calycophorae.[8] Cystonects have a long stem with the attached zooids.[8] Each group of zooids has a gastrozooid.[8] The gastrozooid has a tentacle used for capturing and digesting food.[8] The groups also have gonophores, which are specialized for reproduction.[8] They use a pneumatophore, a gas-filled float, on their anterior end and mainly drift at the surface of the water.[8] Physonects have a pneumatophore and nectosome, which harbors the nectophores used for jet propulsion.[8] The nectophores pump the water back in order to move forward.[8] Calycophorans differ from cystonects and physonects in that they have two nectophores and no pneumatophore.[8]

- Zooids

- Siphonophores can have zooids that are either polyps or medusae.[9] However, zooids are unique and can develop to have different functions.[9]

- Nectophores

- Nectophores are medusae that assist in the propulsion and movement of some siphonophores in water.[5] They are characteristic in physonectae and calycophores. The nectophores of these organisms are located in the nectosome where they can coordinate the swimming of colonies.[5] The nectophores have also been observed in working in conjunction with reproductive structures in order to provide propulsion during colony detachment.[5]

- Bracts

- Bracts are zooids that are unique to the siphonophorae order. They function in protection and maintaining a neutral buoyancy.[5] However, bracts are not present in all species of siphonophore.[5]

- Gastrozooids

- Gastrozooids are polyps that have evolved a function to assist in the feeding of siphonophores.[10]

- Palpons

- Palpons are modified gastrozooids that function in digestion by regulating the circulation of gastrovascular fluids.[5]

- Gonophores

- Gonophores are zooids that are involved in the reproductive processes of the siphonophores.[5]

- Pneumatophores

- The presence of pneumatophores characterizes the subgroups Cystonectae and Physonectae.[11] They are gas-filled floats that are located at the anterior end of the colonies in these species.[5] They function to help the colonies maintain their orientation in water.[5] In the cystonectae subgroup, the pneumatophores have an additional function of assisting with flotation of the organisms.[5] The siphonophores exhibiting the feature develop the structure in early larval development via invaginations of the flattened planula structure. [5] Further observations of the siphonophore species Nanomia bijuga indicate that the pneumatophore feature potentially also functions to sense pressure changes and regulate chemotaxis in some species.[12]

Distribution and habitat

Currently, the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) identifies 175 species of siphonophores.[8] They can differ greatly in terms of size and shape, which largely reflects the environment that they inhabit.[8] Siphonophores are most often pelagic organisms, yet level species are benthic.[8] Smaller, warm-water siphonophores typically live in the epipelagic zone and use their tentacles to capture zooplankton and copepods.[8] Larger siphonophores live in deeper waters, as they are generally longer and more fragile and must avoid strong currents.[8] The majority of siphonophores live in the deep sea and can be found in all of the oceans.[8] Siphonophore species rarely only inhabit one location.[8] Some species, however, can be confined to a specific range of depths and/or an area of the ocean.[8]

Behavior

Predation and feeding

Siphonophores are predatory carnivores.[4] Their diets consist of a variety of copepods, small crustaceans, and small fish.[4] A majority of siphonophores have gastrozooids that have a characteristic tentacle attached to the base of the zooid.[5] This structural feature functions in assisting the organisms in catching prey. Similar to many other organisms in the phylum of Cnidaria, many siphonophore species exhibit nematocyst stinging capsules on branches of their tentacles called tentilla.[5] The nematocysts are arranged in dense batteries on the side of the tentilla.[5] When the siphonophore encounters potential prey, they utilize their 30–50 cm (12–20 in) tentacles to create a net around the prey.[4] The nematocysts then shoot paralyzing, and sometimes fatal, toxins at the trapped prey which is then transferred to the proper location for digestion.[4]

Due to the lack of food in the deep sea environment, a majority of siphonophore species function in a sit and wait tactic for food.[13] They swim around waiting for their long tentacles to encounter prey. In addition, siphonophores in a group denoted Erenna have the ability to generate red bioluminescence while its tentilla twitches in a way to mimic motions of small crustaceans and copepods.[7] These actions entice the prey to move closer to the siphonophore, allowing it to trap and digest it.[7]

Reproduction

The modes of reproduction for siphonophores vary among the different species, and to this day, several modes remain unknown. Generally, a single zygote begins the formation of a colony of zooids.[14] The fertilized egg matures into a protozooid, which initiates the budding process and creation of a new zooid.[14] This process repeats until a colony of zooids forms around the central stalk.[14] In contrast, several species reproduce using polyps. Polyps can hold eggs and/or sperm and can be released into the water from the posterior end of the siphonophore.[14] The polyps may then be fertilized outside of the organism.[14]

Siphonophores use gonophores to make the reproductive gametes.[10] Gonophores are either male or female; however, the types of gonophores in a colony can vary among species.[10] Species are characterized as monoecious or dioecious based on their gonophores.[10] Monoecious species contain male and female gonophores in a single zooid colony, whereas dioecious species harbor male and female gonophores separately in different colonies of zooids.[10]

Bioluminescence

Nearly all siphonophores have bioluminescent capabilities. Since these organisms are extremely fragile, they are rarely observed alive.[7] Bioluminescence in siphonophores has been thought to have evolved as a defense mechanism. Siphonophores in the genus Erenna are thought to use their bioluminescent capability as a lure to attract fish.[7] This genus is one of the few to prey on fish rather than crustaceans.[7] The bioluminescent organs on these individuals flicker, and thus it has been concluded that they use bioluminescence to attract prey.[7]

Movement

Siphonophores use a method of locomotion similar to jet propulsion. A nectophore is a gathering of many siphonophores, and depending on where each individual siphonophore is positioned within the nectophore, their function differs.[15] Colonial movement is determined by individual siphonophores of all developmental stages. The smaller individuals are concentrated towards the top of the nectophore, and their function is turning and adjusting the orientation of the colony.[15] The smaller the individual, the younger it is. The larger the individual, the older it is. The larger individuals are located at the base of the colony, and their main function is thrust propulsion.[15] These larger individuals are important in attaining the maximum speed of the colony.[15] The colonial organization of siphonophores, particularly in Nanomia bijuga confers evolutionary advantages.[15] A large amount of concentrated individuals allows for redundancy.[15] This means that even if some individual siphonophores become functionally compromised, the colony as a whole is not negatively affected.

Taxonomy

.jpg)

Organisms in the order of Siphonophorae have been classified into the phylum Cnidaria and the class Hydrozoa.[3] The phylogenetic relationships of siphonophores have been of great interest due to the high variability of the organization of their polyp colonies and medusae.[16][10] Once believed to be a highly distinct group, larval similarities and morphological features have led researchers to believe that siphonophores had evolved from simpler colonial hydrozoans similar to those in the orders Anthoathecata and Leptothecata.[11] Consequently, they are now united with these in the subclass Hydroidolina.

Early analysis divided siphonophores into 3 main subgroups based on the presence or the absence of 2 different traits: swimming bells (nectophores) and floats (pneumatophores).[11] The subgroups consisted of Cystonectae, Physonectae, and Calycorphores. Cystonectae had pneumatophores, physonectae had nectophores, and calycophores had both.[11]

Eukaryotic nuclear small subunit ribosomal gene 18S, eukaryotic mitochondrial large subunit ribosomal gene 16S, and transcriptome analyses further support the phylogenetic division of Siphonophorae into 2 main clades: Cystonectae and Codonophora. Suborders within Codonophora include Physonectae (consisting of the clades Calycophorae and Euphysonectae), Pyrostephidae, and Apolemiidae.[5][10]

- Suborder Calycophorae

- Abylidae Agassiz, 1862

- Clausophyidae Totton, 1965

- Diphyidae Quoy & Gaimard, 1827

- Hippopodiidae Kölliker, 1853

- Prayidae Kölliker, 1853

- Sphaeronectidae Huxley, 1859

- Tottonophyidae Pugh, Dunn & Haddock, 2018

- Suborder Cystonectae

- Physaliidae Brandt, 1835

- Rhizophysidae Brandt, 1835

- Suborder Physonectae

- Agalmatidae Brandt, 1834

- Apolemiidae Huxley, 1859

- Cordagalmatidae Pugh, 2016

- Erennidae Pugh, 2001

- Forskaliidae Haeckel, 1888

- Physophoridae Eschscholtz, 1829

- Pyrostephidae Moser, 1925

- Resomiidae Pugh, 2006

- Rhodaliidae Haeckel, 1888

- Stephanomiidae Huxley, 1859

History

Discovery

Carl Linnaeus discovered and described the first siphonophore, the Portuguese man o' war, in 1758.[8] The discovery rate of siphonophore species was slow in the 18th century, as only four additional species were found.[8] During the 19th century, 56 new species were observed due to research voyages conducted by European powers.[8] The majority of new species found during this time period were collected in coastal, surface waters.[8] During the HMS Challenger expedition, various species of siphonophores were collected. Ernst Haeckel attempted to conduct a write up of all of the species of siphonophores collected on this expedition. He introduced 46 "new species"; however, his work was heavily critiqued because some of the species that he identified were eventually found not to be siphonophores.[8] Nonetheless, some of his descriptions and figures (pictured below) are considered useful by modern biologists. A rate of about 10 new species discoveries per decade was observed during the 20th century.[8] Considered the most important researcher of siphonophores, A. K. Totton introduced 23 new species of siphonophores during the mid 20th century.[8]

On April 6, 2020 the Schmidt Ocean Institute announced the discovery of a giant Apolemia siphonophore in submarine canyons near Ningaloo Coast, measuring 15 m (49 ft) diameter with a ring approximately 47 m (154 ft) long, possibly the largest siphonophore ever recorded.[17][18]

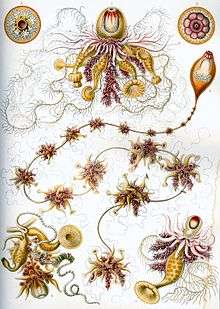

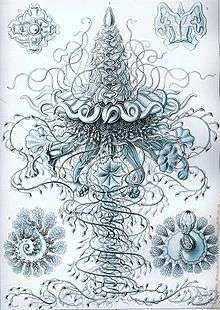

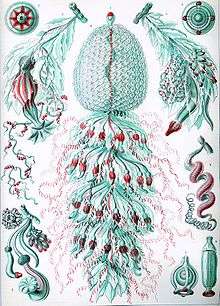

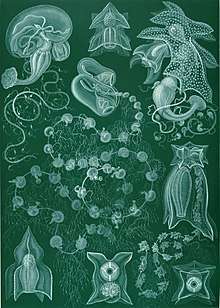

Haeckel's siphonophores

Ernst Haeckel described a number of siphonophores, and several plates from his Kunstformen der Natur (1904) depict members of the taxon:[19]

Plate 7

Plate 7 Plate 37

Plate 37 Plate 59

Plate 59 Plate 77

Plate 77

References

- Schuchert, P. (2019). "Siphonophorae". World Hydrozoa Database. Retrieved 2019-01-27 – via World Register of Marine Species.

- "Siphonophora". Lexico. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- "Siphonophorae". World Register of Marine Species (2018). Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- Pacific, Aquarium of the. "Pelagic Siphonophore". www.aquariumofpacific.org. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- Munro, Catriona; Siebert, Stefan; Zapata, Felipe; Howison, Mark; Damian Serrano, Alejandro; Church, Samuel H.; Goetz, Freya E.; Pugh, Philip R.; Haddock, Steven H.D.; Dunn, Casey W. (2018-01-20). "Improved phylogenetic resolution within Siphonophora (Cnidaria) with implications for trait evolution". doi:10.1101/251116. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Dunn, Casey W. (December 2005). "Complex colony-level organization of the deep-sea siphonophore Bargmannia elongata (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa) is directionally asymmetric and arises by the subdivision of pro-buds". Developmental Dynamics. 234 (4): 835–845. doi:10.1002/dvdy.20483. PMID 15986453.

- Haddock SH, Dunn CW, Pugh PR, Schnitzler CE (July 2005). "Bioluminescent and red-fluorescent lures in a deep-sea siphonophore". Science. 309 (5732): 263. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.384.7904. doi:10.1126/science.1110441. PMID 16002609. S2CID 29284690.

- Mapstone, Gillian M. (2014-02-06). "Global Diversity and Review of Siphonophorae (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa)". PLOS ONE. 9 (2): e87737. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...987737M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087737. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3916360. PMID 24516560.

- Dunn, Casey (2009). "Siphonophores". Current Biology. 19 (6): R233-4. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.009. PMID 19321136. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- Dunn, Casey W.; Pugh, Philip R.; Haddock, Steven H. D. (2005-12-01). Naylor, Gavin (ed.). "Molecular Phylogenetics of the Siphonophora (Cnidaria), with Implications for the Evolution of Functional Specialization". Systematic Biology. 54 (6): 916–935. doi:10.1080/10635150500354837. ISSN 1076-836X. PMID 16338764.

- Collins, Allen G. (30 April 2002). "Phylogeny of Medusozoa and the evolution of cnidarian life cycles". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 15 (3): 418–432. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00403.x.

- Church, Samuel H.; Siebert, Stefan; Bhattacharyya, Pathikrit; Dunn, Casey W. (July 2015). "The histology of Nanomia bijuga (Hydrozoa: Siphonophora)". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 324 (5): 435–449. doi:10.1002/jez.b.22629. PMC 5032985. PMID 26036693.

- Dunn, Casey (2005). "Siphonophores". Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- Pacific, Aquarium of the. "Pelagic Siphonophore". www.aquariumofpacific.org. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- Costello, John H.; Colin, Sean P.; Gemmell, Brad J.; Dabiri, John O.; Sutherland, Kelly R. (November 2015). "Multi-jet propulsion organized by clonal development in a colonial siphonophore". Nature Communications. 6 (1): 8158. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.8158C. doi:10.1038/ncomms9158. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4569723. PMID 26327286.

- Waggoner, Ben (July 21, 1995). "Hydrozoa: More on Morphology". UC Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- "Longest Giant Stringy Sea Creature Ever Recorded Looks like It Belongs in Outer Space". interestingengineering.com. 2020-04-09. Retrieved 2020-04-10.

- Schmidt Ocean Institute (9 April 2020). "New species discovered during exploration of abyssal deep sea canyons off Ningaloo". EurekAlert!. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- Costantino, Grace. "Art Forms in Nature: Marine Species From Ernst Haeckel". Smithsonian Ocean. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

Further reading

- Mapstone, Gillian M. (2009). Siphonophora (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa) of Canadian Pacific waters. Ottawa: NRC Research Press. ISBN 978-0-660-19843-9.

- PinkTentacle.com (2008): Siphonophore: Deep-sea superorganism (video). Retrieved 2009-MAY-23.

External links

- Dunn, Casey (n.d.). "Siphonophores". Current Biology. n/a. 19 (6): R233-4. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.009. PMID 19321136. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- Scubamedia.de (30 August 2013). "Tauchen in Norwegen - Kvasefjord". YouTube. scubamedia.de. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- Pinktentacle3 (22 December 2008). "Siphonophore". YouTube. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- "Stunning Siphonophore Sighting". Nautilus Live: Explore the ocean LIVE with Dr. Robert Ballard and the Corps of Exploration. Ocean Exploration Trust. 27 June 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ''Deep sea siphonophore'' (10 April 2017) YouTube. Imaged by the NOAA Okeanos Explorer on March 14, 2017 at 1,560 meters west of Winslow Reef complex. Retrieved 28 January 2018.